Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

Published on January 27, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

A semi-structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions within a predetermined thematic framework. However, the questions are not set in order or in phrasing.

In research, semi-structured interviews are often qualitative in nature. They are generally used as an exploratory tool in marketing, social science, survey methodology, and other research fields.

They are also common in field research with many interviewers, giving everyone the same theoretical framework, but allowing them to investigate different facets of the research question .

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

Table of contents

What is a semi-structured interview, when to use a semi-structured interview, advantages of semi-structured interviews, disadvantages of semi-structured interviews, semi-structured interview questions, how to conduct a semi-structured interview, how to analyze a semi-structured interview, presenting your results (with example), other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about semi-structured interviews.

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews.

- Unlike in an unstructured interview, the interviewer has an idea of what questions they will ask.

- Unlike in a structured interview, the phrasing and order of the questions is not set.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility. Asking set questions in a set order allows for easy comparison between respondents, but it can be limiting. Having less structure can help you see patterns, while still allowing for comparisons between respondents.

Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uneasy.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. Participant answers can guide future research questions and help you develop a more robust knowledge base for future research.

Just like in structured interviews, it is critical that you remain organized and develop a system for keeping track of participant responses. However, since the questions are less set than in a structured interview, the data collection and analysis become a bit more complex.

Differences between different types of interviews

Make sure to choose the type of interview that suits your research best. This table shows the most important differences between the four types.

| Fixed questions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed order of questions | ||||

| Fixed number of questions | ||||

| Option to ask additional questions |

Semi-structured interviews come with many advantages.

Best of both worlds

No distractions, detail and richness.

However, semi-structured interviews also have their downsides.

Low validity

High risk of research bias, difficult to develop good semi-structured interview questions.

Since they are often open-ended in style, it can be challenging to write semi-structured interview questions that get you the information you’re looking for without biasing your responses. Here are a few tips:

- Define what areas or topics you will be focusing on prior to the interview. This will help you write a framework of questions that zero in on the information you seek.

- Write yourself a guide to refer to during the interview, so you stay focused. It can help to start with the simpler questions first, moving into the more complex ones after you have established a comfortable rapport.

- Be as clear and concise as possible, avoiding jargon and compound sentences.

- How often per week do you go to the gym? a) 1 time; b) 2 times; c) 3 times; d) 4 or more times

- If yes: What feelings does going to the gym bring out in you?

- If no: What do you prefer to do instead?

- If yes: How did this membership affect your job performance? Did you stay longer in the role than you would have if there were no membership?

Once you’ve determined that a semi-structured interview is the right fit for your research topic , you can proceed with the following steps.

Step 1: Set your goals and objectives

You can use guiding questions as you conceptualize your research question, such as:

- What are you trying to learn or achieve from a semi-structured interview?

- Why are you choosing a semi-structured interview as opposed to a different type of interview, or another research method?

If you want to proceed with a semi-structured interview, you can start designing your questions.

Step 2: Design your questions

Try to stay simple and concise, and phrase your questions clearly. If your topic is sensitive or could cause an emotional response, be mindful of your word choices.

One of the most challenging parts of a semi-structured interview is knowing when to ask follow-up or spontaneous related questions. For this reason, having a guide to refer back to is critical. Hypothesizing what other questions could arise from your participants’ answers may also be helpful.

Step 3: Assemble your participants

There are a few sampling methods you can use to recruit your interview participants, such as:

- Voluntary response sampling : For example, sending an email to a campus mailing list and sourcing participants from responses.

- Stratified sampling of a particular characteristic trait of interest to your research, such as age, race, ethnicity, or gender identity.

Step 4: Decide on your medium

It’s important to determine ahead of time how you will be conducting your interview. You should decide whether you’ll be conducting it live or with a pen-and-paper format. If conducted in real time, you also need to decide if in person, over the phone, or via videoconferencing is the best option for you.

Note that each of these methods has its own advantages and disadvantages:

- Pen-and-paper may be easier for you to organize and analyze, but you will receive more prepared answers, which may affect the reliability of your data.

- In-person interviews can lead to nervousness or interviewer effects, where the respondent feels pressured to respond in a manner they believe will please you or incentivize you to like them.

Step 5: Conduct your interviews

As you conduct your interviews, keep environmental conditions as constant as you can to avoid bias. Pay attention to your body language (e.g., nodding, raising eyebrows), and moderate your tone of voice.

Relatedly, one of the biggest challenges with semi-structured interviews is ensuring that your questions remain unbiased. This can be especially challenging with any spontaneous questions or unscripted follow-ups that you ask your participants.

After you’re finished conducting your interviews, it’s time to analyze your results. First, assign each of your participants a number or pseudonym for organizational purposes.

The next step in your analysis is to transcribe the audio or video recordings. You can then conduct a content or thematic analysis to determine your categories, looking for patterns of responses that stand out to you and test your hypotheses .

Transcribing interviews

Before you get started with transcription, decide whether to conduct verbatim transcription or intelligent verbatim transcription.

- If pauses, laughter, or filler words like “umm” or “like” affect your analysis and research conclusions, conduct verbatim transcription and include them.

- If not, you can conduct intelligent verbatim transcription, which excludes fillers, fixes any grammatical issues, and is usually easier to analyze.

Transcribing presents a great opportunity for you to cleanse your data . Here, you can identify and address any inconsistencies or questions that come up as you listen.

Your supervisor might ask you to add the transcriptions to the appendix of your paper.

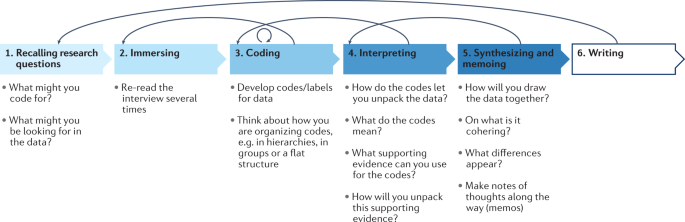

Coding semi-structured interviews

Next, it’s time to conduct your thematic or content analysis . This often involves “coding” words, patterns, or recurring responses, separating them into labels or categories for more robust analysis.

Due to the open-ended nature of many semi-structured interviews, you will most likely be conducting thematic analysis, rather than content analysis.

- You closely examine your data to identify common topics, ideas, or patterns. This can help you draw preliminary conclusions about your participants’ views, knowledge or experiences.

- After you have been through your responses a few times, you can collect the data into groups identified by their “code.” These codes give you a condensed overview of the main points and patterns identified by your data.

- Next, it’s time to organize these codes into themes. Themes are generally broader than codes, and you’ll often combine a few codes under one theme. After identifying your themes, make sure that these themes appropriately represent patterns in responses.

