How long should a case study be?

How Long Should a Case Study Be?

When it comes to writing a case study, one of the most common questions that arise is "how long should it be?" In this article, we will explore the ideal length of a case study, provide guidance on how to structure it, and offer tips on how to make it engaging and effective.

Direct Answer: How Long Should a Case Study Be?

The answer to this question depends on the purpose and goals of the case study, as well as the audience it is intended for. However, here are some general guidelines:

- For Academia or Research Purposes: 10-20 pages (25-50 double-spaced pages) is a common range for academic case studies. This is because academic case studies are often required to provide in-depth analysis, critique, and original research findings, which may require a more comprehensive approach.

- For Business or Marketing Purposes: 2-5 pages (5-10 double-spaced pages) is a common range for business case studies. This is because these case studies are often designed to promote a product or service, and are intended to be brief and concise, conveying the essential information in a clear and concise manner.

- For Healthcare or Medical Purposes: 1-3 pages (2.5-7.5 double-spaced pages) is a common range for healthcare-related case studies. This is because medical case studies often require a detailed presentation of the patient’s symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment, which may be too lengthy for a short case study.

Factors to Consider When Determining the Length of Your Case Study

When deciding how long your case study should be, consider the following factors:

- Purpose: What is the primary goal of the case study? Is it to educate, persuade, or demonstrate the effectiveness of a product or service?

- Audience: Who is your target audience? Are they experts in the field or general readers?

- Content: How much information do you need to convey to achieve the purpose of the case study? Are there complex technical details that need to be included?

- Format: Will the case study be presented in a written narrative, or in a more visual format, such as infographics or videos?

- Word Count: Be realistic about the time and effort required to write a comprehensive case study. A realistic goal is to aim for a word count of 500-2000 words, depending on the purpose and audience.

Structuring Your Case Study

A well-structured case study should have the following components:

- Introduction: Introduce the case, provide background information, and establish the purpose of the study.

- Background: Provide context and background information on the case, including relevant data and statistics.

- Methodology: Describe the methods used to collect and analyze data.

- Results: Present the findings, highlighting key results and insights.

- Discussion: Interpret the results, relating them to the research question or hypothesis.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main findings and implications.

- References: List sources used in the study.

Tips for Writing an Engaging and Effective Case Study

- Focus on the Key Findings: Highlight the most significant and relevant results, and use visual aids, such as charts and tables, to support your findings.

- Use Clear Language: Avoid using jargon or technical terms that may be unfamiliar to non-experts.

- Use Storytelling Techniques: Use narratives, anecdotes, and relatable examples to make the case study more engaging and memorable.

- Use Visual Aids: Incorporate images, graphs, and charts to break up the text and illustrate complex concepts.

- Edit and Revise: Review and edit the case study carefully to ensure accuracy, clarity, and coherence.

In conclusion, the length of a case study depends on the purpose, audience, and format. By considering the factors outlined above, you can determine the ideal length for your case study. Remember to structure your case study clearly, focus on the key findings, and use engaging language to make it an effective and memorable read.

Table 1: Case Study Length Guidelines

Table 2: Case Study Structure Guidelines

I hope this article helps you in determining the ideal length and structure of your case study, as well as provides you with some valuable tips for writing an engaging and effective case study.

- How to make engaging reels on Instagram?

- How to recover old Gmail account?

- How can You save a video on Instagram?

- Does AirPods have Microphone?

- How to share a pdf document on Facebook?

- How to save an email as a draft in Outlook?

- How to dispute Apple Pay transaction?

- How to get to clipboard on iPhone?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How Long Should A Case Study Be?

What’s the ideal case study length.

If your case study is too long… your leads might not look at it, never mind read or watch it.

But if a case study is too short… it may lack the details it needs to persuade leads that you’re the one and best choice for them.

So how long should your case study be?

Fortunately, research gives us some guidelines for case study length on the written side of things.

According to a DocSend report of 34 million content interactions , for example, case studies should be two to five pages in length.

They advise:

“Try to get [your text] into a piece of sales content just 2-5 pages in length, total. Based on our analysis, completion rate for case studies of that length was highest across all content types….”

Did you catch that last bit? Case studies in that range have the highest completion rate over ANY content type shared with DocSend —blog posts, brochures, whitepapers… the works!

Still, two to five pages is a *very* broad range. And what does a ‘page’ mean? Does that mean your case study should be 600 words? 1,200? 2,000? Does word count even matter?

Unfortunately, the only answer to this question is: it depends! Different lengths can play better or worse in different scenarios.

Let’s unpack what that looks like, practically—and how you can arrive at the right decision on length for your use case.

Your case study must be long enough to tell the story

One factor to consider when deciding on the “right” length for your case study is the story you want to tell.

As any campfire enthusiast will tell you, some great stories are long; others are short.

For example, we recently completed a case study for a client that came in at a whopping 1,838 words.

Why so long?

Quite simply, the story was complex, and the writer needed all 1,838 words to tell it.

This high-profile project involved six different creative teams, each playing a different role—all of whom needed to be spotlighted.

The project also garnered a lot of media attention and some jaw-dropping results, which we also wanted to hit on.

In short, everything in that case study needed to be there.

In contrast, the same writer wrote a case study for a different project that clocked in at a brisk 650 words. Here, the story was simpler—with fewer actors and a more straightforward solution—and 650 words was more than enough.

In summary, your case studies should be as long as they need to be to tell the story.

Which isn’t a terribly helpful guideline, I know.

So let’s look at a couple other factors you should consider when deciding on length.

Align case study length with your target audience

You can look at case studies through two different (although related) lenses: 1) whom you’re targeting and 2) how you’ll use them.

Let’s look at targeting first.

We can agree that executive decision makers want different things from your case studies than product or service implementers.

Executive decision makers aren’t particularly interested in the nitty gritty details of your projects. They want the highlights and the results.

After all, they’re not the ones who will be implementing and managing the solution. Generally speaking, they just want to know that the product or solution will succeed. And besides, they simply don’t have time to wade into all the details.

So a shorter case study, with descriptive titles and bullet points, gives this target audience what it wants.

In contrast, implementers—or those making buy/don’t buy recommendations to the executive team—ARE interested in the details. They’re going to be the ones implementing the product or solution so they want to know everything about the strategy, steps, delivery and more.

They want a blow-by-blow account of what happened. What went well? What went wrong? How did you adapt? What was the thinking behind your decisions? What were you like to work with?

These details come forward in the solution section of a case study —so that’s where you’ll see the greatest variance in case study length.

Align case study length with your sales funnel

Another factor to consider is how you will use your case studies.

Will you use them at the top, middle or bottom of your sales/marketing funnel?

Case studies aimed at top-of-funnel leads can often be shorter. You want something that leads can absorb and scan quickly. After all, your goal at this juncture is to raise awareness of your service or product.

At this stage, leads are still researching and considering their options. Giving them all the details will be fruitless and may even confuse them.

Similarly, if you’re doing cold outreach, a short case study often makes more sense than a long one.

However, there are some exceptions . In the case of an ad campaign, for example, a longer case study might be the way to go—even though you’re marketing to top-of-funnel leads.

Why? Because ad campaigns are often targeted at specific pain points or “how to” type processes, and you’ll need a longer case study to delve into how your product or service solved that pain point.

Continuing with the same logic, case studies aimed at the middle or bottom of the sales/marketing funnel can usually be longer and more detailed.

