An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Third Gender in a Third World Country: Major Concerns and the “AIIMS Initiative”

Vivek dixit, bhavuk garg, nishank mehta, harleen kaur, rajesh malhotra.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2022 Dec 30.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

With a population dividend of around 1.3 billion, India is the largest democracy in the world that encompasses “unity in diversity”. The kaleidoscope of the socio-cultural fabric comprises the transgender population too, which has a historical context dating back millennia and also plays a vital role as described in Hindu scriptures. The Indian transgender person‘s community shows a variety of gender identities and sexual orientations, which is unlikely from the West, forming a culturally unique gender group. In India, transgender persons were recognised as the ‘third gender’ in 2014. The third gender population of India is marginalised to a great extent in every sector. Often, transgender persons have been the subjects of sociology, psychology, and health issues. There was a dearth of data regarding their major health problems including bone health, which has not been reported in India and elsewhere before this study. Through a prospective cross-sectional study design, we aimed to determine the current health status of transgender persons with a special emphasis on bone health. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis. The preliminary results of the study show poor bone health in the transgender population of India. The majority of transgender persons have low bone mineral density (BMD) at a much young age, even before the achievement of their peak bone mass. The health status of the transgender population in India is poor overall. Transgender persons have many impediments to optimal healthcare that requires holistic care. This study presents the current health challenges of the transgender population with a special emphasis on their bone health status as ‘AIIMS initiative’. This study also shows transgender persons human rights needs to be explicitly discussed. The stakeholders of social policies require an urgent attention to unfold the major concerns encompassing transgender persons.

Keywords: Transgender persons, Socioeconomic and significant health issues, Bone health, AIIMS initiative

Introduction

The existence of the third gender has been a part of Hindu Vedic literature for aeons (Kalra et al., 2016 ; Singh & Kumar, 2020 ). The transgender population is heterogeneous and thus forms a unique gender group with diverse gender identities. Research studies indicate that transgender persons are one of the most vulnerable populations in the world and therefore, India is no longer an exception (Chakrapani et al., 2021 ). Despite all-round of support and social recognition, the fundamental rights of transgender persons are yet to be protected in India and elsewhere (Ayoub, 2016 ; Kollman & Waites, 2009 ; Susan & Indira, 2022 ). In India, the attitude toward this populationis still prosecutorial. This population is exposed to ridicule, harassment, and bullying from a very young age. As per Indian law, Section 377 and the Transgender Person’s Bill in 2019 advocates to give equal rights and protection against discrimination, for human rights (Arvind et al., 2021 ; Chakrapani et al., 2021 ; Khatun, 2018 ).

While the transgender population is deeply entrenched in India, the mainstream population is surprisingly less aware of the transgender community and their health status (Srinivasan & Chandrasekaran, 2020 ). Before the 2011 census, there was no population record of transgender people in India. Still, the total population of transgender people was estimated at around 0.49 million (Census of India, 2011 ). In India, the transgender population is a marginalised group of society and has created their own way of developing their community. As per the national census data, this community has low literacy levels. Around 43% of transgender people are literate, compared to the 74% literacy rate in the general population (Saraswathi & Praveen, 2015 ). This group also faces many social, cultural, legal, and economic hurdles and are targeted for violence and harassment (Boyce, 2012 ; Saraswathi & Praveen, 2015 ). Poverty and economic exclusion have led to livelihood deprivation and prevented access to healthcare facilities. Adding to these, gender discrimination in the community, particularly at the hospitals, is bringing their morale down. Because of this, about 20% of the transgender community has specific healthcare needs that are not being met (Chettair, 2015 ; Khan, 2009 ).

The "trans" health

Transgender people experience health disparities and barriers to good healthcare services in India and worldwide. (Koken et al., 2009 ). They lack proper healthcare facilities due to social intolerance and stigmatisation. Being socially reticent has led to a widening gap between the transgender community and the conventional healthcare system; however, a lot is yet to be done in India to improve the healthcare accessibility of transgender community’s. Undoubtedly, due to media attention there is increased awareness of transgender person issues, but the lives of many transgender persons are still filled with hardships.

The suicide rate in India for the transgender population is a staggering 31%. About half of these have attempted suicide before the age of 20 (Virupaksha et al., 2016 ). 46.3% of transgender people have a lifetime presence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and 28.73% reported themselves to be currently engaging in NSSI (Saraswathi & Praveen, 2015 ). This group faces family rejection, unemployment, mental abuse, workplace discrimination. Due to fear of parental rejection, transgender people, leave their homes, which increases the risk of being alone and living their lives in poverty (Pisani et al., 2004 ).

Transgender persons are more at risk of HIV, which is found to be 49 times more prevalent in them than in the general population (Pisani et al., 2004 ). There are two evident barriers to accessing the treatment of HIV, which are stigma and transphobia. There are at least three factors responsible for transgender persons engaging in sex work, including social exclusion, economic vulnerability, and a lack of employment opportunities. Re-use of needles and unprotected intercourses are the main reasons for the high prevalence of HIV (Hatzenbuehler, 2008 ). For HIV prevalence, data substantiates that 27% of transgender persons are engaged in sex work, and 15% of people are not involved in the same. It is seen that HIV prevalence is nine times higher among transgender sex workers when compared to non-transgender female sex workers (Chettiar, 2015 ; Somasundaram, 2009 ; Virupaksha et al., 2016 ). Pisani et al. ( 2004 ) describe the selected infectious diseases that affect men who have sex with men (MSM) unevenly. Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) are most likely to develop in sexual minorities, further leading to emotional disorders later in their life (Hatzenbuehler, 2008 ).

According to research, 48% of transgender persons suffered from psychiatric disorders, but none received psychiatric consultation for these issues (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008 ; Somasundaram, 2009 ). Tobacco and alcohol consumption is higher in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals than in heterosexual individuals (Yeung et al., 2019 ). Higher rates of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infection have been found in gay individuals, When combined with tobacco use, resulted as higher risk of anal and other cancers (Pisani et al., 2004 ). Transgender persons often hide their illness from society and thus attempt self treatment. Due to a lack of awareness and education, most transgender people prefer to receive treatment from unprofessional quacks. These quacks even perform surgeries including removing genitalia which puts their lives at risk. (Singh et al., 2014 ). A study from southern part shows that certain risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are more common in transgender people than in the general population in, (Madhavan et al., 2020 ).

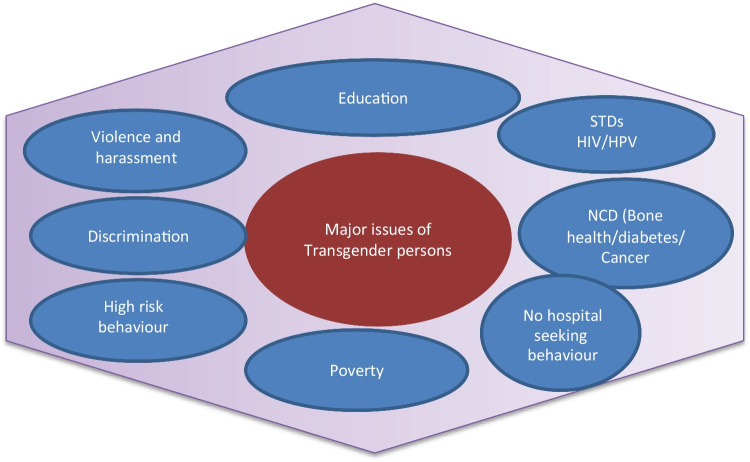

Other than STDs, several health issues involve bone health (see Fig. 1 ) (Unger, 2016 ). Metabolic bone diseases are often silent until they are forcefully revealed by a fracture. Gonadal sex steroids play a vital role in bone health (Davidge-Pitts & Clarke, 2019 ). In order to change gender, transgender persons often take unregulated amounts of hormonal therapy as a part of self-treatment, which impact their bone health negatively. A study shows that skeletal changes among adolescents and adults are a result of medical and surgical therapies for gender dysphoria (Cartya & Lopez, 2018 ; Rothman & Iwamoto, 2019 ; Stevenson & Tangpricha, 2019 ). Therefore, amidst the lack of basic healthcare facilities and awareness, transgender people in India often prefer self-treatment and mostly follow their group leader’s advice. High-risk behaviour and self-chance therapies in unregulated amounts led to secondary osteoporosis and osteopenia at an early stage of their life than rest of population.

