PRESENTATION OF JESUS IN THE TEMPLE (Luke 2: 21)

Back to: CHRISTIAN RELIGIOUS STUDIES JSS2

Welcome to Class !!

We are eager to have you join us !!

In today’s Christian Religious Studies class, We will be discussing “Presentation of Jesus in the Temple” . We hope you enjoy the class!

Jesus Presented in the Temple

Eight days after the birth of Jesus, He was circumcised and named Jesus, as given by the angel even before He was conceived. Then it was time for the purification offering, as required by the law of Moses after the birth of a child; so his parents took him to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord. The law of the Lord says, “If a woman’s first child is a boy, he must be dedicated to the Lord.” So they offered a sacrifice according to what was required in the law of the Lord “either a pair of turtle doves or two young pigeons.”

The Importance of a Child’s Presentation in the Church

The Jewish practice of presenting the firstborn to the Lord has been adopted by the church. But in our churches today, we do not only present the firstborn but all our children. Presentation of our children is for the purpose of christening the child and giving him/her a Christian name.

Two people of God made prophecies during the presentation of Jesus.

The Prophecy of Simeon (Luke 2:25-35)

Simeon was a righteous and devout man. He lived in Jerusalem and had been promised by the Holy Spirit that he would see Jesus before his death. So he was in the temple when he was brought for presentation, he took Jesus in his arms and blessed God.

The Significance of the Prophecy of Simeon

- The first part of Simeon’s prophecy refers to God’s plan to save mankind. With the birth of Jesus Christ, God fulfilled His plan to save the world.

- The second part of Simeon’s prophecy refers to the response of the Israelites to the ministry of Jesus that as many people that accepted Jesus would be saved and those who reject Him would not be saved.

- The sign of a sword piercing through Marys soul refers to the anxious moments that Mary would experience as Jesus carried out His ministry. And Mary had such moments during the arrest, trial and death of Jesus.

The Prophecy of Anna (Luke 2:36-40)

Anna was an old woman of 84 years, a prophetess and the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher. She was a widow and lived with her husband for seven years before his death. All her time in the temple, worshipping God with prayers and fasting day and night.

She was in the temple during the presentation of Jesus, she gave thanks to God and spoke of Jesus Christ to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem.

The Significance of the Prophecy of Anna

Anna’s prophecy confirmed the fact that the time to save the world had come, with the birth of Jesus.

Moral Lessons

- We must learn to pray to God through Jesus Christ to help us cooperate with all those who are older than us in training us to be obedient, respectful and hardworking so that we can grow up to become upright and responsible Christian citizens.

- We must learn to see ourselves as children of God walking in the light of Christ and avoid all the deeds of darkness.

Share this lesson with your friend!

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

8 thoughts on “PRESENTATION OF JESUS IN THE TEMPLE (Luke 2: 21)”

The lesson is valuable. I really appreciate your hard work.

Thank goodness.other did not give me this

Thanks God bless you richly

it gave me what I needed others didn’t give me this

This is a wonderful story I love how it was.

God bless you richly for your good deeds

We’re glad you found it helpful😊 For even more class notes, engaging videos, and homework assistance, just download our Mobile App at https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.afrilearn . It’s packed with resources to help you succeed🌟

so happy I can write my lesson with this thanks

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

ClassNotes.ng is an Afrilearn brand.

- 08051544949

- [email protected]

- Teach for CN

- Testimonials

- Terms of use

- Privacy Policy

Weekly Newsletter

By registering, you agree to our Terms & Conditions .

- +2348180191933

- Login or Register

- $ US DOLLAR

- How It Works

Christian Religious Studies (CRS) JSS2 First Term The presentation of Jesus in the Temple

- The presentation of Jesus in the Temple

Christian Religious Studies J.S.S2 First Term

Sub-theme: Baptism and Temptation of Jesus

Performance objectives

Students should be able to:

1. Give another name of the presentation in our present time in the church.

2. Narrate the story of Jesus presentation in the temple.

Jesus presentation in the Temple (Luke 2:21-40)

Presentation in today’s time in churches is known as dedication and thanksgiving and it has been practised even before the birth of Jesus Christ

Subscribe now to gain full access to this lesson note

Click here to gain access to the full notes.

- The Birth of Jesus I

- The Birth of Jesus II

- The Birth of Jesus III

- Jesus and his Family

- The Baptism and Temptation of Jesus I

- The Baptism and Temptation of Jesus II and III

- Some temptations in Nigeria today and ways of overcoming them

- The prophecy of Simeon and the prophecy of Anna

- Chapters 12

- Category JSS2

- Author ClassNotes Edu

For Schools & Teachers

For Schools and Teacher who want to subscribe to all of the subjects, a class or term at a discounted price.

Create Your Bundle

Need many subjects? Waste no time. Select many subjects together in one subscription at a discounted price.

scholarship. serving. ministry.

The presentation of Jesus in the temple in Luke 2

The lectionary reading for Epiphany 4 in Year C is Luke 2.22–40 as we celebrate the Presentation of Jesus in the temple in Jerusalem; this is also celebrated as the feast of Candlemas(s) and in many churches it marks the formal end of the Christmas season. (In the Church of England lectionary, we have this reading both for Epiphany 4 and the Presentation, though other versions of the RCL continue reading in Luke 4 for Epiphany 4. In Years A and B, the readings for Epiphany 4 are from Matthew 5 and Mark 1.)

If you are following Luke in the lectionary, this will all feel slightly odd; last week we heard about the beginning of Jesus’ teaching ministry in the synagogue in Nazareth, and have already reflected on the ministry of John the Baptist and Jesus’ own baptism, as well as the miracle in Cana . So this is a step back in the narrative before we move on to the catch of fish in Luke 5 and then loop back again to the temptations of Jesus at the beginning of Lent. It feels a bit like playing gospel narrative hop-scotch!

James Blandford-Baker and I discuss the passage in the video here; below it you can find the usual article discussing the text in detail underneath it.

This section in Luke 2 continues Luke’s unique nativity material; Matthew moves straight from the events surround the birth, including the visit of the Magi and the flight to Egypt, to the ministry of John the Baptist. But, in keeping with first-century expectations of a ‘life’ of a significant person, Luke offers (brief) descriptions of Jesus’ upbringing, including the episode in the temple when he is 12 years old.

The narrative once more includes three characteristic emphases of Luke’s work: the importance of Jewish pious devotion as the context for all that happens; the active role of the Spirit in directing events; and the understanding of Jesus as the fulfilment of eschatological hopes.

1. Jewish pious devotion

The whole narrative section begins and ends with an emphasis on pious devotion in fulfilment of the requirements of the law; the ‘requirement of the law of Moses’ in Luke 2.20 is matched by ‘required by the law of the Lord’ in Luke 2.39. We have already been told that Jesus was circumcised (and named) on the eighth day in the previous verse, and now Luke describes two important acts that follow on, the purification of Mary and the dedication of the child, interleaved as chiasm:

A ‘purification rites’ B ‘present him to the Lord’ B’ ‘as it is written… “every male is to be consecrated..”‘ A’ ‘to offer the sacrifice…’

The regulation cited in the outer theme A–A’ is set out in Lev 12.1–8; a woman who has given birth is ceremonially unclean (which, note, has nothing to do with sin) for different lengths of time (depending on whether the child born is a boy or a girl) in this case, for 33 days, so we are a month on from the date of circumcision. It is often noted in preaching that Mary and Joseph offer the more affordable of the two possible sacrifices as a concession to poverty—but in fact Luke makes nothing of this, and the emphasis is not on this, but on their compliance with the requirements set out in the Law. And we need to beware of projecting our own socio-economic framework on a different culture, where even skilled craftsmen might still be not far from subsistence living. Like other aspects of the birth narrative, this doesn’t really suggest that they were particularly poor ; it just identifies them as ordinary .

The inner theme of Jesus’ presentation comes from the offering and redemption of the first-born sons (and animals) set out in the Exodus narratives. This offering and redemption appears to have two explanations. The first is in connection with the Passover deliverance itself; in Exodus 13.1–16, the firstborn are to be dedicated to and redeemed from the Lord in parallel with the loss of the firstborn of the Egyptians when the angel of death passes over.

This offering of the firstborn is reiterated in Num 18.14–16, though now in the context of the priestly role of the the tribe of Levi. This goes back to the incident of the Golden Calf in Ex 32; whilst those in the other tribes committed idolatry by bowing down to the calf, the tribe of Levi alone kept themselves pure, so that we read in Num 3.11–12 that the tribe of Levi now has this priestly task .