At this later stage, leads have narrowed their list of potential vendors and are ready to get into the weeds with you.

Again, you want to give them that longer solution section that walks through each stage of the implementation process.

Here, a five-page case study (or even longer) might be what’s needed to move a lead down your funnel.

Best option: Tell the same story in different formats

So some case studies should be short; others should be long, depending on whom you’re targeting and how you’ll use them.

But what if you want to target different audiences at different stages of your funnel?

In this scenario, your best option is to tell the same story in different formats.

Let me use a food analogy to explain.

Sometimes you’re hungry for an entire meal. Other times, you want a snack.

If you’re uncertain, you may only take a nibble. If you like that nibble, you might try a bite. If that tastes good, you may move on to eat the entire meal.

It’s the same with case studies.

A story can be as short as a testimonial when a pinch of proof is all that’s needed.

But the same story can be told as a full-blown written or video case study when a meal is called for.

These nibbles, bites, snacks and meals can also work together.

A short 15-second video might gain attention for a larger piece that tells the full story and gets into the “how” of a project.

A two-sentence teaser in a newsletter might cause a lead to click through to your longer case study to get all the details.

Telling the same study in all these multiple formats might sound like a slog—but, it’s not at all.

Most of the work in creating a case study is in devising strategy, getting buy in, performing research and conducting great interviews.

Once you’ve navigated these challenges, telling the story in multiple ways is easier.

You don’t have to start with the longest asset (although that’s what we usually recommend).

Once you have it, creating other, shorter versions is much easier than starting from scratch.

(That’s why we offer a discount for case study packages that include different formats of the same customer success story.)

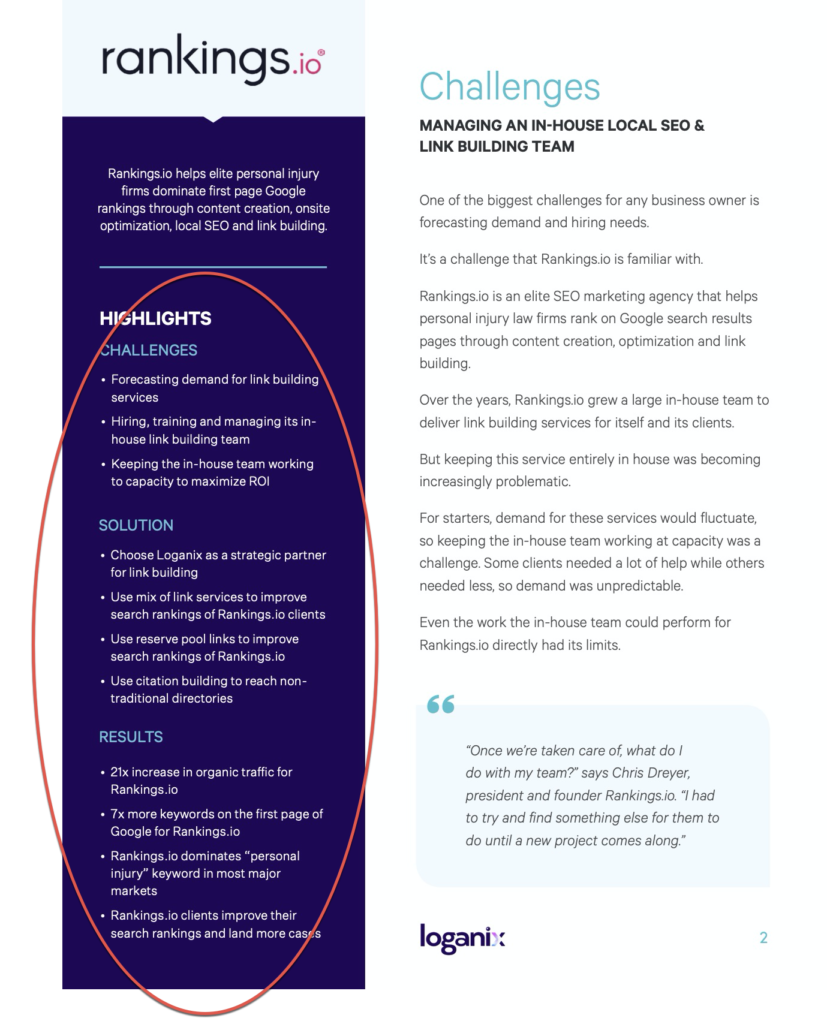

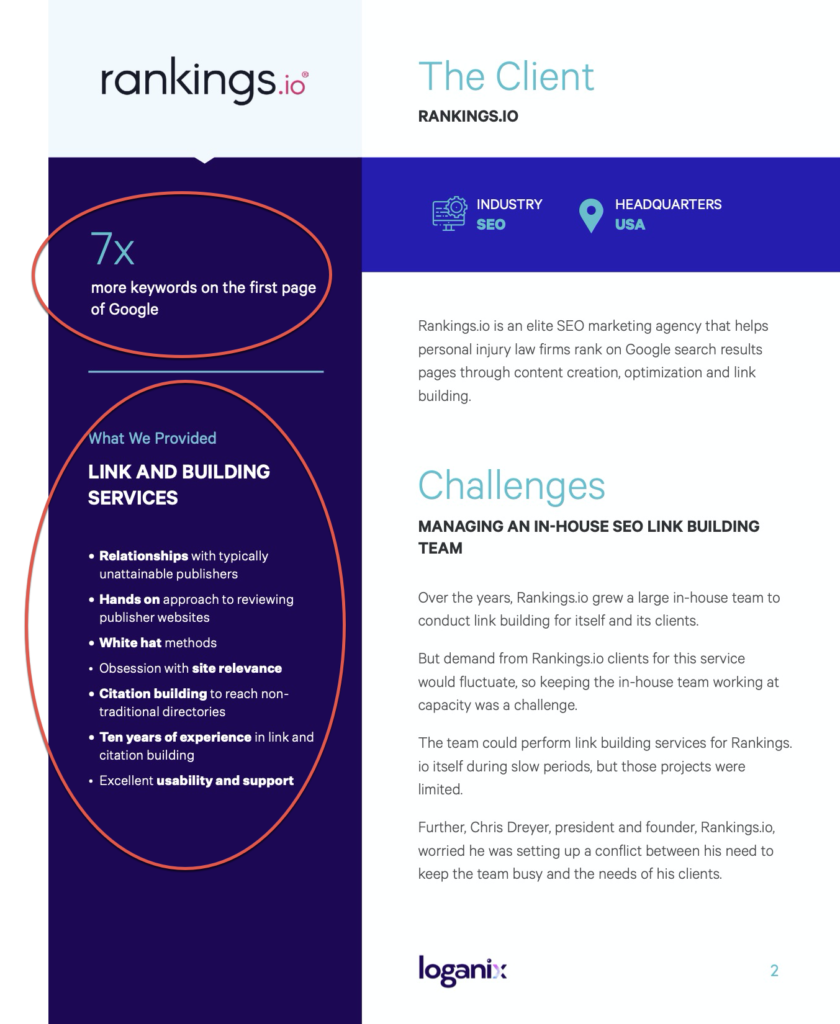

Example: Loganix

To better understand these formats, let’s look at one customer success story we told six different ways:

Narrative case study

Snapshot case study, html teaser, image cards.

This is the story of Loganix and its customer Rankings.io.