Major Social and health issues of transgender persons (TG)

Transgender people’s health in the COVID Era

Transgender persons’ high-risk behaviour and ghettoization in India make them more susceptible to infections, including on-going COVID-19. Amidst COVID-19, an outbreak of the disease in their ghettos has seldom been reported. It may be that transgender persons often hide their illnesses. To the best of knowledge no reports about COVID-19 infection or hospitalisation have been noticed during the pandemic. However, the Health Ministry intensively observed this group during the COVID-19. As a part of their care, the Government of India has offered the transgender population considerable financial support during COVID time. Efforts are also being made to create awareness among them to adopt COVID-appropriate behaviours and also to ensure their vaccination. A good step has been taken by the Kerala State to start the "Integrity Clinic," which was the first multidisciplinary clinic for transgender health’ in India (Sukumar et al., 2020 ).

Methodology

This was a prospective cross-sectional study conducted between October 2018 and September 2021 in the department of orthopaedics at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute Ethics Committee (IEC) prior to the study. Financial support was received from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi. The Study was carried out by the department of Orthopedics, the All India Institute of Medical Science, New Delhi (AIIMS). Transgender persons were approached from their ghettos in Delhi and national capital regions after mapping of the habitats. A trained team healthworkers including a Scientist, female social worker, field worker and nursing staff interacted with group leaders of transgender community and concerned NGO’s. Through a health camp cum community interaction, transgender persons were given a presentation about the importance of bone health in life and common health issues in transgender population. A brief about the study was also described for their understanding. Transgender persons were recruited after obtaining their written consent. 10 ml of fasting blood sample was drawn for the routine biochemical investigations and selected hormonal assessment. Blood samples were carefully transported from the site to hospital. Samples were processed and serum samples were stored in -20 refrigerator. Transgender persons were abreast about their blood investigations and were also requested to get their BMD assessment at AIIMS institute. The parts of the data set were BMD (spine and hip region) through dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA scan) and parameters of bone mineral homeostasis, such as vitamin D, calcium, phosphorous, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).All reports were discussed with experts and advised the standard treatment whenever required. All records were entered in a dedicated computer and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

The findings of this study will help us compare the BMD data of the third gender with the existing data of the rest of the population. This initiative will also be helpful to draw attention towards the unmet needs for social justice and healthcare for the transgender population of India.

Objective, Research Question, and Hypothesis

Since the status of bone health in the transgender population has not been known, we aim to evaluate bone health among the transgender population of India. We hypothesised a low bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender population of India. The objective of this study was not only to determine the bone health status of the transgender population of India but also to study the common health issues among this population as well. Additionally, this initiative will be of help to create awareness among the stakeholders, including the transgender population.

Preliminary Findings

Descriptive statistics were used—mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency, and percentage. The mean age, BMI, vitamin D, calcium, phosphorous, and ALP were 25.5 ± 6.5 years, 21.8 ± 4.1 kg/m 2 , 13.38 + 7.9 ng/ml, 9.86 ± 0.86 mg/dl, 3.93 ± 2.17 mg/dl, and 186.4 ± 125.3 U/l, respectively. The major finding of the study was that out of 172 recruited subjects, 84.3% had vitamin D insufficiency (< 20 ng/ml) (Table 1 ). Importantly, a, past history of fracture was noted in 35 transgender persons (20%).

Preliminary findings of the study

The BMD was estimated in only 75 subjects, as the majority of transgender subjects did not opt to visit the hospital for BMD evaluation. The mean T scores in the spine and hip regions were − 1.5 ± 0.9 and − 0.72 ± 0.9 respectively. In the spine region, 50 subjects had a T score < − 1.5 (osteopenia range), while 10 subjects had one in the hip region (Table 1 ). Keeping in view the alarming bone health status of the transgender population, further comprehensive analysis, including hormonal, glycaemic, nutritional, and mental health findings, is under study, which would shed more light on the overall health status of the transgender population in totality.

This paper provides the current health challenges of the transgender population with a special emphasis on their bone health status as ‘AIIMS initiative’ on the path of social justice. The preliminary data is suggestive that our hypothesis is accepted that transgender persons have a low bone mineral density. Additionally, it could be inferred that after sex reassignment surgery (SRS), the mineral levels and hormonal levels got disrupted. Transgender persons need a comprehensive population health policy to enforce their constitutional rights in India. Similar efforts like the ‘AIIMS initiative’ are required from other centres to extend their services for transgender healthcare. It is predicted that this study will be the benchmark for the health governance of transgender persons. This study can be seen as a healthcare delivery model for transgender people. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first initiative taken for recording and analysing the health status of transgender people with a special focus on their bone health by any Indian association. BMD was assessed in only 75 subjects, which was the only limitation of the study. This study encourages health care workers to be accountable for such groups and provide the utmost help. Much needs to be done to bring the transgender population to the level of well-being that meets the Millennium Development Goal of “Health for All.” Leveraging the insights gained when recording data and the health status of the transgender population, the steps discussed throughout the script are required to provide the health equity for transgender persons. Nonetheless, such initiatives are required for transgender human rights and social work.

The majority of the transgender population of India has poor bone health status. A lot is yet to be done to restore the overall health of the transgender population on the path of human rights, social justice, and empowerment of the transgender population of India.

Prayer: The “third gender” in a third-world country shouldn ‘t be treated as “third class!”.

ICMR, New Delhi, India.

Data Availability

Declarations, conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Patient and public involvement.

Done as per standard methods.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained. We have reported whether we plan to disseminate the results to study participants and or patient organisations OR stated that dissemination to these groups is not possible/applicable.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vivek Dixit, Email: [email protected].

Harleen Kaur, Email: [email protected].

- Arvind, A., Pandya, A., Amin, L., Aggarwal, M., Agrawal, D., Tiwari, K., Singh, S., Nemkul, M., & Agarwal, P. (2021). Social strain, distress, and gender dysphoria among transgender women and Hijra in Vadodara, India. International Journal of Transgender Health, 22 (1–2), 1–15. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1845273 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Ayoub, P. (2016). When states come out: Europe’s sexual minorities and the politics of visibility . Cambridge University Press . 10.1017/CBO9781316336045

- Boyce P. Desirable rights: Same-sex sexual subjectivities, socio-economic transformations, global flows and boundaries–In India and beyond. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2014;16(10):1201–1215. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.944936. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cartaya J, Lopez X. Gender dysphoria in youth: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and Obesity. 2018;25(1):44–48. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000378. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Census of India. (2011). Retrieved from: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdata2011.html

- Chakrapani V, Scheim AI, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Rawat S, Baruah D, Bhatter A, Nelson R, Jaya A, Kaur M. Affirming and negotiating gender in family and social spaces: Stigma, mental health and resilience among transmasculine people in India. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2021;23:1–17. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2021.1901991. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chettiar A. Problems faced by Hijras (male to female transgenders) in Mumbai with reference to their health and harassment by the police. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity. 2015;5(9):752. doi: 10.7763/IJSSH.2015.V5.551. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davidge-Pitts C, Clarke BL. Transgender bone health. Maturitas. 2019;127:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.05.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dutta, A. (2014). Contradictory tendencies: The Supreme Court’s NALSA judgment on transgender recognition and rights. Journal of Indian Law and Society, 5 (Monsoon), 225.

