- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

- 3 minute read

- 47.9K views

Table of Contents

Choosing an optimal research methodology is crucial for the success of any research project. The methodology you select will determine the type of data you collect, how you collect it, and how you analyse it. Understanding the different types of research methods available along with their strengths and weaknesses, is thus imperative to make an informed decision.

Understanding different research methods:

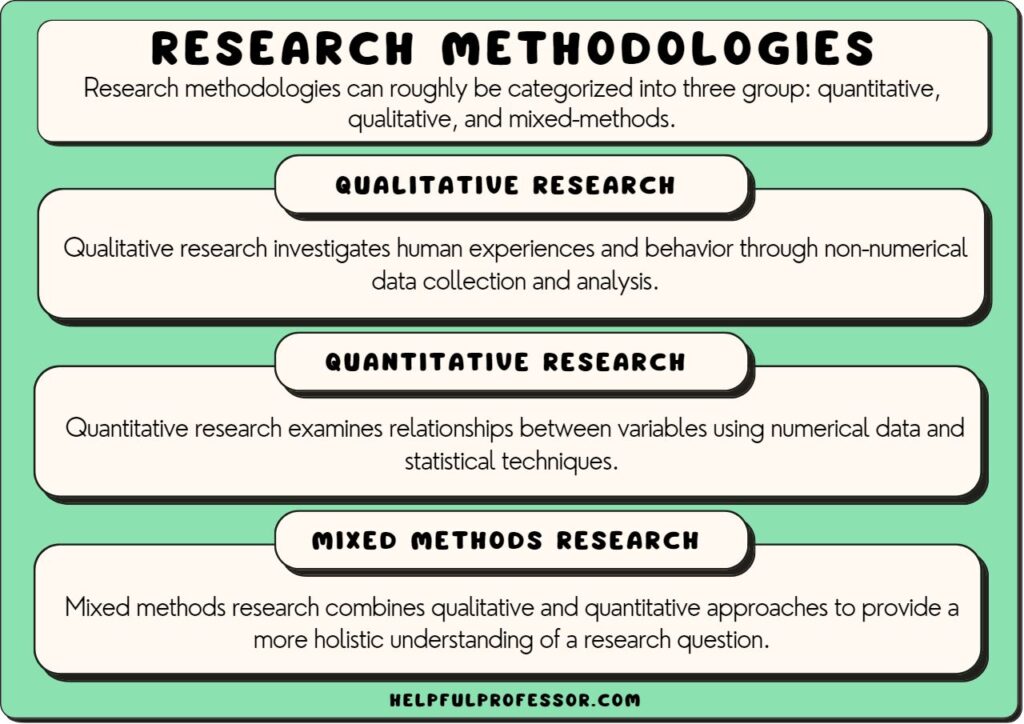

There are several research methods available depending on the type of study you are conducting, i.e., whether it is laboratory-based, clinical, epidemiological, or survey based . Some common methodologies include qualitative research, quantitative research, experimental research, survey-based research, and action research. Each method can be opted for and modified, depending on the type of research hypotheses and objectives.

Qualitative vs quantitative research:

When deciding on a research methodology, one of the key factors to consider is whether your research will be qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative research is used to understand people’s experiences, concepts, thoughts, or behaviours . Quantitative research, on the contrary, deals with numbers, graphs, and charts, and is used to test or confirm hypotheses, assumptions, and theories.

Qualitative research methodology:

Qualitative research is often used to examine issues that are not well understood, and to gather additional insights on these topics. Qualitative research methods include open-ended survey questions, observations of behaviours described through words, and reviews of literature that has explored similar theories and ideas. These methods are used to understand how language is used in real-world situations, identify common themes or overarching ideas, and describe and interpret various texts. Data analysis for qualitative research typically includes discourse analysis, thematic analysis, and textual analysis.

Quantitative research methodology:

The goal of quantitative research is to test hypotheses, confirm assumptions and theories, and determine cause-and-effect relationships. Quantitative research methods include experiments, close-ended survey questions, and countable and numbered observations. Data analysis for quantitative research relies heavily on statistical methods.

Analysing qualitative vs quantitative data:

The methods used for data analysis also differ for qualitative and quantitative research. As mentioned earlier, quantitative data is generally analysed using statistical methods and does not leave much room for speculation. It is more structured and follows a predetermined plan. In quantitative research, the researcher starts with a hypothesis and uses statistical methods to test it. Contrarily, methods used for qualitative data analysis can identify patterns and themes within the data, rather than provide statistical measures of the data. It is an iterative process, where the researcher goes back and forth trying to gauge the larger implications of the data through different perspectives and revising the analysis if required.

When to use qualitative vs quantitative research:

The choice between qualitative and quantitative research will depend on the gap that the research project aims to address, and specific objectives of the study. If the goal is to establish facts about a subject or topic, quantitative research is an appropriate choice. However, if the goal is to understand people’s experiences or perspectives, qualitative research may be more suitable.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, an understanding of the different research methods available, their applicability, advantages, and disadvantages is essential for making an informed decision on the best methodology for your project. If you need any additional guidance on which research methodology to opt for, you can head over to Elsevier Author Services (EAS). EAS experts will guide you throughout the process and help you choose the perfect methodology for your research goals.

Why is data validation important in research?

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

Writing a good review article

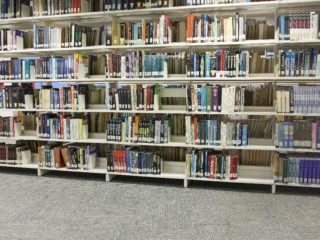

Scholarly Sources: What are They and Where can You Find Them?