Analyzing semi-structured interviews

Once you’re confident in your themes, you can take either an inductive or a deductive approach.

- An inductive approach is more open-ended, allowing your data to determine your themes.

- A deductive approach is the opposite. It involves investigating whether your data confirm preconceived themes or ideas.

After your data analysis, the next step is to report your findings in a research paper .

- Your methodology section describes how you collected the data (in this case, describing your semi-structured interview process) and explains how you justify or conceptualize your analysis.

- Your discussion and results sections usually address each of your coded categories.

- You can then conclude with the main takeaways and avenues for further research.

Example of interview methodology for a research paper

Let’s say you are interested in vegan students on your campus. You have noticed that the number of vegan students seems to have increased since your first year, and you are curious what caused this shift.

You identify a few potential options based on literature:

- Perceptions about personal health or the perceived “healthiness” of a vegan diet

- Concerns about animal welfare and the meat industry

- Increased climate awareness, especially in regards to animal products

- Availability of more vegan options, making the lifestyle change easier

Anecdotally, you hypothesize that students are more aware of the impact of animal products on the ongoing climate crisis, and this has influenced many to go vegan. However, you cannot rule out the possibility of the other options, such as the new vegan bar in the dining hall.

Since your topic is exploratory in nature and you have a lot of experience conducting interviews in your work-study role as a research assistant, you decide to conduct semi-structured interviews.

You have a friend who is a member of a campus club for vegans and vegetarians, so you send a message to the club to ask for volunteers. You also spend some time at the campus dining hall, approaching students at the vegan bar asking if they’d like to participate.

Here are some questions you could ask:

- Do you find vegan options on campus to be: excellent; good; fair; average; poor?

- How long have you been a vegan?

- Follow-up questions can probe the strength of this decision (i.e., was it overwhelmingly one reason, or more of a mix?)

Depending on your participants’ answers to these questions, ask follow-ups as needed for clarification, further information, or elaboration.

- Do you think consuming animal products contributes to climate change? → The phrasing implies that you, the interviewer, do think so. This could bias your respondents, incentivizing them to answer affirmatively as well.

- What do you think is the biggest effect of animal product consumption? → This phrasing ensures the participant is giving their own opinion, and may even yield some surprising responses that enrich your analysis.

After conducting your interviews and transcribing your data, you can then conduct thematic analysis, coding responses into different categories. Since you began your research with several theories about campus veganism that you found equally compelling, you would use the inductive approach.

Once you’ve identified themes and patterns from your data, you can draw inferences and conclusions. Your results section usually addresses each theme or pattern you found, describing each in turn, as well as how often you came across them in your analysis. Feel free to include lots of (properly anonymized) examples from the data as evidence, too.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A semi-structured interview is a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews. Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uncomfortable.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favorably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behavior accordingly.

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach, while deductive reasoning is top-down.

Inductive reasoning takes you from the specific to the general, while in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/semi-structured-interview/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, structured interview | definition, guide & examples, unstructured interview | definition, guide & examples, what is a focus group | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- What is a semi-structured interview?

Last updated

5 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

When designed correctly, user interviews go much deeper than surface-level survey responses. They can provide new information about how people interact with your products and services, and shed light on the underlying reasons behind these habits.

Semi-structured user interviews are widely considered one of the most effective tools for doing this kind of qualitative research , depending on your specific goals. As the name suggests, the semi-structured format allows for a more natural, conversational flow, while still being organized enough to collect plenty of actionable data .

Analyze semi-structured interviews

Bring all your semi-structured interviews into one place to analyze and understand

A semi-structured interview is a qualitative research method used to gain an in-depth understanding of the respondent's feelings and beliefs on specific topics. As the interviewer prepares the questions ahead of time, they can adjust the order, skip any that are redundant, or create new ones. Additionally, the interviewer should be prepared to ask follow-up questions and probe for more detail.

Semi-structured interviews typically last between 30 and 60 minutes and are usually conducted either in person or via a video call. Ideally, the interviewer can observe the participant's verbal and non-verbal cues in real-time, allowing them to adjust their approach accordingly. The interviewer aims for a conversational flow that helps the participant talk openly while still focusing on the primary topics being researched.

Once the interview is over, the researcher analyzes the data in detail to draw meaningful results. This involves sorting the data into categories and looking for patterns and trends. This semi-structured interview approach provides an ideal framework for obtaining open-ended data and insights.

- When to use a semi-structured interview?

Semi-structured interviews are considered the "best of both worlds" as they tap into the strengths of structured and unstructured methods. Researchers can gather reliable data while also getting unexpected insights from in-depth user feedback.

Semi-structured interviews can be useful during any stage of the UX product-development process, including exploratory research to better understand a new market or service. Further down the line, this approach is ideal for refining existing designs and discovering areas for improvement. Semi-structured interviews can even be the first step when planning future research projects using another method of data collection.

- Advantages of semi-structured interviews

Flexibility

This style of interview is meant to be adapted according to the answers and reactions of the respondent, which gives a lot of flexibility. Semi-structured interviews encourage two-way communication, allowing themes and ideas to emerge organically.

Respondent comfort

The semi-structured format feels more natural and casual for participants than a formal interview. This can help to build rapport and more meaningful dialogue.

Semi-structured interviews are excellent for user experience research because they provide rich, qualitative data about how people really experience your products and services.

Open-ended questions allow the respondent to provide nuanced answers, with the potential for more valuable insights than other forms of data collection, like structured interviews , surveys , or questionnaires.

- Disadvantages of semi-structured interviews

Can be unpredictable

Less structure brings less control, especially if the respondent goes off tangent or doesn't provide useful information. If the conversation derails, it can take a lot of effort to bring the focus back to the relevant topics.

Lack of standardization

Every semi-structured interview is unique, including potentially different questions, so the responses collected are very subjective. This can make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions from the data unless your team invests the time in a comprehensive analysis.

Compared to other research methods, unstructured interviews are not as consistent or "ready to use."

- Best practices when preparing for a semi-structured interview

While semi-structured interviews provide a lot of flexibility, they still require thoughtful planning. Maximizing the potential of this research method will depend on having clear goals that help you narrow the focus of the interviews and keep each session on track.

After taking the time to specify these parameters, create an interview guide to serve as a framework for each conversation. This involves crafting a range of questions that can explore the necessary themes and steer the conversation in the right direction. Everything in your interview guide is optional (that's the beauty of being "semi" structured), but it's still an essential tool to help the conversation flow and collect useful data.

Best practices to consider while designing your interview questions include:

Prioritize open-ended questions

Promote a more interactive, meaningful dialogue by avoiding questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no, otherwise known as close-ended questions.

