How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

| Summarizing Conclusion | Impact of social media on adolescents’ mental health | In conclusion, our study has shown that increased usage of social media is significantly associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression among adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the complex relationship between social media and mental health to develop effective interventions and support systems for this vulnerable population. |

| Editorial Conclusion | Environmental impact of plastic waste | In light of our research findings, it is clear that we are facing a plastic pollution crisis. To mitigate this issue, we strongly recommend a comprehensive ban on single-use plastics, increased recycling initiatives, and public awareness campaigns to change consumer behavior. The responsibility falls on governments, businesses, and individuals to take immediate actions to protect our planet and future generations. |

| Externalizing Conclusion | Exploring applications of AI in healthcare | While our study has provided insights into the current applications of AI in healthcare, the field is rapidly evolving. Future research should delve deeper into the ethical, legal, and social implications of AI in healthcare, as well as the long-term outcomes of AI-driven diagnostics and treatments. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, medical professionals, and policymakers is essential to harness the full potential of AI while addressing its challenges. |

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to write a high-quality conference paper.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 9. The Conclusion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The conclusion is intended to help the reader understand why your research should matter to them after they have finished reading the paper. A conclusion is not merely a summary of the main topics covered or a re-statement of your research problem, but a synthesis of key points derived from the findings of your study and, if applicable based on your analysis, explain new areas for future research. For most college-level research papers, two or three well-developed paragraphs is sufficient for a conclusion, although in some cases, more paragraphs may be required in describing the key findings and highlighting their significance.

Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of a Good Conclusion

A well-written conclusion provides important opportunities to demonstrate to the reader your understanding of the research problem. These include:

- Presenting the last word on the issues you raised in your paper . Just as the introduction gives a first impression to your reader, the conclusion offers a chance to leave a lasting impression. Do this, for example, by highlighting key findings in your analysis that advance new understanding about the research problem, that are unusual or unexpected, or that have important implications applied to practice.

- Summarizing your thoughts and conveying the larger significance of your study . The conclusion is an opportunity to succinctly re-emphasize your answer to the "So What?" question by placing the study within the context of how your research advances past studies about the topic.

- Identifying how a gap in the literature has been addressed . The conclusion can be where you describe how a previously identified gap in the literature [first identified in your literature review section] has been addressed by your research and why this contribution is significant.

- Demonstrating the importance of your ideas . Don't be shy. The conclusion offers an opportunity to elaborate on the impact and significance of your findings. This is particularly important if your study approached examining the research problem from an unusual or innovative perspective.

- Introducing possible new or expanded ways of thinking about the research problem . This does not refer to introducing new information [which should be avoided], but to offer new insight and creative approaches for framing or contextualizing the research problem based on the results of your study.

Bunton, David. “The Structure of PhD Conclusion Chapters.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4 (July 2005): 207–224; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

The general function of your paper's conclusion is to restate the main argument . It reminds the reader of your main argument(s) strengths and reiterates the most important evidence supporting those argument(s). Do this by clearly summarizing the context, background, and the necessity of examining the research problem in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found in the literature. However, make sure that your conclusion is not simply a repetitive summary of the findings. This reduces the impact of the argument(s) you have developed in your paper.

When writing the conclusion to your paper, follow these general rules:

- Present your conclusions in clear, concise language. Re-state the purpose of your study, then describe how your findings differ or support those of other studies and why [i.e., describe what were the unique, new, or crucial contributions your study made to the overall research about your topic].

- Do not simply reiterate your findings or the discussion of your results. Provide a synthesis of arguments presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem and the overall objectives of your study.

- Indicate opportunities for future research if you haven't already done so in the discussion section of your paper. Highlighting the need for further research provides the reader with evidence that you have an in-depth awareness of the research problem but that further analysis should take place beyond the scope of your investigation.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is presented well:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If, prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from the data [this is opposite of the introduction, which begins with general discussion of the context and ends with a detailed description of the research problem].

The conclusion also provides a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with all the information about the topic . Depending on the discipline you are writing in, the concluding paragraph may contain your reflections on the evidence presented. However, the nature of being introspective about the research you have conducted will depend on the topic and whether your professor wants you to express your observations in this way. If asked to think introspectively about the topic, do not delve into idle speculation. Being introspective means looking within yourself as an author to try and understand an issue more deeply, not to guess at possible outcomes or make up scenarios not supported by the evidence.

II. Developing a Compelling Conclusion

Although an effective conclusion needs to be clear and succinct, it does not need to be written passively or lack a compelling narrative. Strategies to help you move beyond merely summarizing the key points of your research paper may include any of the following:

- If your paper addresses a critical, contemporary problem, warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem proactively based on the evidence presented in your study.

- Recommend a specific course or courses of action that, if adopted, could address a specific problem in practice or in the development of new knowledge leading to positive change.

- Cite a relevant quotation or expert opinion already noted in your paper in order to lend authority and support to the conclusion(s) you have reached [a good source would be from a source cited in your literature review].

- Explain the consequences of your research in a way that elicits action or demonstrates urgency in seeking change.

- Restate a key statistic, fact, or visual image to emphasize the most important finding of your paper.