Originally, God intended that the first-born of each Jewish family would be a kohen – i.e. that family’s representative to the Holy Temple. (Exodus 13:1-2, Exodus 24:5 Rashi) But then came the incident of the Golden Calf. When Moses came down from Mount Sinai and smashed the tablets, he issued everyone an ultimatum: “Make your choice – either God or the idol.” Only the tribe of Levi came to the side of God. At that point, God decreed that each family’s first-born would forfeit their “kohen” status – and henceforth all the kohanim would come from the tribe of Levi. (Numbers 3:11-12)

What is striking in Luke’s narrative is that, though Jesus is dedicated to the Lord in the temple, he is not redeemed and thus exempted from priestly service. Like Hannah’s dedication of Samuel in 1 Samuel 1.24–28, Jesus remains dedicated to the Lord, which makes the episode in the temple when Jesus is 12 seem to follow on quite naturally. It also signals that Jesus’ ministry will restore to God’s people their priestly role, an idea that is picked up in Revelation as one of its points of connecting with Luke’s gospel. In Rev 1.5–6, Jesus is the one who has ‘freed us from our sins’ and ‘made us to be a kingdom and priests’ to serve God, taking up the pre-Golden-Calf language of Ex 19.6. In Rev 7.3, God’s people are sealed on their foreheads with the seal of the living God, which turns out in Rev 14.1 to be the name of the lamb and God, and by Rev 22.4 this turns out to be the high-priestly adornment as they do priestly service in the presence of God in the New Jerusalem which is shaped as a cube like a giant Holy of Holies.

The integration of these two rites serves to emphasise Mary and Joseph as pious observant Jews, which has two effects. First, it undoes the common claim that Jesus welcomed the outsider, but rebuked the religious; throughout Luke it is both the religiously observant and the ‘sinner’ who hears the good news. Second, it contributes to a consistent assertion that God honours the devotion of his people, a theme continued in Acts as the early followers of Jesus continue to worship in the temple.

2. The role of the Holy Spirit

The emphasis on pious devotion is interweaved in this passage with the importance of the role of the Spirit, just as it has already been in the case of Mary (humbly devoted and then clothed with the Spirit and power) and will be in Jesus’ temptations (disciplined obedience which leads to being filled with the power of the Spirit).

Simeon is ‘righteous and devout’ ( dikaios kai eulabes ); the term for ‘devout’ here only occurs in Luke’s writings (Acts 2.5, 8.2 and 22.12) but its cognates also occur in Heb 5.7, 11.7 and 12.28 to describe Jesus, Noah and the gathered followers of Jesus in worship. Although the ‘righteous’ are contrasted with the ‘sinners’ Jesus has come to call to repentance, it is clear in Luke (and especially in Matthew) that being ‘righteous’ is a positive quality to be desired and pursued. But along with this, there is a threefold emphasis on the Spirit: the Spirit is ‘upon him’; the Spirit has ‘revealed to him’ that he will see the Messiah; and the Spirit ‘moves him’ to go to the temple at that moment. It is safe to assume that the Spirit has also moved him, like Mary and Zechariah before him, to utter a prophetic oracle often now known by its opening line in Latin translation, the Nunc Dimittis (‘Now you dismiss…’). Given the juxtaposition of pious devotion and the Spirit, it seems fitting that Simeon’s prophetic utterances now finds its place in Anglican pious devotion as part of Night Prayer in Common Worship (previously in Evening Prayer in the BCP).

The description of the prophetess Anna provides a parallel with the description of Simeon, as one of Luke’s many male-female pairs. Her pious devotion is expressed in narrative terms, as she prays and fasts in the temple in her widowhood. The detail on fasting reflects a special interest of Luke; he offers us detail that the other gospels omit, namely that Jewish devotion involved ‘frequent’ fasting (Luke 5.33), and that this took place on two days a week (Luke 18.12) which we know from the Didache happened to be Mondays and Thursdays. Luke makes much of meals and eating, as symbolising messianic rejoicing; as its converse, fasting symbolises both sorry for sin and exile, and a longing for the messiah to come. Thus here is is connected with Anna’s anticipation of the ‘redemption of Jerusalem’ (the city serving as a metonym for the whole nation). Luke doesn’t mention the Spirit explicitly in relation to Anna, but like Simeon she offers a prophetic comment on the child.

We might say that, for Luke, the disciplines of pious devotion form the vessel into which he pours his Spirit, and without the Spirit such a vessel is empty. On the other hand, the work of the Spirit issues in these devotions of discipline, and without such disciplines the work of the Spirit is incomplete.

3. The fulfilment of God’s promise

The statements of both Simeon (recorded in detail) and Anna (offered in summary) are saturated with the theme of the eschatological fulfilment of the promise of God, as have (in their different ways) the first two of the three canticles in this part of the gospel. This theme will be repeated again in both the ministry of John the Baptist and the teaching of Jesus in Nazareth. There are some important things worth noting about the nature of this fulfilment.

First, Simeon follows Mary in seeing God’s promises already fulfilled in the person of Jesus. Where Zachariah, in the Benedictus, retains a future sense, Simeon (with the Magnificat) uses the language of realised salvation. Even though all that was promised has not yet happened, the confidence in the person of Jesus is such that it is as if we already have all the answers to the hopes that we longed for.

Second, this fulfilment is rooted in Scripture . Every line of the Nunc Dimittis echoes one of the promises in Isaiah 40–66.

And the glory of the LORD will be revealed, and all people will see it together. (Is 40.5) I will keep you and will make you to be a covenant for the people and a light for the Gentiles. (Is 42.6) Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the LORD rises upon you. (Is 60.1)

(See also Is 46.13, 49.6, 52.10 and 56.1).

Thirdly, this biblical pattern of promise is also personally fulfilled . Just as God has promised something to his people, which he now fulfils in Jesus, so God has promised something to Simeon (that he will not die…) which he now fulfils in Simeon’s encounter with Jesus (…until he has seen with his own eyes). The Spirit of God in Simeon has brought the word of God to Simeon, just as the Spirit has brought the word of God to his people in scripture.

Fourth, all these announcements are marked by joy and wonder , as have all the events around Jesus’ birth, both for those bringing the word of disclosure and for those who hear those words. The theme of joy continues to be a significant part of Luke’s account, both in the gospel and in Acts.

Fifth, and in some contrast, they also include warnings of division and pain . This will affect both the nation (‘the rising and falling of many’, Luke 2.34) and the individuals involved, especially Mary herself. The ‘sword that pierces her heart’ (Luke 2.35) might refer to the demotion of Mary in importance for Jesus as she takes second place to the imperative of gospel ministry, but it surely reaches its clearest fulfilment in her witnessing her son’s excruciating death on the cross.

Joel Green, in his NIC commentary on Luke, notes the wide number of themes in this short passage which interconnect with themes already present from the beginning of the third gospel.

There is much to learn from the individuals in the narrative, but if we are going to focus on the most important thing in preaching (not what we must do but what God has already done) we might note in this passage that God honours pious devotion, God sends his Spirit to guide, reveal and speak, and God fulfils all his promises in the person of Jesus.

(The artwork at the top is The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple by Philippe de Champaigne , 1648.)

We will look at: t he background to this language in Jewish thinking; Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 24 and Mark 13; t he Rapture—what is it, and does the Bible really teach it; w hat the New Testament says about ‘tribulation’; t he beast, the antichrist, and the Millennium in Rev 20; t he significance of the state of Israel.

The cost is £10 per person, and you can book your tickets at the Eventbrite link here .

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo . Like my page on Facebook .

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis . If you have valued this post, you can make a single or repeat donation through PayPal: For other ways to support this ministry, visit my Support page .

Comments policy: Do engage with the subject. Please don't turn this into a private discussion board. Do challenge others in the debate; please don't attack them personally. I no longer allow anonymous comments; if there are very good reasons, you may publish under a pseudonym; otherwise please include your full name, both first and surnames .