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Methods | Definition, Types, Examples

Research methods are specific procedures for collecting and analysing data. Developing your research methods is an integral part of your research design . When planning your methods, there are two key decisions you will make.

First, decide how you will collect data . Your methods depend on what type of data you need to answer your research question :

- Qualitative vs quantitative : Will your data take the form of words or numbers?

- Primary vs secondary : Will you collect original data yourself, or will you use data that have already been collected by someone else?

- Descriptive vs experimental : Will you take measurements of something as it is, or will you perform an experiment?

Second, decide how you will analyse the data .

- For quantitative data, you can use statistical analysis methods to test relationships between variables.

- For qualitative data, you can use methods such as thematic analysis to interpret patterns and meanings in the data.

Table of contents

Methods for collecting data, examples of data collection methods, methods for analysing data, examples of data analysis methods, frequently asked questions about methodology.

Data are the information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question . The type of data you need depends on the aims of your research.

Qualitative vs quantitative data

Your choice of qualitative or quantitative data collection depends on the type of knowledge you want to develop.

For questions about ideas, experiences and meanings, or to study something that can’t be described numerically, collect qualitative data .

If you want to develop a more mechanistic understanding of a topic, or your research involves hypothesis testing , collect quantitative data .

| Qualitative | ||

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | . |

You can also take a mixed methods approach, where you use both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Primary vs secondary data

Primary data are any original information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question (e.g. through surveys , observations and experiments ). Secondary data are information that has already been collected by other researchers (e.g. in a government census or previous scientific studies).

If you are exploring a novel research question, you’ll probably need to collect primary data. But if you want to synthesise existing knowledge, analyse historical trends, or identify patterns on a large scale, secondary data might be a better choice.

| Primary | ||

|---|---|---|

| Secondary |

Descriptive vs experimental data

In descriptive research , you collect data about your study subject without intervening. The validity of your research will depend on your sampling method .

In experimental research , you systematically intervene in a process and measure the outcome. The validity of your research will depend on your experimental design .

To conduct an experiment, you need to be able to vary your independent variable , precisely measure your dependent variable, and control for confounding variables . If it’s practically and ethically possible, this method is the best choice for answering questions about cause and effect.

| Descriptive | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experimental |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

| Research method | Primary or secondary? | Qualitative or quantitative? | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Quantitative | To test cause-and-effect relationships. | |

| Primary | Quantitative | To understand general characteristics of a population. | |

| Interview/focus group | Primary | Qualitative | To gain more in-depth understanding of a topic. |

| Observation | Primary | Either | To understand how something occurs in its natural setting. |

| Secondary | Either | To situate your research in an existing body of work, or to evaluate trends within a research topic. | |

| Either | Either | To gain an in-depth understanding of a specific group or context, or when you don’t have the resources for a large study. |

Your data analysis methods will depend on the type of data you collect and how you prepare them for analysis.

Data can often be analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, survey responses could be analysed qualitatively by studying the meanings of responses or quantitatively by studying the frequencies of responses.

Qualitative analysis methods

Qualitative analysis is used to understand words, ideas, and experiences. You can use it to interpret data that were collected:

- From open-ended survey and interview questions, literature reviews, case studies, and other sources that use text rather than numbers.

- Using non-probability sampling methods .

Qualitative analysis tends to be quite flexible and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your choices and assumptions.

Quantitative analysis methods

Quantitative analysis uses numbers and statistics to understand frequencies, averages and correlations (in descriptive studies) or cause-and-effect relationships (in experiments).

You can use quantitative analysis to interpret data that were collected either:

- During an experiment.

- Using probability sampling methods .

Because the data are collected and analysed in a statistically valid way, the results of quantitative analysis can be easily standardised and shared among researchers.

| Research method | Qualitative or quantitative? | When to use |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | To analyse data collected in a statistically valid manner (e.g. from experiments, surveys, and observations). | |

| Meta-analysis | Quantitative | To statistically analyse the results of a large collection of studies. Can only be applied to studies that collected data in a statistically valid manner. |

| Qualitative | To analyse data collected from interviews, focus groups or textual sources. To understand general themes in the data and how they are communicated. | |

| Either | To analyse large volumes of textual or visual data collected from surveys, literature reviews, or other sources. Can be quantitative (i.e. frequencies of words) or qualitative (i.e. meanings of words). |

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

Is this article helpful?

More interesting articles.

- A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

- Between-Subjects Design | Examples, Pros & Cons

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

- Cluster Sampling | A Simple Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Confounding Variables | Definition, Examples & Controls

- Construct Validity | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Control Groups and Treatment Groups | Uses & Examples

- Controlled Experiments | Methods & Examples of Control

- Correlation vs Causation | Differences, Designs & Examples

- Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples

- Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples

- Data Cleaning | A Guide with Examples & Steps

- Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

- Explanatory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Explanatory vs Response Variables | Definitions & Examples

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- External Validity | Types, Threats & Examples

- Extraneous Variables | Examples, Types, Controls

- Face Validity | Guide with Definition & Examples

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

- Independent vs Dependent Variables | Definition & Examples

- Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation

- Inductive vs Deductive Research Approach (with Examples)

- Internal Validity | Definition, Threats & Examples

- Internal vs External Validity | Understanding Differences & Examples

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

- Mediator vs Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

- Mixed Methods Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Multistage Sampling | An Introductory Guide with Examples

- Naturalistic Observation | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Population vs Sample | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Primary Research | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

- Quasi-Experimental Design | Definition, Types & Examples

- Questionnaire Design | Methods, Question Types & Examples

- Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

- Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

- Reproducibility vs Replicability | Difference & Examples

- Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples

- Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Simple Random Sampling | Definition, Steps & Examples

- Stratified Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

- Systematic Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Textual Analysis | Guide, 3 Approaches & Examples

- The 4 Types of Reliability in Research | Definitions & Examples

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

- Transcribing an Interview | 5 Steps & Transcription Software

- Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Examples

- Types of Variables in Research | Definitions & Examples

- Unstructured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Are Control Variables | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

- What Is a Double-Barrelled Question?