Loganix provides citation building and local search marketing solutions to agencies and publishers around the world.

Its customer, Rankings.io, helps elite personal injury firms dominate first page Google rankings.

In this customer success story, Loganix helped Rankings.io get seven times more keywords on the first page of Google through its citation building services.

Let’s start with the narrative case study for this success story.

Here’s the cover page:

As you might expect, this detailed case study describes the challenges, solutions and results.

But the bulk of the case study is in the solutions section , where we really dig into the details of why and how Loganix was able to help Rankings.io obtain such great results.

This section details key differentiators that made all the difference for this project , such as Loganix’s strong relationships with publishers and its hands-on approach.

Why do we go into so much detail into the WHY and HOW of this customer success story?

Because this case study format is designed for those who will be working closely with Loganix—or those recommending whether to choose Loganix or some other agency. They need these details to help them evaluate whether Loganix is the right choice for them.

Including all these details makes our narrative case studies the equivalent of a meal, for those who are hungry to learn everything.

We also created a snapshot case study for this same customer success story.

This format is significantly shorter, hitting the highlights without going into all the details. The solution section in particular is shorter.

To make the point, here’s a page from that section:

I’ve circled the same points as in the narrative version of this case study, but here they’re abbreviated, as you can see.

By reducing these points to a couple of lines, we’ve made this case study more digestible and scannable. It’s perfect for busy executives who just want the highlights or top-of-funnel leads who are still discovering their options.

If the narrative case study is a full sitdown meal, the snapshot is like a meal you can eat on the run—satisfying but quick.

We also created a slide deck for the same customer success story.

The slide deck tells the same story but hits the highest points only.

After all, the idea isn’t to have leads sit down and read the slides but for the sales team to present them and provide context verbally.

Here’s the slide where we boiled down the challenges that Rankings.io faced to three bullet points:

While this slide deck is brief and to the point, it still includes important social proof, such as quotes from the customer:

If we return to our food metaphor, the slide deck is equivalent to a snack—it gives leads a few mouthfuls to try.

If they like the taste—and want more—they can move on to the narrative or snapshot versions.

We created yet another asset for this customer success story: a HTML teaser page.

The HTML teaser is designed for Loganix’s website. It’s short enough for easy online scanning but long enough to communicate essential points.

Here’s the desktop version:

This snackable size is perfect for the web—and can again drive leads to the full story for those who want more details (note the “download the full story” call to action button at the top).

We also had the pleasure of creating some audiograms for Loganix for this story.

These audiograms consist of short audio snippets of Rankings.io’s President and Founder, Chris Dreyer, explaining how amazing Loganix is—in his own words!

These audio clips were taken directly from the interview we conducted for the case study.

Audiograms can generate interest in top-of-funnel leads while driving others to the narrative or snapshot versions for more info.

Another way for Loganix to cultivate leads with this success story is to share it on social media and in marketing campaigns.

That’s why we created image cards with testimonials that can be used in any number of ways:

Again, these little “nibbles” can be used to drive leads to longer versions of the customer success story.

Using design elements for greater versatility

We’ve talked about how different formats can be used for different points in your funnel, using Loganix’s customer success story as an example.

But we should also talk about how we use design elements to make these assets more versatile.

Sidebars, visuals, and highlighting help these assets do “double duty,” reaching audiences that they may not be exactly designed to reach.

For example, we include a sidebar of highlights in all our narrative case studies.

Here’s an example, again from Loganix (sidebar highlights circled in red):

While this narrative case study is long and detailed, this sidebar still makes it easy for busy executives or top-of-funnel leads to get the gist without reading the entire study.

It’s like embedding a snack within a sitdown meal!

This method of using design elements to increase versatility is so effective, we also use it in many of our snapshot case studies.

Here’s an example from Loganix (highlights circled in red):

Again, this side bar helps make even this shorter case study more scannable and versatile.

We use these design elements, and others, to make every asset we create more flexible and versatile.

Focus less on length and more on purpose

Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer to the question of how long your case study should be.

You have to think about the story you want to tell, whom you’re targeting and how you will use it.

If you want to get the most mileage from your case studies, best practice is to create a variety of assets to satisfy different appetites, from image cards (“nibbles”) to HTML teasers (“snacks”) to full written studies (“meals”).

At the same time, you can use design elements to make all of these assets more versatile.

So if you’re still asking yourself how long your case study should be, you may be asking the wrong question.

Instead, ask yourself how many ways you can tell the story.

Need help transforming your customer success stories into valuable marketing assets?

Contact us to start the conversation.

Head of Writing and Interviewing

Based in Vancouver, Canada, Holly is pumped to tell stories of companies succeeding and doing good in the world.

Ya, you like that? Well, there’s more where that came from!

Should you send case study interview questions in advance.

Sending your case study interview questions to your interviewee in advance sounds like a no-brainer, doesn’t it? And certainly, if you type “should you send case study interview questions in advance” into Google, that’s the boilerplate advice everyone gives. But is that truly good advice? Or does it depend on the situation? At Case Study Buddy, we’ve conducted (literally) hundreds and hundreds of case study interviews, and we’re continually testing new and better ways of conducting them. And the answer...

Best AI Case Study Examples in 2024 (And a How-To Guide!)

Who has the best case studies for AI solutions? B2B buyers’ heads are spinning with the opportunities that AI makes possible. But in a noisy, technical space where hundreds of new AI solutions and use cases are popping up overnight, many buyers don’t know how to navigate these opportunities—or who they can trust. Your customers are as skeptical as they are excited, thinking… “I’m confused by the complexity of your technology.” “I’m unsure whether there’s clear ROI.” “I’m concerned about...

How to Write Cybersecurity Case Studies

When it comes to case studies, cybersecurity poses special challenges. The cybersecurity landscape is saturated with solutions—and so sales and marketing teams have never been hungrier for customer success stories they can share as proof of their product’s abilities. But cybersecurity clients are very reluctant to be featured. They don’t want to talk about the time they almost got hacked, they don’t want to disclose the details of their setup and risk more attacks, and they just plain don’t want...

Let’s tell your stories together.

Get in touch to start a conversation.

🎉 Case Study Buddy has been acquired by Testimonial Hero 🎉 Learn more at testimonialhero.com

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is an in-depth examination of a single case or a few selected cases within a real-world context. Case study research is widely used across disciplines such as psychology, sociology, business, and education to explore complex phenomena in detail. Unlike other research methods that aim for broad generalizations, case studies offer an intensive understanding of a specific individual, group, event, or situation.

A case study is a research method that involves a detailed examination of a subject (the “case”) within its real-life context. Case studies are used to explore the causes of underlying principles, behaviors, or outcomes, providing insights into the nuances of the studied phenomena. This approach allows researchers to capture a wide array of factors and interactions that may not be visible in other methods, such as experiments or surveys.

Key Characteristics of Case Studies :

- Focus on a specific case, individual, or event.

- Provide in-depth analysis and contextual understanding.

- Useful for exploring new or complex phenomena.

- Generate rich qualitative data that contributes to theory building.

Types of Case Studies

Case studies can be classified into different types depending on their purpose and methodology. Common types include exploratory , descriptive , explanatory , intrinsic , and instrumental case studies.

1. Exploratory Case Study

Definition : An exploratory case study investigates an area where little is known. It helps to identify questions, variables, and hypotheses for future research.

Characteristics :

- Often used in the early stages of research.