Related Posts:

10 thoughts on “The presentation of Jesus in the temple in Luke 2”

Ian, One of the striking aspects concerning Jesus to be found in these early chapters of Luke is the stress on his authority and power : “He will baptise you with the Holy Spirit and with fire” [1:16] ; “Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit —and was led by the Spirit in desert”[4:1]; and “Jesus returned to Galilee in the power of the Spirit —–and he taught in their synagogues, and everyone praised him.” [4:14]. And yet – in Nazareth? They too recognized this authority and power, but if we allow Mark to contribute to this scene, it compliments what Luke is declaiming: “He could not do any miracles there — — he was amazed at their lack if faith” (ESV -“unbelief”) [Mark 6: 5-6]. Jesus did not acquiesce in this atmosphere of outright hostility and venom. He did not try to placate his detractors. On the contrary he went on the offensive (not, I hasten to add, by his attitude and demeanour, but by employing the Tanach to devastating effect)! There are (at least ) two conclusions to be drawn from this:- First, This passage illuminates the forcefulness, the singlemindedness and the refusal to compromise the truth of the Word of God; something that is clearly exhibited, not only in Christ’s preaching/teaching , but in his whole being. Secondly, this encounter begins a train of events (and continued in The Acts) which reveal that being empowered by the Holy Spirit does not neseassarily lead to unalloyed bliss. On the contrary, it led to persecution and death. And it is no different for this generation!

Yes, I would agree with you. I note quite often in the texts on Luke that he specifically makes reference to power, sometimes where the other gospels omit it.

I think this continues through Acts—the apostles exercise a spiritual power which is at odds with the institutional power of the Jewish leaders.

Than you Ian. You put a lot of work into these posts.

Does Jesus not being ‘redeemed’ also point to his sinlessness; there was no need for him to be redeemed?

You speak of Jesus’ priestly role. I agree. Christ acted as a priest but was not formally a priest. Sometimes we lose sight of the book of Hebrews – if Jesus were on earth he would not be a priest. He came from the wrong tribe. And so his priesthood comes through Melchizedek. It functions from heaven as part of his enthronement and his indestructible life.

Your point that all God’s people are now priests is intriguing. We are all kings too. I’m wondering if the Bible comments on the democratising dynamic. Christ has made us a kingdom of priests. Is this the work of the indwelling Spirit that equips us for a priestly role?

Ian Paul – that was a very nice post – many thanks for putting it up and all the work you put into it.

One issue that arises is pious devotion. Some of the things you mention were clearly prescribed in the Pentateuch; they are meticulously following these things, but they belong to the ceremonial law which was fulfilled and no longer plays any role (circumcision, the length of time one is ceremonially unclean after birth, what one is supposed to do at the end of this period, etc …).

Other things don’t seem to fall into this category. Is there any mention in the Pentateuch of fasting, specifically on Mondays and Thursdays?

So I’m wondering – what would constitute `pious devotion’ which is pleasing to God for Christians living in the 21st century? Clearly the Pharisees thought that their rigorous lifestyle corresponded to `pious devotion’, but Jesus only has condemnation for them. So – what should we be doing?

” – the apostles exercise a spiritual power which is at odds with the institutional power of the Jewish leaders”. Absolutely true! However let’s bring this up to date. “In the last days —- there will be times of difficulty ——–“. There will be those who have “the appearance of godliness but denying its power”. Without entering into a debate on the meaning of the last days, we are now witnessing a Westernised Christianity (not least within Anglicanism) which possesses a form of institutional *authority” – but with a growing declivity in *spiritual power* ; a manifestation I would suggest of a desire, among other things, to recreate a Jesus Christ who somehow conforms to the ever present need in some quarters for *relevancy* (conformity?) to secular values; a Jesus, perhaps, who in response to the question ” Is this not Joseph’s son ?” would probably have answered: ” That doesn’t matter really. I’m only here for you”.

Colin – perhaps true where you are. Right now, I’m living in a Catholic country, where the regime panders to the ultra-religious head bangers. They’re certainly not trying to recreate a Jesus Christ who conforms to secular values – quite the opposite.

How does one comment regarding a situation where information regarding the country is non-existent and where the ecclestical information is sparse – except to say that I have a long- standing, working knowledge of a European country with a Catholic majority. As far as I am concerned, what you have presented Jock is the exception; not the rule!

Colin – yes – I think you hit the nail on the head there.

Apologies for giving “ecclesiastical” short shrift!

Colin – absolutely no problem – you’re right about it being the exception. I’d simply prefer not to go any further down that road and give details, since Ian Paul put up a very nice post – and I don’t want to be responsible for taking the comments section `off topic’.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest Grove Booklet

Ian Paul: theologian, author, speaker, academic consultant. Adjunct Professor, Fuller Theological Seminary ; Associate Minister, St Nic's, Nottingham ; Managing Editor, Grove Books ; member of General Synod. Mac user; chocoholic. Tweets at @psephizo

More About Ian...

To make a one-off or repeat donation to support the blog, use PayPal with the button below:

You can also visit my Patreon page .

For other ways to support this ministry, visit my Support page .

Email Updates

Recent posts.

My Recent Publications

Other Publications

Andrew Goddard Bible biblical interpretation Biblical literacy biblical theology Christmas Church of England culture discipleship discussion doctrine eschatology evangelism gay General Synod Grove guest Hermeneutics History hope interpretation James Blandford Baker Jesus John's gospel Justin Welby leadership lectionary Luke Luke's gospel Mark's gospel Matthew ministry mission New Testament Old Testament Paul politics preaching Revelation same sex unions sexuality theology video Year B Year C

- Job Recruitment

- Church Talk

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

What Is the Significance of The Presentation of Jesus in The Temple

The presentation of Jesus in the temple is significant because it marks the beginning of Jesus’ life as a man, and demonstrates his holiness.

Jesus was born to fulfill a prophecy in the Old Testament that said that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem, which is why Mary and Joseph traveled there after they heard about it. However, according to Jewish law, all males were required to be circumcised when they turned eight days old. Since Jesus wasn’t yet eight days old when he was born, Mary and Joseph went back to Jerusalem for him to be circumcised—and for him to be presented in the temple.

The presentation of Jesus in the temple is important because it shows his parents’ devotion to God: they followed the law closely even though it was inconvenient for them. Also, since this was an important event in their son’s life, we can assume that they would have been open about who he was and what he meant for them.

Importance of Jesus’ Parents’ Devotion to God

Openness about jesus’ identity.

Presentation of Jesus in the Temple

The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple celebrates an early episode in the life of Jesus. It falls between the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul on January 25 th , and the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter on February 22 nd . In the Roman Catholic Church, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple is the fourth Joyful Mystery of the Rosary.

The event is described in the Gospel of Luke, 2:22-40. According to the gospel, Mary and Joseph took the baby Jesus to the Temple in Jerusalem forty days after his birth to complete Mary’s ritual purification after childbirth, and to perform the redemption of the firstborn, in obedience to the Law of Moses, Leviticus 12, Exodus 13:12-15. Luke explicitly says that Joseph and Mary take the option provided for poor people, those who could not afford a lamb, sacrificing a “pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons”. Leviticus 12:1-4 indicates that this event should take place forty days after the birth of a male child, and that is whey the Church celebrates the Presentation in the Temple forty days after Christmas.

As they brought Jesus into the temple, they encountered Simeon. The Gospel records that Simeon had been promised that “He should not see death before he had seen the Lord” Luke 2:26. Simeon prayed the prayer that would become known as the “Canticle of Simeon”, which prophesied the redemption of the world by Jesus: “Lord, now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace; according to Thy word; for mine eyes have seen Thy salvation, which Thou hast prepared before the face of all people; to be a light to lighten the gentiles and to be the glory of Thy people Israel”, Luke 2:29-32. Simeon then prophesied to Mary, “Behold, this child is set for the falling and the rising of many in Israel, and for a sign which is spoken against. Yes, a sword will pierce through your own soul, that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed”, Luke 2:34-35. The Elderly Prophetess Anna, was also in the Temple, and offered prayers and praise to God for Jesus, and spoke to everyone there about Jesus and his role in the redemption of Israel, Luke 2:36-38.

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple and the Testimonies of Simeon and Anna: Luke 2:21-38

Extracted from The Testimony of Luke, by S. Kent Brown

Luke 2:21–24, New Rendition

21 And when eight days for his circumcision were fulfilled, then his name was called Jesus; it was so named by the angel before he was conceived in the womb. 22 And when the days for their purification were fulfilled, according to the law of Moses, they brought him up into Jerusalem to present him before the Lord, 23 just as it was written in the law of the Lord that, “Every male who opens a mother’s womb shall be called holy to the Lord,” 24 and to offer a sacrifice according to what was spoken in the law of the Lord, “Either a pair of turtledoves or two young doves.”

2:21 eight days . . . for the circumcising . . . his name was called: As is apparent here and in 1:59, both circumcising and naming a male child occur on the eighth day. Among ancient sources, only Luke preserves this linkage.

conceived in the womb: The force of this expression is to say that Jesus comes to birth as other children do: in a natural manner. He is fully and physically a part of this world and is not a metaphysical, mythological creature.

