2.1 Why Is Research Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( Figure 2.2 ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behavior is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behavior by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades. Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores (Shaw & Tan, 2015). Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills (Massimini & Peterson, 2009). Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student's acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children's development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life (Blann, 2005). While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective (Neil & Christensen, 2009; Peters-Scheffer, Didden, Korzilius, & Sturmey, 2011). While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants (Barnett, 2011). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about early childhood program effectiveness to learn how scientists evaluate effectiveness and how best to invest money into programs that are most effective.

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine that your sister, Maria, expresses concern about her two-year-old child, Umberto. Umberto does not speak as much or as clearly as the other children in his daycare or others in the family. Umberto's pediatrician undertakes some screening and recommends an evaluation by a speech pathologist, but does not refer Maria to any other specialists. Maria is concerned that Umberto's speech delays are signs of a developmental disorder, but Umberto's pediatrician does not; she sees indications of differences in Umberto's jaw and facial muscles. Hearing this, you do some internet searches, but you are overwhelmed by the breadth of information and the wide array of sources. You see blog posts, top-ten lists, advertisements from healthcare providers, and recommendations from several advocacy organizations. Why are there so many sites? Which are based in research, and which are not?

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

NOTABLE RESEARCHERS

Psychological research has a long history involving important figures from diverse backgrounds. While the introductory chapter discussed several researchers who made significant contributions to the discipline, there are many more individuals who deserve attention in considering how psychology has advanced as a science through their work ( Figure 2.3 ). For instance, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) was the first woman to earn a PhD in psychology. Her research focused on animal behavior and cognition (Margaret Floy Washburn, PhD, n.d.). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was a preeminent first-generation American psychologist who opposed the behaviorist movement, conducted significant research into memory, and established one of the earliest experimental psychology labs in the United States (Mary Whiton Calkins, n.d.).

Francis Sumner (1895–1954) was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in 1920. His dissertation focused on issues related to psychoanalysis. Sumner also had research interests in racial bias and educational justice. Sumner was one of the founders of Howard University’s department of psychology, and because of his accomplishments, he is sometimes referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology.” Thirteen years later, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895–1934) became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in psychology. Prosser’s research highlighted issues related to education in segregated versus integrated schools, and ultimately, her work was very influential in the hallmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional (Ethnicity and Health in America Series: Featured Psychologists, n.d.).

Although the establishment of psychology’s scientific roots occurred first in Europe and the United States, it did not take much time until researchers from around the world began to establish their own laboratories and research programs. For example, some of the first experimental psychology laboratories in South America were founded by Horatio Piñero (1869–1919) at two institutions in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Godoy & Brussino, 2010). In India, Gunamudian David Boaz (1908–1965) and Narendra Nath Sen Gupta (1889–1944) established the first independent departments of psychology at the University of Madras and the University of Calcutta, respectively. These developments provided an opportunity for Indian researchers to make important contributions to the field (Gunamudian David Boaz, n.d.; Narendra Nath Sen Gupta, n.d.).

When the American Psychological Association (APA) was first founded in 1892, all of the members were White males (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.). However, by 1905, Mary Whiton Calkins was elected as the first female president of the APA, and by 1946, nearly one-quarter of American psychologists were female. Psychology became a popular degree option for students enrolled in the nation’s historically Black higher education institutions, increasing the number of Black Americans who went on to become psychologists. Given demographic shifts occurring in the United States and increased access to higher educational opportunities among historically underrepresented populations, there is reason to hope that the diversity of the field will increasingly match the larger population, and that the research contributions made by the psychologists of the future will better serve people of all backgrounds (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.).