- If your discipline encourages personal reflection, illustrate your concluding point by drawing from your own life experiences.

- Return to an anecdote, an example, or a quotation that you presented in your introduction, but add further insight derived from the findings of your study; use your interpretation of results from your study to recast it in new or important ways.

- Provide a "take-home" message in the form of a succinct, declarative statement that you want the reader to remember about your study.

III. Problems to Avoid

Failure to be concise Your conclusion section should be concise and to the point. Conclusions that are too lengthy often have unnecessary information in them. The conclusion is not the place for details about your methodology or results. Although you should give a summary of what was learned from your research, this summary should be relatively brief, since the emphasis in the conclusion is on the implications, evaluations, insights, and other forms of analysis that you make. Strategies for writing concisely can be found here .

Failure to comment on larger, more significant issues In the introduction, your task was to move from the general [topic studied within the field of study] to the specific [the research problem]. However, in the conclusion, your task is to move the discussion from specific [your research problem] back to a general discussion framed around the implications and significance of your findings [i.e., how your research contributes new understanding or fills an important gap in the literature]. In short, the conclusion is where you should place your research within a larger context [visualize the structure of your paper as an hourglass--start with a broad introduction and review of the literature, move to the specific method of analysis and the discussion, conclude with a broad summary of the study's implications and significance].

Failure to reveal problems and negative results Negative aspects of the research process should never be ignored. These are problems, deficiencies, or challenges encountered during your study. They should be summarized as a way of qualifying your overall conclusions. If you encountered negative or unintended results [i.e., findings that are validated outside the research context in which they were generated], you must report them in the results section and discuss their implications in the discussion section of your paper. In the conclusion, use negative or surprising results as an opportunity to explain their possible significance and/or how they may form the basis for future research.

Failure to provide a clear summary of what was learned In order to discuss how your research fits within your field of study [and possibly the world at large], you need to summarize briefly and succinctly how it contributes to new knowledge or a new understanding about the research problem. This element of your conclusion may be only a few sentences long, but it often represents the key takeaway for your reader.

Failure to match the objectives of your research Often research objectives in the social and behavioral sciences change while the research is being carried out due to unforeseen factors or unanticipated variables. This is not a problem unless you forget to go back and refine the original objectives in your introduction. As these changes emerge they must be documented so that they accurately reflect what you were trying to accomplish in your research [not what you thought you might accomplish when you began].

Resist the urge to apologize If you've immersed yourself in studying the research problem, you presumably should know a good deal about it [perhaps even more than your professor!]. Nevertheless, by the time you have finished writing, you may be having some doubts about what you have produced. Repress those doubts! Don't undermine your authority as a researcher by saying something like, "This is just one approach to examining this problem; there may be other, much better approaches that...." The overall tone of your conclusion should convey confidence to the reader concerning the validity and realiability of your research.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Concluding Paragraphs. College Writing Center at Meramec. St. Louis Community College; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Leibensperger, Summer. Draft Your Conclusion. Academic Center, the University of Houston-Victoria, 2003; Make Your Last Words Count. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin Madison; Miquel, Fuster-Marquez and Carmen Gregori-Signes. “Chapter Six: ‘Last but Not Least:’ Writing the Conclusion of Your Paper.” In Writing an Applied Linguistics Thesis or Dissertation: A Guide to Presenting Empirical Research . John Bitchener, editor. (Basingstoke,UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 93-105; Tips for Writing a Good Conclusion. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Writing Conclusions. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Don't Belabor the Obvious!

Avoid phrases like "in conclusion...," "in summary...," or "in closing...." These phrases can be useful, even welcome, in oral presentations. But readers can see by the tell-tale section heading and number of pages remaining that they are reaching the end of your paper. You'll irritate your readers if you belabor the obvious.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Another Writing Tip

New Insight, Not New Information!

Don't surprise the reader with new information in your conclusion that was never referenced anywhere else in the paper. This is why the conclusion rarely has citations to sources that haven't been referenced elsewhere in your paper. If you have new information to present, add it to the discussion or other appropriate section of the paper. Note that, although no new information is introduced, the conclusion, along with the discussion section, is where you offer your most "original" contributions in the paper; the conclusion is where you describe the value of your research, demonstrate that you understand the material that you have presented, and position your findings within the larger context of scholarship on the topic, including describing how your research contributes new insights to that scholarship.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: Limitations of the Study

- Next: Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Aug 13, 2024 12:57 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Conclusion

Definition:

A research paper conclusion is the final section of a research paper that summarizes the key findings, significance, and implications of the research. It is the writer’s opportunity to synthesize the information presented in the paper, draw conclusions, and make recommendations for future research or actions.

The conclusion should provide a clear and concise summary of the research paper, reiterating the research question or problem, the main results, and the significance of the findings. It should also discuss the limitations of the study and suggest areas for further research.

Parts of Research Paper Conclusion

The parts of a research paper conclusion typically include:

Restatement of the Thesis

The conclusion should begin by restating the thesis statement from the introduction in a different way. This helps to remind the reader of the main argument or purpose of the research.