Stick with "what," "when," "who," "where," "why," and "how" questions, which allow the participant to go beyond the superficial to express their ideas and opinions. This approach also helps avoid jargon and needless complexity in your questions.

Open-ended questions help the interviewer uncover richer, qualitative details, which they can build on to get even more valuable insights.

Plan some follow-up questions

When preparing questions for the interview guide, consider the responses you're likely to get and pair them up with some effective, relevant follow-up questions. Factual questions should be followed by ones that ask an opinion.

Planning potential follow-up questions will help you to get the most out of a semi-structured interview. They allow you to delve deeper into the participant's responses or hone in on the most important themes of your research focus.

Follow-up questions are also invaluable when the interviewer feels stuck and needs a meaningful prompt to continue the conversation.

Avoid leading questions

Leading questions are framed toward a predetermined answer. This makes them likely to result in data that is biased, inaccurate, or otherwise unreliable.

For example, asking "Why do you think our services are a good solution?" or "How satisfied have you been with our services?" will leave the interviewee feeling pressured to agree with some baseline assumptions.

Interviewers must take the time to evaluate their questions and make a conscious effort to remove any potential bias that could get in the way of authentic feedback.

Asking neutral questions is key to encouraging honest responses in a semi-structured interview. For example, "What do you consider to be the advantages of using our services?" or simply "What has been your experience with using our services?"

Neutral questions are effective in capturing a broader range of opinions than closed questions, which is ultimately one of the biggest benefits of using semi-structured interviews for research.

Use the critical incident method

The critical incident method is an approach to interviewing that focuses on the past behavior of respondents, as opposed to hypothetical scenarios. One of the challenges of all interview research methods is that people are not great at accurately recalling past experiences, or answering future-facing, abstract questions.

The critical incident method helps avoid these limitations by asking participants to recall extreme situations or 'critical incidents' which stand out in their memory as either particularly positive or negative. Extreme situations are more vivid so they can be recalled more accurately, potentially providing more meaningful insights into the interviewee’s experience with your products or services.

- Best practices while conducting semi-structured interviews

Encouraging interaction is the key to collecting more specific data than is typically possible during a formal interview. Facilitating an effective semi-structured interview is a balancing act between asking prepared questions and creating the space for organic conversation. Here are some guidelines for striking the right tone.

Beginning the interview

Make participants feel comfortable by introducing yourself and your role at the organization and displaying appropriate body language.

Outline the purpose of the interview to give them an idea of what to expect. For example, explain that you want to learn more about how people use your product or service.

It's also important to thank them for their time in advance and emphasize there are no right or wrong answers.

Practice active listening

Build trust and rapport throughout the interview with active listening techniques, focusing on being present and demonstrating that you're paying attention by responding thoughtfully. Engage with the participant by making eye contact, nodding, and giving verbal cues like "Okay, I see," "I understand," and "M-hm."

Avoid the temptation to rush to fill any silences while they're in the middle of responding, even if it feels awkward. Give them time to finish their train of thought before interrupting with feedback or another prompt. Embracing these silences is essential for active listening because it's a sign of a productive interview with meaningful, candid responses.

Practicing these techniques will ensure the respondent feels heard and respected, which is critical for gathering high-quality information.

Ask clarifying questions in real time

In a semi-structured interview, the researcher should always be on the lookout for opportunities to probe into the participant's thoughts and opinions.

Along with preparing follow-up questions, get in the habit of asking clarifying questions whenever possible. Clarifying questions are especially important for user interviews because people often provide vague responses when discussing how they interact with products and services.

Being asked to go deeper will encourage them to give more detail and show them you’re taking their opinions seriously and are genuinely interested in understanding their experiences.

Some clarifying questions that can be asked in real-time include:

"That's interesting. Could you give me some examples of X?"

"What do you mean when you say "X"?"

"Why is that?"

"It sounds like you're saying [rephrase their response], is that correct?"

Minimize note-taking

In a wide-ranging conversation, it's easy to miss out on potentially valuable insights by not staying focused on the user. This is why semi-structured interviews are generally recorded (audio or video), and it's common to have a second researcher present to take notes.

The person conducting the interview should avoid taking notes because it's a distraction from:

Keeping track of the conversation

Engaging with the user

Asking thought-provoking questions

Watching you take notes can also have the unintended effect of making the participant feel pressured to give shallower, shorter responses—the opposite of what you want.

Concluding the interview

Semi-structured interviews don't come with a set number of questions, so it can be tricky to bring them to an end. Give the participant a sense of closure by asking whether they have anything to add before wrapping up, or if they want to ask you any questions, and then give sincere thanks for providing honest feedback.

Don't stop abruptly once all the relevant topics have been discussed or you're nearing the end of the time that was set aside. Make them feel appreciated!

- Analyzing the data from semi-structured interviews

In some ways, the real work of semi-structured interviews begins after all the conversations are over, and it's time to analyze the data you've collected. This process will focus on sorting and coding each interview to identify patterns, often using a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods.

Some of the strategies for making sense of semi-structured interviews include:

Thematic analysis : focuses on the content of the interviews and identifying common themes

Discourse analysis : looks at how people express feelings about themes such as those involving politics, culture, and power

Qualitative data mapping: a visual way to map out the correlations between different elements of the data

Narrative analysis : uses stories and language to unlock perspectives on an issue

Grounded theory : can be applied when there is no existing theory that could explain a new phenomenon

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Fam Med Community Health

- v.7(2); 2019

Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour

Melissa dejonckheere.

1 Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Lisa M Vaughn

2 Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

3 Division of Emergency Medicine, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Associated Data

fmch-2018-000057supp001.pdf

Semistructured in-depth interviews are commonly used in qualitative research and are the most frequent qualitative data source in health services research. This method typically consists of a dialogue between researcher and participant, guided by a flexible interview protocol and supplemented by follow-up questions, probes and comments. The method allows the researcher to collect open-ended data, to explore participant thoughts, feelings and beliefs about a particular topic and to delve deeply into personal and sometimes sensitive issues. The purpose of this article was to identify and describe the essential skills to designing and conducting semistructured interviews in family medicine and primary care research settings. We reviewed the literature on semistructured interviewing to identify key skills and components for using this method in family medicine and primary care research settings. Overall, semistructured interviewing requires both a relational focus and practice in the skills of facilitation. Skills include: (1) determining the purpose and scope of the study; (2) identifying participants; (3) considering ethical issues; (4) planning logistical aspects; (5) developing the interview guide; (6) establishing trust and rapport; (7) conducting the interview; (8) memoing and reflection; (9) analysing the data; (10) demonstrating the trustworthiness of the research; and (11) presenting findings in a paper or report. Semistructured interviews provide an effective and feasible research method for family physicians to conduct in primary care research settings. Researchers using semistructured interviews for data collection should take on a relational focus and consider the skills of interviewing to ensure quality. Semistructured interviewing can be a powerful tool for family physicians, primary care providers and other health services researchers to use to understand the thoughts, beliefs and experiences of individuals. Despite the utility, semistructured interviews can be intimidating and challenging for researchers not familiar with qualitative approaches. In order to elucidate this method, we provide practical guidance for researchers, including novice researchers and those with few resources, to use semistructured interviewing as a data collection strategy. We provide recommendations for the essential steps to follow in order to best implement semistructured interviews in family medicine and primary care research settings.

