In 1965, a young woman lived in isolation with a male dolphin in the name of science. It got weird

Week 5 of Margaret Howe’s diary is concerned with a new issue: Peter's 'sexual needs' are frustrating research. She decides to take matters into her own hands

You can save this article by registering for free here . Or sign-in if you have an account.

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

Article content

From outside it looked like another spacious Virgin Islands villa with a spiral staircase twisting up to a sunny balcony overlooking the Caribbean Sea. But Dolphin Point Laboratory on the island of St Thomas was part of a unique Washington-funded research institute run by Dr John C Lilly, the wackiest and most polarizing figure in marine science history. A medic and neurologist by training, a mystic by inclination, he was intent on furthering his investigations into the communication skills of dolphins, who he believed could help us talk to extraterrestrials.

For 10 weeks, from June to August 1965, the St Thomas research centre became the site of Lilly’s most notorious and highly criticized experiment, when his young assistant, Margaret Howe, volunteered to live in confinement with Peter, a bottlenose dolphin. The dolphin house was flooded with water and redesigned for a specific purpose: to allow the 23-year-old Howe and the dolphin to live, sleep, eat, wash and play intimately together. The objective of the experiment was to see whether a dolphin could be taught human speech – a hypothesis that Lilly, in 1960, predicted could be a reality “within a decade or two.”

In 1965, a young woman lived in isolation with a male dolphin in the name of science. It got weird Back to video

Enjoy the latest local, national and international news.

- Exclusive articles by Conrad Black, Barbara Kay and others. Plus, special edition NP Platformed and First Reading newsletters and virtual events.

- Unlimited online access to National Post and 15 news sites with one account.

- National Post ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Don't have an account? Create Account

Even dolphin experts who today hold some of Lilly’s other work in high regard believe it was deeply misguided. Media coverage at the time focused on two things: Howe’s almost total failure to teach Peter to speak; and the reluctant sexual relationship she began with the animal in an effort to put him at his ease. She has not spoken about her experiences for nearly 50 years (to “let [the story] fade”), but earlier this year accepted an interview request by the BBC producer Mark Hedgecoe, who thought it was “the most remarkable story of animal science I had ever heard.”

The result, a documentary called The Girl Who Talked to Dolphins, is set to premiere at Sheffield Doc/Fest and then on BBC Four later in June. Various films and documentaries have dissected some of the baffling, entertaining and ultimately tragic animal-human language experiments offered up by the Sixties and Seventies, most recently James Marsh’s 2011 feature Project Nim, about a chimp raised in a New York family. But what makes the dolphin house story unique is the intensity of the period of interspecies cohabitation. Howe and Peter lived in complete isolation.

Prof Thomas White, a philosopher and international leader in the field of dolphin ethics, believes the experiment was “cruel” and flawed from the outset. “Lilly was a pioneer,” he says. “Not just in the study of the dolphin brain; he was an open-minded scientist who speculated very early on that dolphins are self-aware creatures with emotional vulnerabilities that need an array of relationships to flourish. That should have made him think: ’I really shouldn’t be doing this kind of thing’?”

Lilly, who had gained the scientific establishment’s respect with his work on the human brain, became interested in dolphins in the Fifties, after performing a series of “inner-consciousness” investigations on himself in which he floated around for hours in salt water in an effort to block outside stimuli and increase his sensitivity.

His 1961 book Man and Dolphin was an international bestseller. It was the first book to claim that dolphins displayed complex emotions – that they were capable of controlling anger, for example, and that they, like humans, often trembled in response to being hurt. Some dolphin species, he said, had brains up to 40% larger than humans’. As well as being our “cognitive equal,” Lilly speculated they were capable of a form of telepathy that was the key to understanding extraterrestrial communication. He also believed they could “teach us to live in outer space without gravity”. He also proposed that they could be trained to serve the Navy as a “glorified seeing-eye” (a theory that became the basis of the 1973 sci-fi thriller Day of the Dolphin, despite Lilly’s best attempts to halt production).

If you want to do your experiments on solitude and LSD, please keep them in the isolation room. I am not curious or interested

But Lilly did little to burnish his credentials in the early Sixties when he started exploring the psychological research possibilities offered by lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). He took it himself, often while floating in his isolation tank. Lilly later pinpointed 1965, the year of the dolphin cohabitation experiment, as the year he came to “no longer regard the scientific viewpoint of total objectivity as the be-all and end-all.” It wouldn’t be wildly speculative to suggest that Lilly was – by today’s standards at least – not in quite the right frame of mind to be leading the dolphin project.

Looking back at his memories of the mid-Sixties in his autobiography, an impressionistic account in which he writes of himself in the third person (“He felt that he was merely a small microbe on a mudball, rotating around a G-star, two thirds of the way from Galactic centre…”), it is also apparent how removed he was from Howe’s work.

He writes: “In the midst of his enthusiasm he [Lilly] attempted to speak to [Howe] of his experiences.” Howe, in her early 20s, was not sympathetic. “If you want to do your experiments on solitude and LSD, please keep them in the isolation room. I am not curious or interested.”

Howe was among many keen young staff members he employed from the island. Only the bravest stayed with him any significant length of time; as Lilly noted in The Mind of the Dolphin (1967), the Tursiops (bottlenose) – chosen for study because its brain size was comparable to man’s – was larger and more powerful than most humans. They grew irritable and angry when mismanaged. Howe’s talent for communicating with the dolphins was exceptional and, as Lilly noted, her dedication was unmatched by anyone else in the faculty. “I will not interfere with that,” he wrote.