- What Is a Double-Blind Study? | Introduction & Examples

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- What Is a Likert Scale? | Guide & Examples

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- What Is a Prospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

- What Is Concurrent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convenience Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convergent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Criterion Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Deductive Reasoning? | Explanation & Examples

- What Is Discriminant Validity? | Definition & Example

- What Is Ecological Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Ethnography? | Meaning, Guide & Examples

- What Is Non-Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

- What Is Predictive Validity? | Examples & Definition

- What Is Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Purposive Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods

- What Is Quota Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

- What Is Snowball Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- Within-Subjects Design | Explanation, Approaches, Examples

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

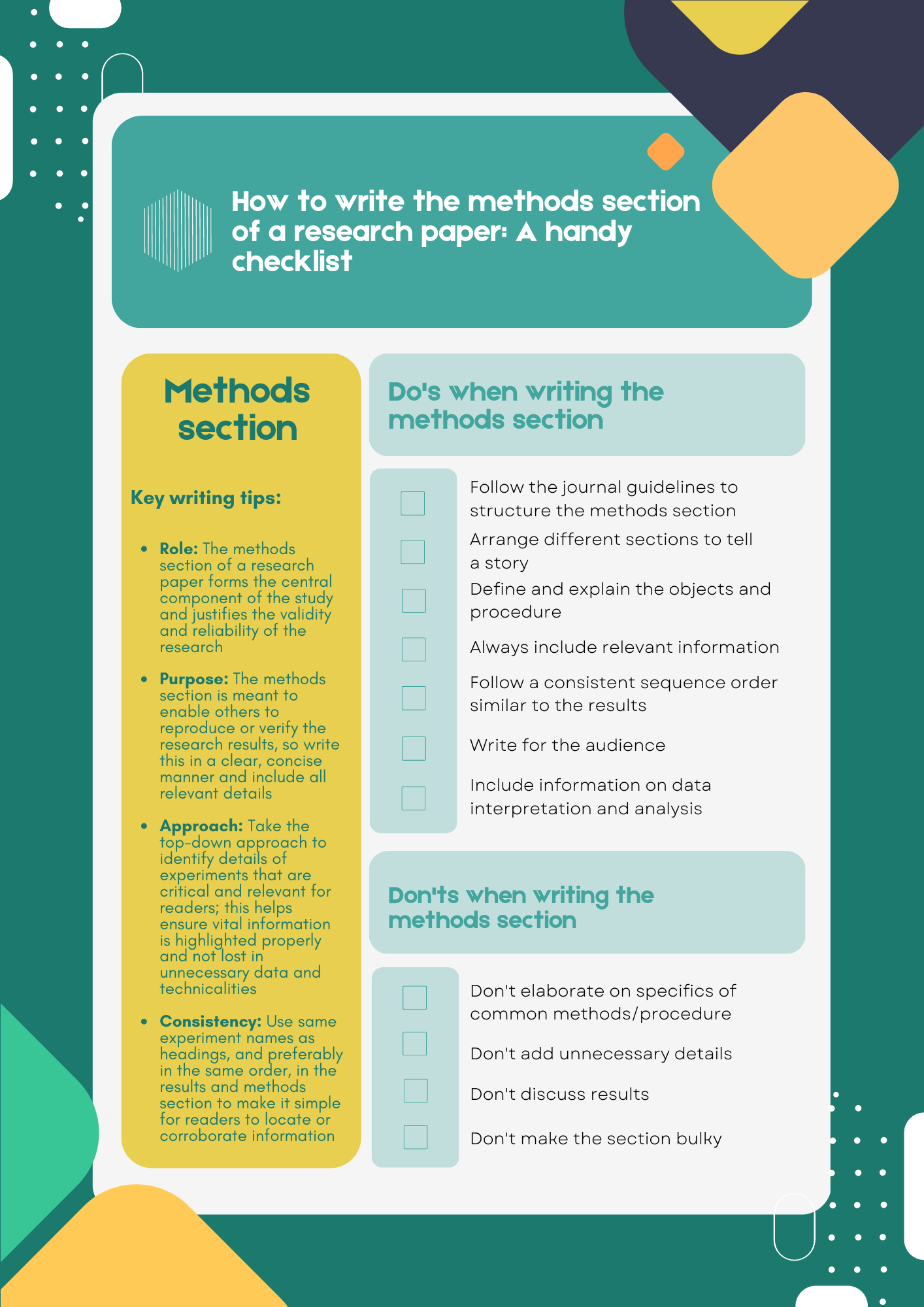

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE: Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE: If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in and of itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. "How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section." Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Blair Lorrie. “Choosing a Methodology.” In Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation , Teaching Writing Series. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2016), pp. 49-72; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Kallet, Richard H. “How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper.” Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004):1229-1232; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Rudestam, Kjell Erik and Rae R. Newton. “The Method Chapter: Describing Your Research Plan.” In Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process . (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015), pp. 87-115; What is Interpretive Research. Institute of Public and International Affairs, University of Utah; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

To locate data and statistics, GO HERE .