The Process of Scientific Research

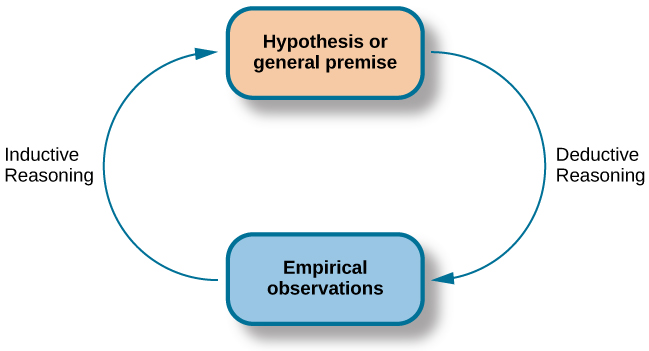

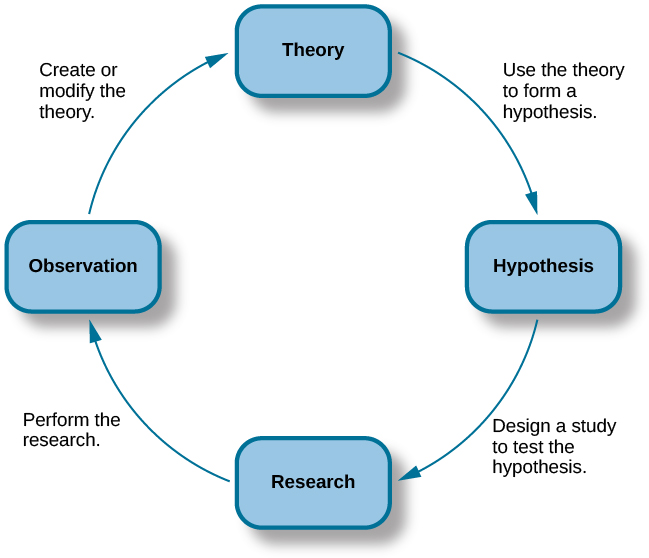

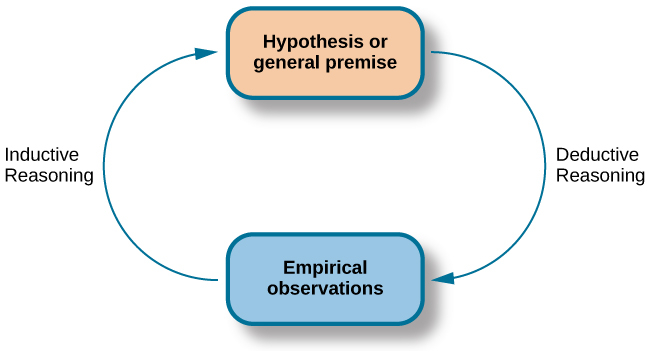

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas ( Figure 2.4 ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure 2.5 .

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

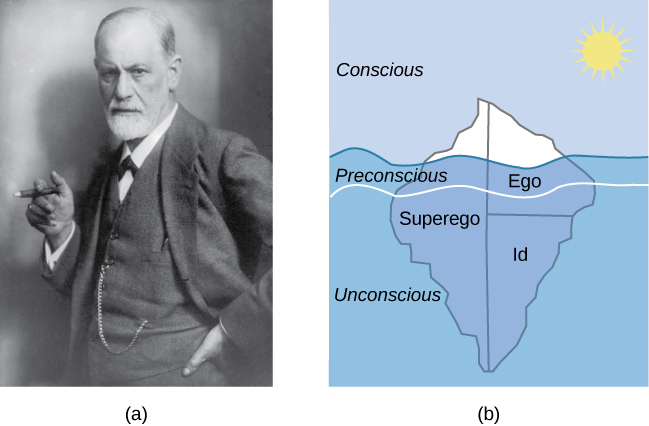

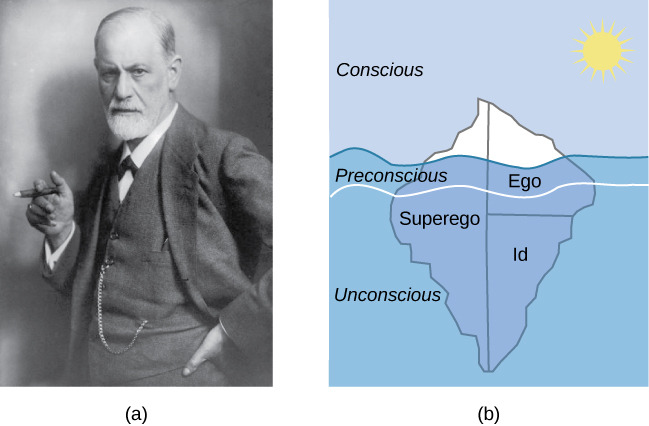

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable , or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors ( Figure 2.6 ). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/2-1-why-is-research-important

© Jun 26, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

PSYCH101: Introduction to Psychology

Why research is important.