- Focuses on discovery and hypothesis generation.

- Helps clarify research questions.

Example : Examining how remote work affects team dynamics in an organization that has recently transitioned to a work-from-home model.

2. Descriptive Case Study

Definition : A descriptive case study provides a detailed account of a particular case, describing it within its context. The goal is to provide a complete and accurate depiction without necessarily exploring underlying causes.

- Focuses on describing the case in detail.

- Provides comprehensive data to paint a clear picture of the phenomenon.

- Helps understand “what” happened without delving into “why.”

Example : Documenting the process and outcomes of a corporate restructuring within a company, describing the actions taken and their immediate effects.

3. Explanatory Case Study

Definition : An explanatory case study aims to explain the cause-and-effect relationships of a particular case. It focuses on understanding “how” or “why” something happened.

- Useful for causal analysis.

- Aims to provide insights into mechanisms and processes.

- Often used in social sciences and psychology to study behavior and interactions.

Example : Investigating why a school’s test scores improved significantly after implementing a new teaching method.

4. Intrinsic Case Study

Definition : An intrinsic case study focuses on a unique or interesting case, not because of what it represents but because of its intrinsic value. The researcher’s interest lies in understanding the case itself.

- Driven by the researcher’s interest in the particular case.

- Not meant to generalize findings to broader contexts.

- Focuses on gaining a deep understanding of the specific case.

Example : Studying a particularly successful start-up to understand its founder’s unique leadership style.

5. Instrumental Case Study

Definition : An instrumental case study examines a particular case to gain insights into a broader issue. The case serves as a tool for understanding something more general.

- The case itself is not the focus; rather, it is a vehicle for exploring broader principles or theories.

- Helps apply findings to similar situations or cases.

- Useful for theory testing or development.

Example : Studying a well-known patient’s therapy process to understand the general principles of effective psychological treatment.

Methods of Conducting a Case Study

Case studies can involve various research methods to collect data and analyze the case comprehensively. The primary methods include interviews , observations , document analysis , and surveys .

1. Interviews

Definition : Interviews allow researchers to gather in-depth information from individuals involved in the case. These interviews can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured, depending on the study’s goals.

- Develop a list of open-ended questions aligned with the study’s objectives.

- Conduct interviews with individuals directly or indirectly involved in the case.

- Record, transcribe, and analyze the responses to identify key themes.

Example : Interviewing employees, managers, and clients in a company to understand the effects of a new business strategy.

2. Observations

Definition : Observations involve watching and recording behaviors, actions, and events within the case’s natural setting. This method provides first-hand data on interactions, routines, and environmental factors.

- Define the behaviors and interactions to observe.

- Conduct observations systematically, noting relevant details.

- Analyze patterns and connections in the observed data.

Example : Observing interactions between teachers and students in a classroom to evaluate the effectiveness of a teaching method.

3. Document Analysis

Definition : Document analysis involves reviewing existing documents related to the case, such as reports, emails, memos, policies, or archival records. This provides historical and contextual data that can complement other data sources.

- Identify relevant documents that offer insights into the case.

- Systematically review and code the documents for themes or categories.

- Compare document findings with data from interviews and observations.

Example : Analyzing company policies, performance reports, and emails to study the process of implementing a new organizational structure.

Definition : Surveys are structured questionnaires administered to a group of people involved in the case. Surveys are especially useful for gathering quantitative data that supports or complements qualitative findings.

- Design survey questions that align with the research goals.

- Distribute the survey to a sample of participants.

- Analyze the survey responses, often using statistical methods.

Example : Conducting a survey among customers to measure satisfaction levels after a service redesign.

Case Study Guide: Step-by-Step Process

Step 1: define the research questions.

- Clearly outline what you aim to understand or explain.

- Define specific questions that the case study will answer, such as “What factors led to X outcome?”

Step 2: Select the Case(s)

- Choose a case (or cases) that are relevant to your research question.

- Ensure that the case is feasible to study, accessible, and likely to yield meaningful data.

Step 3: Determine the Data Collection Methods

- Decide which methods (e.g., interviews, observations, document analysis) will best capture the information needed.

- Consider combining multiple methods to gather rich, well-rounded data.

Step 4: Collect Data

- Gather data using your chosen methods, following ethical guidelines such as informed consent and confidentiality.

- Take comprehensive notes and record interviews or observations when possible.

Step 5: Analyze the Data

- Organize the data into themes, patterns, or categories.

- Use qualitative or quantitative analysis methods, depending on the nature of the data.

- Compare findings across data sources to identify consistencies and discrepancies.

Step 6: Interpret Findings

- Draw conclusions based on the analysis, relating the findings to your research questions.

- Consider alternative explanations and assess the generalizability of your findings.

Step 7: Report Results

- Write a detailed report that presents your findings and explains their implications.

- Discuss the limitations of the case study and potential directions for future research.

Examples of Case Study Applications

- Objective : To understand the success factors of a high-growth tech company.

- Methods : Interviews with key executives, analysis of internal reports, and customer satisfaction surveys.

- Outcome : Insights into unique management practices and customer engagement strategies.

- Objective : To examine the impact of project-based learning on student engagement.

- Methods : Observations in classrooms, interviews with teachers, and analysis of student performance data.

- Outcome : Evidence of increased engagement and enhanced critical thinking skills among students.

- Objective : To explore the effectiveness of a new mental health intervention.

- Methods : Interviews with patients, assessment of clinical outcomes, and reviews of therapist notes.

- Outcome : Identification of factors that contribute to successful treatment outcomes.

- Objective : To assess the impact of urban development on local wildlife.

- Methods : Observations of wildlife, analysis of environmental data, and interviews with residents.

- Outcome : Findings showing the effects of urban sprawl on species distribution and biodiversity.

Case studies are valuable for in-depth exploration and understanding of complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. By using methods such as interviews, observations, document analysis, and surveys, researchers can obtain comprehensive data and generate insights that are specific to the case. Whether exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory, case studies offer unique opportunities for understanding and discovering practical applications for theories.

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers . The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–559.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research . SAGE Publications.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Thomas, G. (2016). How to Do Your Case Study (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The case study approach

Sarah crowe, kathrin cresswell, ann robertson, anthony avery, aziz sheikh.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2010 Nov 29; Accepted 2011 Jun 27; Collection date 2011.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. Based on our experiences of conducting several health-related case studies, we reflect on the different types of case study design, the specific research questions this approach can help answer, the data sources that tend to be used, and the particular advantages and disadvantages of employing this methodological approach. The paper concludes with key pointers to aid those designing and appraising proposals for conducting case study research, and a checklist to help readers assess the quality of case study reports.

Introduction

The case study approach is particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context. Our aim in writing this piece is to provide insights into when to consider employing this approach and an overview of key methodological considerations in relation to the design, planning, analysis, interpretation and reporting of case studies.

The illustrative 'grand round', 'case report' and 'case series' have a long tradition in clinical practice and research. Presenting detailed critiques, typically of one or more patients, aims to provide insights into aspects of the clinical case and, in doing so, illustrate broader lessons that may be learnt. In research, the conceptually-related case study approach can be used, for example, to describe in detail a patient's episode of care, explore professional attitudes to and experiences of a new policy initiative or service development or more generally to 'investigate contemporary phenomena within its real-life context' [ 1 ]. Based on our experiences of conducting a range of case studies, we reflect on when to consider using this approach, discuss the key steps involved and illustrate, with examples, some of the practical challenges of attaining an in-depth understanding of a 'case' as an integrated whole. In keeping with previously published work, we acknowledge the importance of theory to underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies[ 2 ]. In so doing, we make passing reference to the different epistemological approaches used in case study research by key theoreticians and methodologists in this field of enquiry.