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between the application of theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics . Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship. S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Methods and the Methodology

Do not confuse the terms "methods" and "methodology." As Schneider notes, a method refers to the technical steps taken to do research . Descriptions of methods usually include defining and stating why you have chosen specific techniques to investigate a research problem, followed by an outline of the procedures you used to systematically select, gather, and process the data [remember to always save the interpretation of data for the discussion section of your paper].

The methodology refers to a discussion of the underlying reasoning why particular methods were used . This discussion includes describing the theoretical concepts that inform the choice of methods to be applied, placing the choice of methods within the more general nature of academic work, and reviewing its relevance to examining the research problem. The methodology section also includes a thorough review of the methods other scholars have used to study the topic.

Bryman, Alan. "Of Methods and Methodology." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 3 (2008): 159-168; Schneider, Florian. “What's in a Methodology: The Difference between Method, Methodology, and Theory…and How to Get the Balance Right?” PoliticsEastAsia.com. Chinese Department, University of Leiden, Netherlands.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP23720

Published by Nicolas at March 21st, 2024 , Revised On March 12, 2024

The Ultimate Guide To Research Methodology

Research methodology is a crucial aspect of any investigative process, serving as the blueprint for the entire research journey. If you are stuck in the methodology section of your research paper , then this blog will guide you on what is a research methodology, its types and how to successfully conduct one.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Methodology?

Research methodology can be defined as the systematic framework that guides researchers in designing, conducting, and analyzing their investigations. It encompasses a structured set of processes, techniques, and tools employed to gather and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of the research findings.

Research methodology is not confined to a singular approach; rather, it encapsulates a diverse range of methods tailored to the specific requirements of the research objectives.

Here is why Research methodology is important in academic and professional settings.

Facilitating Rigorous Inquiry

Research methodology forms the backbone of rigorous inquiry. It provides a structured approach that aids researchers in formulating precise thesis statements , selecting appropriate methodologies, and executing systematic investigations. This, in turn, enhances the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

Ensuring Reproducibility And Reliability

In both academic and professional contexts, the ability to reproduce research outcomes is paramount. A well-defined research methodology establishes clear procedures, making it possible for others to replicate the study. This not only validates the findings but also contributes to the cumulative nature of knowledge.

Guiding Decision-Making Processes

In professional settings, decisions often hinge on reliable data and insights. Research methodology equips professionals with the tools to gather pertinent information, analyze it rigorously, and derive meaningful conclusions.

This informed decision-making is instrumental in achieving organizational goals and staying ahead in competitive environments.

Contributing To Academic Excellence

For academic researchers, adherence to robust research methodology is a hallmark of excellence. Institutions value research that adheres to high standards of methodology, fostering a culture of academic rigour and intellectual integrity. Furthermore, it prepares students with critical skills applicable beyond academia.

Enhancing Problem-Solving Abilities

Research methodology instills a problem-solving mindset by encouraging researchers to approach challenges systematically. It equips individuals with the skills to dissect complex issues, formulate hypotheses , and devise effective strategies for investigation.

Understanding Research Methodology

In the pursuit of knowledge and discovery, understanding the fundamentals of research methodology is paramount.

Basics Of Research

Research, in its essence, is a systematic and organized process of inquiry aimed at expanding our understanding of a particular subject or phenomenon. It involves the exploration of existing knowledge, the formulation of hypotheses, and the collection and analysis of data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Research is a dynamic and iterative process that contributes to the continuous evolution of knowledge in various disciplines.

Types of Research

Research takes on various forms, each tailored to the nature of the inquiry. Broadly classified, research can be categorized into two main types:

- Quantitative Research: This type involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify patterns, relationships, and statistical significance. It is particularly useful for testing hypotheses and making predictions.

- Qualitative Research: Qualitative research focuses on understanding the depth and details of a phenomenon through non-numerical data. It often involves methods such as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis, providing rich insights into complex issues.

Components Of Research Methodology

To conduct effective research, one must go through the different components of research methodology. These components form the scaffolding that supports the entire research process, ensuring its coherence and validity.

Research Design

Research design serves as the blueprint for the entire research project. It outlines the overall structure and strategy for conducting the study. The three primary types of research design are:

- Exploratory Research: Aimed at gaining insights and familiarity with the topic, often used in the early stages of research.

- Descriptive Research: Involves portraying an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon, answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Explanatory Research: Seeks to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how.’

Data Collection Methods

Choosing the right data collection methods is crucial for obtaining reliable and relevant information. Common methods include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Employed to gather information from a large number of respondents through standardized questions.

- Interviews: In-depth conversations with participants, offering qualitative insights.

- Observation: Systematic watching and recording of behaviour, events, or processes in their natural setting.

Data Analysis Techniques

Once data is collected, analysis becomes imperative to derive meaningful conclusions. Different methodologies exist for quantitative and qualitative data:

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Involves statistical techniques such as descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and regression analysis to interpret numerical data.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Methods like content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory are employed to extract patterns, themes, and meanings from non-numerical data.

The research paper we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Choosing a Research Method

Selecting an appropriate research method is a critical decision in the research process. It determines the approach, tools, and techniques that will be used to answer the research questions.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data, providing a structured and objective approach to understanding and explaining phenomena.

Experimental Research

Experimental research involves manipulating variables to observe the effect on another variable under controlled conditions. It aims to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Key Characteristics:

- Controlled Environment: Experiments are conducted in a controlled setting to minimize external influences.

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different experimental conditions.

- Quantitative Data: Data collected is numerical, allowing for statistical analysis.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies and psychology to test hypotheses and identify causal relationships.