Summary of Key Findings

The conclusion should summarize the main findings of the research, highlighting the most important results and conclusions. This section should be brief and to the point.

Implications and Significance

In this section, the researcher should explain the implications and significance of the research findings. This may include discussing the potential impact on the field or industry, highlighting new insights or knowledge gained, or pointing out areas for future research.

Limitations and Recommendations

It is important to acknowledge any limitations or weaknesses of the research and to make recommendations for how these could be addressed in future studies. This shows that the researcher is aware of the potential limitations of their work and is committed to improving the quality of research in their field.

Concluding Statement

The conclusion should end with a strong concluding statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. This could be a call to action, a recommendation for further research, or a final thought on the topic.

How to Write Research Paper Conclusion

Here are some steps you can follow to write an effective research paper conclusion:

- Restate the research problem or question: Begin by restating the research problem or question that you aimed to answer in your research. This will remind the reader of the purpose of your study.

- Summarize the main points: Summarize the key findings and results of your research. This can be done by highlighting the most important aspects of your research and the evidence that supports them.

- Discuss the implications: Discuss the implications of your findings for the research area and any potential applications of your research. You should also mention any limitations of your research that may affect the interpretation of your findings.

- Provide a conclusion : Provide a concise conclusion that summarizes the main points of your paper and emphasizes the significance of your research. This should be a strong and clear statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

- Offer suggestions for future research: Lastly, offer suggestions for future research that could build on your findings and contribute to further advancements in the field.

Remember that the conclusion should be brief and to the point, while still effectively summarizing the key findings and implications of your research.

Example of Research Paper Conclusion

Here’s an example of a research paper conclusion:

Conclusion :

In conclusion, our study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students. Our findings suggest that there is a significant association between social media use and increased levels of anxiety and depression among college students. This highlights the need for increased awareness and education about the potential negative effects of social media use on mental health, particularly among college students.

Despite the limitations of our study, such as the small sample size and self-reported data, our findings have important implications for future research and practice. Future studies should aim to replicate our findings in larger, more diverse samples, and investigate the potential mechanisms underlying the association between social media use and mental health. In addition, interventions should be developed to promote healthy social media use among college students, such as mindfulness-based approaches and social media detox programs.

Overall, our study contributes to the growing body of research on the impact of social media on mental health, and highlights the importance of addressing this issue in the context of higher education. By raising awareness and promoting healthy social media use among college students, we can help to reduce the negative impact of social media on mental health and improve the well-being of young adults.

Purpose of Research Paper Conclusion

The purpose of a research paper conclusion is to provide a summary and synthesis of the key findings, significance, and implications of the research presented in the paper. The conclusion serves as the final opportunity for the writer to convey their message and leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The conclusion should restate the research problem or question, summarize the main results of the research, and explain their significance. It should also acknowledge the limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research or action.

Overall, the purpose of the conclusion is to provide a sense of closure to the research paper and to emphasize the importance of the research and its potential impact. It should leave the reader with a clear understanding of the main findings and why they matter. The conclusion serves as the writer’s opportunity to showcase their contribution to the field and to inspire further research and action.

When to Write Research Paper Conclusion

The conclusion of a research paper should be written after the body of the paper has been completed. It should not be written until the writer has thoroughly analyzed and interpreted their findings and has written a complete and cohesive discussion of the research.

Before writing the conclusion, the writer should review their research paper and consider the key points that they want to convey to the reader. They should also review the research question, hypotheses, and methodology to ensure that they have addressed all of the necessary components of the research.

Once the writer has a clear understanding of the main findings and their significance, they can begin writing the conclusion. The conclusion should be written in a clear and concise manner, and should reiterate the main points of the research while also providing insights and recommendations for future research or action.

Characteristics of Research Paper Conclusion

The characteristics of a research paper conclusion include:

- Clear and concise: The conclusion should be written in a clear and concise manner, summarizing the key findings and their significance.

- Comprehensive: The conclusion should address all of the main points of the research paper, including the research question or problem, the methodology, the main results, and their implications.

- Future-oriented : The conclusion should provide insights and recommendations for future research or action, based on the findings of the research.

- Impressive : The conclusion should leave a lasting impression on the reader, emphasizing the importance of the research and its potential impact.

- Objective : The conclusion should be based on the evidence presented in the research paper, and should avoid personal biases or opinions.

- Unique : The conclusion should be unique to the research paper and should not simply repeat information from the introduction or body of the paper.

Advantages of Research Paper Conclusion

The advantages of a research paper conclusion include:

- Summarizing the key findings : The conclusion provides a summary of the main findings of the research, making it easier for the reader to understand the key points of the study.

- Emphasizing the significance of the research: The conclusion emphasizes the importance of the research and its potential impact, making it more likely that readers will take the research seriously and consider its implications.

- Providing recommendations for future research or action : The conclusion suggests practical recommendations for future research or action, based on the findings of the study.

- Providing closure to the research paper : The conclusion provides a sense of closure to the research paper, tying together the different sections of the paper and leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

- Demonstrating the writer’s contribution to the field : The conclusion provides the writer with an opportunity to showcase their contribution to the field and to inspire further research and action.