Read this text, which introduces the scientific method, which involves making a hypothesis or general premise, deductive reasoning, making empirical observations, and inductive reasoning,

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people's authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth's continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession (Figure 2.2). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

Figure 2.2 Some of our ancestors, across the world and over the centuries, believed that trephination - the practice of making a hole in the skull, as shown here - allowed evil spirits to leave the body, thus curing mental illness and other disorders.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades.

Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores. Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills. Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student's acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health. In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on "scientific evidence" when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives. We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents' tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children's development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life.

While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective. While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants. If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund. Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine you just found out that your sister Maria's child, Umberto, was recently diagnosed with autism. There are many treatments for autism that help decrease the negative impact of autism on the individual. Some examples of treatments for autism are applied behavior analysis (ABA), social communication groups, social skills groups, occupational therapy, and even medication options. If Maria asked you for advice or guidance, what would you do? You would likely want to review the research and learn about the efficacy of each treatment so you could best advise your sister. In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

Notable Researchers

Psychological research has a long history involving important figures from diverse backgrounds. While the introductory chapter discussed several researchers who made significant contributions to the discipline, there are many more individuals who deserve attention in considering how psychology has advanced as a science through their work (Figure 2.3). For instance, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) was the first woman to earn a PhD in psychology. Her research focused on animal behavior and cognition. Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was a preeminent first-generation American psychologist who opposed the behaviorist movement, conducted significant research into memory, and established one of the earliest experimental psychology labs in the United States. Francis Sumner (1895–1954) was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in 1920. His dissertation focused on issues related to psychoanalysis. Sumner also had research interests in racial bias and educational justice. Sumner was one of the founders of Howard University's department of psychology, and because of his accomplishments, he is sometimes referred to as the "Father of Black Psychology". Thirteen years later, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895–1934) became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in psychology. Prosser's research highlighted issues related to education in segregated versus integrated schools, and ultimately, her work was very influential in the hallmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional.

Figure 2.3 (a) Margaret Floy Washburn was the first woman to earn a doctorate degree in psychology. (b) The outcome of Brown v. Board of Education was influenced by the research of psychologist Inez Beverly Prosser, who was the first African American woman to earn a PhD in psychology.

The Process of Scientific Research

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method. Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas (Figure 2.4). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization - one hypothesis - that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive. Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits - apples, bananas, and oranges - all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes. For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning. We've stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory. A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 The scientific method involves deriving hypotheses from theories and then testing those hypotheses. If the results are consistent with the theory, then the theory is supported. If the results are not consistent, then the theory should be modified and new hypotheses will be generated.

Figure 2.6 Many of the specifics of (a) Freud's theories, such as (b) his division of the mind into id, ego, and superego, have fallen out of favor in recent decades because they are not falsifiable. In broader strokes, his views set the stage for much of psychological thinking today, such as the unconscious nature of the majority of psychological processes.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2. Psychological Research

Why is Research Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behaviour

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession (see Figure 2). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behaviour, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behaviour. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behaviour of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behaviour is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behaviour. However, the reason for the behaviour is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behaviour by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behaviour. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the hypothesized link between exposure to media violence and subsequent aggression has been debated in the scientific community for roughly 60 years. Even today, we will find detractors, but a consensus is building. Several professional organizations view media violence exposure as a risk factor for actual violence, including the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Psychological Association (American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, American Psychological Association, American Medical Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

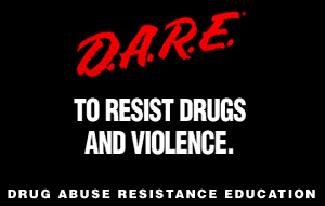

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding the D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program in public schools (see Figure 3). This program typically involves police officers coming into the classroom to educate students about the dangers of becoming involved with alcohol and other drugs. According to the D.A.R.E. website (www.dare.org), this program has been very popular since its inception in 1983, and it is currently operating in 75% of school districts in the United States and in more than 40 countries worldwide. According to D.A.R.E. BC, since its inception, more than 100,000 school children in British Columbia have gone through the program (http://darebc.com/) . Sounds like an easy decision, right? However, on closer review, you discover that the vast majority of research into this program consistently suggests that participation has little, if any, effect on whether or not someone uses alcohol or other drugs (Clayton, Cattarello, & Johnstone, 1996; Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, & Flewelling, 1994; Lynam et al., 1999; Ringwalt, Ennett, & Holt, 1991). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, will you fund this particular program, or will you try to find other programs that research has consistently demonstrated to be effective?