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(12):1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalra B, Baruah MP, Kalra S. The Mahabharata and reproductive endocrinology. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;20(3):404. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.180004. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khan, S. I., Hussain, M. I., Parveen, S., Bhuiyan, M. I., Gourab, G., Sarker, G. F., & Sikder, J. (2009). Living on the extreme margin: Social exclusion of the transgender population (hijra) in Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition , 27 (4), 441. 10.3329/jhpn.v27i4.3388 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Khatun, H. (2018). LGBT movement in India. Social trends. Journal of the Department of Sociology of North Bengal University, 5 (31), 217–224. Accessed at: https://ir.nbu.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/3542/1/Vol.%205%20March%202018_11.pdf

- Koken JA, Bimbi DS, Parsons JT. Experiences of familial acceptance–rejection among transwomen of color. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(6):853. doi: 10.1037/a0017198. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kollman K, Waites M. The global politics of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender human rights: An introduction. Contemporary Politics. 2009;15(1):1–37. doi: 10.1080/13569770802674188. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Madhavan M, Reddy MM, Chinnakali P, Kar SS, Lakshminarayanan S. High levels of non-communicable diseases risk factors among transgenders in Puducherry, South India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2020;9(3):1538. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1128_19. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pisani E, Girault P, Gultom M, Sukartini N, Kumalawati J, Jazan S, Donegan E. HIV, syphilis infection, and sexual practices among transgenders, male sex workers, and other men who have sex with men in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(6):536–540. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007500. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothman MS, Iwamoto SJ. Bone health in the transgender population. Clinical Reviews in Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2019;17(2):77–85. doi: 10.1007/s12018-019-09261-3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saraswathi, A., & Praveen Prakash, A. (2015). To analyze the problems of transgender in India/study using new triangular combined Block Fuzzy Cognitive maps. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering , 6 (3), 186–195. 10.12732/ijpam

- Singh H, Kumar P. Hijra: An understanding. Journal of Psychosocial Research. 2020;15(1):79–89. doi: 10.32381/JPR.2020.15.01.6. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh Y, Aher A, Shaikh S, Mehta S, Robertson J, Chakrapani V. Gender transition services for Hijras and other male-to-female transgender people in India: Availability and barriers to access and use. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2014;15(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2014.890559. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Somasundaram O. Transgenderism: Facts and fictions. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;51(1):73. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.44917. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Srinivasan SP, Chandrasekaran S. Transsexualism in Hindu mythology. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2020;24(3):235. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_152_20. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevenson MO, Tangpricha V. Osteoporosis and bone health in transgender persons. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics. 2019;48(2):421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2019.02.006. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sukumar S, Ullatil V, Asokan A. Transgender health care status in Kerala. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2020;24(3):286. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_146_20. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Susan, D. N., & Indira, R. (2022). Transgender rights are human rights: A cross-national comparison of transgender rights in 204 countries. Journal of Human Rights . 21(5), 525–541. 10.1080/14754835.2022.2100985

- Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Translational Andrology and Urology. 2016;5(6):877. doi: 10.21037/tau.2016.09.04. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Virupaksha HG, Muralidhar D, Ramakrishna J. Suicide and suicidal behavior among transgender persons. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2016;38(6):505–509. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.194908. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, Ginsberg BA, Katz KA. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: Epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019;80(3):591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.045. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

- View on publisher site

- PDF (768.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Impact of legal recognition on the lives of the third gender: A study in Khulna district of Bangladesh

Shahinur akter, shankha saha.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author. [email protected]

Received 2023 Jun 13; Revised 2024 Mar 19; Accepted 2024 Mar 21; Collection date 2024 Apr 15.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

The third gender, popularly known as ‘ hijra’ , is a gender non-conforming person residing in Bangladesh. The government of Bangladesh granted legal recognition (LR) in 2013 to acknowledge them as a third gender. Thus, using an exploratory qualitative inquiry, the study sought to understand how LR affected the lives of the third gender community in the Khulna district of Bangladesh. Thirteen participants were selected following snowball sampling, and data were collected using in-depth interviews and key informant interviews. In the domain of socio-cultural dynamics, we found that the LR had enhanced the social participation of the third gender community and given them a sense of identity. On the contrary, within the domain of economic lives, the LR has not been able to change their economic situation. Moreover, in the third domain, we observed an improved situation for the third gender population in their right to vote and political participation, but in accessing healthcare facilities, inheritance, and legal services, LR remained unsatisfactory. The study recommends promoting acceptance and reducing social stigma towards the third gender community through awareness campaigns, providing professional training programs to enable their financial independence, and enacting laws to protect their rights in Bangladesh.

Keywords: Hijra , Third gender, Legal recognition, Bangladesh

1. Introduction

Hijra is a group of gender non-conforming people who do not identify with the ascribed binary gender categories (i.e., male and female) in South Asia [ 1 , 2 ]. In Bangladesh, traditionally, a hijra is considered a person who is born with defective or missing genitals, and is neither men or women [ 3 ]. However, some men become hijra through the process of castration who are viewed as sexually impotent and incapable of procreation [ 2 ]. Hijra has traditionally been translated as ‘eunuch’ in English, which refers to castrated males, or ‘hermaphrodite’, which refers to those with chromosome disorder, where the main issue is an abnormality of the male genitalia [ 4 ]. On the contrary, the term ‘transgender’ is widely used to refer to those who challenge binary gender conceptions and culturally dominant stereotyped roles and frequently live in the opposite gender role to their biological sex, either full-time or part-time [ 5 ]. There is a sharp distinction between hijra and transgender, the former is defined as people with sexual disability by birth, who because of bodily or genetic reasons cannot be categorized as male or female whereas the latter is defined as an individual who lives as a gender that differs to their assigned sex at birth.

The hijra community in Bangladesh is one of Asia's most disadvantaged and underprivileged populations, with minimal rights [ [6] , [7] , [8] , [9] , [10] ]. However, Bangladesh officially acknowledged the hijra as a third gender in 2013, making them eligible for low-paying jobs and priority education [ 11 , 12 ]. On all official documents, including passports and national identification cards (NIDs), those who identify as gender non-confirming can now choose to identify as a third gender rather than as male or female [ 3 ]. Even though they are officially acknowledged as third gender, the term hijra is often used in Bangladeshi society to denote individuals who do not identify as gender binary.

The hijra population in Bangladesh historically faces exclusion and discrimination at multiple levels in society [ 13 ] due to socio-cultural norms and sexual orientation [ 14 ]. The historical marginalization and subjugation of hijra can be traced back to the British colonial era, when the group was consistently criminalized and classified as ‘eunuch’, along with nonnormative, gender, and sexual minorities [ 15 ]. The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 declared hijra to be criminals, and incorporated the 377 acts that forbade unnatural sex and used as a means of preventing sex between men and hijra [ 4 , 15 ]. Contemporary and postcolonial representations of hijra continue colonial influence, with Bangladeshi people refusing to accept hijra presence and community interactions due to cultural norms [ 3 , 16 ]. Besides, the current social system does not acknowledge hijra as human beings or accept them favorably, and they are harshly excluded from social, cultural, educational, legal, and medical facilities because of their non-binary identities [ 3 , 14 ] The hijra often experiences exclusion that begins within their homes and later evolves into isolation and ostracization in schools. Such experience often leads them to drop out of school, which makes them less likely to gain employment in the formal sector. In many cases, the hijra tends to leave their homes due to the social stigma and condemnation of their life choices from family members [ 10 ]. Consequently, they end up living in communities of hijra under a leader ( Guru ) who socializes them into their lifestyle [ 2 ].

The hijra population in Bangladesh ranges from 10,000 to 50,000 out of 160 million people [ 17 ] which accounts for only a fraction of Bangladesh's overall population, they have long been regarded as an isolated and backward community [ 14 ]. The hijra community is marginalized in economic, social, and political life [ 3 ]. For an extended period, the hijra was also denied access to social institutions and services, including education, housing, and primary healthcare [ 10 ]. They also experience inequality in their fundamental human rights to justice and development [ 5 , 10 ]. In addition to societal prejudice, the hijra people regularly experience violence, oppression, and abuse [ 10 ]. The hijra in Bangladesh is typically denied basic citizenship rights, including inheritance, property ownership, employment, and medical care [ 10 ].

They also tend to live a miserable life with little to no access to healthcare, social security, or legal resources. Most of the hijra cannot access healthcare services due to discrimination from the doctors and nurses [ 2 ]. However, they rarely visit government healthcare centers due to such discrimination. They cannot even participate in cultural gatherings and religious festivals such as family programs, weddings, and funerals [ 18 ]. Additionally, they are also unable to access legal rights and often face ill-treatment when filing a grievance or discrimination case if they experience discrimination [ 2 , 3 ]. Similarly, they lack voting rights [ 18 ] and cannot participate in national elections as they lack national identity cards and decision-making ability. Their opinion and ability to participate in political spheres are disregarded by the general public [ 19 ].