Survey Research

Survey research gathers information from a sample of individuals through standardized questionnaires or interviews. It aims to collect data on opinions, attitudes, and behaviours.

- Structured Instruments: Surveys use structured instruments, such as questionnaires, to collect data.

- Large Sample Size: Surveys often target a large and diverse group of participants.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Responses are quantified for statistical analysis.

Applications: Widely employed in social sciences, marketing, and public opinion research to understand trends and preferences.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research seeks to portray an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon. It focuses on answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Observation and Data Collection: This involves observing and documenting without manipulating variables.

- Objective Description: Aim to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: T his can include both types of data, depending on the research focus.

Applications: Useful in situations where researchers want to understand and describe a phenomenon without altering it, common in social sciences and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research emphasizes exploring and understanding the depth and complexity of phenomena through non-numerical data.

A case study is an in-depth exploration of a particular person, group, event, or situation. It involves detailed, context-rich analysis.

- Rich Data Collection: Uses various data sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents.

- Contextual Understanding: Aims to understand the context and unique characteristics of the case.

- Holistic Approach: Examines the case in its entirety.

Applications: Common in social sciences, psychology, and business to investigate complex and specific instances.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves immersing the researcher in the culture or community being studied to gain a deep understanding of their behaviours, beliefs, and practices.

- Participant Observation: Researchers actively participate in the community or setting.

- Holistic Perspective: Focuses on the interconnectedness of cultural elements.

- Qualitative Data: In-depth narratives and descriptions are central to ethnographic studies.

Applications: Widely used in anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies to explore and document cultural practices.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory aims to develop theories grounded in the data itself. It involves systematic data collection and analysis to construct theories from the ground up.

- Constant Comparison: Data is continually compared and analyzed during the research process.

- Inductive Reasoning: Theories emerge from the data rather than being imposed on it.

- Iterative Process: The research design evolves as the study progresses.

Applications: Commonly applied in sociology, nursing, and management studies to generate theories from empirical data.

Research design is the structural framework that outlines the systematic process and plan for conducting a study. It serves as the blueprint, guiding researchers on how to collect, analyze, and interpret data.

Exploratory, Descriptive, And Explanatory Designs

Exploratory design.

Exploratory research design is employed when a researcher aims to explore a relatively unknown subject or gain insights into a complex phenomenon.

- Flexibility: Allows for flexibility in data collection and analysis.

- Open-Ended Questions: Uses open-ended questions to gather a broad range of information.

- Preliminary Nature: Often used in the initial stages of research to formulate hypotheses.

Applications: Valuable in the early stages of investigation, especially when the researcher seeks a deeper understanding of a subject before formalizing research questions.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research design focuses on portraying an accurate profile of a situation, group, or phenomenon.

- Structured Data Collection: Involves systematic and structured data collection methods.

- Objective Presentation: Aims to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: Can incorporate both types of data, depending on the research objectives.

Applications: Widely used in social sciences, marketing, and educational research to provide detailed and objective descriptions.

Explanatory Design

Explanatory research design aims to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind observed relationships.

- Causal Relationships: Seeks to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Controlled Variables : Often involves controlling certain variables to isolate causal factors.

- Quantitative Analysis: Primarily relies on quantitative data analysis techniques.

Applications: Commonly employed in scientific studies and social sciences to delve into the underlying reasons behind observed patterns.