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine you just found out that a close friend has breast cancer or that one of your young relatives has recently been diagnosed with autism. In either case, you want to know which treatment options are most successful with the fewest side effects. How would you find that out? You would probably talk with your doctor and personally review the research that has been done on various treatment options—always with a critical eye to ensure that you are as informed as possible.

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

The Process of Scientific Research

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning, ideas are tested against the empirical world; in inductive reasoning, empirical observations lead to new ideas (see Figure 4). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favourite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests (see Figure 5).

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable, or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviours (see Figure 6). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

Activities: Watch a Video

OpenStax , Psychology. OpenStax CNX. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

DARE BC. http://darebc.com/

Introduction to Psychology I Copyright © 2017 by Rajiv Jhangiani, Ph.D. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Why is Research Important?

Learning Objectives

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behaviour

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( Figure PR.2 ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behaviour, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behaviour. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behaviour of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : it is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behaviour is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behaviour. However, the reason for the behaviour is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behaviour by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behaviour. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades. Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores (Shaw & Tan, 2015). Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills (Massimini & Peterson, 2009). Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student’s acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the Premier of your province. One of your responsibilities is to manage the provincial budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new Premier, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children’s development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life (Blann, 2005). While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective (Neil & Christensen, 2009; Peters-Scheffer, Didden, Korzilius, & Sturmey, 2011). While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants (Barnett, 2011). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund.

LINK TO LEARNING

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine you just found out that a close friend has breast cancer or that one of your young relatives has recently been diagnosed with autism. In either case, you want to know which treatment options are most successful with the fewest side effects. How would you find that out? You would probably talk with your doctor and personally review the research that has been done on various treatment options—always with a critical eye to ensure that you are as informed as possible.

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

The Process of Scientific Research

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas ( Figure PR.3 ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is supported, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favourite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure PR.4 .

Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience Copyright © 2020 by Edited by Leanne Stevens is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Theories and Explanations in Psychology

Anna m. borghi.

1 Department of Dynamic and Clinical Pyshcology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

2 Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, Italian National Research Council, Rome, Italy

Chiara Fini

Research in psychology has undergone many changes in the last 20 years. The increased and tighter relationship between psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy, the emergence and affirmation of embodied and grounded cognition approaches, the grow of interest on new research topics, the strengthening of new areas, such as the social, cognitive, and affective neuroscience, the spread of Bayesian models, and the recent debates on the replication crisis, represent some of the pieces of the new emerging landscape.

In spite of these novelties, one character of the discipline remains stable: its focus on empirical investigation. While we think this is an important and distinctive feature of our discipline, all too often this fascination for empirical data is accompanied by the absence of an equally deep interest for theory development. Noteworthy, while other scientific disciplines are endowed with a theoretical branch—think of the role of “theoretical physics” for physics—psychology does not have an equally institutionalized theoretical branch. This lack of theoretical interest is testified also by the fact that only few journals (Frontiers represents an exception) accept theoretical articles, i.e., articles that systematize existing evidence to inform a model or develop a new theory.

Here we argue that a strongly theoretical approach, that takes into account and seeks to identify the mechanisms underlying brain and mental processes, and that aims to build formal theories and computational models, can contribute to address the current limitations of psychological research helping it to face important challenges.

In the following we will highlight some limitations of psychological research, that a strong theoretical and philosophically informed approach can contribute to face.

A pivotal role in promoting interdisciplinarity can be played by philosophy—and in particular by philosophy of mind and language, philosophy of psychology, philosophy of neuroscience, and of cognitive science. Although not a natural science, empirically-informed philosophy can play a crucial integrative role, helping to build a more comprehensive view of the field and identifying links that cross disciplinary boundaries.