Hijra in Bangladesh faces numerous social, cultural, economic, and political hurdles. Many have faced severe prejudice and discrimination due to their sexual orientation [ 14 ]. However, awareness of gender-diverse communities is growing in developing countries [ 20 , 21 ], and the government of Bangladesh is striving to achieve a country where every person, regardless of gender and sexuality, can live a quality life with human rights, dignity, and social justice [ 22 ]. Bangladesh's government is integrating the hijra community into mainstream society by legally recognizing them as a third gender and incentivizing companies to employ them to promote social inclusion [ 23 ]. In addition to LR, the ‘Livelihood Development Program for the Hijra Community in Bangladesh’ is also a commendable initiative of the government, as it aims to provide education, training, and income-generating opportunities for young hijra individuals while also ensuring social security for elderly members of the community [ 24 ].

Existing research conducted on the lifestyles of the hijra [ 10 ], as well as their discrimination and social exclusion [ 14 ], and these studies highlighted the period before the official recognition of the hijra . Most of the studies regarding the impact of legal recognition on the lives of third gender people were conducted in other cities of Bangladesh, such as Dhaka, Chittagong, Mymensingh, Narayanganj, and Rajshahi [ 2 , 22 , 25 ] but no study has been found to carry out on the impact of LR on the lives of the third gender community in Khulna district of Bangladesh. Additionally, the study is significant for the inclusion of the third gender in mainstream society's all spheres of life, including social, economic, political, legal, and healthcare sectors, in Bangladesh to achieve United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10, which calls for the reduction of inequalities by 2030. Therefore, considering these research gaps the present study intends to explore to what extent the socio-cultural, economic, political, healthcare, and legal aspects of the lives of the third gender community have changed by their official recognition.

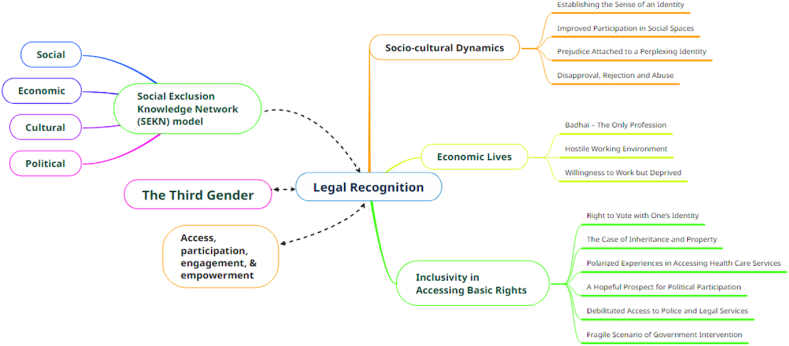

1.1. Theoretical framework

We followed the Social Exclusion Knowledge Network (SEKN) model developed by Popay, Escorel [ 26 ] to understand the impact of LR on the lives of the third gender in Khulna district of Bangladesh ( Fig. 1 ). Th mode states that social exclusion is caused by unequal power dynamics that operate in four interconnected dimensions: social, political, economic, and cultural. These dimensions operate at different levels, including individual, household, group, community, country, and global. The application of the SEKN model clarifies the diverse experiences that third gender people have following their legal recognition. According to Levitas, Pantazis [ 27 ], social exclusion is a multifaceted term that includes being denied access to resources, services, and rights as well as being unable to engage in relationships and social activities that the majority of individuals in society may participate in.

Conceptual framework of the study based on Social Exclusion Knowledge Network (SEKN) model.

Social aspects in exclusion comprises of restricted or no access to services such as education, health, legal and social services which develop from disrupted social safeguards and cohesion often embedded in kinship, family, neighbour, and community. In addition, cultural aspects of exclusion include confinement of individual or groups norms, behaviours, practices, and lifestyle. Depriving citizens of their rights and limiting their participation in laws, constitutions and decision-making are political dimensions of exclusion. Barriers to employment and prospects for a living, such as poor income, housing, land, or working conditions is referred to as economic aspects of exclusion. Focusing on the shifts in power dynamics within the SEKN model's four dimensions helps to demonstrate how legal recognition affects the lives of the third gender.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. research design and study settings.

The study was exploratory and tried to explore the impact of LR on the lives of the third gender community in Khulna City Corporation of Bangladesh. A qualitative approach was undertaken for the study because it provided a detailed understanding of the lives of the third gender community and how their lives had been changed after their LR by talking directly with people, going to their places of abode, and allowing them to tell their stories [ 28 ]. We selected Khulna City Corporation under Khulna district as the area of study because there is no evident literature that has upheld the state of affairs of the third gender community after their LR in this area. The study was conducted following two qualitative research methods, including in-depth interviews (IDIs) and key informant interviews (KIIs). The IDIs method is primarily used to obtain a sense of how individuals view their situation and what their experiences have been around the research topic under consideration [ 29 ]. On the other hand, KIIs were carried out with participants who had working experience of at least five years with the third gender and their multidimensional perspectives on this issue might help to formulate further policy implications.

2.2. Participants and sampling

To attain the study objectives, some attributes regarding participants for IDIs and KIIs were made. For IDIs, the attributes considered in selecting the participants were: i) Participants who identified them as hijra (Those who are neither male nor female by birth and the castrated men); ii) Participants had to be between 18 and 60 years of age; iii) Transgender people will not be included in this study; and iv) Participants had to reside in the study area for more than 5 consecutive years. Besides, for KIIs, the criteria considered in selecting the participants were: i) Participants had to be working with or in the hijra community for 5 years, particularly in Khulna district. To conduct the study, snowball sampling (chain-referral sampling) was used to collect data from the hijra community residing in Khulna City Corporation. Snowball sampling is employed because the investigated population is ‘hidden’ due to the low number of potential participants or the sensitivity of the topic [ 30 ]. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [ 31 ], the total population of the hijra residing in Khulna City is 109. Moreover, considering the sensitivity of the themes within the topic, the researcher felt it was convenient to use snowball sampling. We collected data from 13 participants in the study area, and it is evident from previous studies that sample size is not important for qualitative research but the depth of the information [ 32 , 33 ].

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews by SS from October to November 2022 by following semi-structured interview schedules. The semi-structured interview questions focused on their experiences regarding access to work, healthcare, and legal services, their participation in social events and politics or political activities. In addition, open-ended questions were asked to assess their experiences regarding the changes in their political, legal, healthcare, social, and cultural lives after their LR as third gender. Moreover, data were collected with the assistance of Rural and Urban Poor's Partner for Social Advancement (RUPSA), a non-governmental organization working with the hijra community in Khulna. The researchers were able to communicate with three different leaders ( Guru Ma is the head of a hijra community in a specific area) of the hijra community who further introduced the researcher to other participants. Before data collection, the researcher discusses the objectives of the study and obtains informed verbal consent from the participants. During the interviews, the researcher employed both notetaking and audio recording as data collection tools. The interviews were conducted in Bengali, considering the native language of the participants and their understanding as well as to ensure the greater accuracy of the information. Permission was obtained from Guruma before data collection, and she was present during the data collection period. Besides, the KIIs were carried out at the participants' respective workplaces due to their convenience. Upon conducting the ninth interview, it seemed that the investigation had reached a point of saturation. As a result, data collection was halted after the thirteen interviews. In qualitative research, the sample size is not as crucial for making generalizations; rather, the depth of the data is more important [ 33 ]. Each interview took on average 25–30 min. None of the contacted participants refused to drop out of the interview.