Introduction

Semistructured interviews can be used by family medicine researchers in clinical settings or academic settings even with few resources. In contrast to large-scale epidemiological studies, or even surveys, a family medicine researcher can conduct a highly meaningful project with interviews with as few as 8–12 participants. For example, Chang and her colleagues, all family physicians, conducted semistructured interviews with 10 providers to understand their perspectives on weight gain in pregnant patients. 1 The interviewers asked questions about providers’ overall perceptions on weight gain, their clinical approach to weight gain during pregnancy and challenges when managing weight gain among pregnant patients. Additional examples conducted by or with family physicians or in primary care settings are summarised in table 1 . 1–6

Examples of research articles using semistructured interviews in primary care research

| Article | Study purpose | Context/setting | Use of interviews |

| Chang T, Llanes M, Gold KJ, . Perspectives about and approaches to weight gain in pregnancy: a qualitative study of physicians and nurse midwives. 2013;13:47. | To explore prenatal care providers’ perspectives on patient weight gain during pregnancy | University hospital in the USA | 10 semistructured interviews with prenatal care providers (family physicians, obstetricians, nurse midwives); thematic analysis |

| Croxson CH, Ashdown HF, Hobbs FR. GPs’ perceptions of workload in England: a qualitative interview study. 2017. | To understand perceptions of provider workload | NHS in England | 34 semistructured interviews with general practitioners; thematic analysis |

| DeJonckheere M, Robinson CH, Evans L, Designing for clinical change: creating an intervention to implement new statin guidelines in a primary care clinic. 2018;5 . | To elicit provider perspectives of their uptake of new statin guidelines. To tailor a local quality improvement intervention to improve statin prescribing. | Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the USA | 15 semistructured interviews with providers (primary care physicians and clinical pharmacists); deductive thematic analysis |

| Griffiths F, Lowe P, Boardman F, . Becoming pregnant: exploring the perspectives of women living with diabetes. 2008;58:184–90 . | To explore women's accounts of their journeys to becoming pregnant while living with type 1 diabetes | Four UK specialist diabetes antenatal clinics | 15 semistructured interviews with women with pregestational type 1 diabetes; thematic analysis |

| Saigal P, Takemura Y, Nishiue T, Factors considered by medical students when formulating their specialty preferences in Japan: findings from a qualitative study 7:31, 2007. | To understand factors considered by Japanese medical students when choosing their specialty | Medical school in Japan | 25 semistructured interviews with medical students, informal interviews with academic faculty, field notes; thematic analysis |

| Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, . Older adults’ preferences for when and how to discuss life expectancy in primary care. 2017;30:813–5. | To elucidate perspectives on how and when to discuss life expectancy with older adults | Four clinical programmes affiliated with an urban academic medical centre | 40 semistructured interviews with community-dwelling older adults; qualitative content analysis |

From our perspective as seasoned qualitative researchers, conducting effective semistructured interviews requires: (1) a relational focus, including active engagement and curiosity, and (2) practice in the skills of interviewing. First, a relational focus emphasises the unique relationship between interviewer and interviewee. To obtain quality data, interviews should not be conducted with a transactional question-answer approach but rather should be unfolding, iterative interactions between the interviewer and interviewee. Second, interview skills can be learnt. Some of us will naturally be more comfortable and skilful at conducting interviews but all aspects of interviews are learnable and through practice and feedback will improve. Throughout this article, we highlight strategies to balance relationship and rigour when conducting semistructured interviews in primary care and the healthcare setting.

Qualitative research interviews are ‘attempts to understand the world from the subjects’ point of view, to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations’ (p 1). 7 Qualitative research interviews unfold as an interviewer asks questions of the interviewee in order to gather subjective information about a particular topic or experience. Though the definitions and purposes of qualitative research interviews vary slightly in the literature, there is common emphasis on the experiences of interviewees and the ways in which the interviewee perceives the world (see table 2 for summary of definitions from seminal texts).

Definitions of qualitative interviews

| Authors | Definition | Purpose |

| DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree | Semistructured interviews are ‘organized around a set of predetermined open-ended questions, with other questions emerging from the dialogue between interviewer and interviewee/s’ (2006, p 315) | ‘To contribute to a body of knowledge that is conceptual and theoretical and is based on the meanings that life experiences hold for the interviewees’ (2006, p 314) |

| Hatch | ‘special kinds of conversations or speech events that are used by researchers to explore informants’ experiences and interpretations’ (2002, p. 91) | ‘To uncover the meaning structures that participants use to organize their experiences and make sense of their worlds’ (2002, p 91) |

| Kvale | ‘attempts to understand the world from the subjects' point of view, to unfold the meaning of peoples' experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations’ (1996, p 1) | ‘To gather descriptions of the life-world of the interviewee with respect to interpretation of the meaning of the described phenomena’ (1983, p 174) |

| Josselson | ‘a shared product of two people—one the interviewer, the other the interviewee—talk about and they talk together’ (2013, p 1) | ‘To enter the world of the participant and try to understand how it looks and feels from the participant’s point of view’ (2013, p 80) |