In a different way, computational models and simulations are instruments that boost interdisciplinarity: a good model has a cumulative character, it helps in theory building and in validation of empirical data coming from different sources and disciplines and obtained with different methods (Caligiore et al., 2010 ; Pezzulo et al., 2011 ).

One of the most debated issues in recent psychological research is the replication crisis, and in particular the reliability of scientific results. We do not intend to under-evaluate the attempts to strengthen the results and we really appreciate the recent tendency to distinguish confirmatory and exploratory research. We namely think that research in psychology needs to follow two strategies: a more explorative, and a more confirmative one-science has indeed two different sides, a creative and a monitoring one. Exerting either an inductive or a deductive logic might allow to build strong and reliable empirical-based psychological models.

However, we think that more resources and more effort should be devoted to find explanations of phenomena [see Van Rooij ( 2018 ) for convincing arguments on this]. As argued by Cummins ( 2000 ), “a substantial proportion of research effort in experimental psychology isn't expended directly in the explanation business; it is expended in the business of discovering and confirming effects.”

Based on these considerations, we believe that more emphasis should be given to the ability to plan and construct experiments with the aim of theory building rather than simply to find reliable effects. Not only the tendency to publish unsound results, but also the tendency to search “originality” at all costs without theory should be contrasted. This approach should clearly impact training, education, and also selection of young researchers.

The objective of ascribing a more crucial role to the theoretical foundations of our discipline can be reached in multiple ways. We will mention just a couple of them.

One possible strategy is to focus more on core mechanisms, adopting a synthetic approach. As clearly explained by Hommel and Colzato ( 2017 ) in a recent grand challenge, a mature science should “learn to value theoretical frameworks that track down core mechanisms in as many phenomena as possible,” and a more parsimonious approach should be promoted. One example is the role played by goals in influencing action representation, imitation, etc.

Another way to promote a synthetic approach consists in fostering the use of computational models. Computational models can namely help formulating clearer experimental hypotheses, refining theories, and validating them. Particularly promising are dynamic systems approach, neural networks models, Bayesian models.

- Epistemological awareness . It is important to understand where the field is going. Recent years have seen a variety of pivotal changes and modifications. The spread of embodied and grounded cognition has represented a real revolution in the areas of cognition and social cognition, and has determined an important paradigm change. In addition, we have assisted to the introduction of extended mind proposals, the increased role of social neuroscience and overall the development of a very tight relationship between psychology and neuroscience, the increased importance of Bayesian models. Experiments in psychology typically support or disconfirm field theories, but in many cases they do not explicitly relate to these more general approaches or theories. We instead believe that it is important for scientists to situate their own research within a broad theoretical framework, a general theory; this can namely help to form a cumulative baggage of knowledge.

- Key methodological challenges of psychology . The hotly debated replication crisis in science has been particularly deep in psychology. Addressing it in a proper way certainly requires methodological improvements, but also a clear epistemological vision of the specificity of psychological research. The field is divided between scientists who think it is important to address them improving replication, and scientists who think that research should be more focused on innovation and discovery. A strong theoretical approach can provide means to address this crisis, adopting synthetic methods that facilitate the identification of some basic mechanisms rather than focusing on a variety of more or less fashionable effects. It is important to foster debate on this topic, since its outcome may influence the future of our discipline. In addition, it is important to promote the discussion and use of different kinds of computational models, aimed at strengthening theoretical approaches.

- Cross-cultural research . Scholars are starting to recognize that psychological processes are far from being universal (Henrich et al., 2010 ; Prinz, 2012 ; Barrett, 2017 ; Hruschka et al., 2018 ). As a consequence, psychologists are starting to propose more and more cross-cultural research. The research instruments we now possess, allowing to perform online experiment, allow scientists to perform more easily studies that include multicultural samples. It is important to promote these practices, encouraging researchers of different nations and backgrounds to collaborate. Old debates, such as that related to the influence of language and languages on cognition, have acquired a new fresh status. A mature reflection on these topics is important and crucial for the development of our discipline. Cross-cultural research should be promoted and fostered.