Limitations of Research Paper Conclusion

While the conclusion of a research paper has many advantages, it also has some limitations that should be considered, including:

- I nability to address all aspects of the research: Due to the limited space available in the conclusion, it may not be possible to address all aspects of the research in detail.

- Subjectivity : While the conclusion should be objective, it may be influenced by the writer’s personal biases or opinions.

- Lack of new information: The conclusion should not introduce new information that has not been discussed in the body of the research paper.

- Lack of generalizability: The conclusions drawn from the research may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, limiting the generalizability of the study.

- Misinterpretation by the reader: The reader may misinterpret the conclusions drawn from the research, leading to a misunderstanding of the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and...

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and...

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Research Paper Title Page – Example and Making...

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

How to write a strong conclusion for your research paper

Last updated

17 February 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Writing a research paper is a chance to share your knowledge and hypothesis. It's an opportunity to demonstrate your many hours of research and prove your ability to write convincingly.

Ideally, by the end of your research paper, you'll have brought your readers on a journey to reach the conclusions you've pre-determined. However, if you don't stick the landing with a good conclusion, you'll risk losing your reader’s trust.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper involves a few important steps, including restating the thesis and summing up everything properly.

Find out what to include and what to avoid, so you can effectively demonstrate your understanding of the topic and prove your expertise.

- Why is a good conclusion important?

A good conclusion can cement your paper in the reader’s mind. Making a strong impression in your introduction can draw your readers in, but it's the conclusion that will inspire them.

- What to include in a research paper conclusion

There are a few specifics you should include in your research paper conclusion. Offer your readers some sense of urgency or consequence by pointing out why they should care about the topic you have covered. Discuss any common problems associated with your topic and provide suggestions as to how these problems can be solved or addressed.

The conclusion should include a restatement of your initial thesis. Thesis statements are strengthened after you’ve presented supporting evidence (as you will have done in the paper), so make a point to reintroduce it at the end.

Finally, recap the main points of your research paper, highlighting the key takeaways you want readers to remember. If you've made multiple points throughout the paper, refer to the ones with the strongest supporting evidence.

- Steps for writing a research paper conclusion

Many writers find the conclusion the most challenging part of any research project . By following these three steps, you'll be prepared to write a conclusion that is effective and concise.

- Step 1: Restate the problem

Always begin by restating the research problem in the conclusion of a research paper. This serves to remind the reader of your hypothesis and refresh them on the main point of the paper.

When restating the problem, take care to avoid using exactly the same words you employed earlier in the paper.

- Step 2: Sum up the paper

After you've restated the problem, sum up the paper by revealing your overall findings. The method for this differs slightly, depending on whether you're crafting an argumentative paper or an empirical paper.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

Argumentative papers involve introducing a thesis statement early on. In crafting the conclusion for an argumentative paper, always restate the thesis, outlining the way you've developed it throughout the entire paper.

It might be appropriate to mention any counterarguments in the conclusion, so you can demonstrate how your thesis is correct or how the data best supports your main points.

Empirical paper: Summarize research findings

Empirical papers break down a series of research questions. In your conclusion, discuss the findings your research revealed, including any information that surprised you.

Be clear about the conclusions you reached, and explain whether or not you expected to arrive at these particular ones.

- Step 3: Discuss the implications of your research

Argumentative papers and empirical papers also differ in this part of a research paper conclusion. Here are some tips on crafting conclusions for argumentative and empirical papers.

Argumentative paper: Powerful closing statement

In an argumentative paper, you'll have spent a great deal of time expressing the opinions you formed after doing a significant amount of research. Make a strong closing statement in your argumentative paper's conclusion to share the significance of your work.

You can outline the next steps through a bold call to action, or restate how powerful your ideas turned out to be.

Empirical paper: Directions for future research

Empirical papers are broader in scope. They usually cover a variety of aspects and can include several points of view.

To write a good conclusion for an empirical paper, suggest the type of research that could be done in the future, including methods for further investigation or outlining ways other researchers might proceed.

If you feel your research had any limitations, even if they were outside your control, you could mention these in your conclusion.

After you finish outlining your conclusion, ask someone to read it and offer feedback. In any research project you're especially close to, it can be hard to identify problem areas. Having a close friend or someone whose opinion you value read the research paper and provide honest feedback can be invaluable. Take note of any suggested edits and consider incorporating them into your paper if they make sense.

- Things to avoid in a research paper conclusion

Keep these aspects to avoid in mind as you're writing your conclusion and refer to them after you've created an outline.

Dry summary

Writing a memorable, succinct conclusion is arguably more important than a strong introduction. Take care to avoid just rephrasing your main points, and don't fall into the trap of repeating dry facts or citations.

You can provide a new perspective for your readers to think about or contextualize your research. Either way, make the conclusion vibrant and interesting, rather than a rote recitation of your research paper’s highlights.

Clichéd or generic phrasing

Your research paper conclusion should feel fresh and inspiring. Avoid generic phrases like "to sum up" or "in conclusion." These phrases tend to be overused, especially in an academic context and might turn your readers off.

The conclusion also isn't the time to introduce colloquial phrases or informal language. Retain a professional, confident tone consistent throughout your paper’s conclusion so it feels exciting and bold.