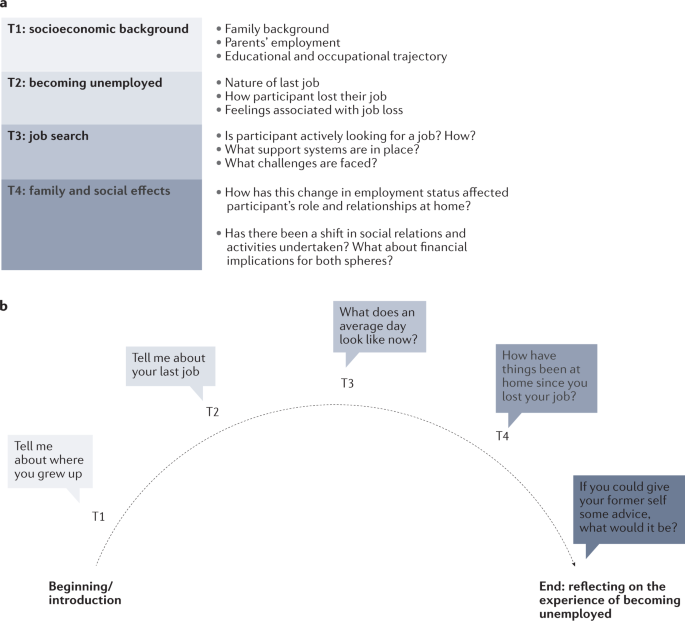

The most common type of interview used in qualitative research and the healthcare context is semistructured interview. 8 Figure 1 highlights the key features of this data collection method, which is guided by a list of topics or questions with follow-up questions, probes and comments. Typically, the sequencing and wording of the questions are modified by the interviewer to best fit the interviewee and interview context. Semistructured interviews can be conducted in multiple ways (ie, face to face, telephone, text/email, individual, group, brief, in-depth), each of which have advantages and disadvantages. We will focus on the most common form of semistructured interviews within qualitative research—individual, face-to-face, in-depth interviews.

Key characteristics of semistructured interviews.

Purpose of semistructured interviews

The overall purpose of using semistructured interviews for data collection is to gather information from key informants who have personal experiences, attitudes, perceptions and beliefs related to the topic of interest. Researchers can use semistructured interviews to collect new, exploratory data related to a research topic, triangulate other data sources or validate findings through member checking (respondent feedback about research results). 9 If using a mixed methods approach, semistructured interviews can also be used in a qualitative phase to explore new concepts to generate hypotheses or explain results from a quantitative phase that tests hypotheses. Semistructured interviews are an effective method for data collection when the researcher wants: (1) to collect qualitative, open-ended data; (2) to explore participant thoughts, feelings and beliefs about a particular topic; and (3) to delve deeply into personal and sometimes sensitive issues.

Designing and conducting semistructured interviews

In the following section, we provide recommendations for the steps required to carefully design and conduct semistructured interviews with emphasis on applications in family medicine and primary care research (see table 3 ).

Steps to designing and conducting semistructured interviews

| Step | Task |

| 1 | Determining the purpose and scope of the study |

| 2 | Identifying participants |

| 3 | Considering ethical issues |

| 4 | Planning logistical aspects |

| 5 | Developing the interview guide |

| 6 | Establishing trust and rapport |

| 7 | Conducting the interview |

| 8 | Memoing and reflection |

| 9 | Analysing the data |

| 10 | Demonstrating the trustworthiness of the research |

| 11 | Presenting findings in a paper or report |

Steps for designing and conducting semistructured interviews

Step 1: determining the purpose and scope of the study.

The purpose of the study is the primary objective of your project and may be based on an anecdotal experience, a review of the literature or previous research finding. The purpose is developed in response to an identified gap or problem that needs to be addressed.

Research questions are the driving force of a study because they are associated with every other aspect of the design. They should be succinct and clearly indicate that you are using a qualitative approach. Qualitative research questions typically start with ‘What’, ‘How’ or ‘Why’ and focus on the exploration of a single concept based on participant perspectives. 10

Step 2: identifying participants

After deciding on the purpose of the study and research question(s), the next step is to determine who will provide the best information to answer the research question. Good interviewees are those who are available, willing to be interviewed and have lived experiences and knowledge about the topic of interest. 11 12 Working with gatekeepers or informants to get access to potential participants can be extremely helpful as they are trusted sources that control access to the target sample.

Sampling strategies are influenced by the research question and the purpose of the study. Unlike quantitative studies, statistical representativeness is not the goal of qualitative research. There is no calculation of statistical power and the goal is not a large sample size. Instead, qualitative approaches seek an in-depth and detailed understanding and typically use purposeful sampling. See the study of Hatch for a summary of various types of purposeful sampling that can be used for interview studies. 12

‘How many participants are needed?’ The most common answer is, ‘it depends’—it depends on the purpose of the study, what kind of study is planned and what questions the study is trying to answer. 12–14 One common standard in qualitative sample sizes is reaching thematic saturation, which refers to the point at which no new thematic information is gathered from participants. Malterud and colleagues discuss the concept of information power , or a qualitative equivalent to statistical power, to determine how many interviews should be collected in a study. They suggest that the size of a sample should depend on the aim, homogeneity of the sample, theory, interview quality and analytic strategy. 14

Step 3: considering ethical issues

An ethical attitude should be present from the very beginning of the research project even before you decide who to interview. 15 This ethical attitude should incorporate respect, sensitivity and tact towards participants throughout the research process. Because semistructured interviewing often requires the participant to reveal sensitive and personal information directly to the interviewer, it is important to consider the power imbalance between the researcher and the participant. In healthcare settings, the interviewer or researcher may be a part of the patient’s healthcare team or have contact with the healthcare team. The researchers should ensure the interviewee that their participation and answers will not influence the care they receive or their relationship with their providers. Other issues to consider include: reducing the risk of harm; protecting the interviewee’s information; adequately informing interviewees about the study purpose and format; and reducing the risk of exploitation. 10

Step 4: planning logistical aspects

Careful planning particularly around the technical aspects of interviews can be the difference between a great interview and a not so great interview. During the preparation phase, the researcher will need to plan and make decisions about the best ways to contact potential interviewees, obtain informed consent, arrange interview times and locations convenient for both participant and researcher, and test recording equipment. Although many experienced researchers have found themselves conducting interviews in less than ideal locations, the interview location should avoid (or at least minimise) interruptions and be appropriate for the interview (quiet, private and able to get a clear recording). 16 For some research projects, the participants’ homes may make sense as the best interview location. 16

Initial contacts can be made through telephone or email and followed up with more details so the individual can make an informed decision about whether they wish to be interviewed. Potential participants should know what to expect in terms of length of time, purpose of the study, why they have been selected and who will be there. In addition, participants should be informed that they can refuse to answer questions or can withdraw from the study at any time, including during the interview itself.

Audio recording the interview is recommended so that the interviewer can concentrate on the interview and build rapport rather than being distracted with extensive note taking 16 (see table 4 for audio-recording tips). Participants should be informed that audio recording is used for data collection and that they can refuse to be audio recorded should they prefer.