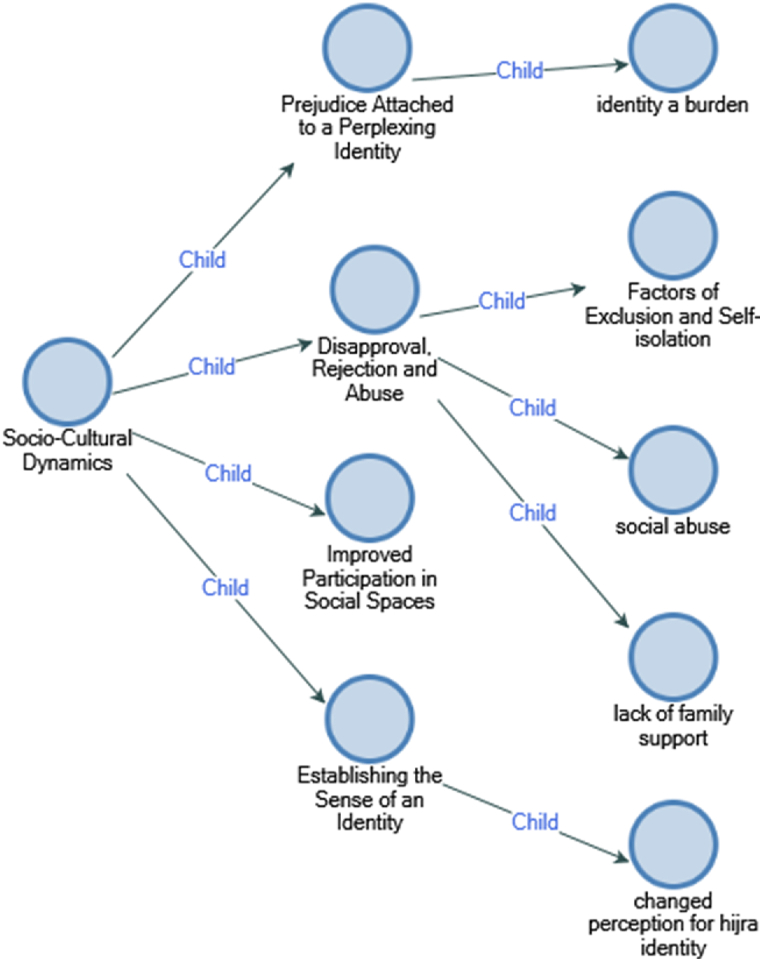

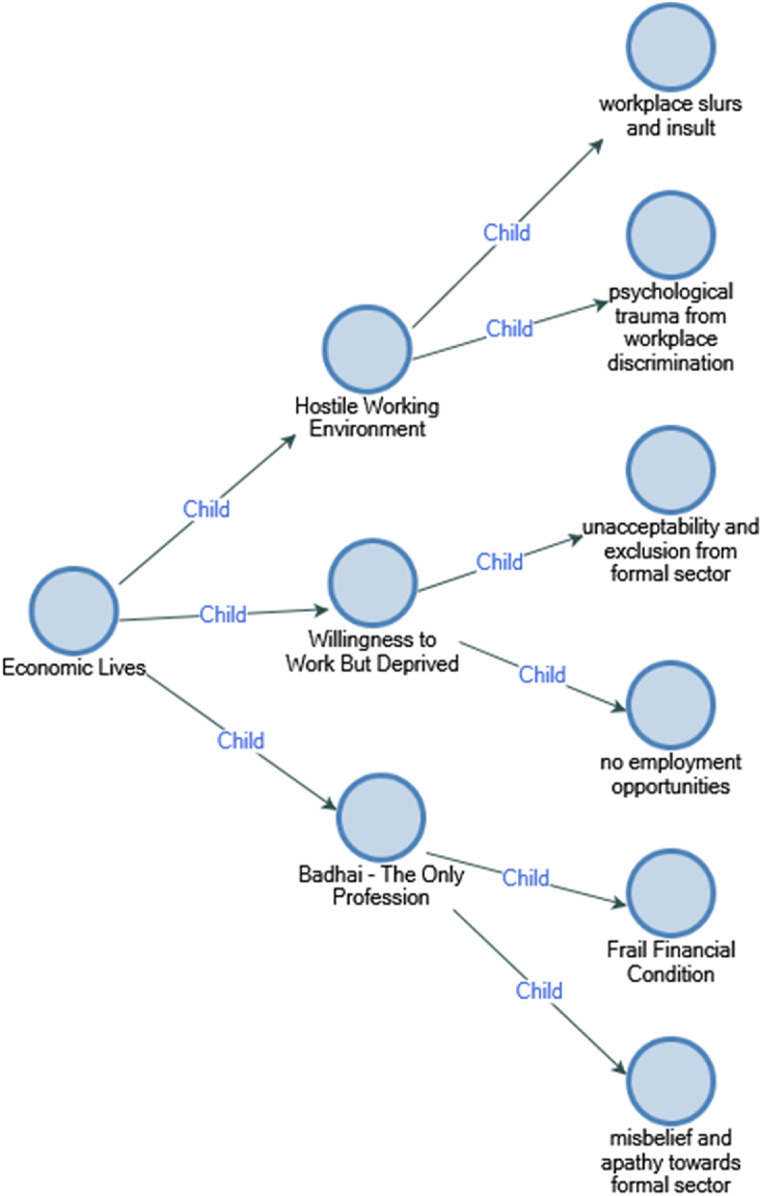

2.4. Data analysis

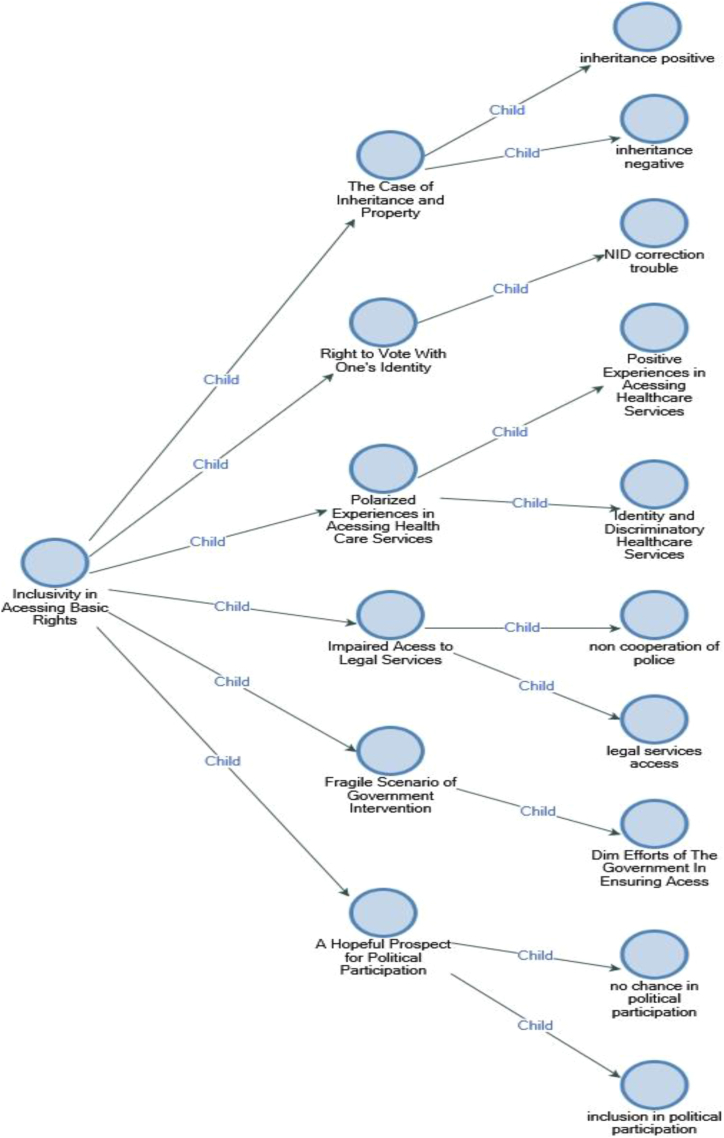

The interviews were recorded with the verbal consent of the participants. These were later transcribed verbatim into English, and the transcription was done in Microsoft Word 2016. The transcriptions were not returned to the participants for any feedback. The researcher used qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS), NVivo 12. The transcribed files were uploaded in Nvivo 12 before commencing coding. While analyzing the data, the researcher gave priority to exploring the text's meaning because a proper analysis requires developing the meanings of the interviews, highlighting the perspectives of the research participants, and providing new perspectives from the researchers [ 34 ]. Due to the high flexibility of interviews, the researcher used thematic analysis with narratives to identify and interpret the patterns (themes) within the data [ 35 ]. Relevant text from the participants was coded into different nodes, which were aggregated to form a theme. NVivo 12 software generated thirteen themes under three domains. In addition, three figures ( Fig. 2 , Fig. 3 , Fig. 4 ) highlight the coding tree for the major themes identified from IDIs and KIIs. Codes relate to socio-cultural dynamics, economic lives, and inclusivity in accessing basic rights. For each root code, subordinate child codes elaborate the description. All the root and child codes were generated by using computer-assisted (or aided) qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS), NVivo 12. The researchers kept possession of all the verbatim transcriptions and audio recordings, which were stored in computer files.

Coding tree of major thematic codes generated from IDIs and KIIs under ‘Socio-cultural Dynamics’.