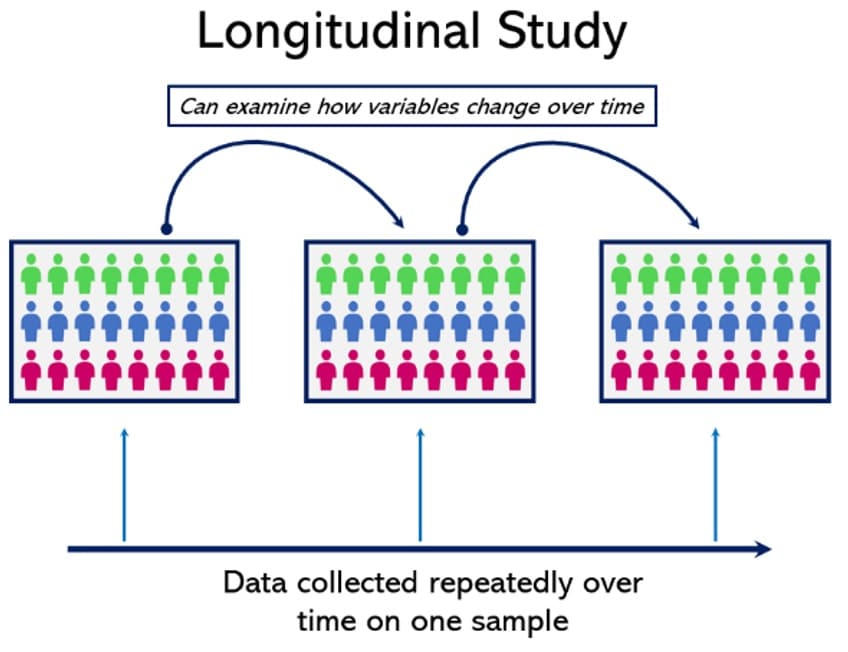

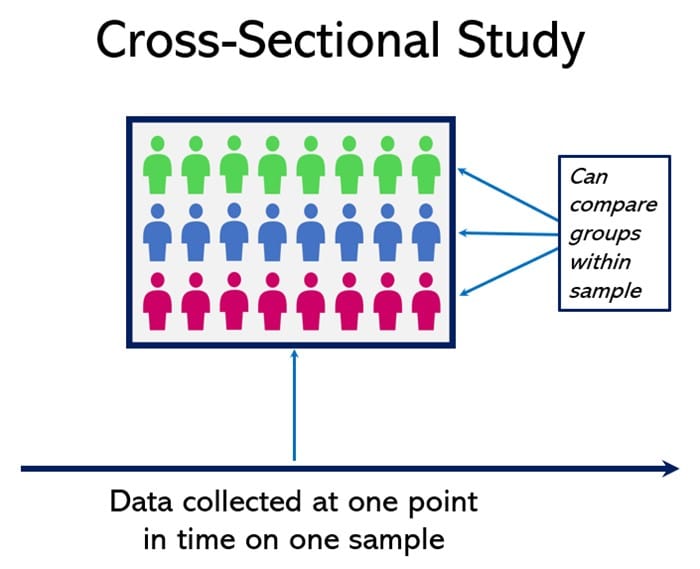

Cross-Sectional Vs. Longitudinal Designs

Cross-sectional design.

Cross-sectional designs collect data from participants at a single point in time.

- Snapshot View: Provides a snapshot of a population at a specific moment.

- Efficiency: More efficient in terms of time and resources.

- Limited Temporal Insights: Offers limited insights into changes over time.

Applications: Suitable for studying characteristics or behaviours that are stable or not expected to change rapidly.

Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal designs involve the collection of data from the same participants over an extended period.

- Temporal Sequence: Allows for the examination of changes over time.

- Causality Assessment: Facilitates the assessment of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Resource-Intensive: Requires more time and resources compared to cross-sectional designs.

Applications: Ideal for studying developmental processes, trends, or the impact of interventions over time.

Experimental Vs Non-experimental Designs

Experimental design.

Experimental designs involve manipulating variables under controlled conditions to observe the effect on another variable.

- Causality Inference: Enables the inference of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Quantitative Data: Primarily involves the collection and analysis of numerical data.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies, psychology, and medical research to establish causal relationships.

Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental designs observe and describe phenomena without manipulating variables.

- Natural Settings: Data is often collected in natural settings without intervention.

- Descriptive or Correlational: Focuses on describing relationships or correlations between variables.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: This can involve either type of data, depending on the research approach.

Applications: Suitable for studying complex phenomena in real-world settings where manipulation may not be ethical or feasible.

Effective data collection is fundamental to the success of any research endeavour.

Designing Effective Surveys

Objective Design:

- Clearly define the research objectives to guide the survey design.

- Craft questions that align with the study’s goals and avoid ambiguity.

Structured Format:

- Use a structured format with standardized questions for consistency.

- Include a mix of closed-ended and open-ended questions for detailed insights.

Pilot Testing:

- Conduct pilot tests to identify and rectify potential issues with survey design.

- Ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of questions.

Sampling Strategy:

- Develop a robust sampling strategy to ensure a representative participant group.

- Consider random sampling or stratified sampling based on the research goals.

Conducting Interviews

Establishing Rapport:

- Build rapport with participants to create a comfortable and open environment.

- Clearly communicate the purpose of the interview and the value of participants’ input.

Open-Ended Questions:

- Frame open-ended questions to encourage detailed responses.

- Allow participants to express their thoughts and perspectives freely.

Active Listening:

- Practice active listening to understand areas and gather rich data.

- Avoid interrupting and maintain a non-judgmental stance during the interview.

Ethical Considerations:

- Obtain informed consent and assure participants of confidentiality.

- Be transparent about the study’s purpose and potential implications.

Observation

1. participant observation.

Immersive Participation:

- Actively immerse yourself in the setting or group being observed.

- Develop a deep understanding of behaviours, interactions, and context.

Field Notes:

- Maintain detailed and reflective field notes during observations.

- Document observed patterns, unexpected events, and participant reactions.

Ethical Awareness:

- Be conscious of ethical considerations, ensuring respect for participants.

- Balance the role of observer and participant to minimize bias.

2. Non-participant Observation

Objective Observation:

- Maintain a more detached and objective stance during non-participant observation.

- Focus on recording behaviours, events, and patterns without direct involvement.

Data Reliability:

- Enhance the reliability of data by reducing observer bias.

- Develop clear observation protocols and guidelines.

Contextual Understanding:

- Strive for a thorough understanding of the observed context.

- Consider combining non-participant observation with other methods for triangulation.

Archival Research

1. using existing data.

Identifying Relevant Archives:

- Locate and access archives relevant to the research topic.

- Collaborate with institutions or repositories holding valuable data.

Data Verification:

- Verify the accuracy and reliability of archived data.

- Cross-reference with other sources to ensure data integrity.

Ethical Use:

- Adhere to ethical guidelines when using existing data.

- Respect copyright and intellectual property rights.

2. Challenges and Considerations

Incomplete or Inaccurate Archives:

- Address the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate archival records.

- Acknowledge limitations and uncertainties in the data.

Temporal Bias:

- Recognize potential temporal biases in archived data.

- Consider the historical context and changes that may impact interpretation.

Access Limitations:

- Address potential limitations in accessing certain archives.

- Seek alternative sources or collaborate with institutions to overcome barriers.

Common Challenges in Research Methodology

Conducting research is a complex and dynamic process, often accompanied by a myriad of challenges. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure the reliability and validity of research findings.

Sampling Issues

Sampling bias:.

- The presence of sampling bias can lead to an unrepresentative sample, affecting the generalizability of findings.