Suggestions for successful audio recording of interviews

| Component | Suggestions |

| Clarity | Audio-recording equipment should clearly capture the interview so that both interviewer’s and interviewee’s voices are easily heard for transcription. Many interviewers use small battery-powered recorders but sometimes the microphones do not work well. |

| Reliable | Audio-recording equipment needs to be reliable and easy to use. Increasingly, researchers are using their smartphones to record interviews. |

| Familiarity | Whatever kind of recording equipment is used, the researcher needs to be familiar with it and should test it at the interview location before starting the actual interview—you do not want to be fumbling with technology during the interview. |

| Backup | If you are the sole interviewer and do not have an additional person taking notes, we recommend having two recording devices for each interview in case one device fails or runs out of batteries. Make sure to bring extra batteries. |

| Note-taking | Some researchers recommend taking notes or having a partner take notes during the interviews in addition to the audio recording. Taking notes can ensure that all interview questions have been answered, guide follow-up questions so that the interview can flow from the interviewee’s lead and serve as a backup in the case of malfunctioning recorders. |

Most researchers will want to have interviews transcribed verbatim from the audio recording. This allows you to refer to the exact words of participants during the analysis. Although it is possible to conduct analyses from the audio recordings themselves or from notes, it is not ideal. However, transcription can be extremely time consuming and, if not done yourself, can be costly.

In the planning phase of research, you will want to consider whether qualitative research software (eg, NVivo, ATLAS.ti, MAXQDA, Dedoose, and so on) will be used to assist with organising, managing and analysis. While these tools are helpful in the management of qualitative data, it is important to consider your research budget, the cost of the software and the learning curve associated with using a new system.

Step 5: developing the interview guide

Semistructured interviews include a short list of ‘guiding’ questions that are supplemented by follow-up and probing questions that are dependent on the interviewee’s responses. 8 17 All questions should be open ended, neutral, clear and avoid leading language. In addition, questions should use familiar language and avoid jargon.

Most interviews will start with an easy, context-setting question before moving to more difficult or in-depth questions. 17 Table 5 gives details of the types of guiding questions including ‘grand tour’ questions, 18 core questions and planned and unplanned follow-up questions.

Questions and prompts in semistructured interviewing

| Type of question | Definition | Purpose | Example |

| Grand tour | General question related to the content of the overall research question, which participant knows a lot about | ||

| Core questions | Five to 10 questions that directly relate to the information the researcher wants to know | ||

| Planned follow-up questions | Specific questions that ask for more details about particular aspects of the core questions | ||

| Unplanned follow-up questions | Questions that arise during the interview based on participant responses |

To illustrate, online supplementary appendix A presents a sample interview guide from our study of weight gain during pregnancy among young women. We start with the prompt, ‘Tell me about how your pregnancy has been so far’ to initiate conversation about their thoughts and feelings during pregnancy. The subsequent questions will elicit responses to help answer our research question about young women’s perspectives related to weight gain during pregnancy.

Supplementary data

After developing the guiding questions, it is important to pilot test the interview. Having a good sense of the guide helps you to pace the interview (and not run out of time), use a conversational tone and make necessary adjustments to the questions.

Like all qualitative research, interviewing is iterative in nature—data collection and analysis occur simultaneously, which may result in changes to the guiding questions as the study progresses. Questions that are not effective may be replaced with other questions and additional probes can be added to explore new topics that are introduced by participants in previous interviews. 10

Step 6: establishing trust and rapport

Interviews are a special form of relationship, where the interviewer and interviewee converse about important and often personal topics. The interviewer must build rapport quickly by listening attentively and respectfully to the information shared by the interviewee. 19 As the interview progresses, the interviewer must continue to demonstrate respect, encourage the interviewee to share their perspectives and acknowledge the sensitive nature of the conversation. 20

To establish rapport, it is important to be authentic and open to the interviewee’s point of view. It is possible that the participants you recruit for your study will have preconceived notions about research, which may include mistrust. As a result, it is important to describe why you are conducting the research and how their participation is meaningful. In an interview relationship, the interviewee is the expert and should be treated as such—you are relying on the interviewee to enhance your understanding and add to your research. Small behaviours that can enhance rapport include: dressing professionally but not overly formal; avoiding jargon or slang; and using a normal conversational tone. Because interviewees will be discussing their experience, having some awareness of contextual or cultural factors that may influence their perspectives may be helpful as background knowledge.

Step 7: conducting the interview

Location and set-up.

The interview should have already been scheduled at a convenient time and location for the interviewee. The location should be private, ideally with a closed door, rather than a public place. It is helpful if there is a room where you can speak privately without interruption, and where it is quiet enough to hear and audio record the interview. Within the interview space, Josselson 15 suggests an arrangement with a comfortable distance between the interviewer and interviewee with a low table in between for the recorder and any materials (consent forms, questionnaires, water, and so on).

Beginning the interview

Many interviewers start with chatting to break the ice and attempt to establish commonalities, rapport and trust. Most interviews will need to begin with a brief explanation of the research study, consent/assent procedures, rationale for talking to that particular interviewee and description of the interview format and agenda. 11 It can also be helpful if the interviewer shares a little about who they are and why they are interested in the topic. The recording equipment should have already been tested thoroughly but interviewers may want to double-check that the audio equipment is working and remind participants about the reason for recording.

Interviewer stance

During the interview, the interviewer should adopt a friendly and non-judgemental attitude. You will want to maintain a warm and conversational tone, rather than a rote, question-answer approach. It is important to recognise the potential power differential as a researcher. Conveying a sense of being in the interview together and that you as the interviewer are a person just like the interviewee can help ease any discomfort. 15

Active listening

During a face-to-face interview, there is an opportunity to observe social and non-verbal cues of the interviewee. These cues may come in the form of voice, body language, gestures and intonation, and can supplement the interviewee’s verbal response and can give clues to the interviewer about the process of the interview. 21 Listening is the key to successful interviewing. 22 Listening should be ‘attentive, empathic, nonjudgmental, listening in order to invite, and engender talk’ 15 15 (p 66). Silence, nods, smiles and utterances can also encourage further elaboration from the interviewee.

Continuing the interview

As the interview progresses, the interviewer can repeat the words used by the interviewee, use planned and unplanned follow-up questions that invite further clarification, exploration or elaboration. As DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree 10 explain: ‘Throughout the interview, the goal of the interviewer is to encourage the interviewee to share as much information as possible, unselfconsciously and in his or her own words’ (p 317). Some interviewees are more forthcoming and will offer many details of their experiences without much probing required. Others will require prompting and follow-up to elicit sufficient detail.

As a result, follow-up questions are equally important to the core questions in a semistructured interview. Prompts encourage people to continue talking and they can elicit more details needed to understand the topic. Examples of verbal probes are repeating the participant’s words, summarising the main idea or expressing interest with verbal agreement. 8 11 See table 6 for probing techniques and example probes we have used in our own interviewing.