2:22 purification: A woman is to pay a five-shekel tax and offer sacrifice for ritual purity after giving birth to her firstborn—forty days after a male child and eighty after a female (see the Note on 2:23). Until she does so, she is judged to be ritually unclean. The sacrifice is to consist of a lamb and either a young pigeon or a turtledove. For the poor, the sacrifice is to be either two pigeons or two turtledoves, the offering that Luke affirms in 2:24 (see Ex. 13:2, 11–13; Lev. 12:2–8). Importantly, the best manuscripts read “their purification” rather than “her purification.” The discussion is whether the pronoun “their” points to Mary and Joseph or to Mary and Jesus as needing purification. In light of the plural “their,” if Luke obtains his information from Mary about her experience, then he misunderstands it.

according to the law: The concern with the law here and in later verses has to do with the respect for law and custom that Joseph and Mary exhibit. It also has to do with reverencing the Mosaic law in particular, giving this legal code its due respect as law from God (see the introduction to chapter 1, section C, and the Analysis on 2:21–24 below).

they brought him: This action of bringing the infant Jesus to the temple recalls Hannah’s act of bringing her son Samuel to the sanctuary (see 1 Sam. 1:24). This sort of action is implied in Jesus’ later journey to the temple with his parents (see 2:42), thus forming connections between this account and Hannah’s story.

to Jerusalem: More properly, “up to Jerusalem,” preserving the notion of the sacred, elevated geography of the city.

to present him: As the next verse implies, the intent is to offer the five shekels that redeem the firstborn (see Ex. 13:2, 11–15; 34:19–20; Num. 18:15–17), as is hinted at in 2:27. To be sure, Jesus is already dedicated to God by the words of the angel (see 1:31–33), perhaps mirroring the pattern of Hannah (see 1 Sam. 1:11).

2:23 Every male that openeth the womb: Even though Luke mentions the need to redeem the child here, the offering noted in 2:24 is not the redemption offering of five shekels. Instead, it is the purification offering made by poor people for a new mother (see the Note on 2:22). The verb “to open” (Greek dianoigō ) appears in the Septuagint tied not only to the first, sacred manifestation of life from a female, whether a woman or an animal, underlining its link to holiness (see LXX Ex. 13:2, 12–13, 15; 34:19; etc.), but also to the opening of celestial understanding (see LXX Gen. 3:6, 8; also LXX Hosea 2:15). It is in this latter sense that the verb appears later in Luke’s narrative, highlighting the Risen Jesus as the one who opens the understanding and holds the keys to opening the scriptures (see the Notes on 24:31, 32, 45). Moreover, because this verb occurs only here and at the end of Luke’s account, it forms an inclusio that emphatically underscores the unity of the whole Gospel.

holy to the Lord: Although it is true that the firstborn child belongs to God and thus parents must redeem the child by offering sacrifice, as underlined in the Exodus story (see Ex. 13:2), also implicit in this passage stands Jesus’ holiness, as well as the holiness of children in general, which is respected and preserved when the angel of death passes over the homes of the Hebrew slaves (see Ex. 11:4–5; 12:12–13, 23, 27).

2:24 A pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons: For these purification offerings, see Leviticus 12:6–8. In accord with this law, Mary offers a gift of the poor, costing an eighth of a denarius per bird (see the Note on 7:41). She holds her infant son while watching the sacrificial process from the Court of the Women where she can see clearly the altar of sacrifice and the sanctuary through the large Nicanor Gate that leads from the Court of the Women into the inner courts of the temple. As an adult, Jesus will return to this same Court of the Women and witness another poor woman, a widow, offer a gift of “all the living that she had” (21:4; see the Notes on 21:1–2 and the Analysis on 21:1–4).

At the heart of these verses beats the principle of respect for law. In a concrete sense, Mary and Joseph fit snugly within this picture. It seems that Luke’s report takes pains to note that those associated with the momentous events that lead to the Christian movement are, as we might expect, upright and honorable people before the law. Unlike others who revolt when the census is declared (see Acts 5:37), Mary and Joseph comply with the new law. Unlike those who seek to kill Jesus (see 22:2; Matt. 2:20), they do not break any of the Ten Commandments. Unlike those who stand as protectors of the law of Moses but break its tenets (see 9:22; 19:47; 20:46–47; 22:2), they obey the law, even its minor points.

A good reason stands behind this portrait. Luke seeks to answer questions about Christianity that have arisen in the larger Roman world, a world that his friend Theophilus represents (see 1:3; JST 3:19; Acts 1:1). After all, within recent memory there has been a bitter war between Jews of Palestine and Roman legions which ends with the fall of Jerusalem and its temple in Ad 70, as well as Masada a few years later. Romans have long identified Christians simply as Jews. But Luke seeks to set the record straight by clarifying that Christians, and those involved in founding their movement, are very different from other Jews (see 1:6; 2:4–5, 22, 24, 27, 39, 42, 51; etc.; the introduction to chapter 1, section C). Significantly for him in his continuing story, it is Jews who inflame the unruly crowds that oppose Paul and his companions in Asia Minor and elsewhere (see Acts 13:50; 14:2, 19; 17:5, 13; etc.).

In another vein, amidst these verses we meet other possible connections to Hannah, mother of the prophet Samuel (see the introduction to chapter 1, section D; the Notes on 1:46–48; the Analysis on 1:5–25). They have to do with the presentation of a child. Only in the story of Hannah do we see a mother bringing her firstborn son to the temple to present him to the Lord. Only in the story of Hannah do we read of a woman offering sacrifice for her new son. Only in the story of Hannah do we witness a parent redeeming a son (see 1 Sam. 1:24–28). Though the law requires these acts of parents, it is only in the stories of Hannah and Mary that we see such actions carried out. The possible echoes are not to be missed.

One further observation needs attention. Jesus comes to the temple very early in his life in the arms of his mother, who is a poor young woman, as her redemption offering of two birds illustrates (see 2:24). The place where Mary brings him is the Court of the Women where she can see both the sacrificial altar and beautiful sanctuary through the connecting Nicanor Gate. Notably, in one brushstroke, Luke’s Gospel paints Jesus’ life with the color of poverty in a place where the opulence of the temple is stunningly visible. As an adult, literally at the end of his life, with only a couple of days until his arrest, Jesus sits in the same courtyard and sees poverty, this time also in the person of a poor woman, a “poor widow” who “of her penury hath cast in all the living that she had” (21:2, 4). In a literary sense, Luke encloses his report of Jesus’ life within the notices of poor women in the temple’s Court of the Women whose circumstances in life contrast sharply with the visible luxuriousness of the temple. He knows poverty, both spiritual and physical; he comes to help those who seek a way out of their spiritual and economic penury.

Simeon (Luke 2:25–35)

New Rendition

25 And behold, there was a man in Jerusalem named Simeon, and this man was righteous and devout, waiting for the encouragement of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was upon him. 26 And revelation had been given to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not see death before he should see the Messiah of the Lord.

27 And he came in the spirit to the temple precinct when the parents were taking the child Jesus in so that they could do for him according to the custom of the law. 28 And he took him into his arms and blessed God and said,

29 “Now you are releasing your servant, Master,

according to your saying, ‘in peace,’

30 because my eyes have seen your salvation

31 which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples,

32 a light for enlightening nations

and the glory of your people Israel.”

33 And his father and mother marveled at the proclamations concerning him. 34 And Simeon blessed them and said to Mary his mother, “See, this boy is positioned for the falling and rising up of many in Israel and for a sign to be spoken against 35 (but a sword shall run through your own soul, too) so that the designs of many hearts shall be revealed.”

2:25 just: The term, which is made emphatic by the addition of the word “devout,” is better rendered “righteous,” as in 1:6, where it is applied to Zacharias and Elisabeth (Greek dikaios ; see the Notes on 1:6 and 23:50).

waiting: Luke writes this same verb (Greek prosdechomai ) to characterize Joseph of Arimathea, placing them on the same turf. By doing so, he creates a literary inclusio that arcs across his record from beginning to end, tying it together (see the Note on 23:51).

consolation: The noun (Greek paraklēsis ) is related to the term that is translated “comforter” elsewhere (see John 14:16, 26).

the Holy Ghost was upon him: This notation first explains how Simeon is able to find Joseph and Mary in the huge complex of the temple grounds (see the Note on 2:27) and, second, identifies one important result of a righteous life. In addition, Luke’s introduction to Simeon seems to suggest that he is not noisy about this spiritual gift that comes to him but is instead quiet and circumspect, his righteousness and devotion clearly visible to God.

2:26 it was revealed unto him by the Holy Ghost: Luke’s report about the righteous Simeon holds up the eternal principles that revelation can be personal and that it always comes through the Holy Ghost. In Simeon’s case, we do not know whether the revelation comes to him before the angel Gabriel appears to Zacharias and then Mary, or afterward.

the Lord’s Christ: The expression preserves the archaic sense of the term Christ, or Messiah: “the Lord’s anointed one.”

2:27 came by the Spirit into the temple: A miracle is at work. The temple complex, indicated by the Greek term hieron, is distinct from the sanctuary (Greek naos ) and is large and generally crowded (see the Note on 1:9). That the Spirit leads Simeon to Joseph and Mary, with their child, is miraculous.

to do for him after the custom of the law: The expression hints at the five shekel payment to be made for the firstborn (see the Notes on 2:22–23).

2:29 now lettest thou thy servant depart: The Greek verb “depart” stands here as a euphemism for “to die,” though it is not the usual term for dying (Greek apoluō ). Customarily, it means “to send [someone] away,” or “to release [a prisoner]” as in 8:38 (“Jesus sent him away”) and 23:25 (“[Pilate] released unto them [Barabbas]”). The tense is a simple present indicative, “Now you are letting your servant depart,” though it may well carry a modal sense that expresses a strong wish, because it stands in a hymn of praise. It may also bear a future meaning, “Now thou wilt dismiss thy servant.” The juxtaposition of the terms “servant,” which Mary applies to herself (see 1:38), and “Lord” point to the act of manumission, freeing a slave. This hymn, as recited by Simeon in 2:29–32, is titled Nunc Dimittis from the opening words of the Latin version.

2:30 thy salvation: In Hebrew or Aramaic, which Simeon is doubtless speaking, the term “salvation” comes from the same root that the name Jesus does (Hebrew yāša‘, “to deliver”), thus forming a play on words.

2:31 all people: Simeon strikes a chord that will come to characterize Jesus’ (and Luke’s) interest in the gospel spreading to everyone (see the Notes on 6:17; 8:26; 10:1, 7, 33; 11:29; 13:29; 17:16; 19:46; 24:47), a point that receives confirmation in the reference to Gentiles in 2:32.

2:32 A light to lighten the Gentiles: The expression recalls the Septuagint readings for Isaiah 42:6 and 49:6, “a light of the Gentiles.” These passages tie to the four prophetic “Servant Songs” that anticipate the coming of the Servant-King (see Isa. 42:1–4; 49:1–6; 50:4–9; 52:13–53:12). Simeon’s words can be rendered “a light for revelation to the Gentiles.” One finds a similar expression applied to the Apostle Paul in Acts 13:47.

the glory of thy people Israel: In another allusion to Isaiah’s language (see Isa. 46:13, “I will place salvation in Zion for Israel my glory”), Simeon draws attention to the two peoples whom Jesus’ message will touch, Gentiles and Jews.

2:33 Joseph and his mother: The oldest manuscripts read, “his father and mother,” no doubt underlining Joseph as the legal father, rather than biological father, who raises Jesus. Later texts add the name Joseph to remove any ambiguity that Joseph is not the father, a feature of verse 43.

2:34 Simeon blessed them: There seems to be an omission in Luke’s account, for he preserves only Simeon’s blessing of Mary in the next verse, not his blessing of Joseph, or even a combined blessing.

fall and rising again: The image of falling appears also in 20:18. Both passages take up a theme found in Isaiah 8:14–15 where “a stone of stumbling and . . . a rock of offense” cause people to “stumble, and fall, and be broken.” The word translated “rising again” refers elsewhere in the New Testament to the resurrection (Greek anastasis ). We compare the notions of rising, or ascending, and falling in the earliest mention of the Messiah as “the Rock”: “whoso . . . climbeth up by me shall never fall” (Moses 7:53).

a sign which shall be spoken against: Simeon prophesies that Jesus, who is the sign itself, will face pugnacious opposition, indicated by the Greek participle antilegomenon, which here bears the sense of “contested.” But that opposition will “be revealed” to others (2:35), an important prophecy about Jesus’ role in exposing this sort of evil (see 6:6–11; John 15:22).

2:35 a sword shall pierce through thy own soul: These words, spoken almost as an aside, disclose to Mary that the future of her son will bring pain of soul to her. We imagine that, on occasion, she is a witness to ill treatment of her son by opponents, perhaps by persons whom she knows. We know for certain that she witnesses his death on the cross, an event that brings anguish upon her (see John 19:25–27; compare Matt. 27:55–56; Mark 15:40–41; Luke 23:49).

that the thoughts . . . may be revealed: This fits with the passage in John 15:22—“now they have no cloak for their sin.” It is not that the thoughts of the wicked will be revealed to God who already knows each person’s thoughts. Rather, Jesus will take away the cloak of sin so that evil doers are exposed to public gaze, including those who contemplate wickedness. Moreover, the sense of Simeon’s words points to thoughts as the springboard for evil acts (see 5:22; 6:8; the Note on 24:38).

Our only record of the man Simeon appears in these verses. Attempts to link him to other known persons do not succeed, though he may be tied both to the temple and the Sanhedrin at Jerusalem. Although we usually assume that he is an elderly person because of his reference to death, he need not be very old.

Simeon’s entry into the story allows Luke to stress a number of important characteristics of this man which fit into a gospel framework. First, Luke emphasizes that Simeon is “just and devout,” aspects that mirror a high degree of self-control and noble motivation. The result of Simeon’s righteousness, of course, is that “the Holy Ghost was upon him” (2:25). This portrait of Simeon’s life of devotion, brought forward in just a few words, underscores what is available to anyone who receives the newborn Messiah. Moreover, to Simeon, who has consciously cultivated a life of devotion, comes the spirit of prophecy, allowing him to reveal something of the Savior’s future. That future will include touching not only Israelites but also Gentiles with the message of salvation. This universalism underlies Luke’s two volumes, his Gospel and the Acts. In addition, according to Simeon’s prophecy, the future will include conflicts that will dog Jesus’ footsteps throughout his ministry. Further, Simeon becomes a witness of the first rank, both before the infant’s parents and before others, that God has initiated a special effort among his children.

The hymn of Simeon (2:29–32), called Nunc Dimittis (“now thou dismissest”), joins those of Mary (see 1:46–55) and Zacharias (see 1:68–79) to form an interesting pattern. In a literary sense, it stands at the end of a cycle that begins with promise (the hymn of Mary) and continues with fulfillment in the birth of John (the song of Zacharias) and ends with a “response of praise” on the lips of Simeon. Such praise, of course, also bursts forth in the song of the angels (see 2:13–14) and in the words of Anna (see 2:38). But the angels’ song comes from heaven and Anna’s praise stands unrecorded. Thus, Simeon’s earthly hymn of praise neatly ties off Luke’s presentation of the initial events of God’s imminent salvation, as seen by mortals, showing them to have come to one Simeon who is guided by God’s Spirit.

Simeon’s hymn also discloses threads that tie back to Isaiah’s four Servant Songs (see Isa. 42:1–4; 49:1–6; 50:4–9; 52:13–53:12). First identified by Bernhard Duhm in 1892, these songs point expectantly to God’s servant who will bring the reign of righteousness with him as well as bear away the sins of his people. Hence, the Lord’s servant functions as both King and Messiah, aspects that fit within Luke’s larger purposes. This explains why Simeon’s hymn is important to record.

Anna (Luke 2:36–38)

36 And Anna was a prophetess, a daughter of Phanuel, from the tribe of Asher. She was advanced in days, having lived with her husband seven years from her maidenhood. 37 And she was a widow until the age of eighty-four, who did not depart from the temple since she served by fasts and prayers night and day. 38 And she came that same hour, and praised God, and spoke about him to all those waiting for the redemption of Jerusalem.

2:36 Anna: A variant form of Hannah, the name is one more piece that ties back to the earlier Old Testament account of Hannah and her son Samuel (see 1 Sam. 1:1–2:11, 18–21).

a prophetess: Luke’s term elevates Anna and indicates the respect that she enjoys among her peers. Other women known to enjoy the spirit of prophecy are Deborah (see Judg. 4:4), Hulda (see 2 Kgs. 22:14), and the four daughters of Philip (see Acts 21:9).

she was of a great age: The expression is literally “she had advanced many days.” For the term “days” as a common biblical way to describe old age, see Genesis 5:4–5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, etc.

had lived with an husband seven years: Evidently, Anna’s husband dies a mere seven years after their marriage, leaving her a widow, perhaps before she is twenty years old, depending on her age at marriage (see 2:37). One senses the pain of her loss within these words.

2:37 a widow: In a sense, Anna stands for all the widows whom Luke’s Gospel will feature, women of goodness whose place and status in this world are regularly under threat (see 4:25–26; 7:11–15; 18:2–6; 20:47; 21:1–4).

about fourscore and four years: Luke apparently sets out Anna’s age when she meets Joseph and Mary to be eighty-four, though the number may point to the years that have passed since her husband died. In either case, Luke firms up his comment that “she was of a great age” (2:36). A certain symbolism may rest undiscovered here because eighty-four is the product of twelve and seven, two numbers that carry rich metaphorical meanings.

departed not from the temple: The word for temple here is hieron and refers to the larger complex (see also 2:27, 46; 4:9; 18:10; the Note on 19:45) rather than to the sanctuary (see 1:21, 22; 23:45; the Note on 1:9). Commentators are unsure whether Anna is somehow a permanent resident within the temple precincts or whether she comes from a nearby home every day. Residency at the temple for women is not attested in Jewish sources. In any event, she is likely praying inside the Court of the Women, where she enjoys a clear view of the great altar and sanctuary through the Nicanor Gate. According to a second-century text called Protevangelium of James, in verses 7:1–8:1, the parents of Mary bring her as a three-year-old child to the temple, where she remains in residence until she is twelve, agreeing with other sources that up to eighty-two girls serve as weavers for the veil of the temple. But we should treat this story about young Mary as legendary.

prayers night and day: This reference to the twice-daily sacrifice and prayer services at the temple makes a case for Luke as a reasonably accurate recorder of Jewish customs. The daily services, of course, include lighting the incense in the sanctuary (see 1:9).

2:38 she coming in that instant: As with his notice of Simeon, Luke wants us to understand that Anna comes to this spot by the aid of the Spirit, a point made firm by calling her “a prophetess” (2:36). Moreover, she arrives at the end of Simeon’s words, meaning that she does not take her clue about the child from him. Her witness stands independent.

gave thanks likewise: Though we do not possess Anna’s words, the statement draws together her response and that of Simeon, placing them on the same ground. Hers too is evidently an expression of praise, a meaning inherent in the Greek verb anthomologeomai.

spake of him to all them that looked for redemption: Two matters become clear. First, Anna becomes a witness of God’s “redemption” through his son, essentially mirroring the other privileged observers. Second, many in her society are looking expectantly for God’s promised redemption. Her words to them will speak to a deeply felt need.

redemption in Jerusalem: Whereas the texts on which the King James Version is based include the preposition “in” (Greek en ), some of the best early manuscripts read “redemption of Jerusalem,” an expression that turns a different light on how and where redemption is to occur. If redemption is to take place in Jerusalem, then we look to the last days and hours of Jesus’ ministry, though his deepest suffering and his death occur outside the city walls, in Gethsemane and on Golgotha. If redemption is to be of Jerusalem, then the city represents all Israelites, as hinted at in Moroni 10:31—“awake, and arise from the dust, O Jerusalem; . . . that the covenants of the Eternal Father which he hath made unto thee, O house of Israel, may be fulfilled.”

2:39 when they had performed all things according to the law of the Lord: Luke’s summary ties the actions of Mary and Joseph to others who are law-abiding citizens, one of his points of emphasis (see the introduction to chapter 1, section C). In addition, he stresses that they keep all the law. Further, the law belongs to the domain of the Lord; it is divine in character.

they returned into Galilee, to . . . Nazareth: Luke’s report omits the flight into Egypt (see Matt. 2:13–15). We do not know whether he chooses not to include this event or whether he does not know about it. In either instance, the family in time moves to Nazareth, where Joseph probably finds work during the reconstruction of the city of Sepphoris, the main center of Galilee, rather than staying in the area of Jerusalem where he can earn a much higher wage for his skills. Sepphoris lies a mere three miles northwest of Nazareth. Its citizens revolt after Herod dies in 4 Bc and are soon subdued by Roman legionnaires from Syria under the command of P. Quinctilius Varus, legate of Syria. During the battle, Sepphoris burns but is later rebuilt. Naturally, Joseph’s building skills are then in demand. We surmise that Joseph takes Jesus with him to work in the town, thus allowing the youth to learn Greek from Greek-speaking foremen. This circumstance explains why, in the trial before Pilate, Jesus and Pilate do not need an interpreter (see the Note on 23:3).

The temple serves as the anchor in the series of stories that begin with the visit of Mary and Joseph to perform the required sacrifices and to offer the redemption gift following the birth of Jesus. Those accounts finally lead us to Anna who is known openly in the city as one associated with the temple and its services. Luke’s record, of course, will bring temple-related activities to a conclusion in chapter 2 with the story of Jesus’ Passover visit at age twelve (see 2:40–52). But a major focus of this chapter rests on events during one momentous day, one on which Jesus’ parents present the Christ child at the temple. Before the end of that day, God leads both Simeon and Anna to the child and inspires them in their praise. Anna’s known gift of prophecy (see 2:36), here manifested within the temple complex, confers on the infant Jesus a visible, palpable stamp of divine approval. To be sure, other events will do the same, but Anna’s arrival and subsequent witness borne to others will carry weight into the minds of bystanders.

As with Simeon, Anna’s praise arises within sacred precincts, linking the unfolding story of the Christ child more tightly to holiness. Her praise, too, rounds off the sense of promise and fulfillment that weave their way through the songs of Mary and Zacharias and the angels. Further, her status as a respected woman elevates the unfurling events, conferring on them a dignity and a feminine quality that they otherwise lack.

Anna’s name brings us back to the question of whether the story of Hannah influences Luke’s narrative. Even if it does, this does not mean that we should see Anna as fictional, as a mere symbol. Even if much in Luke’s narrative here links back to Hannah and her son Samuel, it is plain that Anna is a real person who comes by inspiration to where Joseph and Mary are. That said, summarizing statements about Jesus seem to tie to similar observations written about Samuel (see 1 Sam. 2:19, 26; 3:19). The statements about Jesus read: “the child grew, and waxed strong in spirit, filled with wisdom: and the grace of God was upon him” (2:40) and “Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man” (2:52). As an additional piece, Mary’s song as she enters the home of Elisabeth resembles that of Hannah (see 1 Sam. 2:1–10; Luke 1:46–55). And, of course, both Samuel and Jesus come as children of promise, dedicated to God.

- Español NEW

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple facts for kids

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (or in the temple ) is an early episode in the life of Jesus Christ , describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem , that is celebrated by many churches 40 days after Christmas on Candlemas , or the "Feast of the Presentation of Jesus". The episode is described in chapter 2 of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament . Within the account, "Luke's narration of the Presentation in the Temple combines the purification rite with the Jewish ceremony of the redemption of the firstborn (Luke 2:23–24)."

In the Eastern Orthodox Church , the Presentation of Jesus at the temple is celebrated as one of the twelve Great Feasts, and is sometimes called Hypapante ( Ὑπαπαντή , "meeting" in Greek).

The Orthodox Churches which use the Julian Calendar celebrate it on 15 February, and the Armenian Church on 14 February.

In Western Christianity , the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord is also known by its earlier name as the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin or the Meeting of the Lord . In some liturgical calendars, Vespers (or Compline) on the Feast of the Presentation marks the end of the Epiphany season , also (since the 2018 lectionary) in the Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland (EKD). In the Church of England , the mother church of the Anglican Communion, the Presentation of Christ in the Temple is a Principal Feast celebrated either on 2 February or on the Sunday between 28 January and 3 February. In the Roman Catholic Church , especially since the time of Pope Gelasius I (492-496) who in the fifth century contributed to its expansion, the Feast of the Presentation is celebrated on 2 February.

In the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Church, the episode was also reflected in the once-prevalent custom of churching of women forty days after the birth of a child. The Feast of the Presesentation of the Lord is in the Roman Rite also attached to the World Day of Consecrated Life.

Name of the celebration

Western christianity, eastern christianity, relation to other celebrations, traditions and superstitions.

The event is described in the Gospel of Luke ( Luke 2:22–40 ). According to the gospel, Mary and Joseph took the Infant Jesus to the Temple in Jerusalem forty days (inclusive) after His birth to complete Mary's ritual purification after childbirth, and to perform the redemption of the firstborn son , in obedience to the Torah ( Leviticus 12 , Exodus 13:12–15 , etc.). Luke explicitly says that Joseph and Mary take the option provided for poor people (those who could not afford a lamb; Leviticus 12:8 ), sacrificing "a pair of turtledoves , or two young pigeons." Leviticus 12:1–4 indicates that this event should take place forty days after birth for a male child, hence the Presentation is celebrated forty days after Christmas.