This paper is structured around the following main questions: What is a case study? What are case studies used for? How are case studies conducted? What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided? We draw in particular on four of our own recently published examples of case studies (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 and 4 ) and those of others to illustrate our discussion[ 3 - 7 ].

Example of a case study investigating the reasons for differences in recruitment rates of minority ethnic people in asthma research[ 3 ]

Example of a case study investigating the process of planning and implementing a service in Primary Care Organisations[ 4 ]

Example of a case study investigating the introduction of the electronic health records[ 5 ]

Example of a case study investigating the formal and informal ways students learn about patient safety[ 6 ]

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. A case study can be defined in a variety of ways (Table 5 ), the central tenet being the need to explore an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context. It is for this reason sometimes referred to as a "naturalistic" design; this is in contrast to an "experimental" design (such as a randomised controlled trial) in which the investigator seeks to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.

Definitions of a case study

Stake's work has been particularly influential in defining the case study approach to scientific enquiry. He has helpfully characterised three main types of case study: intrinsic , instrumental and collective [ 8 ]. An intrinsic case study is typically undertaken to learn about a unique phenomenon. The researcher should define the uniqueness of the phenomenon, which distinguishes it from all others. In contrast, the instrumental case study uses a particular case (some of which may be better than others) to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. The collective case study involves studying multiple cases simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a still broader appreciation of a particular issue.

These are however not necessarily mutually exclusive categories. In the first of our examples (Table 1 ), we undertook an intrinsic case study to investigate the issue of recruitment of minority ethnic people into the specific context of asthma research studies, but it developed into a instrumental case study through seeking to understand the issue of recruitment of these marginalised populations more generally, generating a number of the findings that are potentially transferable to other disease contexts[ 3 ]. In contrast, the other three examples (see Tables 2 , 3 and 4 ) employed collective case study designs to study the introduction of workforce reconfiguration in primary care, the implementation of electronic health records into hospitals, and to understand the ways in which healthcare students learn about patient safety considerations[ 4 - 6 ]. Although our study focusing on the introduction of General Practitioners with Specialist Interests (Table 2 ) was explicitly collective in design (four contrasting primary care organisations were studied), is was also instrumental in that this particular professional group was studied as an exemplar of the more general phenomenon of workforce redesign[ 4 ].

What are case studies used for?

According to Yin, case studies can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur[ 1 ]. These can, for example, help to understand and explain causal links and pathways resulting from a new policy initiative or service development (see Tables 2 and 3 , for example)[ 1 ]. In contrast to experimental designs, which seek to test a specific hypothesis through deliberately manipulating the environment (like, for example, in a randomised controlled trial giving a new drug to randomly selected individuals and then comparing outcomes with controls),[ 9 ] the case study approach lends itself well to capturing information on more explanatory ' how ', 'what' and ' why ' questions, such as ' how is the intervention being implemented and received on the ground?'. The case study approach can offer additional insights into what gaps exist in its delivery or why one implementation strategy might be chosen over another. This in turn can help develop or refine theory, as shown in our study of the teaching of patient safety in undergraduate curricula (Table 4 )[ 6 , 10 ]. Key questions to consider when selecting the most appropriate study design are whether it is desirable or indeed possible to undertake a formal experimental investigation in which individuals and/or organisations are allocated to an intervention or control arm? Or whether the wish is to obtain a more naturalistic understanding of an issue? The former is ideally studied using a controlled experimental design, whereas the latter is more appropriately studied using a case study design.

Case studies may be approached in different ways depending on the epistemological standpoint of the researcher, that is, whether they take a critical (questioning one's own and others' assumptions), interpretivist (trying to understand individual and shared social meanings) or positivist approach (orientating towards the criteria of natural sciences, such as focusing on generalisability considerations) (Table 6 ). Whilst such a schema can be conceptually helpful, it may be appropriate to draw on more than one approach in any case study, particularly in the context of conducting health services research. Doolin has, for example, noted that in the context of undertaking interpretative case studies, researchers can usefully draw on a critical, reflective perspective which seeks to take into account the wider social and political environment that has shaped the case[ 11 ].

Example of epistemological approaches that may be used in case study research

How are case studies conducted?

Here, we focus on the main stages of research activity when planning and undertaking a case study; the crucial stages are: defining the case; selecting the case(s); collecting and analysing the data; interpreting data; and reporting the findings.

Defining the case

Carefully formulated research question(s), informed by the existing literature and a prior appreciation of the theoretical issues and setting(s), are all important in appropriately and succinctly defining the case[ 8 , 12 ]. Crucially, each case should have a pre-defined boundary which clarifies the nature and time period covered by the case study (i.e. its scope, beginning and end), the relevant social group, organisation or geographical area of interest to the investigator, the types of evidence to be collected, and the priorities for data collection and analysis (see Table 7 )[ 1 ]. A theory driven approach to defining the case may help generate knowledge that is potentially transferable to a range of clinical contexts and behaviours; using theory is also likely to result in a more informed appreciation of, for example, how and why interventions have succeeded or failed[ 13 ].

Example of a checklist for rating a case study proposal[ 8 ]

For example, in our evaluation of the introduction of electronic health records in English hospitals (Table 3 ), we defined our cases as the NHS Trusts that were receiving the new technology[ 5 ]. Our focus was on how the technology was being implemented. However, if the primary research interest had been on the social and organisational dimensions of implementation, we might have defined our case differently as a grouping of healthcare professionals (e.g. doctors and/or nurses). The precise beginning and end of the case may however prove difficult to define. Pursuing this same example, when does the process of implementation and adoption of an electronic health record system really begin or end? Such judgements will inevitably be influenced by a range of factors, including the research question, theory of interest, the scope and richness of the gathered data and the resources available to the research team.

Selecting the case(s)

The decision on how to select the case(s) to study is a very important one that merits some reflection. In an intrinsic case study, the case is selected on its own merits[ 8 ]. The case is selected not because it is representative of other cases, but because of its uniqueness, which is of genuine interest to the researchers. This was, for example, the case in our study of the recruitment of minority ethnic participants into asthma research (Table 1 ) as our earlier work had demonstrated the marginalisation of minority ethnic people with asthma, despite evidence of disproportionate asthma morbidity[ 14 , 15 ]. In another example of an intrinsic case study, Hellstrom et al.[ 16 ] studied an elderly married couple living with dementia to explore how dementia had impacted on their understanding of home, their everyday life and their relationships.

For an instrumental case study, selecting a "typical" case can work well[ 8 ]. In contrast to the intrinsic case study, the particular case which is chosen is of less importance than selecting a case that allows the researcher to investigate an issue or phenomenon. For example, in order to gain an understanding of doctors' responses to health policy initiatives, Som undertook an instrumental case study interviewing clinicians who had a range of responsibilities for clinical governance in one NHS acute hospital trust[ 17 ]. Sampling a "deviant" or "atypical" case may however prove even more informative, potentially enabling the researcher to identify causal processes, generate hypotheses and develop theory.