Coding tree of major thematic codes generated from IDIs and KIIs under ‘Economic Lives’.

Coding tree of major thematic codes generated from IDIs and KIIs under ‘Inclusivity in Accessing Basic Rights’.

3.1. Personal profile of the participants

Ten participants who were identified as third gender participated in IDI, and their ages ranged from 28 to 45 years ( Table 1 ). Of the ten, eight of them were Muslims, and two followed the Sanatan (Hinduism is treated as Sanatan ) religion. Regarding education, half of them had a primary level of education, and half of them had a secondary level of education. All of them are involved in Badhai as their occupation. On the other hand, three participants were selected as KII participants, and their average age was 42 years. The participants were selected to offer valuable insights from multiple viewpoints. The KII participants were a government employee, an academician, and the executive director of a local NGO. All of the participants have been directly involved with working with or in the third gender community in Khulna City.

Profile of the participants.

3.2. Socio-cultural dynamics of the third gender after LR

3.2.1. establishing a sense of identity.

All the participants (N = 10) of IDI have mentioned that the LR of the third gender has permitted them to make a national identification card (NID), allowing them to have a sense of identity. In addition, they felt more accepted and were able to express who they were as individuals because of the LR. Regarding this, a participant specified that

“We have an identity now. Wherever we go now, we can say that we have our own identity. In the past, we could not talk too much about our identity, but now we can do that easily. There is no need to keep our heads down anymore. We achieved the recognition of our society. We can proudly say that we are the citizens of our country.” (IDI Participant 6)

Participants mentioned that the LR has influenced people's attitudes toward the third gender community to some extent. Previously, people in society viewed the community negatively. Regarding the change in perception and increased interaction, a participant mentioned that-

“Before 2013, people believed that socializing with hijra was embarrassing. People began to have a more positive attitude toward the hijra community after 2013, and especially after 2019. This did not happen suddenly; rather, it took time. Now, the acceptance of the hijra is increasing in all areas of life. If a hijra goes somewhere, she will not come empty-handed. Before 2013, the situation was worse.” (IDI Participant 9)

3.2.2. Improved participation in social spaces

Since the LR of the third gender, the community has enjoyed a sense of freedom and participation in public gatherings. The community had limited freedom within society because they did not subscribe to the traditional binary gender identity. The IDI participants stated that since the LR, they can participate in religious ceremonies such as Eid and Durga Puja , cultural ceremonies such as Pahela Baisakh , and social gatherings such as weddings, national events, and programs. A participant commented on this matter:

“Yes, I attend these programs. We celebrate Eid like other people, and those who are of the Sanatan religion among us also celebrate their puja. We do not face any problems regarding these social and religious functions.” (IDI Participant 6)

3.2.3. Prejudice attached to a perplexing identity

The participants have responded positively towards the improvement in social participation and garnering a sense of identity after the LR. However, the participants still have to deal with the prejudice and taboo associated with the word ‘ hijra ’ by which they are commonly known. Furthermore, the notion of perplexing identity is a loophole in LR that needs amendment. Most of the participants in IDI and KII (N = 7) voiced the issue of prejudice associated with their gender identity. One of the participants stated that

“People say, ‘Look, a hijra has come here.’ This stigma associated with the hijra word follows the person throughout her life. It cannot be removed. This problem can only be solved if people’s perspectives shift.” (IDI Participant 7)

3.2.4. Disapproval, rejection, and abuse

Since childhood, the third gender community has faced disapproval, rejection, and abuse because of their gender identity. They often experience disapproval and abuse from their neighbors and school, and they fail to garner family support. The prejudicial perception of the general mass has not been dismissed, despite the LR. Most of the IDI participants (N = 9) have stated that they were rejected by their families due to their gender identity and have not been able to properly reconnect with them yet. A participant voiced their opinion regarding this matter with regret:

“I came here because the people of society condemned me. Also, my family did not approve of it. Even though a family wants to accept the gender identity of a child, due to several social factors, they cannot do so. At one point, the family encourages the child to go to a different place to live.” (IDI Participant 7)

3.3. Economic lives of the third gender after LR

3.3.1. badhai: the only profession.

Badhai is the traditional profession of the hijra community, which includes songs, prayers, dance at weddings, births, and other heteronormative celebrations. Those who adopt the hijra life partake in engaging in badhai, which is their sole profession. All the IDI participants (N = 10) are engaged in badhai . The concept of badhai can be more clearly understood through a participant's response. She mentions that

“I am doing ‘badhai’ which is the main job for our hijra group. We celebrate births, weddings, and many other social programs and collect money from these events. It is called ‘badhai’ in our language.” (IDI Participant 6)

The third gender community tends to hold a strong perception of apathy and inferiority towards working in the formal sector, which has been highlighted in a participant's statement:

“When they come to the hijra community under the Guru Ma, they are made to think differently. The hijras do not want to enter the mainstream because they have mentally programmed themselves to believe that the main task of the hijras is to engage in Badhai and nothing else.” (IDI Participant 9)

However , the lack of employment opportunities in the formal sector for the hijra community and their unacceptability and exclusion from mainstream society, has kept the third gender community rooted in engaging in the stereotyped occupation known as badhai .

3.3.2. Hostile working environment

All participants engage in badhai, which requires interacting with the people in society, and nearly all the participants in IDI (N = 9) of the third gender community have reported a hostile working environment. They also noted that criticism and negative attitudes from the public are an everyday phenomenon in their daily working lives. One participant voiced her opinion:

“Most of the people are rude to us and do not want us to enter their homes. They shout at us, act mean, and try to drive us away. One day I went to a house where a newborn baby was present. They rudely told us to go away and that they would not give us any money. Furthermore, they said, ‘The government is there for you people.’ ‘It will look after you.’ Afterward, they shut the door and would not open it. We came back without getting a chance to hold the baby.”(IDI Participant 4)

3.4. Willingness to work but denied

The LR acknowledges the hijra community as a separate gender (third gender) along with which comes their right to work. Despite their willingness, they are barred from entering the formal sector due to the general public's unacceptability of their inclusion and little to no employment opportunities. Most of the participants (N = 7) in the third gender community expressed their desire to work. However, no employment opportunities and their unacceptability and exclusion from the formal sector have kept them rooted in engaging in badhai . One of the participants in IDI states that

“Yes, I want to live my life like the rest of the general population. I want to live my life and work with my head held high. But I do not have anyone to assist me. I think it would be better if I could leave all this behind and do something else. I wish that people knew me not because of being a hijra, but rather because of my work.” (IDI Participant 3)

Two participants have also mentioned that they have worked for a short period in the formal sector. However, they were subjected to discrimination and harassment. Despite their determination, in the end, they were excluded from the formal sector. Regarding this, a participant articulated her experience:

“Yes, I did work in the formal sector. I worked at an electronics showroom that sold refrigerators, air conditioners, and televisions. The coworkers were against my staying there. They said, ‘You are a hijra.’ ‘You are incapable of handling these tasks.’ After two days of work, they told me, ‘There is no need for you to be here. You may go. You do not have to work here. This place is not for you.’ There are no options for us to be involved in any other work as hijra. Society has created those barriers for us.” (IDI Participant 4)

3.5. Inclusivity in accessing basic rights of the third gender after LR

3.5.1. right to vote with one's identity.

All the participants (N = 10) of the third gender community held a national identity card and mentioned that they did not face any difficulty in voting in national and local elections and were able to cast their votes for their candidate of choice. A participant provided her statement regarding this issue:

“No, I did not face any problems. I was able to vote like the rest of the people by standing in a line, waiting for my turn, and casting my vote. I chose, selected my candidate, and gave my vote accordingly.” (IDI Participant 5)

The LR has provided the third gender community with the right to exercise their right to vote with their own identity, from which they were previously barred.