Still, he prepared the experiment. Following a week-long trial period, Lilly decided 10 weeks was the maximum time frame that both human and dolphin could survive comfortably in confinement. Objectives, regulations and a daily timetable were clear and precise. Howe’s aims were threefold: to make notes on interspecies isolation, to attempt to teach Peter to “speak,” and to gather information so that the living conditions might be improved for longer-term cohabitation.

Cooking is fine. Cleaning is interesting… Each morning most of the dirt is neatly deposited at the foot of the elevator shaft. All I have to do is suck it up

On June 15 Howe moved in, her hair cut to a quarter-inch boy crop. All she needed was a swimming costume and a leotard for the cooler nights. The entire upstairs of the lab building and the balcony had been flooded with salt water 18in deep, which Peter could swim around in and Howe could wade through. A desk hung from the ceiling, and her bed was a suspended foam mattress that she later fitted with a shower curtain so that Peter’s splashes did not soak her through the night. She would live off canned food to minimise contact with outsiders.

“It was perfect,” she remembers today of her domestic dolphinarium. Early entries in her diary at the time reveal that, like a nervous new housewife, she made the best of things: “Cooking is fine. Cleaning is interesting… Each morning most of the dirt is neatly deposited at the foot of the elevator shaft. All I have to do is suck it up.” As for her companion, he spent “a good deal of his time in front of the mirror,” she noted. She was amused to find that during rare moments of contact with the outside world (mostly on the telephone) Peter talked “very loudly and in a competitive way” over the top of her.

Although he could be rambunctious, the archive footage of his lessons featured in the new BBC documentary reveal Peter to have been a curious, dedicated student. Lilly’s team had already established that dolphins could adjust the frequency of their squeaks and whistles to mimic human sounds, and claimed that during his time with Howe, Peter learnt to pronounce words such as “ball” and “diamond”, and to tell the difference between certain objects.

Howe was a creative, commendably patient teacher; when Peter struggled with certain sounds, particularly the “M” in her name, she came up with the inventive method of painting her face in thick white make-up and black lipstick so that he could clearly see the shape of her lips moving. “His eye was in [the] air looking at my mouth. There was no question… He really wanted to know: where is that noise coming from? What is the sound?” she remembers. “Eventually he kind of rolled over so that he would bubble [the ’M’ sound] into the water.”

To those who lived and worked with Peter, his progress was perhaps clearer than it was to the outsider. The average viewer, on watching the BBC documentary, might conclude that the experiment was a failure. Kenneth Norris, an influential marine biologist, said of Lilly: “He started out as a capable scientist, but nothing he did was subject to measurement or truth, and that’s what scientists live by.” Experiments since 1965 have proved that dolphins have high levels of self-awareness and can understand human sign communication – but there is still little evidence that a dolphin language exists.

Peter begins having erections and has them frequently when I play with him

However, Peter’s linguistic progress was seemingly what kept Howe going when their relationship grew strained. Fed up and clearly exhausted by week three, she wrote at length about Peter whining and making loud noises night and day for no apparent reason: “I will do anything to break this… I lost my temper and nearly yelled at Peter… I am physically so pooped I can hardly stand… depression… wanting to get away… my mind is not all on the job.”

Lilly, responding to Howe’s feedback, recorded his concerns. “This is a dull and small area… Isolation effects showing,” he wrote. Howe’s diary of week five is predominantly concerned with a new issue: “Peter begins having erections and has them frequently when I play with him.” Her frustrated efforts to deal with his “sexual needs” and advances – which had become so aggressive that her legs were covered in minor injuries from his jamming and nibbling – had left her scared. “Peter could bite me in two,” she wrote. But she was reluctant to hamper progress, and, in a spirit of pragmatism, decided to take matters into her own hands. As the narrator in the documentary tactfully puts it: “Margaret felt that the best way of focusing his mind back on his lessons was to relieve his desires herself manually.”

Sex among dolphins is a “normal way to establish a bond”, White says. “Dolphins are mostly bisexual, sometimes heterosexual, sometimes homosexual, and quite frequent – eight to 10 times a day I’ve been told – so it’s a very different culture that we’re looking at.” Peter’s sexual advances wouldn’t surprise any marine biologist. But what astonished Lilly was the complexity of the way Peter and Howe’s relationship developed from thereon in.

“New totally unexpected sequence of events took place,” Lilly noted excitedly. “I feel that we are in the midst of a new becoming; moving into a previous unknown…” As Peter became increasingly gentle, tactile and sensitive to Howe’s feelings he began to “woo” her by softly stroking his teeth up and down her legs. “I stand very still, legs slightly apart, and Peter slides his mouth gently over my shin,” she wrote in her diary. “Peter is courting me… he has been most persistent and patient… Obviously a sexy business… The mood is very gentle, still and hushed… all movements are slow.” Today she talks about the whole experience philosophically: “It was very precious. It was very gentle… It was sexual on his part. It was not sexual on mine. Sensual, perhaps.”

Howe’s writing also reflects her increasingly protective feelings towards Peter, and at the end of her diary she admits that Peter’s attentiveness helped her overcome her “depression” and “fits of self-pity.”

It was great [Howe] wasn’t going to be damaged… but as a veterinarian, I wondered about poor Peter. This dolphin was madly in love with her

In a neat romantic twist, it all ended happily for Howe. She left the lab to marry the project’s photographer, John Lovatt. Though dismayed to lose her, even Lilly was pleased: “Her intraspecies needs are finally being taken care of.” She never returned to work for him. Soon after the experiment, Lilly’s funding began to dry up, and with his second marriage in tatters he left to explore mystical interests in South America.

As for Peter, the lab’s vet Andy Williamson remembers his concerns as the experiment came to a close: “It was great [Howe] wasn’t going to be damaged… but as a veterinarian, I wondered about poor Peter. This dolphin was madly in love with her.”