In collective or multiple case studies, a number of cases are carefully selected. This offers the advantage of allowing comparisons to be made across several cases and/or replication. Choosing a "typical" case may enable the findings to be generalised to theory (i.e. analytical generalisation) or to test theory by replicating the findings in a second or even a third case (i.e. replication logic)[ 1 ]. Yin suggests two or three literal replications (i.e. predicting similar results) if the theory is straightforward and five or more if the theory is more subtle. However, critics might argue that selecting 'cases' in this way is insufficiently reflexive and ill-suited to the complexities of contemporary healthcare organisations.

The selected case study site(s) should allow the research team access to the group of individuals, the organisation, the processes or whatever else constitutes the chosen unit of analysis for the study. Access is therefore a central consideration; the researcher needs to come to know the case study site(s) well and to work cooperatively with them. Selected cases need to be not only interesting but also hospitable to the inquiry [ 8 ] if they are to be informative and answer the research question(s). Case study sites may also be pre-selected for the researcher, with decisions being influenced by key stakeholders. For example, our selection of case study sites in the evaluation of the implementation and adoption of electronic health record systems (see Table 3 ) was heavily influenced by NHS Connecting for Health, the government agency that was responsible for overseeing the National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT)[ 5 ]. This prominent stakeholder had already selected the NHS sites (through a competitive bidding process) to be early adopters of the electronic health record systems and had negotiated contracts that detailed the deployment timelines.

It is also important to consider in advance the likely burden and risks associated with participation for those who (or the site(s) which) comprise the case study. Of particular importance is the obligation for the researcher to think through the ethical implications of the study (e.g. the risk of inadvertently breaching anonymity or confidentiality) and to ensure that potential participants/participating sites are provided with sufficient information to make an informed choice about joining the study. The outcome of providing this information might be that the emotive burden associated with participation, or the organisational disruption associated with supporting the fieldwork, is considered so high that the individuals or sites decide against participation.

In our example of evaluating implementations of electronic health record systems, given the restricted number of early adopter sites available to us, we sought purposively to select a diverse range of implementation cases among those that were available[ 5 ]. We chose a mixture of teaching, non-teaching and Foundation Trust hospitals, and examples of each of the three electronic health record systems procured centrally by the NPfIT. At one recruited site, it quickly became apparent that access was problematic because of competing demands on that organisation. Recognising the importance of full access and co-operative working for generating rich data, the research team decided not to pursue work at that site and instead to focus on other recruited sites.

Collecting the data

In order to develop a thorough understanding of the case, the case study approach usually involves the collection of multiple sources of evidence, using a range of quantitative (e.g. questionnaires, audits and analysis of routinely collected healthcare data) and more commonly qualitative techniques (e.g. interviews, focus groups and observations). The use of multiple sources of data (data triangulation) has been advocated as a way of increasing the internal validity of a study (i.e. the extent to which the method is appropriate to answer the research question)[ 8 , 18 - 21 ]. An underlying assumption is that data collected in different ways should lead to similar conclusions, and approaching the same issue from different angles can help develop a holistic picture of the phenomenon (Table 2 )[ 4 ].

Brazier and colleagues used a mixed-methods case study approach to investigate the impact of a cancer care programme[ 22 ]. Here, quantitative measures were collected with questionnaires before, and five months after, the start of the intervention which did not yield any statistically significant results. Qualitative interviews with patients however helped provide an insight into potentially beneficial process-related aspects of the programme, such as greater, perceived patient involvement in care. The authors reported how this case study approach provided a number of contextual factors likely to influence the effectiveness of the intervention and which were not likely to have been obtained from quantitative methods alone.

In collective or multiple case studies, data collection needs to be flexible enough to allow a detailed description of each individual case to be developed (e.g. the nature of different cancer care programmes), before considering the emerging similarities and differences in cross-case comparisons (e.g. to explore why one programme is more effective than another). It is important that data sources from different cases are, where possible, broadly comparable for this purpose even though they may vary in nature and depth.

Analysing, interpreting and reporting case studies

Making sense and offering a coherent interpretation of the typically disparate sources of data (whether qualitative alone or together with quantitative) is far from straightforward. Repeated reviewing and sorting of the voluminous and detail-rich data are integral to the process of analysis. In collective case studies, it is helpful to analyse data relating to the individual component cases first, before making comparisons across cases. Attention needs to be paid to variations within each case and, where relevant, the relationship between different causes, effects and outcomes[ 23 ]. Data will need to be organised and coded to allow the key issues, both derived from the literature and emerging from the dataset, to be easily retrieved at a later stage. An initial coding frame can help capture these issues and can be applied systematically to the whole dataset with the aid of a qualitative data analysis software package.

The Framework approach is a practical approach, comprising of five stages (familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping and interpretation) , to managing and analysing large datasets particularly if time is limited, as was the case in our study of recruitment of South Asians into asthma research (Table 1 )[ 3 , 24 ]. Theoretical frameworks may also play an important role in integrating different sources of data and examining emerging themes. For example, we drew on a socio-technical framework to help explain the connections between different elements - technology; people; and the organisational settings within which they worked - in our study of the introduction of electronic health record systems (Table 3 )[ 5 ]. Our study of patient safety in undergraduate curricula drew on an evaluation-based approach to design and analysis, which emphasised the importance of the academic, organisational and practice contexts through which students learn (Table 4 )[ 6 ].

Case study findings can have implications both for theory development and theory testing. They may establish, strengthen or weaken historical explanations of a case and, in certain circumstances, allow theoretical (as opposed to statistical) generalisation beyond the particular cases studied[ 12 ]. These theoretical lenses should not, however, constitute a strait-jacket and the cases should not be "forced to fit" the particular theoretical framework that is being employed.

When reporting findings, it is important to provide the reader with enough contextual information to understand the processes that were followed and how the conclusions were reached. In a collective case study, researchers may choose to present the findings from individual cases separately before amalgamating across cases. Care must be taken to ensure the anonymity of both case sites and individual participants (if agreed in advance) by allocating appropriate codes or withholding descriptors. In the example given in Table 3 , we decided against providing detailed information on the NHS sites and individual participants in order to avoid the risk of inadvertent disclosure of identities[ 5 , 25 ].

What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided?

The case study approach is, as with all research, not without its limitations. When investigating the formal and informal ways undergraduate students learn about patient safety (Table 4 ), for example, we rapidly accumulated a large quantity of data. The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted on the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources. This highlights a more general point of the importance of avoiding the temptation to collect as much data as possible; adequate time also needs to be set aside for data analysis and interpretation of what are often highly complex datasets.

Case study research has sometimes been criticised for lacking scientific rigour and providing little basis for generalisation (i.e. producing findings that may be transferable to other settings)[ 1 ]. There are several ways to address these concerns, including: the use of theoretical sampling (i.e. drawing on a particular conceptual framework); respondent validation (i.e. participants checking emerging findings and the researcher's interpretation, and providing an opinion as to whether they feel these are accurate); and transparency throughout the research process (see Table 8 )[ 8 , 18 - 21 , 23 , 26 ]. Transparency can be achieved by describing in detail the steps involved in case selection, data collection, the reasons for the particular methods chosen, and the researcher's background and level of involvement (i.e. being explicit about how the researcher has influenced data collection and interpretation). Seeking potential, alternative explanations, and being explicit about how interpretations and conclusions were reached, help readers to judge the trustworthiness of the case study report. Stake provides a critique checklist for a case study report (Table 9 )[ 8 ].