New data or evidence

While you should present strong data throughout your paper, the conclusion isn't the place to introduce new evidence. This is because readers are engaged in actively learning as they read through the body of your paper.

By the time they reach the conclusion, they will have formed an opinion one way or the other (hopefully in your favor!). Introducing new evidence in the conclusion will only serve to surprise or frustrate your reader.

Ignoring contradictory evidence

If your research reveals contradictory evidence, don't ignore it in the conclusion. This will damage your credibility as an expert and might even serve to highlight the contradictions.

Be as transparent as possible and admit to any shortcomings in your research, but don't dwell on them for too long.

Ambiguous or unclear resolutions

The point of a research paper conclusion is to provide closure and bring all your ideas together. You should wrap up any arguments you introduced in the paper and tie up any loose ends, while demonstrating why your research and data are strong.

Use direct language in your conclusion and avoid ambiguity. Even if some of the data and sources you cite are inconclusive or contradictory, note this in your conclusion to come across as confident and trustworthy.

- Examples of research paper conclusions

Your research paper should provide a compelling close to the paper as a whole, highlighting your research and hard work. While the conclusion should represent your unique style, these examples offer a starting point:

Ultimately, the data we examined all point to the same conclusion: Encouraging a good work-life balance improves employee productivity and benefits the company overall. The research suggests that when employees feel their personal lives are valued and respected by their employers, they are more likely to be productive when at work. In addition, company turnover tends to be reduced when employees have a balance between their personal and professional lives. While additional research is required to establish ways companies can support employees in creating a stronger work-life balance, it's clear the need is there.

Social media is a primary method of communication among young people. As we've seen in the data presented, most young people in high school use a variety of social media applications at least every hour, including Instagram and Facebook. While social media is an avenue for connection with peers, research increasingly suggests that social media use correlates with body image issues. Young girls with lower self-esteem tend to use social media more often than those who don't log onto social media apps every day. As new applications continue to gain popularity, and as more high school students are given smartphones, more research will be required to measure the effects of prolonged social media use.

What are the different kinds of research paper conclusions?

There are no formal types of research paper conclusions. Ultimately, the conclusion depends on the outline of your paper and the type of research you’re presenting. While some experts note that research papers can end with a new perspective or commentary, most papers should conclude with a combination of both. The most important aspect of a good research paper conclusion is that it accurately represents the body of the paper.

Can I present new arguments in my research paper conclusion?

Research paper conclusions are not the place to introduce new data or arguments. The body of your paper is where you should share research and insights, where the reader is actively absorbing the content. By the time a reader reaches the conclusion of the research paper, they should have formed their opinion. Introducing new arguments in the conclusion can take a reader by surprise, and not in a positive way. It might also serve to frustrate readers.

How long should a research paper conclusion be?

There's no set length for a research paper conclusion. However, it's a good idea not to run on too long, since conclusions are supposed to be succinct. A good rule of thumb is to keep your conclusion around 5 to 10 percent of the paper's total length. If your paper is 10 pages, try to keep your conclusion under one page.

What should I include in a research paper conclusion?

A good research paper conclusion should always include a sense of urgency, so the reader can see how and why the topic should matter to them. You can also note some recommended actions to help fix the problem and some obstacles they might encounter. A conclusion should also remind the reader of the thesis statement, along with the main points you covered in the paper. At the end of the conclusion, add a powerful closing statement that helps cement the paper in the mind of the reader.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

Published on September 15, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on July 18, 2023.