The unexpected consequences of the experiment highlight one of the persisting problems with the “short-sighted” scientific approach to animal intelligence, says White. “We focus on language as the primary indicator of intelligence. Dolphins, like humans, are very sophisticated emotionally as well as intellectually. From an ethical standpoint, that’s what we should be looking at.”

The Sunday Telegraph

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.

They came to Canada on a holiday and started committing crimes the next day

Trudeau’s taking you all down with him: full comment podcast, more than 50 liberal mps leave call with 'consensus' justin trudeau should step down: cbc, raymond j. de souza: jews are the chosen people, deal with it, b.c. mayor gets calls from across canada about 'crazy' plan to recruit doctors, makeup tutorial: a soft, neutral approach delivers understated elegance.

This makeup style offers a sophisticated and effortless application.

Advertisement 2 Story continues below This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Top three ski resorts in Canada

Whether you’re seeking epic terrain, family fun or underexplored hills

The best early Boxing Day deals in Canada 2024

Reformation, Silk & Snow, Sephora and Best Buy, to name a few

Pixel Watch 3 review: Fitter, happier and more productive

Key improvements have made Google’s latest smartwatch an excellent option for Android users

Amazon releases early Boxing Day deals: Our favourites

Take advantage of early deals on tech, home goods and more

This website uses cookies to personalize your content (including ads), and allows us to analyze our traffic. Read more about cookies here . By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy .

You've reached the 20 article limit.

You can manage saved articles in your account.

and save up to 100 articles!

Looks like you've reached your saved article limit!

You can manage your saved articles in your account and clicking the X located at the bottom right of the article.

Margaret Howe Lovatt: The Woman Who Fell in Love with a Dolphin

Many of us know all too well what it’s like to love an animal. We’re often willing to go to great lengths to care for our pets. The close bonds that result can be as strong as any. But how far can they be taken? Enter Margaret Howe Lovatt.

Lovatt is best known for being involved in a controversial experiment in the 1960s. In this research project, she attempted to teach a dolphin named Peter to speak English. It is considered to be one of the most fascinating and controversial stories of its kind.

Lovatt’s attempt to teach the animal led to some insights into dolphin behavior and communication. But it also raised questions about the ethics of animal experimentation and the limits of such relationships.

As Lovatt developed a close bond with Peter, their relationship gradually progressed, even becoming sexual. Some reports suggest that she even fell in love with him.

Altogether, the story of Margaret Howe Lovatt and the Dolphinarium experiment is a captivating, thought-provoking tale. It is every bit as riveting and scandalous as it sounds.

The Dolphinarium Experiment

In the middle of the 1960s, fascinating research was underway. This was during the tumult of the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement, on the tiny Caribbean Island of St. Thomas.

Lovatt, a naturalist, was living on the island. She was volunteering at a laboratory doing research with dolphins. There, she met John C. Lilly, a neuroscientist. He happened to be working with NASA and the U.S. Navy and was building a “Dolphinarium.”

The Dolphinarium experiment was a controversial project that aimed to teach dolphins the human language, specifically English. It was an incredible, extraordinary idea, but the researchers involved believe it to be worth a try.

Margaret Howe Lovatt was assigned to live with and train the dolphins in the facility. She believed that living with the dolphins and making human-like sounds would help in mimicking human language.

Throughout her research, she spent most of her time with a male bottlenose dolphin named Peter. However, their relationship gradually progressed beyond just a typical animal-human friendship.

Margaret’s Teaching Methods and Her Relationship with Peter

Lovatt’s teaching methods were initially fairly straightforward. They were only slightly out of the ordinary.

She lived by the dolphins and spoke to them often. The theory was that similar to a child copying their mother, they would be able to teach the dolphins something about how to speak English.

Lovatt grew closest to Peter. He was a young, but mature, male dolphin at the Dolphinarium. She spent almost two years with him.

Lovatt worked closely with the young dolphin. She documented Peter’s progress twice a day. She spoke slowly and alternated her tone to attempt to get Peter to recreate the words and sounds she wanted him to learn, like “Hello Margaret.”

According to Lovatt, the “m” sound was particularly challenging. But it seems progress was made in other areas.

However, Peter was a sexually maturing adolescent dolphin, and as such he often had sexual urges. This presented certain challenges. As Lovatt and Peter spent more time together in the isolated Dolphinarium, they continued to grow closer, with Lovatt even hinting that Peter liked to be close to her.

Before long, the male dolphin made advances. He rubbed himself on her and disrupted their lessons.

It wasn’t enough to just separate the two when these urges arose. It began to hinder the research completely. To “fix” this, Lovatt did what some might consider unthinkable. When Peter became aroused, Lovatt would “relieve” the dolphin herself in what many considered to be a legitimate sexual act.

Of course, Lovatt saw this as part of her work and even felt that this was something that deepened their close bond. But she refused to consider the behavior as sexual. In the end, many did not see things the same way.

Ethical Concerns and Controversy

Word got out about the nature of Lovatt’s relationship with Peter. The whole situation quickly became a source of controversy and there were allegations of animal abuse.

It was also rumored that Lovatt had injected him with LSD. This added to the uproar. This was largely a conflation with other, separate research.

Still, the relationship between Margaret Howe Lovatt and Peter the dolphin is often cited as an example of the ethical issues surrounding animal experimentation. While Lovatt intended to teach Peter to speak, their relationship gradually became more intimate. The lines between research and personal attachment became blurred.