- Employ random sampling methods and ensure the inclusion of diverse participants to reduce bias.

Sample Size Determination:

- Determining an appropriate sample size is a delicate balance. Too small a sample may lack statistical power, while an excessively large sample may strain resources.

- Conduct a power analysis to determine the optimal sample size based on the research objectives and expected effect size.

Data Quality And Validity

Measurement error:.

- Inaccuracies in measurement tools or data collection methods can introduce measurement errors, impacting the validity of results.

- Pilot test instruments, calibrate equipment, and use standardized measures to enhance the reliability of data.

Construct Validity:

- Ensuring that the chosen measures accurately capture the intended constructs is a persistent challenge.

- Use established measurement instruments and employ multiple measures to assess the same construct for triangulation.

Time And Resource Constraints

Timeline pressures:.

- Limited timeframes can compromise the depth and thoroughness of the research process.

- Develop a realistic timeline, prioritize tasks, and communicate expectations with stakeholders to manage time constraints effectively.

Resource Availability:

- Inadequate resources, whether financial or human, can impede the execution of research activities.

- Seek external funding, collaborate with other researchers, and explore alternative methods that require fewer resources.

Managing Bias in Research

Selection bias:.

- Selecting participants in a way that systematically skews the sample can introduce selection bias.

- Employ randomization techniques, use stratified sampling, and transparently report participant recruitment methods.

Confirmation Bias:

- Researchers may unintentionally favour information that confirms their preconceived beliefs or hypotheses.

- Adopt a systematic and open-minded approach, use blinded study designs, and engage in peer review to mitigate confirmation bias.

Tips On How To Write A Research Methodology

Conducting successful research relies not only on the application of sound methodologies but also on strategic planning and effective collaboration. Here are some tips to enhance the success of your research methodology:

Tip 1. Clear Research Objectives

Well-defined research objectives guide the entire research process. Clearly articulate the purpose of your study, outlining specific research questions or hypotheses.

Tip 2. Comprehensive Literature Review

A thorough literature review provides a foundation for understanding existing knowledge and identifying gaps. Invest time in reviewing relevant literature to inform your research design and methodology.

Tip 3. Detailed Research Plan

A detailed plan serves as a roadmap, ensuring all aspects of the research are systematically addressed. Develop a detailed research plan outlining timelines, milestones, and tasks.

Tip 4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical practices are fundamental to maintaining the integrity of research. Address ethical considerations early, obtain necessary approvals, and ensure participant rights are safeguarded.

Tip 5. Stay Updated On Methodologies

Research methodologies evolve, and staying updated is essential for employing the most effective techniques. Engage in continuous learning by attending workshops, conferences, and reading recent publications.

Tip 6. Adaptability In Methods

Unforeseen challenges may arise during research, necessitating adaptability in methods. Be flexible and willing to modify your approach when needed, ensuring the integrity of the study.

Tip 7. Iterative Approach

Research is often an iterative process, and refining methods based on ongoing findings enhance the study’s robustness. Regularly review and refine your research design and methods as the study progresses.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the research methodology.

Research methodology is the systematic process of planning, executing, and evaluating scientific investigation. It encompasses the techniques, tools, and procedures used to collect, analyze, and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of research findings.

What are the methodologies in research?

Research methodologies include qualitative and quantitative approaches. Qualitative methods involve in-depth exploration of non-numerical data, while quantitative methods use statistical analysis to examine numerical data. Mixed methods combine both approaches for a comprehensive understanding of research questions.

How to write research methodology?

To write a research methodology, clearly outline the study’s design, data collection, and analysis procedures. Specify research tools, participants, and sampling methods. Justify choices and discuss limitations. Ensure clarity, coherence, and alignment with research objectives for a robust methodology section.

How to write the methodology section of a research paper?

In the methodology section of a research paper, describe the study’s design, data collection, and analysis methods. Detail procedures, tools, participants, and sampling. Justify choices, address ethical considerations, and explain how the methodology aligns with research objectives, ensuring clarity and rigour.

What is mixed research methodology?

Mixed research methodology combines both qualitative and quantitative research approaches within a single study. This approach aims to enhance the details and depth of research findings by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem or question.

You May Also Like

In Canada, scholarships are generally not taxable if they are for education in a qualifying program. Consult tax regulations or a professional for accurate information.

To cite a TED Talk in APA style, include speaker’s name, publication year, talk title, “TED Conferences,” and URL for clarity and accuracy.

Do you require captivating and feasible research subjects in the area of nursing and medicine? If so, then your search […]

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources.

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Topic Guides

- Research Methods Guide

- Research Design & Method

Research Methods Guide: Research Design & Method

- Introduction

- Survey Research

- Interview Research

- Data Analysis

- Resources & Consultation

Tutorial Videos: Research Design & Method

Research Methods (sociology-focused)

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Methods (intro)

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Methods (advanced)

FAQ: Research Design & Method

What is the difference between Research Design and Research Method?

Research design is a plan to answer your research question. A research method is a strategy used to implement that plan. Research design and methods are different but closely related, because good research design ensures that the data you obtain will help you answer your research question more effectively.

Which research method should I choose ?

It depends on your research goal. It depends on what subjects (and who) you want to study. Let's say you are interested in studying what makes people happy, or why some students are more conscious about recycling on campus. To answer these questions, you need to make a decision about how to collect your data. Most frequently used methods include:

- Observation / Participant Observation

- Focus Groups

- Experiments

- Secondary Data Analysis / Archival Study

- Mixed Methods (combination of some of the above)

One particular method could be better suited to your research goal than others, because the data you collect from different methods will be different in quality and quantity. For instance, surveys are usually designed to produce relatively short answers, rather than the extensive responses expected in qualitative interviews.