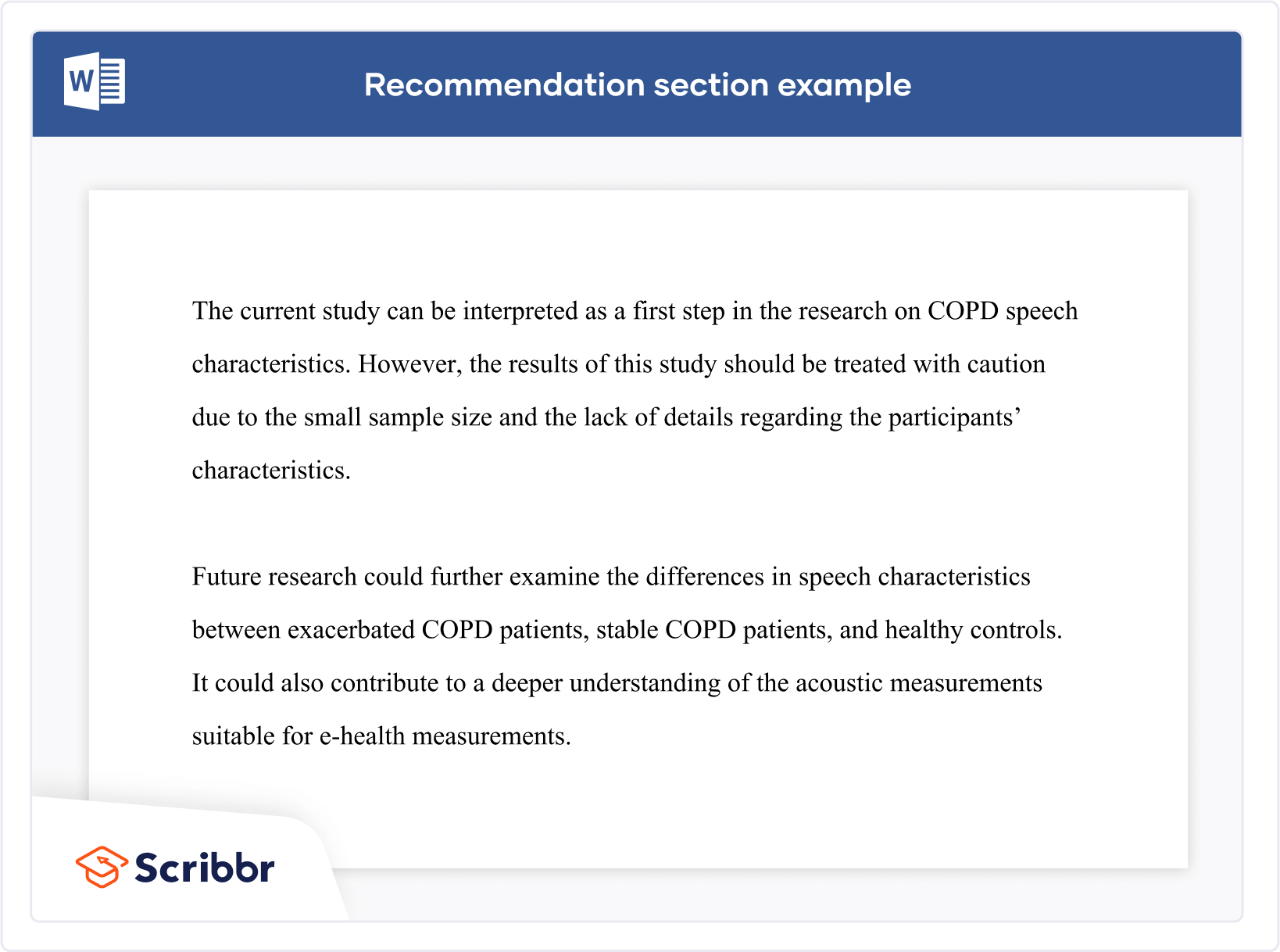

Recommendations in research are a crucial component of your discussion section and the conclusion of your thesis , dissertation , or research paper .

As you conduct your research and analyze the data you collected , perhaps there are ideas or results that don’t quite fit the scope of your research topic. Or, maybe your results suggest that there are further implications of your results or the causal relationships between previously-studied variables than covered in extant research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What should recommendations look like, building your research recommendation, how should your recommendations be written, recommendation in research example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about recommendations.

Recommendations for future research should be:

- Concrete and specific

- Supported with a clear rationale

- Directly connected to your research

Overall, strive to highlight ways other researchers can reproduce or replicate your results to draw further conclusions, and suggest different directions that future research can take, if applicable.

Relatedly, when making these recommendations, avoid:

- Undermining your own work, but rather offer suggestions on how future studies can build upon it

- Suggesting recommendations actually needed to complete your argument, but rather ensure that your research stands alone on its own merits

- Using recommendations as a place for self-criticism, but rather as a natural extension point for your work

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

There are many different ways to frame recommendations, but the easiest is perhaps to follow the formula of research question conclusion recommendation. Here’s an example.

Conclusion An important condition for controlling many social skills is mastering language. If children have a better command of language, they can express themselves better and are better able to understand their peers. Opportunities to practice social skills are thus dependent on the development of language skills.

As a rule of thumb, try to limit yourself to only the most relevant future recommendations: ones that stem directly from your work. While you can have multiple recommendations for each research conclusion, it is also acceptable to have one recommendation that is connected to more than one conclusion.

These recommendations should be targeted at your audience, specifically toward peers or colleagues in your field that work on similar subjects to your paper or dissertation topic . They can flow directly from any limitations you found while conducting your work, offering concrete and actionable possibilities for how future research can build on anything that your own work was unable to address at the time of your writing.

See below for a full research recommendation example that you can use as a template to write your own.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

While it may be tempting to present new arguments or evidence in your thesis or disseration conclusion , especially if you have a particularly striking argument you’d like to finish your analysis with, you shouldn’t. Theses and dissertations follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the discussion section and results section .) The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation should include the following:

- A restatement of your research question

- A summary of your key arguments and/or results

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

For a stronger dissertation conclusion , avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the discussion section and results section

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion …”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g., “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved August 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/recommendations-in-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a results section | tips & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How To Write The Conclusion Chapter

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | September 2021

So, you’ve wrapped up your results and discussion chapters, and you’re finally on the home stretch – the conclusion chapter . In this post, we’ll discuss everything you need to know to craft a high-quality conclusion chapter for your dissertation or thesis project.

Overview: The Conclusion Chapter

- What the thesis/dissertation conclusion chapter is

- What to include in your conclusion

- How to structure and write up your conclusion

- A few tips to help you ace the chapter

- FREE conclusion template

What is the conclusion chapter?