The allegations raised important questions – and fiery debates – about the ethical boundaries of human-animal relationships. Were Lovatt’s actions abuse? They were surely disturbing and unthinkable to many. But did the specifics of their relationship amount to any real wrongdoing?

For her part, Lovatt denied any wrongdoing and maintained that her relationship with Peter was purely scientific. Though the controversy surrounding the experiment had lasting implications.

Despite the uproar, Lovatt maintained her relationship with Peter. Their relationship went from needing to be together for research, to a relationship of actually enjoying and missing each other when they were apart. Due to an eventual lack of funding for the Dolphinarium, their time together came to an end. The pair split up and Peter was sent to a new home in Miami.

Tragically, Peter the dolphin would commit suicide not long after. Some believe it was the heartbreak of being separated from Lovat. Whereas others cite the small tank and inhumane conditions of his new home.

Media Coverage and Scientific Impact

The ordeal drew widespread media attention. It continues to be a topic of interest and debate today. After an article on Lovatt’s sexual relationship with Peter appeared in the popular magazine, Hustler , the research was largely frowned upon publicly.

Scientifically, little was achieved in the way of teaching dolphins to speak English. However, it does seem that these efforts are still ongoing today in other research labs.

The scientific community largely responded negatively. They raised concerns about behavioral ethics and the potential impact on the well-being of Peter. The controversy surrounding the experiment and Lovatt’s relationship with Peter overshadowed much of the science being done.

Today, Lovatt’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the boundaries of our relationships with animals and the importance of ethical considerations in all manners of scientific research.

Mosendz, Polly. “How a Science Experiment Led to Sexual Encounters between a Woman and a Dolphin.” The Atlantic, June 11, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/06/how-a-science-experiment-led-to-sexual-encounters-for-a-woman-and-a-dolphin/372606/ .

Riley, Christopher. “The Dolphin Who Loved Me: The NASA-Funded Project That Went Wrong.” The Guardian, June 8, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/08/the-dolphin-who-loved-me .

Winfrey, Tiffany. “Woman Admits Having Sexual Experience with Dolphin as Part of NASA Study in the 1960s.” The Science Times, November 7, 2022. https://www.sciencetimes.com/articles/40844/20221107/woman-admits-having-sexual-experience-with-dolphin-as-part-of-nasa-study-in-the-1960s.htm.

Related Posts

The Tragic Lives of Joseph Stalin’s Children

How Sargon of Akkad Created the World’s First Empire

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright and DMCA Notice

Margaret Howe Lovatt: Dolphins, LSD and a Lot More

Research is a broad church. Anything from peer-reviewed, scientifically-rigorous papers to the results of 5 minutes spent Googling has been called research, but even from these two examples it is clear that not all research is equal.

Some research is strict, with clear limitations and goals and a framework in which to couch the findings. And then there is the sort of research Margaret Howe Lovatt was involved in, which led to a sensationalized article by Hustler magazine stating that Margaret had intercourse with the dolphin .

What was this experiment, and what is the truth?

Margaret Howe Lovatt

Margaret Howe Lovatt was living on the island of St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands in her early 20s when, in December 1963, her brother-in-law told her about a secret laboratory on the island’s eastern end that was working with dolphins. She was curious, and in January 1964, she drove to the lab to learn more, or just really to poke around.

At the lab, Margaret ran into Gregory Bateson, a British anthropologist, cyberneticist, linguist, social scientist, visual anthropologist, and semiotician. Baeston is perhaps best known for developing the double-bind theory of schizophrenia .

When Bateson questioned why she was there, Margaret Howe Lovatt told him, “I heard you had dolphins, and I thought I’d come and see if there was anything I could do or any way I could help…” Taken with her bravado and desire to work, she was invited to meet the three dolphins at the lab; Pamela, Sissy, and Peter.

Margaret Howe Lovatt was told to sit and watch the dolphins and record their behavior. With no scientific experience, Lovatt observed and took notes that were good enough for Bateson to tell her to return whenever she wanted.

The lab had been designed by American neuroscientist Dr. John Lilly with the hopes of communicating with the animals and fostering their ability to make “human-like sounds through their blow holes.” They were, pretty much literally, teaching dolphins to speak like a person.

Dr. Lilly and his assistant would “talk” to the dolphins. The dolphins would respond by making a “wuh wuh sound” like Dr. Lilly was making, and the animals also imitated his assistant’s higher voice.

Dolphin-to-Human Communication

Dr. Lilly thought the behavior was a sign that the dolphins wanted to communicate with humans. Dr. Lilly published a book explaining his theory in 1961, Man and Dolphin .

- Military Marine Mammals: A History of Exploding Dolphins

- The Montauk Project and the Outer Limits of US Classified Research

The book expanded on the dolphins mimicking human sounds and that an attempt to teach them to speak English should be made. He also said that teaching dolphins English would lead to “a Cetacean Chair at the United Nations, where all marine mammals would have an enlightened input into world affairs, widening human perspectives on everything from science to history, economics, and current affairs.” The crazy idea was turned into the NASA -funded lab, the same one that Margaret Howe Lovatt visited a year after it had been constructed.

Margaret Howe Lovatt spent as much time as possible with the dolphins, attempting to create a bond and going through a series of daily lessons that were believed to encourage the animals to make human sounds. Gregory Bateson was also working on experiments related to animal-to-animal communication, so Margaret was heavily involved in Dr. Lilly’s strange experiment .

At the end of the day, the humans would leave the facility and go home. Margaret Howe Lovatt felt that if she could live with the dolphins, she could increase their interest in human sounds, much like a mom teaches her baby their first words.

Dr. Lilly loved Margaret’s idea of living with the animals, so he created a bed on the lab’s elevator platform in the middle of the room and hung a desk from the ceiling over the water so Margaret could do paperwork.