3.5.2. The case of inheritance and property

The third gender community often faces exclusion from their family inheritance and cannot purchase any assets because of their poor economic condition. Most of the participants (N = 6) in the third gender community expressed that they do not have any inherited property or assets. One of them indicated that she was excluded from it and could be subjected to acts of violence if she attempted to claim her inheritance. She remarked,

“I do not have any headaches to claim it. I am hijra. If I go to claim it, I might get murdered by my brothers. They are goons. When I understood that I would be harmed if I asked for my property, I lost hope. They have grabbed it and are enjoying it.” (IDI Participant 2)

In Bangladesh, the inheritance law recognizes only two genders, male and female, and does not recognize the rights of third gender people to inherit property. Furthermore, there is no specific law regarding inheritance among hijra in Bangladesh. However, Article 42 of the Constitution of Bangladesh guarantees the property right, which includes the right to inherit property. Moreover, some participants (N = 4) mentioned that they have been able to inherit some sort of property from their parents. One participant also mentioned that she was able to buy some assets from the money in her inheritance. The LR of the hijra is a positive step toward improving their inheritance rights. The neighboring country of Pakistan passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act in 2018 [ 36 ], and in the following year, India also passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act [ 37 ] to recognize the rights of transgender individuals, including inheritance rights. However, in Bangladesh, some hijra people can access their inheritance property rights according to the constitution, but no specific law has been passed yet. As a result, some hijra people often face discrimination when it comes to inheriting property due to societal stigmatization and a lack of legal protection.

3.5.3. Polarized experiences in accessing healthcare services

Most of the participants have reported severe incidents of negligence, avoidance, ill-treatment, and verbal and sexual abuse they encountered when accessing healthcare services. They also encountered stigma attached to their identity and narrated that their identity was a prime reason for encountering such discriminatory healthcare services. One participant narrated her experience:

“I went to visit a doctor in a government hospital in Khulna. Upon going there, they refused to give me a ticket. They were telling me to show my identity card. I showed them, and they told me to wait. I kept waiting, but they were not allowing me because a hijra had come. After that, the doctor did not see me properly. He just asked a few questions, prescribed some medicines, and told me to go hurriedly. This is what they do. When we go to any hospital, they tell us that a hijra has come and do not allow us to enter. We do not get healthcare services like the rest of the general population.” (IDI Participant 1)

3.5.4. A hopeful prospect for political participation

The majority of participants (N = 7) of the third gender community have stated that they attend political rallies, meetings, and seminars. They have not faced any discrimination participating in political meetings. However, they only participate but cannot voice out their demands at these events. In addition, none of them participated in national or local-level politics. A participant in IDI outlined her opinion:

“What is the benefit of legal recognition? Are we able to be vocal about our issues? There are no people who represent us in the parliament. The members of parliament are only vocal about their issues. If there was a representative from our community in the parliament, then our issues would be addressed. Now, there are people of the third gender community who are becoming chairman, vice-chairman, and members. Are these not our attainments?” (IDI Participant 9)

3.5.5. Debilitated access to police and legal services

The third gender community is often barred from accessing police and legal services. Most of the participants (N = 5) have stated that they have faced incidents of neglect, prejudice, avoidance, and discrimination while accessing police help. They expressed that the police do not want to file complaints and pay any heed to the problems of the third gender community. Furthermore, they are also mocked and taunted by the police officers. A participant narrated such an experience:

“If we go to the police for anything, they do not pay heed to it. Now, there is a police helpline where you can dial 999 and seek the help of a police officer. So, when we call, they do not understand that we are hijra upon listening to our voice. But when they come and see that the hijra has called, they just give us false hopes, saying we will look into the matter. They pay no attention to our harassment complaints and do not take our matters seriously.”(IDI Participant 2)

3.5.6. Fragile scenario of government interventions

Despite the LR, the government has failed to ensure basic rights for the third gender community in Bangladesh. A participant in KII mentioned that the government is providing a special allowance for the people of the third gender community, providing stipends for school-going third gender members, and providing them training to make them self-sufficient and develop skills that foster their income-earning capacity. Except for these, the government has not introduced any programs aiming to serve the necessities, such as education, accommodation, and healthcare. One of the key informants stated that-

“I think if you talk about giving the hijra an identity and providing them with a national identity card and the right to vote. Then you can say that the legal recognition of the third gender has benefited that community. However, issues about their health, property, employment, family, banking, education, etc. are some of the areas where legal recognition has not been able to make that much of an impact.” (KII Participant 2)

4. Discussion

The hijra community in Bangladesh has historically been the most marginalized, neglected, and vulnerable sexual minority group and suffers from extreme economic, social, cultural, and political exclusion [ 14 ]. However, the Cabinet of Bangladesh issued a gazette in November 2013, permitting gender non-confirming individuals to identify as ‘third gender’ instead of male or female on all official forms, passports, and national identification cards (NIDs) [ 3 ]. The present study attempted to assess the impact of LR on the lives of the third gender, particularly their socio-cultural dynamics, economic lives, and inclusivity in accessing basic rights after their LR in the context of Khulna City of Bangladesh.

Regarding socio-cultural dynamics, we found that the LR permitted the third gender community to establish a sense of identity and enhanced their participation in social spheres, which is inconsistent with the findings of previous studies [ 18 , 19 ] which stated that the third gender community was unable to attend social and cultural events such as family gatherings, weddings, funerals, and cultural and religious festivals. Such disparities might be explained by a handful of people's acceptance of this community, their rising involvement in public spheres, and, to some extent, a change in the wider public's mindset.

We also found that the third gender community still had to endure social stigma and taboo associated with being a member of that community despite their improved participation, which was also reported in another study conducted in Bangladesh [ 9 ]. This might be illustrated by prejudiced socio-cultural norms as a major factor in their discrimination and stigmatization [ 14 ]. Furthermore, the findings of the present study depict that the third gender members have been castrated from their families and still have not been able to reconnect with them even after their official recognition. This finding is congruent with the previous studies conducted in India [ 13 ] and Bangladesh [ 19 ]. They also leave their family willingly because of their family welfare and their condemnation by society [ 38 ].

Regarding the economic lives of the third gender, along with previous studies, we found that all the third gender people engaged in their traditional, informal job, ‘ Badhai’ [ 2 , 10 ]. Lack of education, skills, and employment opportunities, and the general people's unacceptability were the prime hindrances in this pursuit [ 2 , 14 ]. Findings revealed that the participants held a strong apathy and sense of inferiority in working in formal job sectors due to their negative experiences and perceptions, which is aligned with a previous study [ 39 ]. Furthermore, Jebin and Farhana [ 38 ] also mentioned that the general public does not appreciate a third gender person working with them. Prejudice, taboo, and stigma attached to the hijra identity are possible reasons for their disregard by the public, which need further investigation.

Regarding inclusivity in accessing basic rights, we found that all participants were able to participate in voting at national and local elections without undergoing any discrimination, which is inconsistent with the findings of previous studies [ 18 , 19 ] that found the third gender community faced exclusion from participating in voting. These discrepancies might be attributed to the legal recognition of the third gender, which increased their attainment of voting rights. Consistent with the findings of a prior study [ 22 ], we also found that the third gender community reported that their economic rights to inheritance and property were violated. This could be explained by the exclusion of the third gender from the family inheritance and poor economic conditions [ 14 , 19 , 38 ].

Consistent with the existing literature, we found that the third gender community faced discrimination in accessing healthcare services, which came in the form of mistreatment, verbal and sexual abuse, rejection, neglect, and avoidance [ 2 , 40 , 41 ]. Regarding access to police and legal services, we found that the hijra faces severe instances of discrimination while accessing police services, which was also reported by Jebin and Farhana [ 38 ] that third gender people do not receive any police support due to fear and harassment from the police. The study also highlighted the scenario of the government's frail intervention in ensuring necessities for the third gender community such as employment, healthcare, education, and accommodation, even after a decade of LR, which has been highlighted in multiple studies [ 2 , 19 , 38 , 39 , 42 ].

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our study on the impact of legal recognition on the third gender community has some strengths and limitations. We conducted the first exploratory qualitative study in Khulna City, enabling us to gain a deeper understanding of the participants' experiences. Furthermore, we collected data through face-to-face interviews, which enhanced the accuracy and clarity of the participants' perceptions. However, we acknowledge that our study's scope is limited to the qualitative experiences of a small group of hijra in one city in Bangladesh, and our findings cannot be generalized for the third gender community nationally. Our study's cross-sectional nature may also limit the causal inferences and recall bias may have influenced our findings due to self-reported data. Lastly, our qualitative approach has its limitations, and we suggest further research using a triangulation of both qualitative and quantitative research with a representative sample at the national level to better understand the situation of the third gender community after their legal recognition.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

The study aimed to investigate the impact of legal recognition on the lives of the third gender community in the Khulna district of Bangladesh. It was found that the legal recognition provided them with a sense of identity and increased their social participation. However, their economic lives remained unaffected as they continued to face discrimination in their regular professions. While there has been progress in third gender's ability to vote and participate in politics, however, conditions in relation to inheritance, healthcare, and legal services have not improved after LR. Since they have encountered instances of violence, negligence, avoidance, exclusion, and discrimination while accessing inheritance, legal, and healthcare services. To address this issue, the study recommends implementing local awareness campaigns to promote acceptance and reduce social stigma toward the third gender community. Furthermore, professional training programs should be provided to help them achieve financial independence. Besides, the government should enact laws for the protection of the rights of the third gender community to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10, which aims to reduce inequalities by 2030 in Bangladesh.