Potential pitfalls and mitigating actions when undertaking case study research

Stake's checklist for assessing the quality of a case study report[ 8 ]

Conclusions

The case study approach allows, amongst other things, critical events, interventions, policy developments and programme-based service reforms to be studied in detail in a real-life context. It should therefore be considered when an experimental design is either inappropriate to answer the research questions posed or impossible to undertake. Considering the frequency with which implementations of innovations are now taking place in healthcare settings and how well the case study approach lends itself to in-depth, complex health service research, we believe this approach should be more widely considered by researchers. Though inherently challenging, the research case study can, if carefully conceptualised and thoughtfully undertaken and reported, yield powerful insights into many important aspects of health and healthcare delivery.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AS conceived this article. SC, KC and AR wrote this paper with GH, AA and AS all commenting on various drafts. SC and AS are guarantors.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/100/prepub

Contributor Information

Sarah Crowe, Email: [email protected].

Kathrin Cresswell, Email: [email protected].

Ann Robertson, Email: [email protected].

Guro Huby, Email: [email protected].

Anthony Avery, Email: [email protected].

Aziz Sheikh, Email: [email protected].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants and colleagues who contributed to the individual case studies that we have drawn on. This work received no direct funding, but it has been informed by projects funded by Asthma UK, the NHS Service Delivery Organisation, NHS Connecting for Health Evaluation Programme, and Patient Safety Research Portfolio. We would also like to thank the expert reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. Our thanks are also due to Dr. Allison Worth who commented on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

- Yin RK. Case study research, design and method. 4. London: Sage Publications Ltd.; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keen J, Packwood T. Qualitative research; case study evaluation. BMJ. 1995;311:444–446. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7002.444. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheikh A, Halani L, Bhopal R, Netuveli G, Partridge M, Car J. et al. Facilitating the Recruitment of Minority Ethnic People into Research: Qualitative Case Study of South Asians and Asthma. PLoS Med. 2009;6(10):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000148. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinnock H Huby G Powell A Kielmann T Price D Williams S et al. The process of planning, development and implementation of a General Practitioner with a Special Interest service in Primary Care Organisations in England and Wales: a comparative prospective case study Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO) 2008 http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/project/99-final-report.pdf 15318916

- Robertson A, Cresswell K, Takian A, Petrakaki D, Crowe S, Cornford T. et al. Prospective evaluation of the implementation and adoption of NHS Connecting for Health's national electronic health record in secondary care in England: interim findings. BMJ. 2010;41:c4564. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4564. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearson P, Steven A, Howe A, Sheikh A, Ashcroft D, Smith P. the Patient Safety Education Study Group. Learning about patient safety: organisational context and culture in the education of healthcare professionals. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010;15:4–10. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009052. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van Harten WH, Casparie TF, Fisscher OA. The evaluation of the introduction of a quality management system: a process-oriented case study in a large rehabilitation hospital. Health Policy. 2002;60(1):17–37. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00187-7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stake RE. The art of case study research. London: Sage Publications Ltd.; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheikh A, Smeeth L, Ashcroft R. Randomised controlled trials in primary care: scope and application. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(482):746–51. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King G, Keohane R, Verba S. Designing Social Inquiry. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doolin B. Information technology as disciplinary technology: being critical in interpretative research on information systems. Journal of Information Technology. 1998;13:301–311. doi: 10.1057/jit.1998.8. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- George AL, Bennett A. Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eccles M. the Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG) Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implementation Science. 2006;1:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Netuveli G, Hurwitz B, Levy M, Fletcher M, Barnes G, Durham SR, Sheikh A. Ethnic variations in UK asthma frequency, morbidity, and health-service use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):312–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17785-X. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheikh A, Panesar SS, Lasserson T, Netuveli G. Recruitment of ethnic minorities to asthma studies. Thorax. 2004;59(7):634. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U. 'We do things together': A case study of 'couplehood' in dementia. Dementia. 2005;4:7–22. doi: 10.1177/1471301205049188. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Som CV. Nothing seems to have changed, nothing seems to be changing and perhaps nothing will change in the NHS: doctors' response to clinical governance. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2005;18:463–477. doi: 10.1108/09513550510608903. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001;322:1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320:50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mason J. Qualitative researching. London: Sage; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brazier A, Cooke K, Moravan V. Using Mixed Methods for Evaluating an Integrative Approach to Cancer Care: A Case Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7:5–17. doi: 10.1177/1534735407313395. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2. CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. Qualitative research in health care. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cresswell KM, Worth A, Sheikh A. Actor-Network Theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2010;10(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-67. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yin R. Case study research: design and methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yin R. Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1209–1224. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 2. Los Angeles: Sage; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howcroft D, Trauth E. Handbook of Critical Information Systems Research, Theory and Application. Cheltenham, UK: Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blakie N. Approaches to Social Enquiry. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doolin B. Power and resistance in the implementation of a medical management information system. Info Systems J. 2004;14:343–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2575.2004.00176.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bloomfield BP, Best A. Management consultants: systems development, power and the translation of problems. Sociological Review. 1992;40:533–560. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shanks G, Parr A. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems. Naples; 2003. Positivist, single case study research in information systems: A critical analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (249.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

👀 Turn any prompt into captivating visuals in seconds with our AI-powered design generator ✨ Try Piktochart AI!

How to Write a Case Study

You’re not the first person to feel like you’re drowning in data and information while planning for a case study. The good news is that it’s not as complex as you think.

This guide on how to write a case study breaks down the process into easy-to-follow steps — from information-gathering to writing to design. Pro tip : Get your free Piktochart account before you scroll down. This way, you can immediately put our tips to practice as you read along. Alternatively, you can hop over to our AI case study generator and find more examples of professional case study templates.

Why case studies matter across industries

A case study is not just a school assignment or an item on your marketing checklist. They are persuasive stories that demonstrate your expertise and build credibility. A well-crafted business case study can sway potential clients, as demonstrated by HubSpot’s study on the Lean Discovery Group , which helped increase deal value fivefold. Even in the social sciences, case studies like the “ Bobo doll experiment ” yield powerful insights, such as revealing the impact of media violence on children. It’s clear that case studies remain highly effective. Content Marketing Institute’s 2025 outlook even ranks them second only to video in terms of content effectiveness.

For these reasons, investing time and resources in crafting a unique and insightful case study that resonates with your target readers makes sense. This brings us to the next section!

Preparing your case study

Before you start writing your first case study, remember that a compelling case study requires careful preparation and research as your foundation for success..

1. Choose the right subject

Pick a case study subject that resonates with your target audience. A SaaS company aiming for enterprise clients, for example, might showcase a large corporation that saw major efficiency gains after using their software. Don’t forget to get consent before featuring any story.

2. Define your case study’s purpose

Purpose matters too. Joanna Knight, founding director at merl and developer of impact case studies for the Humanitarian Innovation Fund (HIF), explains , “Although many case studies have more than one purpose (e.g. for learning and communication), to maximize their effectiveness it is important to be clear about what we want to achieve with the case study.”

3. Gather information

Gathering relevant information might involve interviews, data analysis, and understanding the “why” behind the numbers.