- Dear old themes . Some topics are crucial for the understanding of mind, brain, behavior. Unluckily debates on some apparently old-fashioned topics are sometimes abandoned, but focusing on them can offer new insights and open new research venues. A strong theoretical and philosophical approach, firmly based on scientific evidence, can offer fresh perspectives and exciting new ideas on these topics. Some examples include the nature-nurture debate; the role of notions such as simulation and representation for psychological understanding; the mechanisms underlying the ability of abstraction/abstractness in animal and human cognition; how concepts are acquired and represented in the brain; the effects of language on perception, categorization, and thought; our sense of body; the theories of narrative self; the role of interoceptive and emotional experience, of religious experience, of mindfulness; penetrability of cognition/perception; how consciousness work; the mechanisms underlying the formation of beliefs and their influence on decision making; how we represent others, e.g., through stereotypes and implicit biases, comprehend them, e.g., through mindreading and perspective taking, and act with them, e.g., through joint action; how we represent morality, social norms, and institutions.

To conclude: How do we dream the psychology of the future? First, we dream of a psychology focusing on theoretically solid, explanation-based accounts, and on the identification of key principles rather than on fashionable effects. Second, we dream of a psychology open to diversity,-characterized by an interdisciplinary approach, and more open to methodological contaminations and to the possibility to perform studies on different populations.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Fausto Caruana, Felice Cimatti, Federico DaRold, and Luca Tummolini for suggestions, discussions, and comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

- Barrett L. F. (2017). How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain . New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barsalou L. W. (1999). Perceptions of perceptual symbols . Behav. Brain Sci. 22 , 637–660. 10.1017/S0140525X99532147 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caligiore D., Borghi A. M., Parisi D., Baldassarre G. (2010). TRoPICALS: a computational embodied neuroscience model of compatibility effects . Psychol. Rev. 117 , 1188–228. 10.1037/a0020887 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cummins R. (2000). How does it work? “versus” what are the laws?": two conceptions of psychological explanation,” in Explanation and Cognition , eds Keil F., Wilson Robert A. (Cambridge: MIT Press; ), 117–144. [ Google Scholar ]

- Henrich J., Heine S. J., Norenzayan A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33 , 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hommel B., Colzato L. S. (2017). The grand challenge: integrating nomothetic and ideographic approaches to human cognition . Front. Psychol. 8 :100. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00100 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hruschka D. J., Medin D. L., Rogoff B., Henrich J. (2018). Pressing questions in the study of psychological and behavioral diversity . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 , 11366–11368. 10.1073/pnas.1814733115 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pezzulo G., Barsalou L. W., Cangelosi A., Fischer M. H., Spivey M., McRae K. (2011). The mechanics of embodiment: a dialog on embodiment and computational modeling . Front. Psychol. 2 :5. 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00005 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prinz J. J. (2012). Beyond Human Nature: How Culture and Experience Shape Our Lives . London: Penguin. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Rooij I. (2018). Available online at: https://featuredcontent.psychonomic.org/psychological-science-needs-theory-development-before-preregistration/ (accessed January 18, 2018).

Science of Psychology

The Go-To Science

Curiosity is part of human nature. One of the first questions children learn to ask is “why?” As adults, we continue to wonder. Using empirical methods, psychologists apply that universal curiosity to collect and interpret research data to better understand and solve some of society’s most challenging problems.

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to think of a facet of life where psychology is not involved. Psychologists employ the scientific method — stating the question, offering a theory and then constructing rigorous laboratory or field experiments to test the hypothesis. Psychologists apply the understanding gleaned through research to create evidence-based strategies that solve problems and improve lives.

The result is that psychological science unveils new and better ways for people to exist and thrive in a complex world.

Psychologists in Action

Helping Businesses

Dr. Jack Stark uses psychological science to help NASCAR drivers achieve optimal performance and keep their team in the winner’s circle.

Improving Lives

Dr. David Strayer uses psychological science to study distracted driving by putting people through rigorous concentration tests during driving simulations.

Promoting Health

Dr. Deborah Tate uses psychological science to identify strategies for improving weight loss . Her research brings the proven benefits of face-to-face weight loss programs to more people through technology.