Upon bringing Jesus into the temple, they encountered Simeon. The Gospel records that Simeon had been promised that "he should not see death before he had seen the Lord's Christ " ( Luke 2:26 ). Simeon then uttered the prayer that would become known as the Nunc Dimittis , or Canticle of Simeon, which prophesied the redemption of the world by Jesus:

"Lord, now let your servant depart in peace, according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for glory to your people Israel". ( Luke 2:29–32 ).

Simeon then prophesied to Mary: "Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign that is spoken against (and a sword will pierce through your own soul also), that thoughts out of many hearts may be revealed. ( Luke 2:34–35 ).

The elderly prophetess Anna was also in the Temple, and offered prayers and praise to God for Jesus, and spoke to everyone there of His importance to redemption in Jerusalem ( Luke 2:36–38 ).

Cornelius a Lapide comments on Mary and Joseph sacrificing a pair of turtledoves: "...because they were poor; for the rich were obliged to give in addition to this a lamb for a holocaust. Although the three kings had offered to Christ a great quantity of gold, still the Blessed Virgin, zealously affected towards poverty, accepted but little of it, that she might show her contempt of all earthly things. The couple offered two turtledoves or two pigeons (Luke 2:24) presumably because they could not afford a lamb.

Liturgical celebration

In addition to being known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple , other traditional names include Candlemas, the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin, and the Meeting of the Lord.

The date of Candlemas is established by the date set for the Nativity of Jesus , for it comes forty days afterwards. Under Mosaic law as found in the Torah , a mother who had given birth to a boy was considered unclean for seven days; moreover she was to remain for three and thirty days "in the blood of her purification." Candlemas therefore corresponds to the day on which Mary, according to Jewish law, should have attended a ceremony of ritual purification ( Leviticus 12:2–8 ). The Gospel of Luke 2:22–39 relates that Mary was purified according to the religious law, followed by Jesus' presentation in the Jerusalem temple, and this explains the formal names given to the festival, as well as its falling 40 days after the Nativity.

In the Roman Catholic Church, it is known as the Presentation of the Lord in the liturgical books first issued by Paul VI , and as the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary in earlier editions . In the Eastern Orthodox Church and Greek Catholic Churches ( Eastern Catholic Churches which use the Byzantine rite), it is known as the Feast of the Presentation of our Lord, God, and Savior Jesus Christ in the Temple or as The Meeting of Our Lord, God and Saviour Jesus Christ .

In the churches of the Anglican Communion , it is known by various names, including The Presentation of Our Lord Jesus Christ in The Temple (Candlemas) ( Episcopal Church ), The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, and The Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary ( Anglican Church of Canada ), The Presentation of Christ in the Temple (Candlemas) ( Church of England ), and The Presentation of Christ in the Temple ( Anglican Church of Australia ).

It is known as the Presentation of Our Lord in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod observes 2 February as The Purification of Mary and the Presentation of Our Lord. In some Protestant churches, the feast is known as the Naming of Jesus.

Candlemas is a northern European name for the feast because of the procession with lighted candles at the mass on this day, reflecting Simeon's proclamation of "a light for revelation to the Gentiles", which, in turn, echoes Isaiah 49:6 in the second of the "servant of the Lord" oracles.

Traditionally, Candlemas had been the last feast day in the Christian year that was dated by reference to Christmas . It is another "epiphany" type feast as Jesus is revealed as the messiah by the canticle of Simeon and the prophetess Anna. It also fits into this theme, as the earliest manifestation of Jesus inside the house of his heavenly Father. Subsequent moveable feasts are calculated with reference to Easter .

Candlemas occurs 40 days after Christmas.

Traditionally, the Western term "Candlemas" (or Candle Mass) referred to the practice whereby a priest on 2 February blessed beeswax candles for use throughout the year, some of which were distributed to the faithful for use in the home. In Poland the feast is called Święto Matki Bożej Gromnicznej (Feast of Our Lady of Thunder candles). This name refers to the candles that are blessed on this day, called gromnice, since these candles are lit during (thunder) storms and placed in windows to ward off storms.

This feast has been referred to as the Feast of Presentation of the Lord within the Roman Catholic Church since the liturgical revisions of the Second Vatican Council , with references to candles and the purification of Mary de-emphasised in favor of the Prophecy of Simeon the Righteous. Pope John Paul II connected the feast day with the renewal of religious vows. In the Roman Catholic Church, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple is the fourth Joyful Mystery of the Rosary.

In the Liturgy of the Hours, the Marian antiphon Alma Redemptoris Mater is used from Advent through 2 February, after which Ave Regina Caelorum is used through Good Friday.

In the Byzantine tradition practiced by the Eastern Orthodox , the Meeting of the Lord is unique among the Great Feasts in that it combines elements of both a Great Feast of the Lord and a Great Feast of the Theotokos ( Mother of God ). It has a forefeast of one day, and an afterfeast of seven days. However, if the feast falls during Cheesefare Week or Great Lent , the afterfeast is either shortened or eliminated altogether.

The holiday is celebrated with an all-night vigil on the eve of the feast, and a celebration of the Divine Liturgy the next morning, at which beeswax candles are blessed. This blessing traditionally takes place after the Little Hours and before the beginning of the Divine Liturgy (though in some places it is done after). The priest reads four prayers, and then a fifth one during which all present bow their heads before God. He then censes the candles and blesses them with holy water. The candles are then distributed to the people and the Liturgy begins.

It is because of the biblical events recounted in the second chapter of Luke that the Churching of Women came to be practiced in both Eastern and Western Christianity. The usage has mostly died out in the West, except among Western Rite Orthodoxy, very occasionally still among Anglicans , and Traditionalist Catholics, but the ritual is still practiced in the Orthodox Church. In addition, babies, both boys and girls are taken to the Church on the fortieth day after their birth in remembrance of the Theotokos and Joseph taking the infant Jesus to the Temple.

Some Christians observe the practice of leaving Christmas decorations up until Candlemas.

In the Eastern and Western liturgical calendars the Presentation of the Lord falls on 2 February, forty days (inclusive) after Christmas . In the Church of England it may be celebrated on this day, or on the Sunday between 28 January and 3 February. This feast never falls in Lent; the earliest that Ash Wednesday can fall is 4 February, for the case of Easter on 22 March in a non-leap year. However, in the Tridentine rite, it can fall in the pre-Lenten season if Easter is early enough, and "Alleluia" has to be omitted from this feast's liturgy when that happens.

In Swedish and Finnish Lutheran Churches, Candlemas is (since 1774) always celebrated on a Sunday , at earliest on 2 February and at latest on 8 February, except if this Sunday happens to be the last Sunday before Lent , i.e. Shrove Sunday or Quinquagesima ( Swedish : Fastlagssöndagen , Finnish : Laskiaissunnuntai ), in which case Candlemas is celebrated one week earlier.

In the Armenian Apostolic Church , the Feast, called "The Coming of the Son of God into the Temple" ( Tiarn'ndaraj , from Tyarn- , "the Lord", and -undarach "going forward"), is celebrated on 14 February. The Armenians do not celebrate the Nativity on 25 December, but on 6 January, and thus their date of the feast is 40 days after that: 14 February. The night before the feast, Armenians traditionally light candles during an evening church service, carrying the flame out into the darkness (symbolically bringing light into the void) and either take it home to light lamps or light a bonfire in the church courtyard.

The Feast of the Presentation is among the most ancient feasts of the Church. Celebration of the feast dates from the fourth century in Jerusalem. There are sermons on the Feast by the bishops Methodius of Patara († 312), Cyril of Jerusalem († 360), Gregory the Theologian († 389), Amphilochius of Iconium († 394), Gregory of Nyssa († 400), and John Chrysostom († 407).

The earliest reference to specific liturgical rites surrounding the feast are by the intrepid Egeria , during her pilgrimage to the Holy Land (381–384). She reported that 14 February was a day solemnly kept in Jerusalem with a procession to Constantine I 's Basilica of the Resurrection, with a homily preached on Luke 2:22 (which makes the occasion perfectly clear), and a Divine Liturgy. This so-called Itinerarium Peregrinatio ("Pilgrimage Itinerary") of Egeria does not, however, offer a specific name for the Feast. The date of 14 February indicates that in Jerusalem at that time, Christ's birth was celebrated on 6 January, Epiphany . Egeria writes for her beloved fellow nuns at home:

XXVI. "The fortieth day after the Epiphany is undoubtedly celebrated here with the very highest honor, for on that day there is a procession, in which all take part, in the Anastasis, and all things are done in their order with the greatest joy, just as at Easter. All the priests, and after them the bishop, preach, always taking for their subject that part of the Gospel where Joseph and Mary brought the Lord into the Temple on the fortieth day, and Symeon and Anna the prophetess, the daughter of Phanuel, saw him, treating of the words which they spake when they saw the Lord, and of that offering which his parents made. And when everything that is customary has been done in order, the sacrament is celebrated, and the dismissal takes place."