Funding statement

The researchers did not receive any funds for this study.

Data availability statement

No archived data/repository was used for this study.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Clearance Committee of Khulna University, with the approval number: KUECC-2023/01/04. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. At first, the objective of the study was disclosed to the participants. Then, the participants were made aware of the fact that they were free to decline the study at any moment without any justification. Throughout the study, the anonymity of the participants and the confidentiality of the information were upheld.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shahinur Akter: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Shankha Saha: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28671 .

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

- 1. Nisar M.A. (UN)Becoming a man: legal consciousness of the third gender category in Pakistan. Gend. Soc. 2018;32(1):59–81. doi: 10.1177/0891243217740097. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Aziz A., Azhar S. 2019. Social Exclusion and Official Recognition of Hijra in Bangladesh. https://digital.library.txstate.edu/handle/10877/12901 [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Hossain A. The paradox of recognition: hijra, third gender and sexual rights in Bangladesh. Cult. Health Sex. 2017;19(12):1418–1431. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1317831. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Snigdha R.K. Auckland University of Technology; 2021. Beyond Binaries: an Ethnographic Study of Hijra in Dhaka, Bangladesh. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Chakrapani V. 2010. Hijras/transgender Women in India: HIV, Human Rights and Social Exclusion. https://archive.nyu.edu/bitstream/2451/33612/2/hijras_transgender_in_india.pdf Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Hahm S.C. Hague: International Institute of Social Studies; 2010. Striving to Survive: Human Security of the Hijra of Pakistan. http://hdl.handle.net/2105/8652 Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Wallen J. The Telegraph; 2019. Transgender Community in Bangladesh Finally Granted Full Voting Rights. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/climate-and-people/transgender-community-bangladesh-finally-granted-full-voting/ Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Josim T. Hijra: Ak omimangshito Lingo (hijra: an unresolved gender) Ajker Prottasha. 2012;8:5d. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Shuvo H.S. Life of hijra in Bangladesh: challenges to accept in mainstream. International Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 2018;5(3):60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10840. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Khan S.I., et al. Living on the extreme margin: social exclusion of the transgender population (hijra) in Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2009;27(4):441. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i4.3388. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Karim M. Hijras now a separate gender. Dhaka Tribune. 2013;11:2013. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/bangladesh-others/43294/hijras-now-a-separate-gender Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Ahmed S. 2013. Recognition of ‘Hijra’as Third Gender in Bangladesh. https://archive.nyu.edu/handle/2451/42376 Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Kalra G., Shah N. The cultural, psychiatric, and sexuality aspects of hijras in India. Int. J. Transgenderism. 2013;14(4):171–181. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2013.876378. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Al-Mamun M., et al. Discrimination and social exclusion of third-gender population (Hijra) in Bangladesh: a brief review. Heliyon. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10840. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Hossain A. Hijras in South Asia: rethinking the dominant representations. The SAGE Handbook of Global Sexualities. 2020;1:404–421. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Husain S. Tritio Prokriti: Bangladesher Hijrader Arthoshamajik Chitro (hidden gender: a Book on socio-economic status of hijra community of Bangladesh) Dhaka: Sararitu. 2005 [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Chowdhury S. Transgender in Bangladesh: first school opens for trans students. BBC News. 2020 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-54838305 Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Islam S. A theoretical analysis of the legal status of transgender: Bangladesh perspective. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science. 2019;3(3):117–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Sifat R.I., Shafi F.Y. Exploring the nature of social exclusion of the hijra people in dhaka city. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2021;47(4):579–589. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2020.1859434. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Ibrahim A.M. LGBT rights in Africa and the discursive role of international human rights law. Afr. Hum. Right Law J. 2015;15(2):263–281. doi: 10.17159/1996-2096/2015/v15n2a2. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Divan V., Cortez C., Smelyanskaya M., Keatley J. Transgender social inclusion and equality: a pivotal path to development. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2016;19 doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.3.20803. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Amanullah A., et al. Human rights violations and associated factors of the Hijras in Bangladesh—a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269375. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Alzjazeera . 2021. Tax Rebate for Bangladesh Companies Hiring Transgender People. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/4/tax-rebate-for-bangladesh-companies-hiring-transgender-people Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Department of Social Services . 2022. Livelihood Development Program for the Hijra Community in Bangladesh. https://www.facebook.com/dss.gov.bd/videos/hijra-or-transgender-livelihood-development-program-in-bangladesh/1605736416213598/ Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Daize A.S., Masnun E. Exploring the socio-economic and cultural status of third gender community in Bangladesh. Jagannath University Journal of Arts. 2019;9(2):181–192. https://jnu.ac.bd/journal/assets/pdf/9_2_373.pdf Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Popay J., et al. 2008. Understanding and Tackling Social Exclusion. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Levitas R., et al. 2007. The Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Social Exclusion. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Creswell J.W. second ed. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. San Francisco: Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Morris A. first ed. Sage Publications; London: 2015. A Practical Introduction to In-Depth Interviewing. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Waters J. Snowball sampling: a cautionary tale involving a study of older drug users. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2015;18(4):367–380. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2014.953316. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics; Dhaka: 2022. Population & Housing Census 2022: Preliminary Report. http://www.bbs.gov.bd/site/page/47856ad0-7e1c-4aab-bd78-892733bc06eb/Population-and-Housing-Census Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Razu S.R., et al. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from Bangladesh. Front. Public Health. 2021:1024. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Bryman A. Oxford university press; 2016. Social Research Methods. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Kvale S., Brinkmann S. Sage Publications; Los Angeles: 2009. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Bazeley P. Sage Publications; 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis : Practical Strategies. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Rana A.A. 2020. Transgenders and Their Protection under Pakistani Law. Courting the Law(Courting the Law, August 8, 2020) https://courtingthelaw.com/2020/07/27/commentary/transgenders-and-their-protectionunder-pakistani-law/ Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Bhattacharya S., Ghosh D., Purkayastha B. ‘Transgender persons (protection of rights) act’of India: an analysis of substantive access to rights of a transgender community. Journal of Human Rights Practice. 2022;14(2):676–697. doi: 10.1093/jhuman/huac004. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Jebin L., Farhana U. The rights of Hijra in Bangladesh: an overview. Journal of Nazrul University. 2015;3(1&2) [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Safa N. Inclusion of excluded: integrating need based concerns of hijra population in mainstream development. Sociology and Anthropology. 2016;4(6):450–458. doi: 10.13189/sa.2016.040603. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Sarker M.G.F. Conference: the 10th International Graduate Students Conference on Population and Public Health Sciences. The College of Public Health Sciences; Thailand: 2019. Discrimination against Hijra (Transgender) in accessing Bangladesh public healthcare services. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Khan A., et al. Barriers in access to healthcare services for individuals with disorders of sex differentiation in Bangladesh: an analysis of regional representative cross-sectional data. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20(1):1261. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09284-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Mahmood K.S. The Daily Star. The Daily Star; Dhaka: 2018. Right to inheritance of the hijras in Bangladesh. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (2.2 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

THE THIRD GENDER: STAIN AND PAIN

2018, Vishwabharati Research Centre

The comprehensive compendium The Third Gender: Stain and Pain is packed with prodigious research papers, articles and case studies of well-versed academicians from all over India. The anthology addresses the myriad facets of a transgenders' life. Their problems of social identity, inequality, marginalisation, social exclusion, health care issues, documentation, education, unemployment, and poverty have been discoursed from social, political, economic, cultural and jurisprudence along with scientific angles. The book incorporates not only the troubles and deplorable plights but also intimates some resolutions that can mitigate the embarrassing abasement of the Third Gender.