Helping Organizations

As an organizational psychologist, Dr. Eduardo Salas studies people where they work — examining what they do and how they make decisions.

Working in Schools

Dr. Kathleen Kremer knows a thing or two about fun. Using psychological science, she studies user attitudes, behaviors and emotions to learn what makes a child love a toy.

Science in Action

Psychology is a varied field. Psychologists conduct basic and applied research, serve as consultants to communities and organizations, diagnose and treat people, and teach future psychologists and those who will pursue other disciplines. They test intelligence and personality.

Many psychologists work as health care providers. They assess behavioral and mental function and well-being. Other psychologists study how human beings relate to each other and to machines, and work to improve these relationships.

The application of psychological research can decrease the economic burden of disease on government and society as people learn how to make choices that improve their health and well-being. The strides made in educational assessments are helping students with learning disabilities. Psychological science helps educators understand how children think, process and remember — helping to design effective teaching methods. Psychological science contributes to justice by helping the courts understand the minds of criminals, evidence and the limits of certain types of evidence or testimony.

The science of psychology is pervasive. Psychologists work in some of the nation’s most prominent companies and organizations. From Google, Boeing and NASA to the federal government, national health care organizations and research groups to Cirque du Soleil, Disney and NASCAR — psychologists are there, playing important roles.

Brain science and cognitive psychology

Climate and environmental psychology

Clinical psychology

Counseling psychology

Developmental psychology

Experimental psychology

Forensic and public service psychology

Health psychology

Human factors and engineering psychology

Industrial and organizational psychology

Psychology of teaching and learning

Quantitative psychology

Rehabilitation psychology

Social psychology

Sport and performance psychology

Psychology Careers: What to Know

Why the reliance on data? Findings and statistics from research studies can impact us emotionally, add credibility to an article, and ground us in the real world. However, the importance of research findings reaches far beyond providing knowledge to the general population. Research and evaluation studies — those studies that assess a program’s impact — are integral to promoting mental health and reducing the burden of mental illness in different populations.

Mental health research identifies biopsychosocial factors — how biological, psychological and social functioning are interacting — detecting trends and social determinants in population health. That data greatly informs the current state of mental health in the U.S. and around the world. Findings from such studies also influence fields such as public health, health care and education. For example, mental health research and evaluation can impact public health policies by assisting public health professionals in strategizing policies to improve population mental health.

Research helps us understand how to best promote mental health in different populations. From its definition to how it discussed, mental health is seen differently in every community. Thus, mental health research and evaluation not only reveals mental health trends but also informs us about how to best promote mental health in different racial and ethnic populations. What does mental health look like in this community? Is there stigma associated with mental health challenges? How do individuals in the community view those with mental illness? These are the types of questions mental health research can answer.

Data aids us in understanding whether the mental health services and resources that are available meet mental health needs. Many times the communities where needs are the greatest are the ones where there are limited services and resources available. Mental health research and evaluation informs public health professionals and other relevant stakeholders of the gaps that currently exist so they can prioritize policies and strategies for communities where gaps are the greatest.

Research establishes evidence for the effectiveness of public health policies and programs. Mental health research and evaluation help develop evidence for the effectiveness of healthcare policies and strategies as well as mental health promotion programs. This evidence is crucial for showcasing the value and return on investment for programs and policies, which can justify local, state and federal expenditures. For example, mental health research studies evaluating the impact of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) have revealed that individuals taking the course show increases in knowledge about mental health, greater confidence to assist others in distress, and improvements in their own mental wellbeing. They have been fundamental in assisting organizations and instructors in securing grant funding to bring MHFA to their communities.

The findings from mental health research and evaluation studies provide crucial information about the specific needs within communities and the impacts of public education programs like MHFA. These studies provide guidance on how best to improve mental health in different contexts and ensure financial investments go towards programs proven to improve population mental health and reduce the burden of mental illness in the U.S.

In 2021, in a reaffirmation of its dedication and commitment to mental health and substance use research and community impact, Mental Health First Aid USA introduced MHFA Research Advisors. The group advises and assists Mental Health First Aid USA on ongoing research and future opportunities related to individual MHFA programs, including Youth MHFA, teen MHFA and MHFA at Work.