Probing techniques for semistructured interviews (modified from Bernard 30 )

| Probing technique | Description | Example |

| Wait time | Interviewer remains silent after asking a question. This allows the interviewee to think about their response and often encourages the interviewee to speak. | (Wait, do not respond with additional questioning until participant speaks) |

| Echo | Interviewer repeats or summarises the participant’s words, encouraging them to go into more detail. | . |

| Verbal agreement | Interviewer uses affirming words to encourage the interviewee to continue speaking. | |

| Expansion | Interviewer asks participant to elaborate on a particular response. | . . |

| Explanation | Interviewer asks participant to clarify a specific comment. | |

| Leading | Interviewer asks interviewee to explain their reasoning. | . |

Step 8: memoing and reflection

After an interview, it is essential for the interviewer to begin to reflect on both the process and the content of the interview. During the actual interview, it can be difficult to take notes or begin reflecting. Even if you think you will remember a particular moment, you likely will not be able to recall each moment with sufficient detail. Therefore, interviewers should always record memos —notes about what you are learning from the data. 23 24 There are different approaches to recording memos: you can reflect on several specific ideas, or create a running list of thoughts. Memos are also useful for improving the quality of subsequent interviews.

Step 9: analysing the data

The data analysis strategy should also be developed during planning stages because analysis occurs concurrently with data collection. 25 The researcher will take notes, modify the data collection procedures and write reflective memos throughout the data collection process. This begins the process of data analysis.

The data analysis strategy used in your study will depend on your research question and qualitative design—see the study of Creswell for an overview of major qualitative approaches. 26 The general process for analysing and interpreting most interviews involves reviewing the data (in the form of transcripts, audio recordings or detailed notes), applying descriptive codes to the data and condensing and categorising codes to look for patterns. 24 27 These patterns can exist within a single interview or across multiple interviews depending on the research question and design. Qualitative computer software programs can be used to help organise and manage interview data.

Step 10: demonstrating the trustworthiness of the research

Similar to validity and reliability, qualitative research can be assessed on trustworthiness. 9 28 There are several criteria used to establish trustworthiness: credibility (whether the findings accurately and fairly represent the data), transferability (whether the findings can be applied to other settings and contexts), confirmability (whether the findings are biased by the researcher) and dependability (whether the findings are consistent and sustainable over time).

Step 11: presenting findings in a paper or report

When presenting the results of interview analysis, researchers will often report themes or narratives that describe the broad range of experiences evidenced in the data. This involves providing an in-depth description of participant perspectives and being sure to include multiple perspectives. 12 In interview research, the participant words are your data. Presenting findings in a report requires the integration of quotes into a more traditional written format.

Conclusions

Though semistructured interviews are often an effective way to collect open-ended data, there are some disadvantages as well. One common problem with interviewing is that not all interviewees make great participants. 12 29 Some individuals are hard to engage in conversation or may be reluctant to share about sensitive or personal topics. Difficulty interviewing some participants can affect experienced and novice interviewers. Some common problems include not doing a good job of probing or asking for follow-up questions, failure to actively listen, not having a well-developed interview guide with open-ended questions and asking questions in an insensitive way. Outside of pitfalls during the actual interview, other problems with semistructured interviewing may be underestimating the resources required to recruit participants, interview, transcribe and analyse the data.

Despite their limitations, semistructured interviews can be a productive way to collect open-ended data from participants. In our research, we have interviewed children and adolescents about their stress experiences and coping behaviours, young women about their thoughts and behaviours during pregnancy, practitioners about the care they provide to patients and countless other key informants about health-related topics. Because the intent is to understand participant experiences, the possible research topics are endless.

Due to the close relationships family physicians have with their patients, the unique settings in which they work, and in their advocacy, semistructured interviews are an attractive approach for family medicine researchers, even if working in a setting with limited research resources. When seeking to balance both the relational focus of interviewing and the necessary rigour of research, we recommend: prioritising listening over talking; using clear language and avoiding jargon; and deeply engaging in the interview process by actively listening, expressing empathy, demonstrating openness to the participant’s worldview and thanking the participant for helping you to understand their experience.

Further Reading

- Edwards R, & Holland J. (2013). What is qualitative interviewing?: A&C Black.

- Josselson R. Interviewing for qualitative inquiry: A relational approach. Guilford Press, 2013.

- Kvale S. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. SAGE, London, 1996.

- Pope C, & Mays N. (Eds). (2006). Qualitative research in health care.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected. Reference details have been updated.

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Mastering Semi-Structured Interviews

Introduction

What is the difference between structured and semi-structured interviews, when to use a semi-structured interview, best practices for conducting semi-structured interviews, semi-structured interviews in qualitative research.

Interviews are an integral part of qualitative and social science research . While observational research explores what people do, interviews look at what people say and believe. The interview is an important research method to capture people's perspectives and experiences concerning relevant topics.

Three different types of interviews can be utilized in research. In this article, we will look at the semi-structured interview. This form of interview offers a balance between a rigid interaction that produces neatly organized data and a fluid conversation that can explore unexpected but relevant aspects of the phenomenon under study.

Among research methods , interviewing focuses on the experiences and perspectives that people have about a particular topic. In contrast, other research methods such as experiments and observations focus on what people do or how things work. However, people may look at the same cultural or social practice and think different things about it, making interviews important to capture potential nuances in experiences and interpretations.

Conducting an interview is a more complex task than simply talking with people. Qualitative researchers can adopt three different approaches to talking with interview respondents. The most straightforward form of interview is the structured interview , which is a rigid form of interview that asks a specific set of questions. It is fully structured in that all questions are specified beforehand and the interviewer poses the same questions to all participants, without any variations or asking any follow-up questions on the spot. A strength of structured interviews is that asking only predetermined questions produces uniform data that makes comparisons across participants easier, as answers from structured interviews can be quickly sorted into a matrix or spreadsheet for simple comparison.

Another type of interview is the semi-structured interview, which also has predetermined questions but allows for follow-up questions for deeper exploration. In this case, the interview can be seen as a formal conversation, with the researcher having a predetermined set of topics and questions they want to ask, while at the same time remaining open to asking other questions as the conversation unfolds. As a result, a semi-structured interview offers the necessary flexibility for researchers to explore any relevant ideas that may emerge as the participant answers questions and shares new information.

Advantages of semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews allow the researcher to probe deeply into the perspectives of interview respondents, while structured interviews have a rigid format that does not allow for the interviewer to elicit more detail if given the opportunity.

The semi-structured format also provides the necessary guidance for researchers to stay focused on the key topics at hand. While the interview may go through the questions in a different order or explore additional topics, the predetermined questions in a semi-structured interview ensures that the important topics are sufficiently explored.

Disadvantages of semi-structured interviews

Unlike in a formal interview, the open-ended nature of semi-structured interviews can allow for the interview respondent to take the conversation in unanticipated directions. While this is a useful feature of semi-structured interviews, it is also important for the interviewer to guide the conversation toward the topic of study to ensure that the collected data will be relevant to the research question.

A semi-structured interview also requires the interviewer to engage in active listening to be able to take advantage of opportunities to ask probing questions. In this respect, interviewers may require training to ensure that they can effectively conduct a semi-structured interview that explores respondents' perspectives deeply enough while collecting data relevant to the research inquiry.

Unstructured interviews

One more distinction to keep in mind is that of the unstructured interview . While structured and semi-structured interviews have predetermined questions tailored to address the research question , unstructured interviews have no framework set before conducting the interview.

These kinds of interviews are meant to be more informal or exploratory in nature; they allow respondents to answer as freely as possible and permits the interviewer to follow the dialogue wherever it goes. While both semi-structured and unstructured interviews can employ spontaneous follow-up questions, semi-structured interviews are designed to ensure that a set of key questions are asked to all respondents to ensure relevant data is collected.

While interviews can follow predetermined structures to different degrees, interviewing as a data collection method is a social act that involves developing rapport with the interview respondent so that they feel comfortable to answer freely. This is also important to collect rich data that shed light on the phenomenon under study.

Keep in mind that any qualitative interview, regardless of type, focuses on open-ended questions. Any study that is more suited to closed-ended questions may find survey research more conducive to addressing their research inquiry.

Organize your interview data with ATLAS.ti

Powerful tools to manage and analyze research projects of all sizes. Start with a free trial today.

A semi-structured interview is ideal when you want to explore individuals' experiences and perspectives around a particular topic. It is also important to have a clearly defined research agenda with specific objectives that your interview respondents can address. Your research objectives can inform the core questions you can pose to respondents.

In addition, if you are still looking to inductively generate theory in areas that have little theoretical coherence or conceptualization, a semi-structured interview is ideal because it allows you to probe further into the ideas that emerge from your respondents. Semi-structured interviews are thus powerful data collection tools when you are looking to build a theory or explore individuals' experiences or perspectives.

Interviewing in qualitative research is not merely an act of conversing with research participants. It is a research method aimed at exploring the perspectives and ideas of research participants as deeply as possible.

When you conduct semi-structured interviews, it is important to intentionally consider every major element of the study, from the selection of participants to the questions asked, even the setting in which the interviews take place.

Preparing for a semi-structured interview

Think about which participants can adequately address the objectives in your study. For example, if your research inquiry deals with a specific cultural practice from a particular perspective, then you will benefit from choosing respondents who can best speak to that perspective.

Also reflect on how you will interact with your respondents. What is the best way to reach them and elicit their ideas? To engage in a meaningful conversation with your participants, it is important to pose questions in a way that is easy for others to understand, avoiding any jargon and preparing alternative ways to ask each question. Moreover, interview questions should be adjusted to each participant. Interviewing children is a different matter from interviewing adults. If the respondents' first language is different from yours, you may also want to consider adjusting your language to make yourself understood. The respondent's individual circumstances will play an important role in how you conduct your interview.

In addition, consider what equipment you will use to collect qualitative data in the form of audio or video recordings , and aim to record in as high a quality as possible. While the audio recorder on most smartphones is adequate enough to capture most conversations, you may want to think about using professional equipment if you are conducting interviews in public environments like cafés or parks. A camera may also be appropriate if you want to record facial expressions, gestures, and other body language for later analysis.

Semi-structured interview questions

A researcher should prepare an interview guide that lists all the necessary questions to be asked and topics to be explored. The guide can be flexible and researchers can ask the questions in whichever order naturally unfolds during the conversation. Nonetheless, having a guide helps ensure that the researcher is collecting data relevant to the research question.

When designing interview guides, consider how your questions are framed and how they might be received by the interview respondent. Avoid leading questions that may elicit socially desirable responses, and prepare alternative ways to word your questions in case participants don't understand a question.

Preparing follow-up questions

Probing questions make for effective follow-ups that encourage respondents to provide in-depth information about the topic at hand. A common challenge of interviews is that participants may provide very brief responses or not deeply engage with the conversation. Preparing prompts and probes can help researchers encourage participants to open up or provide more details if needed.

In general, an interviewer should invite the respondent to elaborate on answers when additional details can benefit the research. Taking advantage of such opportunities in a semi-structured interview can greatly contribute to the theoretical development arising from the interview study. These prompts and probes can be as simple as asking for more details, nodding along, or practicing silence. Another helpful tactic is to ask participants to provide an example or walk you through the story they are sharing.

The interview itself is just one of the components of the interview study. During and after the semi-structured interview, take the following into consideration to ensure rigorous data collection .

Collecting qualitative data in the form of interviews

In most cases, interview data takes the form of transcriptions of raw audio or video recordings of the interview conversations. It's important to ensure that you have the necessary equipment to record and transcribe the interview. Being able to count on high quality recordings is crucial to make transcription easier and more accurate.

While you can certainly analyze the actual recordings, textual data can make the analysis process easier and more manageable. You can use qualitative data analysis software such as ATLAS.ti to analyze multimedia or text data; another benefit of text data is that many additional analysis tools can be used to analyze the structure or contents of the data.

An interview researcher should also consider how the interview is conducted. After all, the two-way communication in a face-to-face interview has different effects on the interview respondent from an interview that is conducted online or by email. Be sure to familiarize yourself with the environment in which you will conduct the interview so that you can anticipate any issues that arise regarding clarity between you and your respondents.

During the course of any interview, it may benefit your analysis to capture detailed notes about the interactions you have with your respondents. A good practice is to note down any observations or impressions immediately after concluding each interview while the interaction is fresh in your mind. Many interviewers use these notes to remind them of potentially significant theoretical developments that can be used when coding the data.

Interviews with vulnerable populations

For interview projects that involve sensitive issues, the researcher should be mindful of how questions are posed and what is asked to avoid interview respondents becoming uncomfortable or anxious.

This is especially true in studies that involve children, people in conflict zones, and other vulnerable populations. The interviewer should take great care to balance data collection with the responsibility of protecting the well-being of their research participants.

Informed consent with interview respondents

In terms of addressing ethical considerations , the researcher should also ensure that they receive participants' consent before collecting any data . Informed consent is a crucial standard in research involving human participants, and it involves both the interviewer and interview respondent being cognizant of the purpose of the study, the procedures taken during the interview, and the measures in place to preserve the respondent's privacy and personal data .

Especially with respect to interviews that collect open-ended data from participants, researchers should ensure that respondents have an in-depth understanding of the interview study in which they are participating.

Preparing semi-structured interviews for analysis