During a three-month cohabitation experiment, Margaret Howe Lovatt selected Peter the Dolphin as her subject. Peter had yet to engage in human sound training, unlike Pamela and Sissy.

The plan was that Margaret and Peter would live in isolation six days a week, and on the seventh day, Peter would be returned to the tank with the other two dolphins. Peter was a sexually maturing young dolphin and, at times, would become aroused.

Peter bonded with Margaret, and she said he would “rub himself” on her knee, foot, or hand. When Peter became aroused, he was transferred into the tank with Pamela and Sissy, who were females. Like teen boys during puberty, Peter was distracted by his arousal, and moving him to and from the tank with the girls further distracted him.

In her mind, Margaret Howe Lovatt felt that minimizing distraction was necessary and chose to relieve Peter’s “urges” manually. So, she did what she thought was the most appropriate thing to do in such a situation: she started manually masturbating the dolphin.

Before the red flag of bestiality goes up in your mind, it is essential to note that Margaret never engaged in sex with Peter in a way humans engage in intercourse. She said it didn’t bother her, and getting it over with meant they could return to their lessons.

Her stimulating Peter when he was aroused was not something she did in private or was a secret; anyone at the lab could watch her interact with Peter. It sounds questionable, but Margaret said that this behavior wasn’t sexual on her part, and she did not have an interest in engaging in zoophilia, a paraphilia where a person is sexually fixated on non-human animals.

- A Mighty Bang: Are We In Danger From Exploding Whales?

- Madness, Despair, and Sabotage: The SEALAB Experiment

Margaret Howe Lovatt’s behavior was not an issue with the scientists at the lab, and it was innocent on her part. However, the public felt a different way.

Hustler magazine published an article in the late 1970s titled “Interspecies Sex: Humans and Dolphin” and an illustration of a woman nude gripping onto the underside of a dolphin. Hustler was in direct competition with Playboy , who dominated the market of porn magazines.

A sensational article featured a quote from Dr. Lilly about how dolphins mate and their erections, along with statements that one woman “claimed to have gotten off approximately 900 times with our furry friends” did just what the publishers intended. Thousands of magazines were sold.

Margaret said it was uncomfortable; the implication that she was engaging in intercourse with a dolphin would make anyone uncomfortable. She said it didn’t bother her. Margaret has said, “[sex] was not the point of it [the experiment], nor the result of it. So I just ignore it.”

Did We Not Mention the LSD?

In a piece of news that will come as no shock to anyone, there were also psychoactive drugs involved. Dr.Lilly was one of the few scientists in the US who were authorized to research the effects of LSD. Dr. Lilly was giving the three dolphins LSD to study the effects, but the dolphins didn’t react at all.

So the dolphins weren’t speaking, they weren’t even enjoying the drugs , and this lack of results ultimately led to a lack of funding. The experiments ended abruptly, and the dolphins were relocated to a facility in Miami, Florida .

Here the story takes an even darker turn. Animals have been used to test LSD and its effects as an antidepressant, as have humans for many years. Sadly Peter, the dolphin, committed suicide once he was in Miami.

In the decades since, many have felt that Margaret Howe Lovatt should be punished for “molesting an animal.” However, as gross as it is, she is not the first nor the last scientist who has had to stimulate their animal subjects manually.

Breeding animals often requires a collection of semen through manual means. Professor of primate sexual psychology at Emory University, Kim Wallen, explains that “masturbation for commerce [in animals] is seen as normal and appropriate, but masturbation where the end point is sexual arousal is not. Sex has an uncanny way of revealing inconsistencies in our thinking.”

Top Image: The dolphin experiments in which Margaret Howe Lovatt was involved were anything but ethical. Source: Corina Daniela Obertas / Adobe Stock.

By Lauren Dillon

Clark-Flory, T. 2014. Human-on-dolphin sex is not really that weird . Salon. Available at: https://www.salon.com/2014/06/14/human_on_dolphin_sex_is_not_really_that_weird/

Taub, B. 2017. Scientists Once Gave LSD To Dolphins In The Hope Of Learning To Communicate With Them . IFLScience. Available at: https://www.iflscience.com/scientists-once-gave-lsd-to-dolphins-in-the-hope-of-learning-to-communicate-with-them-42137

Riley, C. 2014. The dolphin who loved me: the Nasa-funded project that went wrong . The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/08/the-dolphin-who-loved-me

Lauren Dillon

Lauren Dillon is a freelance writer with experience working in museums, historical societies, and archives. She earned her Bachelor’s Degree in Russian & Eastern European Studies in 2017 from Florida State University. She went on to earn her Master’s Degree in Museum Studies in 2019 from the University of San Francisco. She loves history, true crime, mythology, and anything strange and unusual. Her academic background has inspired her to share the parts of history not in most textbooks. She enjoys playing the clarinet, taking ballet classes, textile art, and listening to an unhealthy amount of true crime podcasts. Read More

Related Posts

1882 winchester rifle mystery, shocking myths about the salem witch trials (video), ultra: how did the allied codebreakers crack the..., wenceslao moguel, the man who survived the firing..., how the wardian case helped introduce tea to..., is escape on the cards the hidden maps....

Search for: Search Button

The Dolphin House

Nov 4, 2023 | Nature , Videos

Dolphins are renowned for their intelligence, with many experts believing they are the second smartest creatures on Earth, after humans. The small cetaceans have been the subjects of much scientific research over the last 70 years, with one of the most famous and provocative experiments taking place in 1965. Conducted by eccentric yet renowned neuroscientist John Lilly, he set up a lab called Dolphin House on St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands to explore dolphin communication and learning abilities.

John enlisted 23-year old Margaret Howe to assist him, who lived in the flooded house with a mature bottle-nosed dolphin named Peter for 10 to 12 weeks. During this time, Margaret attempted to teach Peter how to speak English, using techniques akin to those of a mother teaching her toddler. Early researchers had already discovered that dolphins could mimic human tones and seemed to interact with each other in an advanced way; NASA even provided some funding as they hoped any insights gained could be applied to possible communications with extraterrestrial beings.

Things took a turn for the worse when John grew impatient with progress and chose to inject Peter with LSD in order stimulate his brain – something which greatly affected him, making him become more aggressive and even nibbling at Margaret’s feet and legs if he was overly stimulated. Eventually depressed from being drugged and isolated from other dolphins, Peter committed suicide by refusing to come up for air from his tank – an event which caused an uproar among animal rights activists and led to John losing all his funding from NASA and other sponsors.

The Dolphin House experiment was undoubtedly an experiment gone wrong; however it did bring attention to both dolphin intelligence as well as ethical practices when dealing with animals used in experiments or captivity. A documentary about this remarkable experiment has been created titled ‘Dolphin Tale’, based on actual events during this time period. This documentary is a must watch for anyone interested in learning more about dolphin communication as well as marveling at their incredible abilities; it not only brings justice but also respect for these remarkable creatures of our oceans.

Read On – Our Latest Top Documentaries Lists

The 10 best documentaries about the cranberries, the 7 best documentaries about barry white, the 6 best documentaries about william mckinley, the best documentaries about esports, the 11 best documentaries about madrid, the 3 best documentaries about vancouver, the 11 best documentaries about mumbai, the 9 best documentaries about the pretenders, the 11 best documentaries about usher, the 9 best documentaries about steven tyler.

Discover New Content

The woman who lived in sin with a dolphin

In 1965, Margaret Howe moved into a flooded house with a dolphin. She intended to teach the animal to talk, but there was something he wanted from her in return...

From outside it looked like another spacious Virgin Islands villa with a spiral staircase twisting up to a sunny balcony overlooking the Caribbean Sea. But Dolphin Point Laboratory on the island of St Thomas was part of a unique Washington-funded research institute run by Dr John C Lilly , the wackiest and most polarising figure in marine science history. A medic and neurologist by training, a mystic by inclination, he was intent on furthering his investigations into the communication skills of dolphins, who he believed could help us talk to extraterrestrials.

For 10 weeks, from June to August 1965, the St Thomas research centre became the site of Lilly’s most notorious and highly criticised experiment, when his young assistant, Margaret Howe, volunteered to live in confinement with Peter, a bottlenose dolphin. The dolphin house was flooded with water and redesigned for a specific purpose: to allow the 23-year-old Howe and the dolphin to live, sleep, eat, wash and play intimately together. The objective of the experiment was to see whether a dolphin could be taught human speech – a hypothesis that Lilly, in 1960, predicted could be a reality “within a decade or two”.

Even dolphin experts who today hold some of Lilly’s other work in high regard believe it was deeply misguided. Media coverage has focused on two things: Howe’s almost total failure to teach Peter to speak; and the reluctant sexual relationship she began with the animal in an effort to put him at his ease. She has not spoken about her experiences for nearly 50 years (to “let [the story] fade”), but earlier this year accepted an interview request by the BBC producer Mark Hedgecoe, who thought it was “the most remarkable story of animal science I had ever heard”.

The result, a documentary called The Girl Who Talked to Dolphins, is set to premiere at Sheffield Doc/Fest and then on BBC Four later this month. Various films and documentaries have dissected some of the baffling, entertaining and ultimately tragic animal-human language experiments offered up by the Sixties and Seventies, most recently James Marsh’s 2011 feature Project Nim, about a chimp raised in a New York family . But what makes the dolphin house story unique is the intensity of the period of interspecies cohabitation. Howe and Peter lived in complete isolation.

READ: Attenborough documentaries ignore gay animals

Prof Thomas White, a philosopher and international leader in the field of dolphin ethics, believes the experiment was “cruel” and flawed from the outset. “Lilly was a pioneer,” he says. “Not just in the study of the dolphin brain; he was an open-minded scientist who speculated very early on that dolphins are self-aware creatures with emotional vulnerabilities that need an array of relationships to flourish. That should have made him think: ‘I really shouldn’t be doing this kind of thing.’ ”

Lilly, who had gained the scientific establishment’s respect with his work on the human brain, became interested in dolphins in the Fifties, after performing a series of “inner-consciousness” investigations on himself in which he floated around for hours in salt water in an effort to block outside stimuli and increase his sensitivity.

His 1961 book Man and Dolphin was an international bestseller. It was the first book to claim that dolphins displayed complex emotions – that they were capable of controlling anger, for example, and that they, like humans, often trembled in response to being hurt. Some dolphin species, he said, had brains up to 40 per cent larger than humans’. As well as being our “cognitive equal”, Lilly speculated they were capable of a form of telepathy that was the key to understanding extraterrestrial communication. He also believed they could “teach us to live in outer space without gravity”. He also proposed that they could be trained to serve the Navy as a “glorified seeing-eye” (a theory that became the basis of the 1973 sci-fi thriller Day of the Dolphin, despite Lilly’s best attempts to halt production).

But Lilly did little to burnish his credentials in the early Sixties when he started exploring the psychological research possibilities offered by lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). He took it himself, often while floating in his isolation tank. Lilly later pinpointed 1965, the year of the dolphin cohabitation experiment, as the year he came to “no longer regard the scientific viewpoint of total objectivity as the be-all and end-all”. It wouldn’t be wildly speculative to suggest that Lilly was – by today’s standards at least – not in quite the right frame of mind to be leading the dolphin project.

Looking back at his memories of the mid-Sixties in his autobiography, an impressionistic account in which he writes of himself in the third person (“He felt that he was merely a small microbe on a mudball, rotating around a G-star, two thirds of the way from Galactic centre…”), it is also apparent how removed he was from Howe’s work.

He writes: “In the midst of his enthusiasm he [Lilly] attempted to speak to [Howe] of his experiences.” Howe, in her early 20s, was not sympathetic. “If you want to do your experiments on solitude and LSD, please keep them in the isolation room. I am not curious or interested.”

Howe was among many keen young staff members he employed from the island. Only the bravest stayed with him any significant length of time; as Lilly noted in The Mind of the Dolphin (1967), the Tursiops (bottlenose) – chosen for study because its brain size was comparable to man’s – was larger and more powerful than most humans. They grew irritable and angry when mismanaged. Howe’s talent for communicating with the dolphins was exceptional and, as Lilly noted, her dedication was unmatched by anyone else in the faculty. “I will not interfere with that,” he wrote.

Still, he prepared the experiment. Following a week-long trial period, Lilly decided 10 weeks was the maximum time frame that both human and dolphin could survive comfortably in confinement. Objectives, regulations and a daily timetable were clear and precise. Howe’s aims were threefold: to make notes on interspecies isolation, to attempt to teach Peter to “speak”, and to gather information so that the living conditions might be improved for longer-term cohabitation.

On June 15 Howe moved in, her hair cut to a quarter-inch boy crop. All she needed was a swimming costume and a leotard for the cooler nights. The entire upstairs of the lab building and the balcony had been flooded with salt water 18in deep, which Peter could swim around in and Howe could wade through. A desk hung from the ceiling, and her bed was a suspended foam mattress that she later fitted with a shower curtain so that Peter’s splashes did not soak her through the night. She would live off canned food to minimise contact with outsiders.

“It was perfect,” she remembers today of her domestic dolphinarium. Early entries in her diary at the time reveal that, like a nervous new housewife, she made the best of things: “Cooking is fine. Cleaning is interesting… Each morning most of the dirt is neatly deposited at the foot of the elevator shaft. All I have to do is suck it up.” As for her companion, he spent “a good deal of his time in front of the mirror”, she noted. She was amused to find that during rare moments of contact with the outside world (mostly on the telephone) Peter talked “very loudly and in a competitive way” over the top of her.

Although he could be rambunctious, the archive footage of his lessons featured in the new BBC documentary reveal Peter to have been a curious, dedicated student. Lilly’s team had already established that dolphins could adjust the frequency of their squeaks and whistles to mimic human sounds, and claimed that during his time with Howe, Peter learnt to pronounce words such as “ball” and “diamond”, and to tell the difference between certain objects.

Howe was a creative, commendably patient teacher; when Peter struggled with certain sounds, particularly the “M” in her name, she came up with the inventive method of painting her face in thick white make-up and black lipstick so that he could clearly see the shape of her lips moving. “His eye was in [the] air looking at my mouth. There was no question… He really wanted to know: where is that noise coming from? What is the sound?” she remembers. “Eventually he kind of rolled over so that he would bubble [the ‘M’ sound] into the water.”

To those who lived and worked with Peter, his progress was perhaps clearer than it was to the outsider. The average viewer, on watching the BBC documentary, might conclude that the experiment was a failure. Kenneth Norris, an influential marine biologist, said of Lilly: “He started out as a capable scientist, but nothing he did was subject to measurement or truth, and that’s what scientists live by.” Experiments since 1965 have proved that dolphins have high levels of self-awareness and can understand human sign communication – but there is still little evidence that a dolphin language exists.

However, Peter’s linguistic progress was seemingly what kept Howe going when their relationship grew strained. Fed up and clearly exhausted by week three, she wrote at length about Peter whining and making loud noises night and day for no apparent reason: “I will do anything to break this… I lost my temper and nearly yelled at Peter… I am physically so pooped I can hardly stand… depression… wanting to get away… my mind is not all on the job.”

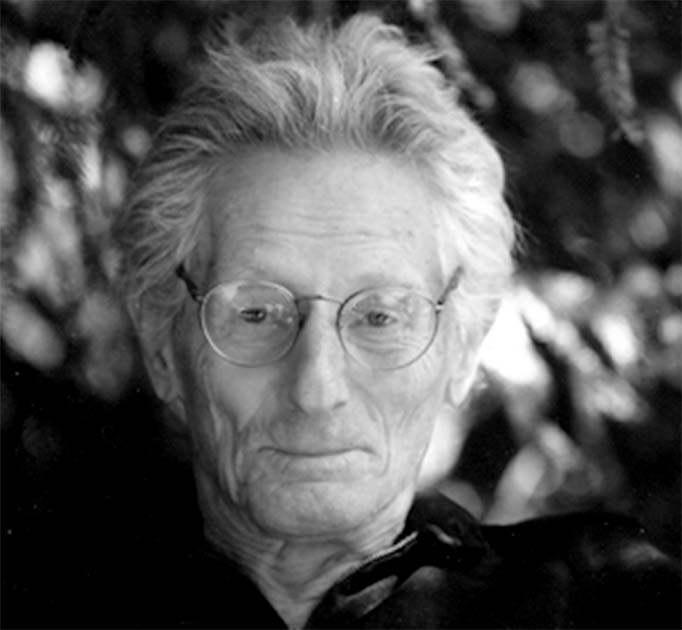

John C Lilly, pictured in 1977

Lilly, responding to Howe’s feedback, recorded his concerns. “This is a dull and small area… Isolation effects showing,” he wrote. Howe’s diary of week five is predominantly concerned with a new issue: “Peter begins having erections and has them frequently when I play with him.” Her frustrated efforts to deal with his “sexual needs” and advances – which had become so aggressive that her legs were covered in minor injuries from his jamming and nibbling – had left her scared. “Peter could bite me in two,” she wrote. But she was reluctant to hamper progress, and, in a spirit of pragmatism, decided to take matters into her own hands. As the narrator in the documentary tactfully puts it: “Margaret felt that the best way of focusing his mind back on his lessons was to relieve his desires herself manually.”

Sex among dolphins is a “normal way to establish a bond”, White says. “Dolphins are mostly bisexual, sometimes heterosexual, sometimes homosexual, and quite frequent – eight to 10 times a day I’ve been told – so it’s a very different culture that we’re looking at.” Peter’s sexual advances wouldn’t surprise any marine biologist. But what astonished Lilly was the complexity of the way Peter and Howe’s relationship developed from thereon in.

“New totally unexpected sequence of events took place,” Lilly noted excitedly. “I feel that we are in the midst of a new becoming; moving into a previous unknown…” As Peter became increasingly gentle, tactile and sensitive to Howe’s feelings he began to “woo” her by softly stroking his teeth up and down her legs. “I stand very still, legs slightly apart, and Peter slides his mouth gently over my shin,” she wrote in her diary. “Peter is courting me… he has been most persistent and patient… Obviously a sexy business… The mood is very gentle, still and hushed… all movements are slow.” Today she talks about the whole experience philosophically: “It was very precious. It was very gentle… It was sexual on his part. It was not sexual on mine. Sensual, perhaps.”

Howe’s writing also reflects her increasingly protective feelings towards Peter, and at the end of her diary she admits that Peter’s attentiveness helped her overcome her “depression” and “fits of self-pity”.

In a neat romantic twist, it all ended happily for Howe. She left the lab to marry the project’s photographer, John Lovatt. Though dismayed to lose her, even Lilly was pleased: “Her intraspecies needs are finally being taken care of.” She never returned to work for him. Soon after the experiment, Lilly’s funding began to dry up, and with his second marriage in tatters he left to explore mystical interests in South America.

As for Peter, the lab’s vet Andy Williamson remembers his concerns as the experiment came to a close: “It was great [Howe] wasn’t going to be damaged… but as a veterinarian, I wondered about poor Peter. This dolphin was madly in love with her.”

The unexpected consequences of the experiment highlight one of the persisting problems with the “short-sighted” scientific approach to animal intelligence, says White. “We focus on language as the primary indicator of intelligence. Dolphins, like humans, are very sophisticated emotionally as well as intellectually. From an ethical standpoint, that’s what we should be looking at.”

The Girl Who Talked to Dolphins will show at the Sheffield Doc/Fest on June 11 and on BBC Four on June 18

READ: How to get a giant panda pregnant

- Twitter Icon

- Facebook Icon

- WhatsApp Icon

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Margaret Howe Lovatt (born Margaret C. Howe, in 1942) is an American former volunteer naturalist from Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.In the 1960s, she took part in a NASA-funded research project in which she attempted to teach a dolphin named Peter to understand and mimic human speech.

Aug 17, 2024 · Lovatt remained in St. Thomas after the failed experiment. She married the original photographer that worked on the project. Together, they had three daughters and converted the abandoned Dolphin Point laboratory into a home for their family. Margaret Howe Lovatt didn’t speak publicly of the experiment for nearly 50 years.

Jun 6, 2014 · The dolphin house was flooded with water and redesigned for a specific purpose: to allow the 23-year-old Howe and the dolphin to live, sleep, eat, wash and play intimately together.

Altogether, the story of Margaret Howe Lovatt and the Dolphinarium experiment is a captivating, thought-provoking tale. It is every bit as riveting and scandalous as it sounds. Margaret Lovatt at the Dolphin House on St Thomas. Photograph: Lilly Estate The Dolphinarium Experiment. In the middle of the 1960s, fascinating research was underway.

Mar 31, 2024 · Delve into the intriguing story of the Dolphin House Experiment conducted by Dr. John C. Lilly and Margaret Howe in 1965 at Dolphin Point Laboratory in St. T...

Sep 29, 2023 · The ruins of the Dolphin House, circled, on the island of St Thomas in 2015. This is where the experiments were performed (Wayne Hsieh / CC BY-NC 2.0 ) Before the red flag of bestiality goes up in your mind, it is essential to note that Margaret never engaged in sex with Peter in a way humans engage in intercourse.

Oct 4, 2023 · The experiment took place inside an enclosed house designed specifically for dolphins – aptly referred to as the “Dolphin House”. Inside, a young woman named Margaret Howe Lovatt was tasked with teaching the dolphin Peter how to understand and use English words.

The Dolphin House lab would test dolphins and their ability to learn, understand and speak English. He was assisted by 23-year old Margaret Howe, who - as part of the experiment - lived in the flooded house for 10 to 12 weeks alone with a fully grown bottle-nosed dolphin named Peter.

Nov 4, 2023 · Conducted by eccentric yet renowned neuroscientist John Lilly, he set up a lab called Dolphin House on St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands to explore dolphin communication and learning abilities. John enlisted 23-year old Margaret Howe to assist him, who lived in the flooded house with a mature bottle-nosed dolphin named Peter for 10 to 12 weeks.

May 30, 2014 · The dolphin house was flooded with water and redesigned for a specific purpose: to allow the 23-year-old Howe and the dolphin to live, sleep, eat, wash and play intimately together.