About AD 450 in Jerusalem, people began the custom of holding lighted candles during the Divine Liturgy of this feast day. Originally, the feast was a minor celebration. But then in 541, a terrible plague broke out in Constantinople , killing thousands. The Emperor Justinian I , in consultation with the Patriarch of Constantinople , ordered a period of fasting and prayer throughout the entire Empire. And, on the Feast of the Meeting of the Lord, arranged great processions throughout the towns and villages and a solemn prayer service ( Litia ) to ask for deliverance from evils, and the plague ceased. In thanksgiving, in 542 the feast was elevated to a more solemn celebration and established throughout the Eastern Empire by the Emperor.

In Rome , the feast appears in the Gelasian Sacramentary , a manuscript collection of the seventh and eighth centuries associated with Pope Gelasius I . There it carries for the first time the new title of the feast of Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Late in time though it may be, Candlemas is still the most ancient of all the festivals in honor of the Virgin Mary. The date of the feast in Rome was 2 February because the Roman date for Christ's nativity had been 25 December since at least the early fourth century.

Though modern laymen picture Candlemas as an important feast throughout the Middle Ages in Europe , in fact it spread slowly in the West; it is not found in the Lectionary of Silos (650) nor in the Calendar (731–741) of Sainte-Geneviève of Paris .

The tenth-century Benedictional of St. Æthelwold , bishop of Winchester , has a formula used for blessing the candles. Candlemas did become important enough to find its way into the secular calendar. It was the traditional day to remove the cattle from the hay meadows, and from the field that was to be ploughed and sown that spring. References to it are common in later medieval and early Modern literature; Shakespeare 's Twelfth Night is recorded as having its first performance on Candlemas Day 1602. It remains one of the Scottish quarter days, at which debts are paid and law courts are in session.

The Feast of the Presentation depends on the date for Christmas : As per the passage from the Gospel of Luke ( Luke 2:22–40 ) describing the event in the life of Jesus, the celebration of the Presentation of the Lord follows 40 days after. The blessing of candles on this day recalls Simeon's reference to the infant Jesus as the "light for revelation to the Gentiles" ( Luke 2:32 ).

Modern Pagans believe that Candlemas is a Christianization of the Gaelic festival of Imbolc , which was celebrated in pre-Christian Europe (and especially the Celtic Nations) at about the same time of year. Imbolc is called "St. Brigid's Day" or "Brigid" in Ireland. Both the goddess Brigid and the Christian Saint Brigid—who was the Abbess of Kildare —are associated with sacred flames, holy wells and springs, healing, and smithcraft. Brigid is a virgin, yet also the patron of midwives. However, a connection with Roman (rather than Celtic or Germanic) polytheism is more plausible, since the feast was celebrated before any serious attempt to expand Christianity into non-Roman countries.

In Irish homes, there were many rituals revolving around welcoming Brigid into the home. Some of Brigid's rituals and legends later became attached to Saint Brigid, who was seen by Celtic Christians as the midwife of Christ and "Mary of the Gael". In Ireland and Scotland she is the "foster mother of Jesus." The exact date of the Imbolc festival may have varied from place to place based on local tradition and regional climate. Imbolc is celebrated by modern Pagans on the eve of 2 February, at the astronomical midpoint, or on the full moon closest to the first spring thaw.

Frederick Holweck, writing in the Catholic Encyclopædia says definite in its rejection of this argument: "The feast was certainly not introduced by Pope Gelasius to suppress the excesses of the Lupercalia," (referencing J.P. Migne , Missale Gothicum , 691) The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica agrees: the association with Gelasius "has led some to suppose that it was ordained by Pope Gelasius I in 492 as a counter-attraction to the pagan Lupercalia; but for this there is no warrant." Since the two festivals are both concerned with the ritual purification of women, not all historians are convinced that the connection is purely coincidental. Gelasius certainly did write a treatise against Lupercalia, and this still exists.

Pope Innocent XII believed Candlemas was created as an alternative to Roman Paganism, as stated in a sermon on the subject:

Why do we in this feast carry candles? Because the Gentiles dedicated the month of February to the infernal gods, and as at the beginning of it Pluto stole Proserpine , and her mother Ceres sought her in the night with lighted candles, so they, at the beginning of the month, walked about the city with lighted candles. Because the holy fathers could not extirpate the custom, they ordained that Christians should carry about candles in honor of the Blessed Virgin; and thus what was done before in the honor of Ceres is now done in honor of the Blessed Virgin.

There is no contemporary evidence to support the popular notions that Gelasius abolished the Lupercalia, or that he, or any other prelate, replaced it with the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary .

In Armenia, celebrations at the Presentation have been influenced by pre-Christian customs, such as: the spreading of ashes by farmers in their fields each year to ensure a better harvest, keeping ashes on the roof of a house to keep evil spirits away, and the belief that newlywed women needed to jump over fire to purify themselves before getting pregnant. Young men will also leap over a bonfire.

The tradition of lighting a candle in each window is not the origin of the name "Candlemas", which instead refers to a blessing of candles.

On the day following Candlemas, the feast of St. Blaise is celebrated. It is connected to the rite of Blessing of the Throats, which is, for to be available to reach more people, also often transferred after the Mass of the Presentation of the Lord or even bestowed on both feasts. By coincidence, the Blessing of the Throats is bestowed with crossed candles.

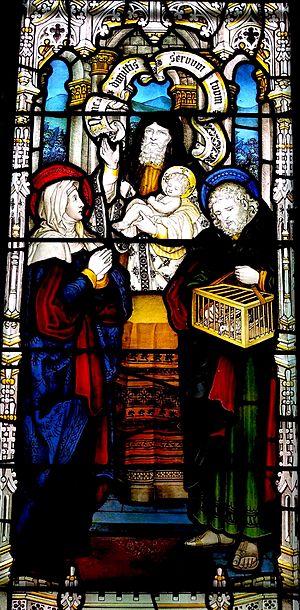

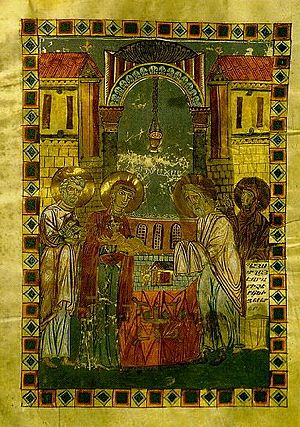

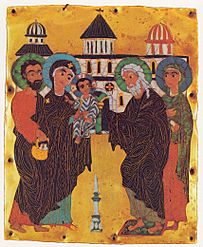

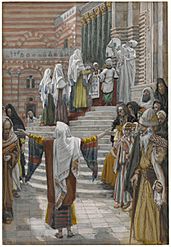

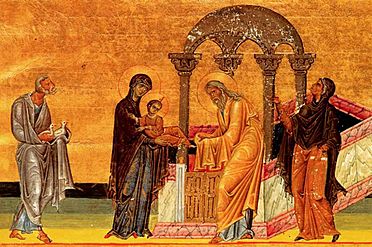

The event forms a usual component of extensive cycles of the Life of Christ and also of the Life of the Virgin . Early images concentrated on the moment of meeting with Simeon.

In the West, beginning in the 8th or 9th century, a different depiction at an altar emerged, where Simeon eventually by the Late Middle Ages came to be shown wearing the elaborate vestments attributed to the Jewish High Priest, and conducting a liturgical ceremony surrounded by the family and Anna. In the West, Simeon is more often already holding the infant, or the moment of handover is shown; in Eastern images the Virgin is more likely still to hold Jesus. In the Eastern Churches this event is called the Hypapante .

Simeon's comment that "you yourself a sword will pierce" gave rise to a subset iconography of the Sorrowful Mother.

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple , 12th century cloisonné enamel icon from Georgia

Presentation of Christ in the Temple, from the Sherbrooke Missal

James Tissot , The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple ( La présentation de Jésus au Temple ), Brooklyn Museum

Stained glass window at St. Michael's Cathedral (Toronto) depicts Infant Jesus at the Temple