The conclusion chapter is typically the final major chapter of a dissertation or thesis. As such, it serves as a concluding summary of your research findings and wraps up the document. While some publications such as journal articles and research reports combine the discussion and conclusion sections, these are typically separate chapters in a dissertation or thesis. As always, be sure to check what your university’s structural preference is before you start writing up these chapters.

So, what’s the difference between the discussion and the conclusion chapter?

Well, the two chapters are quite similar , as they both discuss the key findings of the study. However, the conclusion chapter is typically more general and high-level in nature. In your discussion chapter, you’ll typically discuss the intricate details of your study, but in your conclusion chapter, you’ll take a broader perspective, reporting on the main research outcomes and how these addressed your research aim (or aims) .

A core function of the conclusion chapter is to synthesise all major points covered in your study and to tell the reader what they should take away from your work. Basically, you need to tell them what you found , why it’s valuable , how it can be applied , and what further research can be done.

Whatever you do, don’t just copy and paste what you’ve written in your discussion chapter! The conclusion chapter should not be a simple rehash of the discussion chapter. While the two chapters are similar, they have distinctly different functions.

What should I include in the conclusion chapter?

To understand what needs to go into your conclusion chapter, it’s useful to understand what the chapter needs to achieve. In general, a good dissertation conclusion chapter should achieve the following:

- Summarise the key findings of the study

- Explicitly answer the research question(s) and address the research aims

- Inform the reader of the study’s main contributions

- Discuss any limitations or weaknesses of the study

- Present recommendations for future research

Therefore, your conclusion chapter needs to cover these core components. Importantly, you need to be careful not to include any new findings or data points. Your conclusion chapter should be based purely on data and analysis findings that you’ve already presented in the earlier chapters. If there’s a new point you want to introduce, you’ll need to go back to your results and discussion chapters to weave the foundation in there.

In many cases, readers will jump from the introduction chapter directly to the conclusions chapter to get a quick overview of the study’s purpose and key findings. Therefore, when you write up your conclusion chapter, it’s useful to assume that the reader hasn’t consumed the inner chapters of your dissertation or thesis. In other words, craft your conclusion chapter such that there’s a strong connection and smooth flow between the introduction and conclusion chapters, even though they’re on opposite ends of your document.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the conclusion chapter

Now that you have a clearer view of what the conclusion chapter is about, let’s break down the structure of this chapter so that you can get writing. Keep in mind that this is merely a typical structure – it’s not set in stone or universal. Some universities will prefer that you cover some of these points in the discussion chapter , or that you cover the points at different levels in different chapters.

Step 1: Craft a brief introduction section

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, the conclusions chapter needs to start with a brief introduction. In this introductory section, you’ll want to tell the reader what they can expect to find in the chapter, and in what order . Here’s an example of what this might look like:

This chapter will conclude the study by summarising the key research findings in relation to the research aims and questions and discussing the value and contribution thereof. It will also review the limitations of the study and propose opportunities for future research.

Importantly, the objective here is just to give the reader a taste of what’s to come (a roadmap of sorts), not a summary of the chapter. So, keep it short and sweet – a paragraph or two should be ample.

Step 2: Discuss the overall findings in relation to the research aims

The next step in writing your conclusions chapter is to discuss the overall findings of your study , as they relate to the research aims and research questions . You would have likely covered similar ground in the discussion chapter, so it’s important to zoom out a little bit here and focus on the broader findings – specifically, how these help address the research aims .

In practical terms, it’s useful to start this section by reminding your reader of your research aims and research questions, so that the findings are well contextualised. In this section, phrases such as, “This study aimed to…” and “the results indicate that…” will likely come in handy. For example, you could say something like the following:

This study aimed to investigate the feeding habits of the naked mole-rat. The results indicate that naked mole rats feed on underground roots and tubers. Further findings show that these creatures eat only a part of the plant, leaving essential parts to ensure long-term food stability.

Be careful not to make overly bold claims here. Avoid claims such as “this study proves that” or “the findings disprove existing the existing theory”. It’s seldom the case that a single study can prove or disprove something. Typically, this is achieved by a broader body of research, not a single study – especially not a dissertation or thesis which will inherently have significant limitations . We’ll discuss those limitations a little later.

Step 3: Discuss how your study contributes to the field

Next, you’ll need to discuss how your research has contributed to the field – both in terms of theory and practice . This involves talking about what you achieved in your study, highlighting why this is important and valuable, and how it can be used or applied.

In this section you’ll want to:

- Mention any research outputs created as a result of your study (e.g., articles, publications, etc.)

- Inform the reader on just how your research solves your research problem , and why that matters

- Reflect on gaps in the existing research and discuss how your study contributes towards addressing these gaps

- Discuss your study in relation to relevant theories . For example, does it confirm these theories or constructively challenge them?

- Discuss how your research findings can be applied in the real world . For example, what specific actions can practitioners take, based on your findings?

Be careful to strike a careful balance between being firm but humble in your arguments here. It’s unlikely that your one study will fundamentally change paradigms or shake up the discipline, so making claims to this effect will be frowned upon . At the same time though, you need to present your arguments with confidence, firmly asserting the contribution your research has made, however small that contribution may be. Simply put, you need to keep it balanced .

Step 4: Reflect on the limitations of your study

Now that you’ve pumped your research up, the next step is to critically reflect on the limitations and potential shortcomings of your study. You may have already covered this in the discussion chapter, depending on your university’s structural preferences, so be careful not to repeat yourself unnecessarily.

There are many potential limitations that can apply to any given study. Some common ones include:

- Sampling issues that reduce the generalisability of the findings (e.g., non-probability sampling )

- Insufficient sample size (e.g., not getting enough survey responses ) or limited data access

- Low-resolution data collection or analysis techniques

- Researcher bias or lack of experience

- Lack of access to research equipment

- Time constraints that limit the methodology (e.g. cross-sectional vs longitudinal time horizon)

- Budget constraints that limit various aspects of the study

Discussing the limitations of your research may feel self-defeating (no one wants to highlight their weaknesses, right), but it’s a critical component of high-quality research. It’s important to appreciate that all studies have limitations (even well-funded studies by expert researchers) – therefore acknowledging these limitations adds credibility to your research by showing that you understand the limitations of your research design .

That being said, keep an eye on your wording and make sure that you don’t undermine your research . It’s important to strike a balance between recognising the limitations, but also highlighting the value of your research despite those limitations. Show the reader that you understand the limitations, that these were justified given your constraints, and that you know how they can be improved upon – this will get you marks.

Next, you’ll need to make recommendations for future studies. This will largely be built on the limitations you just discussed. For example, if one of your study’s weaknesses was related to a specific data collection or analysis method, you can make a recommendation that future researchers undertake similar research using a more sophisticated method.

Another potential source of future research recommendations is any data points or analysis findings that were interesting or surprising , but not directly related to your study’s research aims and research questions. So, if you observed anything that “stood out” in your analysis, but you didn’t explore it in your discussion (due to a lack of relevance to your research aims), you can earmark that for further exploration in this section.

Essentially, this section is an opportunity to outline how other researchers can build on your study to take the research further and help develop the body of knowledge. So, think carefully about the new questions that your study has raised, and clearly outline these for future researchers to pick up on.

Step 6: Wrap up with a closing summary

Tips for a top-notch conclusion chapter

Now that we’ve covered the what , why and how of the conclusion chapter, here are some quick tips and suggestions to help you craft a rock-solid conclusion.

- Don’t ramble . The conclusion chapter usually consumes 5-7% of the total word count (although this will vary between universities), so you need to be concise. Edit this chapter thoroughly with a focus on brevity and clarity.

- Be very careful about the claims you make in terms of your study’s contribution. Nothing will make the marker’s eyes roll back faster than exaggerated or unfounded claims. Be humble but firm in your claim-making.

- Use clear and simple language that can be easily understood by an intelligent layman. Remember that not every reader will be an expert in your field, so it’s important to make your writing accessible. Bear in mind that no one knows your research better than you do, so it’s important to spell things out clearly for readers.

Hopefully, this post has given you some direction and confidence to take on the conclusion chapter of your dissertation or thesis with confidence. If you’re still feeling a little shaky and need a helping hand, consider booking a free initial consultation with a friendly Grad Coach to discuss how we can help you with hands-on, private coaching.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

17 Comments

Really you team are doing great!

Your guide on writing the concluding chapter of a research is really informative especially to the beginners who really do not know where to start. Im now ready to start. Keep it up guys

Really your team are doing great!

Very helpful guidelines, timely saved. Thanks so much for the tips.

This post was very helpful and informative. Thank you team.

A very enjoyable, understandable and crisp presentation on how to write a conclusion chapter. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Thanks Jenna.

This was a very helpful article which really gave me practical pointers for my concluding chapter. Keep doing what you are doing! It meant a lot to me to be able to have this guide. Thank you so much.

Nice content dealing with the conclusion chapter, it’s a relief after the streneous task of completing discussion part.Thanks for valuable guidance

Thanks for your guidance

I get all my doubts clarified regarding the conclusion chapter. It’s really amazing. Many thanks.

Very helpful tips. Thanks so much for the guidance

Thank you very much for this piece. It offers a very helpful starting point in writing the conclusion chapter of my thesis.

It’s awesome! Most useful and timely too. Thanks a million times

Bundle of thanks for your guidance. It was greatly helpful.

Wonderful, clear, practical guidance. So grateful to read this as I conclude my research. Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

- Posted on May 12, 2023

The key to an impactful research paper is crafting an effective conclusion. The conclusion provides a final opportunity to make a lasting impression on the reader by providing a powerful summary of the main argument and key findings.

A well-written conclusion not only summarizes your research but also ties everything back to your thesis statement. Plus, it provides important takeaways for your reader, highlighting what they should remember from your research and how it contributes to the larger academic discourse.

Crafting an impactful conclusion can be tricky, especially in argumentative papers. However, with our expert tips and tricks, you can rest assured that your conclusion will effectively restate the main argument and thesis statement in a way that resonates with your audience and elevates your research to new heights.

Why is a Conclusion Necessary for a Research Paper?