A business case study might examine business proposals , financial reports, customer interviews, and marketing materials. On the other hand, academic case studies may pore over archival records, interviews, written observations, and artifacts. Recommended resource : How to Transcribe an Interview Quickly with Tips and Tool Hacks

4. Decide on the format

While the traditional lengthy case study can be effective, don’t be afraid to think outside the box. Consider your goals and audience – how can you best capture their attention and deliver your message?

Here are case study format alternatives you can try aside from the overly long ones:

- Interactive web pages

- Infographics

- Podcast episode

- Short blog post

Outside of a long-form text-based written case study, you can repurpose the content in several formats to share across your business’s distribution channels. You can combine visuals, interviews, and various elements for high-impact content.

You’ll find examples of these case study formats as you scroll down below.

5. Create an outline and structure

A clear structure ensures your case study narrative flows logically and effectively communicates your key message. The following frameworks are good starting points when planning for your case study’s structure:

The Problem-Hypothesis-Solution-Impact framework

The Problem-Hypothesis-Solution-Impact framework guides case studies with a clear narrative flow: define the problem, propose a hypothesis, outline the solution, and analyze the impact. For example, Jon Knuston, Head of Core IT Services at Rockwell Automation, used Gartner’s insights to accelerate digital transformation and achieved results within 90 days of starting his role (as detailed in this Gartner case study ). This structure is adaptable to your needs. Feel free to:

- Expand where needed: If your solution involves a complex process, dedicate more space to explaining each step.

- Highlight unique elements: Showcase unexpected innovations or surprising outcomes.

The MEAL framework

Incorporating frameworks relevant to your industry adds depth and credibility to your case study. The MEAL (Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning) framework is a good example.

This framework is commonly used by NGOs (non-government organizations) to assess the effectiveness of their projects. It provides a structured approach to:

- Monitoring: Tracking progress towards project goals.

- Evaluation: Assessing the impact and effectiveness of interventions.

- Accountability: Ensuring transparency and responsibility in project implementation.

- Learning: Using data and insights to improve future projects and strategies.

Read about the MEAL framework’s role in writing effective case studies .

Other case study frameworks worth exploring are:

- SWOT analysis : This model examines strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to the case study subject.

- Porter’s Five Forces analysis : This framework helps analyze competition in a case study. It looks at rivalry, new competitors, supplier and buyer power, and substitutes to understand how profitable an industry is.

- Customer journey map : For this framework, you’ll illustrate the customer’s experience with the product or service.

With your groundwork laid, it’s time to bring your case study to life and start writing!

Writing your case study

You’re halfway done! Keep these best practices in mind when writing your case study:

1. Use your chosen framework as a guide when writing

The framework you’ve picked during the preparation phase creates a logical flow. Make sure each section builds the story and supports your main point.

2. Be mindful of your headlines

Use clear, concise headlines that allow readers to skim and easily find the information they need. Intriguing headlines can also pique their curiosity and encourage them to read further.

Instead of a bland headline like “Project Overview,” try something more specific and engaging like “How We Increased Website Traffic by 40% in 3 Months.” This immediately tells the reader about the case study and highlights a key achievement.

3. Have a consistent narrative

Maintain a consistent tone and style throughout your case study. Whether you choose a formal or informal approach, make sure it aligns with your brand guidelines.

A brand style guide can be incredibly helpful for this. It provides clear guidelines for voice, tone, and visual elements to ensure every part of your case study feels cohesive. This consistency reinforces your brand identity and makes the information easier to digest. Need help with your brand style guide? We’ve got 11 amazing brand style guideline examples and ideas you can copy .

4. Include data to support claims

Back up your claims with real results, including both quantitative data and customer quotes.

For instance, don’t just write that your new marketing campaign was successful. Instead, include specific numbers like “The campaign generated a 15% increase in leads, a 10% rise in website traffic, and a 5% boost in sales.” Follow this up with a quote from a satisfied customer praising the campaign’s creativity and effectiveness. This combination of data and customer feedback paints a convincing picture of your success.

5. Show, don’t tell with visuals

Incorporate infographics, charts, and other visuals to make your case study more engaging, memorable, and persuasive.

Let’s say you’re writing a case study about a website redesign. Instead of just describing the changes, include:

- Before and after screenshots to visually demonstrate the improved user interface and design elements.

- Charts or graphs to show how the bounce rate decreased and conversion rates increased after the redesign.

- An infographic to summarize key results, such as improved page load speed and mobile responsiveness.

6. Focus on value, not on sales

While the ultimate goal might be to promote your product or service, avoid overt selling. Instead, focus on demonstrating your value by showcasing the customer’s success story.

7. Wrap it up with a memorable conclusion

A memorable conclusion is just as important as a strong introduction. It’s your last chance to leave a lasting impression on the reader and reinforce the key takeaways of your case study.

Here’s how to make it count:

- Summarize the key takeaways of your case study.

- Use a powerful quote or anecdote highlighting your solution’s positive impact.

- End with a call to action . Encourage readers to learn more about your company or product, download a resource, or contact you for a consultation.

Want to see these case study writing best practices come to life? Check out the case study examples below. In the next section, let’s explore how thoughtful design can transform your content into a visually compelling and persuasive experience.

Designing your case study

A well-designed case study is more than just words on a page. You can also use visuals to get attention in seconds and communicate your information quickly.

The good news is you don’t have to design your case studies from scratch if you use Piktochart templates . These professionally-designed templates provide a solid framework you can use for visually engaging content.

Here’s how to use Piktochart for case studies in 3 easy steps:

Step 1: Start with a template

Pick a template that aligns with your industry, brand, and the overall tone of your case study.

Step 2: Customize your design

Adapt the template to fit your specific content and style. Change the colors, fonts, and layout to match your brand identity.

Step 3: Add the final touches

Whether you use a template or start from scratch, these best practices will help you create a case study that looks as good as it reads:

High-quality visuals

Incorporate images, icons, and illustrations to break up the text and enhance your case study’s visual appeal. Use high-quality images that are relevant to your content and visually appealing.

Data visualization

Use data visualization to highlight key findings and trends in your case study. Piktochart offers a range of charts and graphs to present data in a clear and compelling way.

Visual hierarchy

Use headings, subheadings, and visual cues to guide the reader’s eye and emphasize key information. This creates a clear and consistent visual hierarchy to make your case study easy to read and understand.

Color palette

Pick a color palette that reflects your brand and complements the overall design of your case study. Use color consistently throughout your case study to create a cohesive look and feel.

White space

Don’t overcrowd the page. Use white space effectively to improve readability and create a more modern look.

Opt for fonts that are easy to read and visually appealing. Stick to two or three fonts to avoid visual clutter.

Proofreading

Typos and grammatical errors can undermine your case study’s credibility. Proofread your case study carefully before publishing it.

Recommended resources when designing your case study:

- Fonts and Colors for the Retail, Healthcare, and Financial Industries

- 4 Things You Need to Know to Pair Fonts Well

Get your free Piktochart account and start designing your case study. Now that you’ve got the case study design basics down, let’s see these principles in action with some inspiring case study examples below.

Real-word case study examples to learn from

Need inspiration for your next case study? Here’s how others are doing (and nailing!) it!

1. How to reduce your SLA by 99.9% (Breadcrumbs)

Breadcrumbs, an AI-powered lead scoring platform, excels at demonstrating the value of its product in this case study for Thinkific. Here’s why it works:

- Impactful storytelling: The case study uses a clear problem-solution-impact format and backs it up with compelling data (like a 99% SLA reduction) to show the power of lead scoring.