What other factors should I consider when choosing one method over another?

Time for data collection and analysis is something you want to consider. An observation or interview method, so-called qualitative approach, helps you collect richer information, but it takes time. Using a survey helps you collect more data quickly, yet it may lack details. So, you will need to consider the time you have for research and the balance between strengths and weaknesses associated with each method (e.g., qualitative vs. quantitative).

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Survey Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 10:42 AM

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

Writing the research paper.

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

Before Writing the Paper

Methods, thesis and hypothesis, clarity, precision and academic expression, format your paper, typical problems, a few suggestions, avoid plagiarism.

- Presenting the Research Paper

Find a topic.

- Try to find a subject that really interests you.

- While you explore the topic, narrow or broaden your target and focus on something that gives the most promising results.

- Don't choose a huge subject if you have to write a 3 page long paper, and broaden your topic sufficiently if you have to submit at least 25 pages.

- Consult your class instructor (and your classmates) about the topic.

Explore the topic.

- Find primary and secondary sources in the library.

- Read and critically analyse them.

- Take notes.

- Compile surveys, collect data, gather materials for quantitative analysis (if these are good methods to investigate the topic more deeply).

- Come up with new ideas about the topic. Try to formulate your ideas in a few sentences.

- Review your notes and other materials and enrich the outline.

- Try to estimate how long the individual parts will be.

- Do others understand what you want to say?

- Do they accept it as new knowledge or relevant and important for a paper?

- Do they agree that your thoughts will result in a successful paper?

- Qualitative: gives answers on questions (how, why, when, who, what, etc.) by investigating an issue

- Quantitative:requires data and the analysis of data as well

- the essence, the point of the research paper in one or two sentences.

- a statement that can be proved or disproved.

- Be specific.

- Avoid ambiguity.

- Use predominantly the active voice, not the passive.

- Deal with one issue in one paragraph.

- Be accurate.

- Double-check your data, references, citations and statements.

Academic Expression

- Don't use familiar style or colloquial/slang expressions.

- Write in full sentences.

- Check the meaning of the words if you don't know exactly what they mean.

- Avoid metaphors.

- Almost the rough content of every paragraph.

- The order of the various topics in your paper.

- On the basis of the outline, start writing a part by planning the content, and then write it down.

- Put a visible mark (which you will later delete) where you need to quote a source, and write in the citation when you finish writing that part or a bigger part.

- Does the text make sense?

- Could you explain what you wanted?

- Did you write good sentences?

- Is there something missing?

- Check the spelling.

- Complete the citations, bring them in standard format.

Use the guidelines that your instructor requires (MLA, Chicago, APA, Turabian, etc.).

- Adjust margins, spacing, paragraph indentation, place of page numbers, etc.

- Standardize the bibliography or footnotes according to the guidelines.

- EndNote and EndNote Basic by UCLA Library Last Updated Jul 3, 2024 1921 views this year

- Zotero by UCLA Library Last Updated Jul 22, 2024 1232 views this year

(Based on English Composition 2 from Illinois Valley Community College):

- Weak organization

- Poor support and development of ideas

- Weak use of secondary sources

- Excessive errors

- Stylistic weakness

When collecting materials, selecting research topic, and writing the paper:

- Be systematic and organized (e.g. keep your bibliography neat and organized; write your notes in a neat way, so that you can find them later on.

- Use your critical thinking ability when you read.

- Write down your thoughts (so that you can reconstruct them later).

- Stop when you have a really good idea and think about whether you could enlarge it to a whole research paper. If yes, take much longer notes.

- When you write down a quotation or summarize somebody else's thoughts in your notes or in the paper, cite the source (i.e. write down the author, title, publication place, year, page number).

- If you quote or summarize a thought from the internet, cite the internet source.

- Write an outline that is detailed enough to remind you about the content.

- Read your paper for yourself or, preferably, somebody else.

- When you finish writing, check the spelling;

- Use the citation form (MLA, Chicago, or other) that your instructor requires and use it everywhere.

Plagiarism : somebody else's words or ideas presented without citation by an author

- Cite your source every time when you quote a part of somebody's work.

- Cite your source every time when you summarize a thought from somebody's work.

- Cite your source every time when you use a source (quote or summarize) from the Internet.

Consult the Citing Sources research guide for further details.

- << Previous: Writing a Research Proposal

- Next: Presenting the Research Paper >>

- Last Updated: Jul 24, 2024 1:23 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The methods section of a research paper provides the information by which a study’s validity is judged. The method section answers two main questions: 1) How was the data collected or generated? 2) How was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and written in the past tense.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you choose affects the results and, by extension, how you likely interpreted those results.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and it misappropriates interpretations of findings .

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. Your methodology section of your paper should make clear the reasons why you chose a particular method or procedure .

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The research method must be appropriate to the objectives of the study . For example, be sure you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring . For any problems that did arise, you must describe the ways in which their impact was minimized or why these problems do not affect the findings in any way that impacts your interpretation of the data.

- Often in social science research, it is useful for other researchers to adapt or replicate your methodology. Therefore, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow others to use or replicate the study . This information is particularly important when a new method had been developed or an innovative use of an existing method has been utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article . Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The empirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences. This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation .

- The interpretative group is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . This research method allows you to recognize your connection to the subject under study. Because the interpretative group focuses more on subjective knowledge, it requires careful interpretation of variables.

II. Content

An effectively written methodology section should: