John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

John Bowlby (1907 – 1990) was a psychoanalyst (like Freud) and believed that mental health and behavioral problems could be attributed to early childhood.

Key Takeaways

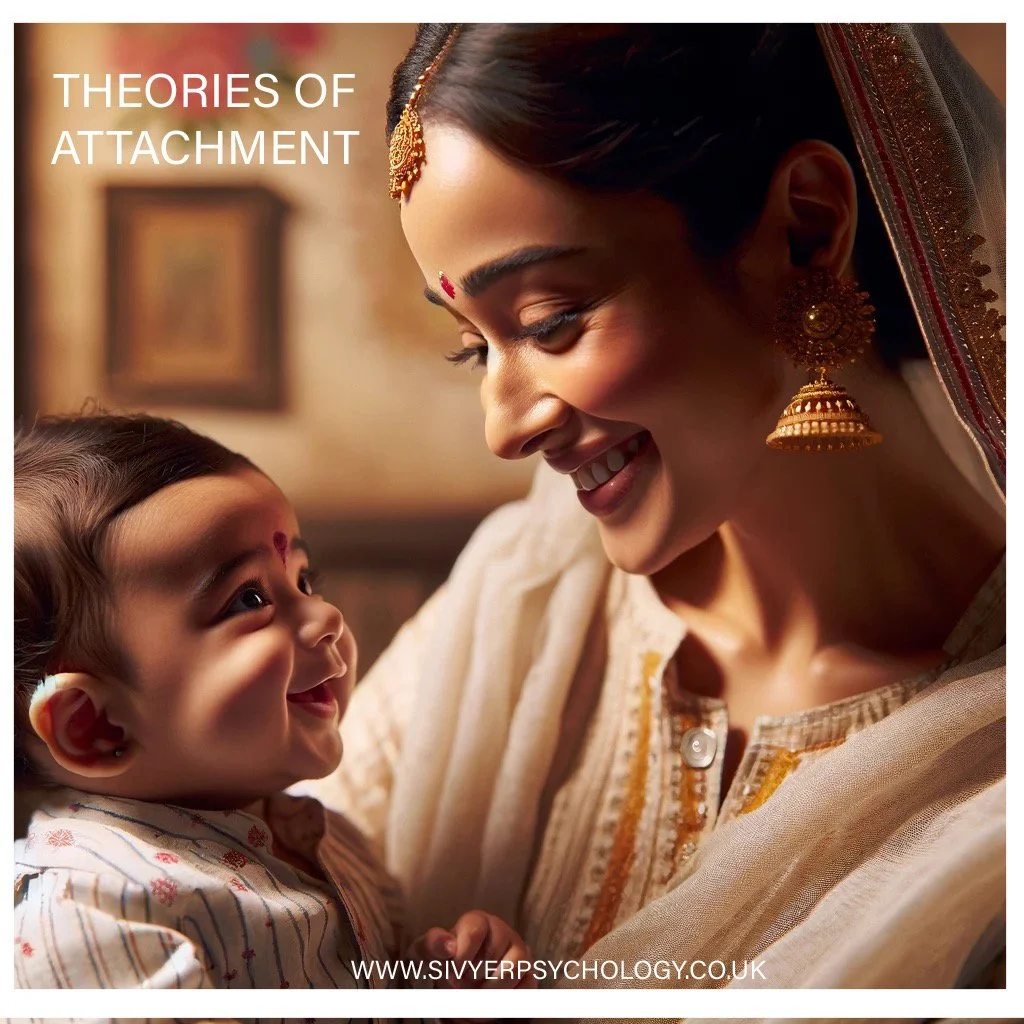

- Bowlby’s evolutionary theory of attachment suggests that children come into the world biologically pre-programmed to form attachments with others, because this will help them to survive.

- Bowlby argued that a child forms many attachments, but one of these is qualitatively different. This is what he called primary attachment, monotropy.

- Bowlby suggests that there is a critical period for developing attachment (2.5 years). If an attachment has not developed during this time period, then it may well not happen at all. Bowlby later proposed a sensitive period of up to 5 years.

- Bowlby’s maternal deprivation hypothesis suggests that continual attachment disruption between the infant and primary caregiver could result in long-term cognitive, social, and emotional difficulties for that infant.

- According to Bowlby, an internal working model is a cognitive framework comprising mental representations for understanding the world, self, and others, and is based on the relationship with a primary caregiver.

- It becomes a prototype for all future social relationships and allows individuals to predict, control, and manipulate interactions with others.

Evolutionary Theory of Attachment

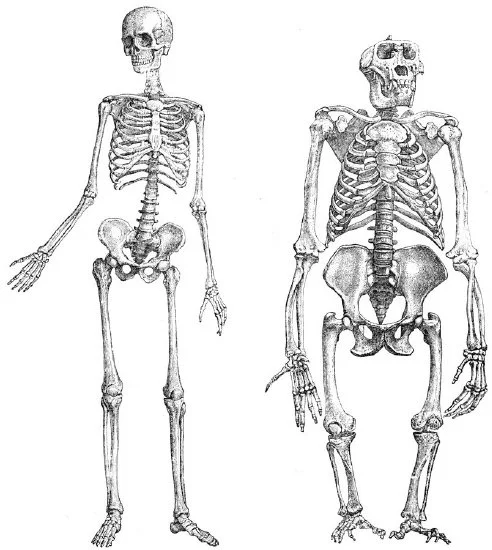

Bowlby (1969, 1988) was greatly influenced by ethological theory, but especially by Lorenz’s (1935) study of imprinting . Lorenz showed that attachment was innate (in young ducklings) and therefore had a survival value.

During the evolution of the human species, it would have been the babies who stayed close to their mothers that would have survived to have children of their own. Bowlby hypothesized that both infants and mothers had evolved a biological need to stay in contact with each other.

Bowlby (1969) believed that attachment behaviors (such as proximity seeking) are instinctive and will be activated by any conditions that seem to threaten the achievement of proximity, such as separation, insecurity, and fear.

Bowlby also postulated that the fear of strangers represents an important survival mechanism, built-in by nature.

Babies are born with the tendency to display certain innate behaviors (called social releases), which help ensure proximity and contact with the mother or attachment figure (e.g., crying, smiling, crawling, etc.) – these are species-specific behaviors.

These attachment behaviors initially function like fixed action patterns and share the same function. The infant produces innate ‘social releaser’ behaviors such as crying and smiling that stimulate caregiving from adults.

The determinant of attachment is not food but care and responsiveness.

Bowlby’s monotropic theory

A child has an innate (i.e., inborn) need to attach to one main attachment figure (i.e., monotropy).

Bowlby’s monotropic theory of attachment suggests attachment is important for a child’s survival.

Attachment behaviors in both babies and their caregivers have evolved through natural selection. This means infants are biologically programmed with innate behaviors that ensure that attachment occurs.

Although Bowlby did not rule out the possibility of other attachment figures for a child, he did believe that there should be a primary bond which was much more important than any other (usually the mother).

Other attachments may develop in a hierarchy below this. An infant may therefore have a primary monotropy attachment to its mother, and below her, the hierarchy of attachments may include its father, siblings, grandparents, etc.

Bowlby believes that this attachment is qualitatively different from any subsequent attachments. Bowlby argues that the relationship with the mother is somehow different altogether from other relationships.

The child behaves in ways that elicit contact or proximity to the caregiver. When a child experiences heightened arousal, he/she signals to their caregiver.

Crying, smiling, and locomotion are examples of these signaling behaviors. Instinctively, caregivers respond to their children’s behavior, creating a reciprocal pattern of interaction.

Critical Period

A child should receive the continuous care of this single most important attachment figure for approximately the first two years of life.

Bowlby (1951) claimed that mothering is almost useless if delayed until after two and a half to three years and, for most children, if delayed till after 12 months, i.e., there is a critical period.

If the attachment figure is broken or disrupted during the critical two-year period, the child will suffer irreversible long-term consequences of this maternal deprivation. This risk continues until the age of five.

Bowlby used the term maternal deprivation to refer to the separation or loss of the mother as well as the failure to develop an attachment.

The underlying assumption of Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis is that continual disruption of the attachment between infant and primary caregiver (i.e., mother) could result in long-term cognitive, social, and emotional difficulties for that infant.

The implications of this are vast – if this is true, should the primary caregiver leave their child in daycare, while they continue to work?

Maternal Deprivation

Bowlby’s maternal deprivation hypothesis suggests that continual attachment disruption between the infant and primary caregiver (i.e., mother) could result in long-term cognitive, social, and emotional difficulties for that infant.

Bowlby (1988) suggested that the nature of monotropy (attachment conceptualized as being a vital and close bond with just one attachment figure) meant that a failure to initiate or a breakdown of the maternal attachment would lead to serious negative consequences, possibly including affectionless psychopathy.

Bowlby’s theory of monotropy led to the formulation of his maternal deprivation hypothesis.

John Bowlby (1944) believed that the infant’s and mother’s relationship during the first five years of life was crucial to socialization.

According to Bowlby, if separation from the primary caregiver occurs during the critical period and there is no adequate substitute emotional care, the child will suffer from deprivation.

This will lead to irreversible long-term consequences in the child’s intellectual, social, and emotional development.

Bowlby initially believed the effects to be permanent and irreversible:

- delinquency,

- reduced intelligence,

- increased aggression,

- depression,

- affectionless psychopathy

Bowlby also argued that the lack of emotional care could lead to affectionless psychopathy,

Affectionless psychopathy is characterized by a lack of concern for others, a lack of guilt, and the inability to form meaningful relationships.

Such individuals act on impulse with little regard for the consequences of their actions. For example, showing no guilt for antisocial behavior.

The prolonged deprivation of the young child of maternal care may have grave and far-reaching effects on his character and so on the whole of his future life (Bowlby, 1952, p. 46).

Bowlby believed that disrupting this primary relationship could lead to a higher incidence of juvenile delinquency, emotional difficulties, and antisocial behavior. To test his hypothesis, he studied 44 adolescent juvenile delinquents in a child guidance clinic.

Bowlby 44 Thieves

To investigate the long-term effects of maternal deprivation on people to see whether delinquents have suffered deprivation.

According to the Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis, breaking the maternal bond with the child during their early life stages is likely to affect intellectual, social, and emotional development seriously.

Between 1936 and 1939, an opportunity sample of 88 children was selected from the clinic where Bowlby worked. Of these, 44 were juvenile thieves (31 boys and 13 girls) who had been referred to him because of their stealing.

Bowlby selected another group of 44 children (34 boys and 10 girls) to act as ‘controls (individuals referred to the clinic because of emotional problems but not yet committed any crimes).

On arrival at the clinic, each child had their IQ tested by a psychologist who assessed their emotional attitudes toward the tests. The two groups were matched for age and IQ.

The children and their parents were interviewed to record details of the child’s early life (e.g., periods of separation, diagnosing affectionless psychopathy) by a psychiatrist (Bowlby), a psychologist, and a social worker. The psychiatrist, psychologist, and social worker made separate reports.

Bowlby found that 14 children from the thief group were identified as affectionless psychopaths (they were unable to care about or feel affection for others); 12 had experienced prolonged separation of more than six months from their mothers in their first two years of life.

In contrast, only 5 of the 30 children not classified as affectionless psychopaths had experienced separations.

Out of the 44 children in the control group, only two experienced prolonged separations, and none were affectionless psychopaths.

The results support the maternal deprivation hypothesis as they show that most of the children diagnosed as affectionless psychopaths (12 out of 14) had experienced prolonged separation from their primary caregivers during the critical period, as the hypothesis predicts

Bowlby concluded that maternal deprivation in the child’s early life caused permanent emotional damage.

He diagnosed this as a condition and called it Affectionless Psychopathy. According to Bowlby, this condition involves a lack of emotional development, characterized by a lack of concern for others, a lack of guilt, and an inability to form meaningful and lasting relationships.

Bowlby directly observed parental separation’s harm in evacuating children from bombing during WWII, strengthening his hospital research indicating it profoundly impacts children’s emotional and behavioral development.

Limitations

The supporting evidence that Bowlby (1944) provided was in the form of clinical interviews of, and retrospective data on, those who had and had not been separated from their primary caregiver.

This meant that Bowlby asked the participants to look back and recall separations. These memories may not be accurate.

A criticism of the 44 thieves study was that it concluded affectionless psychopathy was caused by maternal deprivation. This is correlational data and only shows a relationship between these two variables. It cannot show a cause-and-effect relationship between separation from the mother and the development of affectionless psychopathy.

Other factors could have been involved, such as the reason for the separation, the role of the father, and the child’s temperament. Thus, as Rutter (1972) pointed out, Bowlby’s conclusions were flawed, mixing up cause and effect with correlation.

Many of the 44 thieves in Bowlby’s study had been moved around a lot during childhood, and had probably never formed an attachment. This suggested that they were suffering from privation, rather than deprivation, which Rutter (1972) suggested was far more deleterious to the children. This led to a very important study on the long-term effects of privation, carried out by Hodges and Tizard (1989).

The study was vulnerable to researcher bias. Bowlby conducted the psychiatric assessments himself and made the diagnosis of Affectionless Psychopathy. He knew whether the children were in the ‘theft group’ or the control group. Consequently, his findings may have been unconsciously influenced by his own expectations. This potentially undermines their validity.

Bowlby struggled to apply his new maladaptation model to retrospective research on adolescents with conduct problems, as such studies prejudice outcomes by selecting for problems and then looking backward.

Cautious of this, in 1950, Bowlby, Robertson, and new researcher Mary Ainsworth (1956) began a forward-looking “follow-up study” on whether preschoolers who were hospitalized long-term subsequently developed conduct issues.

Assessing 60 such children aged 6-13 and controls, contrary to maternal deprivation hypotheses, they found more emotional apathy, withdrawal, and poor control than criminality.

So, while early prolonged separation impacted some children’s later adjustment, outcomes proved far more varied than Bowlby’s theory initially predicted. The improved prospective methodology highlighted limitations in Bowlby’s previous retrospective approaches.

In the conclusions of the paper Bowlby admitted that his theory regarding the development of conduct problems may be wrong:

It is clear that some of the workers, including the present senior author, in their desire to call attention to dangers which can often be avoided have on occasion overstated their case. In particular, statements implying that children who are brought up in institutions or who suffer other forms of serious privation and deprivation in early life commonly develop psychopathic or affectionless characters (e.g., Bowlby, 1944) are seen to be mistaken. (Bowlby et al., 1956, p. 240)

Short-Term Separation

When WWII ended in 1945, Bowlby had to choose between completing child psychoanalysis training or researching parental separation’s impact on children. He chose the latter, joining colleagues at London’s Tavistock Clinic.

Robertson and Bowlby (1952) believe that short-term separation from an attachment figure leads to distress.

John Bowlby spent two years working alongside a social worker, James Robertson (1952), who observed that children experienced intense distress when separated from their mothers. Even when other caregivers fed such children, this did not diminish the child’s anxiety.

They found three progressive stages of distress:

- Protest : The child cries, screams, and protests angrily when the parent leaves. They will try to cling to their parents to stop them from leaving. Protest could last from a few hours to several days.

- Despair : The child’s protesting gradually stops, and they appear calmer, although still upset. The child refuses others’ attempts for comfort and often seems withdrawn and uninterested in anything. In the despair stage, children become increasingly withdrawn and hopeless.

- Detachment : If separation continues, the child will engage with other people again. All emotions are suppressed, and children live moment-to-moment by repressing feelings for their mother. On the surface, children were seen to be happy and content, but when the mother visited, they frequently ignored her and hardly cried when she left. If this state continues, children become so withdrawn as to seek no mothering at all – a sign of major psychological trauma.

Controversy arose between Bowlby and Robertson regarding the stages of separation, particularly the third stage, which Robertson termed denial, but Bowlby called detachment.

However, both powerfully influenced attitudes and practices around keeping mothers and children together. This led to advocacy for allowing parental presence and major reforms in hospital policies.

A Two-Year-Old Goes to Hospital

Though doctors saw the despair phase as adjustment, Bowlby felt it showed distress’s harm.

To demonstrate this, Robertson filmed two-year-old Laura’s distress when hospitalized for eight days for minor surgery in “ A Two-Year-Old Goes to Hospital ” (1952).

Time series photography showed the stages through which a small child, Laura, passed during her 8-day admission for umbilical hernia repair. The film graphically depicted Laura’s behavior while separated from her mother for a period of time in strange circumstances” (Alsop-Shields & Mohay, 2001).

Laura cries out for her mother from admission onward, pleading in anguish to go home when visited the second day. As the week progresses, her initial constant distress gives way to listlessness and detachment during the parents’ increasingly ambivalent visits.

However, when approached by hospital staff, Laura startles out of her trance to suddenly burst into tears and fruitlessly call for her mother once more.

The raw behaviors captured on film revealed the three-phase separation response of protest, despair, and detachment observed in Bowlby and Robertson’s prior research.

Laura’s suffering starkly contradicts expectations of childrens’ ready hospital adjustment, instead demonstrating their deep distress from both physical separation and the hospital environment itself.

These findings contradicted the dominant behavioral theory of attachment (Dollard and Miller, 1950), which was shown to underestimate the child’s bond with their mother. The behavioral theory of attachment states that the child becomes attached to the mother because she feeds the infant.

Implications for nursing include the development of family-centered care models keeping parents integral to a child’s hospital care in order to minimize trauma, principles now widely implemented as a result of this pioneering work on attachment.

Internal Working Model

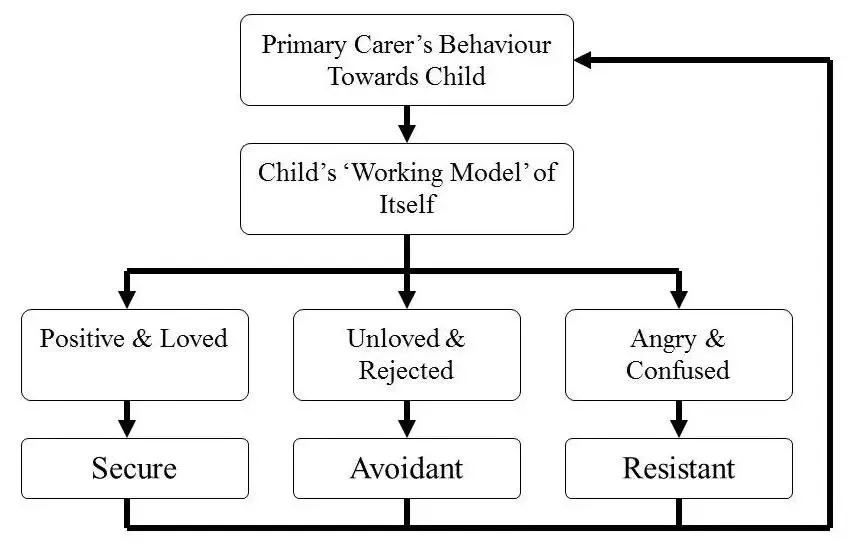

The child’s attachment relationship with their primary caregiver leads to the development of an internal working model (Bowlby, 1969).

This internal working model is a cognitive framework comprising mental representations for understanding the world, self, and others.

The social and emotional responses of the primary caregiver provide the infant with information about the world and other people, and also how they view themselves as individuals.

For example, the extent to which an individual perceives himself/herself as worthy of love and care, and information regarding the availability and reliability of others (Bowlby, 1969).

Bowlby referred to this knowledge as an internal working model (IWM), which begins as a mental and emotional representation of the infant’s first attachment relationship and forms the basis of an individual’s attachment style.

A person’s interaction with others is guided by memories and expectations from their internal model which influence and help evaluate their contact with others (Bretherton & Munholland, 1999).

Working models also comprise cognitions of how to behave and regulate affect when a person’s attachment behavioral system is activated, and notions regarding the availability of attachment figures when called upon.

Bowlby (1969) suggested that the first five years of life were crucial to developing the IWM, although he viewed this as more of a sensitive period rather than a critical one.

Around the age of three, these seem to become part of a child’s personality and thus affect their understanding of the world and future interactions with others (Schore, 2000).

According to Bowlby (1969), the primary caregiver acts as a prototype for future relationships via the internal working model.

There are three main features of the internal working model: (1) a model of others as being trustworthy, (2) a model of the self as valuable, and (3) a model of the self as effective when interacting with others.

It is this mental representation that guides future social and emotional behavior as the child’s internal working model guides their responsiveness to others in general.

The concept of an internal model can be used to show how prior experience is retained over time and to guide perceptions of the social world and future interactions with others.

Early models are typically reinforced via interactions with others over time, and become strengthened and resistant to change, operating mostly at an unconscious level of awareness.

Although working models are generally stable over time they are not impervious to change and as such remain open to modification and revision. This change could occur due to new experiences with attachment figures or through a reconceptualization of past experiences.

Although Bowlby (1969, 1988) believed attachment to be monotropic, he did acknowledge that rather than being a bond with one person, multiple attachments can occur arranged in the form of a hierarchy.

A person can have many internal models, each tied to different relationships and different memory systems, such as semantic and episodic (Bowlby, 1980).

Collins and Read (1994) suggest a hierarchical model of attachment representations whereby general attachment styles and working models appear on the highest level, while relationship-specific models appear on the lowest level.

General models of attachment are thought to originate from early relationships during childhood, and are carried forward to adulthood where they shape perception and behavior in close relationships.

Attachment & Loss Trilogy

The attachment books trilogy developed key concepts regarding attachment, separation distress, loss responses, and clinical implications over the course of the three volumes.

Attachment (1969/1982)

- Provided evidence for the importance of early parent-child relationships.

- Analyzed the systemic and “goal-corrected” nature of behavior.

- Introduced the concept of an “environment of adaptedness” that organisms inherit a potential to develop systems suited for.

- Discussed how attachment behaviors in infants are components of an attachment system designed to achieve security.

- Explained how attachment behaviors change via feedback from caregivers, becoming oriented toward discriminated figures.

- Posited attachment as a foundational system for survival that interacts with other systems like exploration.

Separation (1973)

- Focused on the negative impacts of separation from attachment figures.

- Outlined phases of separation responses in infants and children.

- Analyzed short- and long-term pathological effects of loss or deprivation.

- Studied how mourning progresses in relation to attachment bonds.

- Linked separation distress and avoidance to later issues of delinquency.

Loss (1980)

- Explored the concept of “loss” in relation to attachment theory.

- Proposed stages of the mourning process.

- Studied outcomes following the loss of an attachment figure.

- Examined detachment and defense processes resulting from loss.

- Applied attachment theory understanding to treatment approaches.

Critical Evaluation

Implications for children’s nursing.

- During Robertson and Bowlby’s research, the British government established a parliamentary committee investigating children’s hospital conditions. This resulted in the 1959 Platt Report, containing 55 recommendations, including allowing parental presence and provisions for their accommodation and children’s education/recreation (Alsop-Shields & Mohay, 2001).

- Robertson also specifically critiqued task-oriented nursing and childcare institutions (Robertson, 1955, 1968, 1970) as emotionally neglectful. He and Bowlby suggested dysfunctional families be kept together but supported (Robertson & Bowlby, 1952) – principles now accepted but decades ahead of their time.

- Robertson and Bowlby’s work has greatly influenced the development of family-centered pediatric nursing models like partnership-in-care and family-centered care in the 1990s. By planning care around the whole family unit rather than just the hospitalized child, and involving parents closely in care, these models aim to reduce emotional trauma for children.

Bifulco et al. (1992) support the maternal deprivation hypothesis. They studied 250 women who had lost mothers, through separation or death, before they were 17.

They found that the loss of their mother through separation or death doubles the risk of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult women. The rate of depression was the highest in women whose mothers had died before the child reached 6 years.

Mary Ainsworth’s (1971, 1978) Strange Situation study provides evidence for the existence of the internal working model. A secure child will develop a positive internal working model because it has received sensitive, emotional care from its primary attachment figure.

An insecure-avoidant child will develop an internal working model in which it sees itself as unworthy because its primary attachment figure has reacted negatively to it during the sensitive period for attachment formation.

Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation is supported by Harlow’s (1958) research with monkeys . Harlow showed that monkeys reared in isolation from their mother suffered emotional and social problems in older age. The monkey’s never formed an attachment (privation) and, as such grew up to be aggressive and had problems interacting with other monkeys.

Konrad Lorenz (1935) supports Bowlby’s maternal deprivation hypothesis as the attachment process of imprinting is an innate process.

Bowlby’s (1944, 1956) ideas had a significant influence on the way researchers thought about attachment, and much of the discussion of his theory has focused on his belief in monotropy.

Although Bowlby may not dispute that young children form multiple attachments, he still contends that the attachment to the mother is unique in that it is the first to appear and remains the strongest. However, the evidence seems to suggest otherwise on both of these counts.

- Schaffer & Emerson (1964) noted that specific attachments started at about eight months, and very shortly thereafter, the infants became attached to other people. By 18 months, very few (13%) were attached to only one person; some had five or more attachments.

- Rutter (1972) points out that several indicators of attachment (such as protest or distress when an attached person leaves) have been shown for various attachment figures – fathers, siblings, peers, and even inanimate objects.

Critics such as Rutter have also accused Bowlby of not distinguishing between deprivation and privation – the complete lack of an attachment bond, rather than its loss. Rutter stresses that the quality of the attachment bond is the most important factor, rather than just deprivation in the critical period.

Bowlby used the term maternal deprivation to refer to the separation or loss of the mother as well as the failure to develop an attachment. Are the effects of maternal deprivation as dire as Bowlby suggested?

Michael Rutter (1972) wrote a book called Maternal Deprivation Re-assessed . In the book, he suggested that Bowlby may have oversimplified the concept of maternal deprivation.

Bowlby used the term “maternal deprivation” to refer to separation from an attached figure, loss of an attached figure and failure to develop an attachment to any figure. These each have different effects, argued Rutter. In particular, Rutter distinguished between privation and deprivation.

Michael Rutter (1981) argued that if a child fails to develop an emotional bond , this is privation, whereas deprivation refers to the loss of or damage to an attachment.

Deprivation might be defined as losing something that a person once had, whereas privation might be defined as never having something in the first place.

From his survey of research on privation, Rutter proposed that it is likely to lead initially to clinging, dependent behavior, attention-seeking, and indiscriminate friendliness, then as the child matures, an inability to keep rules, form lasting relationships, or feel guilt.

He also found evidence of anti-social behavior, affectionless psychopathy, and disorders of language, intellectual development and physical growth.

Rutter argues that these problems are not due solely to the lack of attachment to a mother figure, as Bowlby claimed, but to factors such as the lack of intellectual stimulation and social experiences that attachments normally provide. In addition, such problems can be overcome later in the child’s development, with the right kind of care.

Bowlby assumed that physical separation on its own could lead to deprivation, but Rutter (1972) argues that it is the disruption of the attachment rather than the physical separation.

This is supported by Radke-Yarrow (1985), who found that 52% of children whose mothers suffered from depression were insecurely attached. This figure raised to 80% when this occurred in a context of poverty (Lyons-Ruth,1988). This shows the influence of social factors. Bowlby did not take into account the quality of the substitute care. Deprivation can be avoided if there is good emotional care after separation.

Is attachment theory sexist?

Feminist critics argue Bowlby’s attachment theory is sexist for overly emphasizing mothers as ideal caregivers while neglecting other influences like fathers (e.g., Vicedo, 2017).

His popular 1950s parenting articles reinforced gender roles by proclaiming mothers uniquely important and always available. Critics also attacked his concept “monotropy” – instincts focused on one caregiver, presumably the mother.

However, Bowlby’s academic writings use phrases like “mothers or foster-mothers,” adoptive mothers, and “mother substitutes,” acknowledging many can serve as primary caregiver.

He never scientifically stated only biological mothers suffice. While “monotropy” poorly implies a singular caregiver, Bowlby meant children form one main attachment, not only to mothers. So academically, Bowlby did not limit caregivers to mothers, though his public emphasis on maternal deprivation and parenting did reinforce gender biases.

There are implications arising from Bowlby’s work. He reinforced the idea that a mother should be the most central caregiver and that this care should be given continuously. An obvious implication is that mothers should not go out to work. There have been many attacks on this claim:

- Mothers are the exclusive carers in only a very small percentage of human societies; often there are a number of people involved in the care of children, such as relations and friends (Weisner, & Gallimore, 1977).

- Van Ijzendoorn, & Tavecchio (1987) argue that a stable network of adults can provide adequate care and that this care may even have advantages over a system where a mother has to meet all a child’s needs.

- There is evidence that children develop better with a mother who is happy in her work, than a mother who is frustrated by staying at home (Schaffer, 1990).

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1971) Individual differences in strange- situation behavior of one-year-olds. In H. R. Schaffer (Ed.) The origins of human social relations . London and New York: Academic Press. Pp. 17-58.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Alsop‐Shields, L., & Mohay, H. (2001). John Bowlby and James Robertson: theorists, scientists and crusaders for improvements in the care of children in hospital. Journal of advanced nursing , 35 (1), 50-58.

Bifulco, A., Harris, T., & Brown, G. W. (1992). Mourning or early inadequate care? Reexamining the relationship of maternal loss in childhood with adult depression and anxiety. Development and Psychopathology, 4(03) , 433-449.

Bowlby, J. (1944). Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their characters and home life. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 25(19-52) , 107-127.

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health . World Health Organization Monograph.

Bowlby, J. (1952). Maternal care and mental health. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 16(3) , 232.

Bowlby, J. (1953). Child care and the growth of love . London: Penguin Books.

Bowlby, J. (1956). Mother-child separation. Mental Health and Infant Development, 1, 117-122.

Bowlby, J. (1957). Symposium on the contribution of current theories to an understanding of child development. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 30(4) , 230-240.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss . New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness & depression. Attachment and loss (vol. 3); (International psycho-analytical library no.109). London: Hogarth Press.

Bowlby, J. (1988). Attachment, communication, and the therapeutic process. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development , 137-157.

Bowlby, J., Ainsworth, M., Boston, M., & Rosenbluth, D. (1956). The effects of mother‐child separation: a follow‐up study . British Journal of Medical Psychology , 29 (3‐4), 211-247.

Bowlby, J., and Robertson, J. (1952). A two-year-old goes to hospital. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 46, 425–427.

Bretherton, I., & Munholland, K.A. (1999). Internal working models revisited. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 89– 111) . New York: Guilford Press.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1994). Cognitive representations of adult attachment: The structure and function of working models. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.) Advances in personal relationships, Vol. 5: Attachment processes in adulthood (pp. 53-90). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Harlow, H. F., & Zimmermann, R. R. (1958). The development of affective responsiveness in infant monkeys. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 102 ,501 -509.

Hodges, J., & Tizard, B. (1989). Social and family relationships of ex‐institutional adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30(1) , 77-97.

Lorenz, K. (1935). Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Der Artgenosse als auslösendes Moment sozialer Verhaltensweisen. Journal für Ornithologie 83, 137–215.

Lyons-Ruth, K., Zoll, D., Connell, D., & Grunebaum, H. E. (1986). The depressed mother and her one-year-old infant: Environment, interaction, attachment, and infant development. In E. Tronick & T. Field (Eds.), Maternal depression and infant disturbance (pp. 61-82). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ministry of Health (1959). The Welfare of Children in Hospital, Platt Report . London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Radke-Yarrow, M., Cummings, E. M., Kuczynski, L., & Chapman, M. (1985). Patterns of attachment in two-and three-year-olds in normal families and families with parental depression. Child development , 884-893.

Robertson J. (1953). A Two-Year-Old Goes to Hospital: A Scientific Film Record (Film) . Concord Film Council, Nacton.

Robertson, J. (1955). Young children in long-term hospitals. Nursing Times , 23 (9).

Robertson, J. (1958). Going to Hospital with Mother: A Guide to the Documentary Film . Tavistock Child Development Research Unit.

Robertson, J. (1968). The long-stay child in hospital. Maternal Child Care , 4 (40), 161-6.

Robertson, J., & Robertson, J. (1968). Jane 17 months; in fostercare for 10 days. London: Tavistock Institute of Human Relations. Film .

Robertson, J., & Robertson, J. (1971). Young children in brief separation: A fresh look. The psychoanalytic study of the child , 26 (1), 264-315.

Rutter, M. (1972). Maternal deprivation reassessed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Rutter, M. (1979). Maternal deprivation, 1972-1978: New findings, new concepts, new approaches. Child Development , 283-305.

Rutter, M. (1981). Stress, coping and development: Some issues and some questions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(4) , 323-356.

Schaffer, H. R. & Emerson, P. E. (1964). The development of social attachments in infancy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 29 (3), serial number 94.

Schore, A. N. (2000). Attachment and the regulation of the right brain. Attachment & Human Development, 2(1) , 23-47.

Tavecchio, L. W., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (Eds.). (1987). Attachment in social networks: Contributions to the Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory . Elsevier.

Vicedo, M. (2020). Attachment Theory from Ethology to the Strange Situation. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology .

Weisner, T. S., & Gallimore, R. (1977). My brother’s keeper: Child and sibling caretaking. Current Anthropology, 18(2) , 169.

Further Reading

- The Internal Working Models Concept: What Do We Really Know About the Self in Relation to Others?

- The Effects of Maternal Deprivation

- Davies, R. (2010). Marking the 50th anniversary of the Platt Report: from exclusion, to toleration and parental participation in the care of the hospitalized child . Journal of Child Health Care , 14 (1), 6-23.

- Bowlby, J. (1963). Pathological mourning and childhood mourning . Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association , 11 (3), 500-541.

- Attachment Styles

- Start to Heal

For All Styles

- Attachment Repair Course

Developed by Expert Psychologists

- Emotional & Self Growth

Learn Energy Management

- Dating Toolkit

Learn the tools for dating

Anxious Attachment

How does it develop in childhood?

Avoidant Attachment

What are symptoms in adult relationships?

Disorganized Attachment

What is it like to date a disorganized adult?

Secure Attachment

The 5 conditions for secure attachment

What Is Attachment Theory?

Do you know your attachment style take our attachment quiz and find out now – fast, easy, free., in this page you’ll find:.

- The foundation of attachment theory

- The attachment classification system

- The stages of attachment

- The emotional skills we learn from attachment

- Relationships from an attachment perspective

- rief overview of our guidelines for attachment classification

- Influence on other fields and future directions

The History of Attachment Theory

Attachment theory owes its inception primarily to John Bowlby (1907-1990). Trained in psychoanalysis in the 1930s, Bowlby was not entirely satisfied with his studies. From his perspective, psychoanalysis focused too much on our internal world, and consequently ignored the environment we are immersed in [1].

During the early years of his career, Bowlby worked in a psychiatric hospital as he was also trained in developmental psychology and child psychiatry. In fact, it was in this hospital where he found the inspiration for his subsequent innovative work on attachment.

He observed that two children under his care displayed marked differences in behaviors. One child was notably distant and emotionless, while the other was constantly in his vicinity – so much so, that others started to refer to the child as Bowlby’s “shadow” [1].

Bowlby was later mentored by Melanie Klein, a highly influential name in the field, whom he later publicly disagreed with theoretically. The basis of this disagreement centered on Klein’s belief that children’s emotional problems arise solely from internal processes. In contrast to this belief, Bowlby postulated that children’s emotional problems actually arise from how they interact with their environment growing up [1].

A principal aspect of Bowlby’s later career was his focus on mother-child separation issues. He was strongly influenced by Konrad Lorenz’s work, which showed how attachment is instinctual. From Lorenz’s theory, Bowlby gleaned that a newborn baby does not solely need their mother for food, but instead desires the caregiver-child connection that builds between them [2]. Therefore, Bowlby sought to understand what would happen to children when this essential need was not met.

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

In essence, Bowlby’s attachment theory posits that attachment bonds are innate [1]. When a child’s immediate need for a secure attachment bond is not met, the child feels threatened and will react accordingly, such as by crying or calling out for their caregiver. Moreover, if the need for a stable bond is not met consistently, the infant can develop social, emotional, and even cognitive problems.

This need for attachment has catalyzed our understanding of human nature, leading up to Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary’s claim that belongingness is an essential human need, much like shelter or water [3].

The Anxious-Avoidant Spectrum

From Bowlby’s initial observations of the children with two highly distinctive behaviors at the psychiatric hospital, a spectrum of attachment behaviors came to life. We can visualize this spectrum holding attachment anxiety on one side and attachment avoidance on the other.

Given certain triggers and subsequent behaviors, one can gravitate toward either side of the spectrum. For example, an anxious attacher who hasn’t heard from their partner for a couple of hours is likely to trigger anxious attachment behaviors such as texting or calling their partner incessantly. In this case, they have demonstrated to be most certainly on the anxious side of the spectrum.

However, as was to be soon discovered through research, this anxious-avoidant spectrum didn’t fully account for the behavioral differences observed in children. There was still some information missing. Let’s dive into how attachment theory developed further.

Ainsworth and Attachment Theory: The Strange Situation

Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999) – considered to be the second founder of the field of attachment – furthered the development of Bowlby’s theory. Ainsworth crucially contributed to attachment theory with the concept of a secure base [1]. In her view, a child needs an established secure base, or dependence, with their caregivers before venturing into the exploration of the world around them.

The Strange Situation is perhaps the most well-known of Ainsworth’s main contributions [4]. The study was designed to look at the association between attachment and infants’ exploration of their surroundings.

- Children between the ages of 12 and 18 months from a sample of 100 typical American families were observed in the Strange Situation.

- A small room was set up with a one-way glass window designed to covertly observe the actions of the child. The room was filled with toys, and at first, it was just the infant and their mother.

- The Strange Situation consisted of eight steps, each of which lasted approximately 3 minutes:

- Mother and infant alone.

- A stranger enters the room.

- The mother leaves the baby and stranger alone.

- The mother returns.

- The stranger leaves.

- The mother leaves and the child is left alone.

- The stranger returns.

- Mother returns and the stranger exits.

The aim of the Strange Situation was to observe the infant’s exploratory behavior with their mother, in her absence, as well as in the presence of a stranger. This was one of the main experiments to drive the establishment of an attachment classification system. It allowed for the distinction between a child’s ambivalent and dismissing behaviors upon reuniting with their mother [1,5].

The Attachment Classification System

From the Strange Situation, Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation Classification (SSC) , which is the cornerstone of how we categorize attachment styles today. Ainsworth distinguished three attachment styles:

Secure – the child displays distress when separated from the mother, but is easily soothed and returns their positive attitude quickly when reunited with them.

Resistant – the child displays intense distress when the mother leaves but resists contact with them when reunited.

Avoidant – the child displays no distress when separated from their mother, as well as no interest in the mother’s return.

Adding Disorganized Attachment

Ainsworth had several Ph.D. students working with her – one of whom became notorious for their significant contributions to attachment theory .

Namely, Mary Main observed a unique behavior in one infant: in a moment when the infant was frightened by thunder, they surprisingly ran towards the experimenter instead of their own mother.

Based on this interaction, Main decided to focus her research on identifying peculiar behaviors such as this, leading to the identification of the fourth element in the classification of attachment: the disorganized attachment style – which incorporated both resistant and dismissing behaviors [6,7,8].

The attachment spectrum (Figure 1) stemmed from both Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s contributions to the theory.

The Stages of Attachment

In the 1960s, Rudolph Schaffer and Peggy Emerson identified that human social connections start at birth, and that the bond between an infant and caregiver only grows stronger over time. Furthermore, attachment styles also develop over time, and this was illustrated in the four stages that Schaffer and Emerson developed in 1964 [9].

Their study was conducted in such a way that babies were followed-up through interviews with their mothers, every 4 weeks throughout their first year after birth, and then one more time at 18 months. Their research resulted in the development of the following stages:

Asocial Stage 0-6 weeks. Babies don’t distinguish between humans, although there is a clear preference for humans over non-humans. The infants form attachment with anyone who comes their way.

Indiscriminate Stage 6 weeks – 6 months. The bonds with their caregivers start to grow stronger. Infants begin to distinguish people from one another, and they do not have a fear of strangers.

Specific Attachment Stage 7+ months. This is when separation anxiety becomes prevalent, particularly from their main caregivers or close adults. At this point, infants develop a feeling of distress when surrounded by strangers.

Multiple Attachments Stage 10+ months. Attachment with the infant’s primary caregiver grows even stronger. The infant is increasingly interested in creating bonds with others that are not their caregivers.

Learning Relationship Skills From Attachment

Our main attachment relationships , especially those in our earliest stages of life, have a unique influence on how we handle other relationships later on [10]. An important role that these attachment relationships have is to teach us healthy affect regulation.

Affect regulation, or emotion regulation, is the extent to which we can experience emotions and process these in a healthy way.

Emotion regulation is especially important when we encounter negative experiences. As infants, these negative experiences are a key opportunity to cultivate this skill. It is also in these moments that we learn how, or to what extent, we can rely on our caregivers to support us [11]. Thus, if we don’t feel protected or understood by our caregivers, this can teach us that they are not reliable sources of safety or love.

Moreover, we learn emotion regulation and relationship skills directly through our caregivers’ behaviors. Basically, we mirror our caregivers’ actions; for instance, if we notice that our cries bring about distress in our caregiver, we feel greater distress in return [12]. Thus, an infant develops a sense of self by assessing their impact on their surroundings. If their caregivers consistently react to the child negatively or neglect them in some way, the child will develop a distorted version of themselves and their capacity to interact with their environment [12].

Relationships Through the Lens of Attachment Theory

Today, attachment theory is regularly applied to a vast array of relationships, but this was not always the case. In the 1980s, Cindy Hazan and Philip Shaver introduced their views on attachment, arguing that its classification system could be applied to romantic relationships as well as the original caregiver-child format [10]. Their argument relied on the premise that relationships/love take many shapes and forms, and an attachment reaction typically follows.

With this perspective in mind, we can begin to see how attachment is not a static aspect of ourselves – it fluctuates depending on a specific relationship and situation. While we do have our first encounter with an attachment relationship at birth, with our caregivers, this is not the only relationship that will influence how we relate to others. From childhood onwards, the people closest to us all have an impactful role in our development.

What Is an Attachment Bond?

An attachment bond is one that we establish with the closest people in our lives, typically, our caregivers, close family, or intimate partners.

Therefore, not every relationship we have will have an attachment bond. Instead, these bonds form in the relationships with people that we need, such the ones that fulfill basic physical needs (e.g. food and shelter), or emotional needs (e.g. the need to belong).

Attachment bonds or attachment figures are the connections whose absence causes us the most suffering. For this reason, losing an attachment bond is a highly distressing experience, which is usually marked by anxiety and sadness.

However, loss can feel very different depending on the type of relationship and bond that was developed. On the flip side, reuniting with an attachment figure after some time apart can bring about immense happiness and joy, and even a sense of relief.

Our Classification of Attachment

From the inception of attachment theory onwards, vast amounts of research and studies have been conducted and published by renowned professionals. At The Attachment Project, we endeavor to keep abreast of this work and the most recent findings in the field, and use it to guide us in delivering scientifically and theoretically sound information.

Having said as much, and recognizing the evolution of attachment theory, we’ll leave you with a very brief overview of the classification of attachment as we understand it, entirely based on previous work and research:

Secure attachment is characteristic of people who easily trust others. These individuals are attuned to their own emotions and can easily attune to those of others. They are comfortable with intimacy and can easily communicate their thoughts and feelings. The secure attachment is characterized by the ability to:

- Handle conflict calmly

- Feel comfortable both in relationships and on your own

- Differentiate thoughts from feelings

- Maintain a balanced sense of self and confidence

The Conditions for Secure Attachment

Recently, a study designed to specifically examine secure attachment identified the conditions necessary to raise a securely attached child [13].

If these conditions are not met, an insecure attachment style is likely to develop. The five conditions for secure attachment are as follows:

- The child feels safe.

- The child feels seen and known.

- The child feels comfort, soothing, and reassurance.

- The child feels valued.

- The child feels supported to explore.

On the other hand, the following experiences can lead to an insecure attachment to form during childhood:

- Perceived inconsistency: The child feels incoherence in whether their needs are met. This inconsistency can be confusing for the child, who will feel that their caregiver(s) are ultimately unreliable.

- Felt rejection or neglect: Even though the caregiver(s) may not do so purposefully or knowingly, the child feels that their needs, particularly their emotional needs, are not being met. They may feel that they are not appreciated or understood for who they are.

- Sense of fear: A sense of fear can come from truly alarm-inducing situations, such as a traumatic event. However, a sense of fear also arise from seemingly simple situations that induce feelings of rejection, neglect, or that result in the sense of being unloved.

Anxious attachment (or preoccupied) can often be identified in people who essentially have an extra-sensitive nervous system. These individuals may struggle with hyperactivation of emotions, as well as hypervigilance for something going wrong. The scariest thing they can imagine is being abandoned by their loved ones.

Most likely, their attachment anxiety stems from an inconsistent parent who would be attentive at times yet misattuned at other times.

The main signs of anxious attachment are the following:

- Catastrophic thinking, such as picturing things going very wrong, very easily

- A positive view of others, but a negative view of themselves

- Putting great effort into relationships, to the extent of self-sacrifice

- Immense difficulty with receiving criticism and rejection

Avoidant attachment (or dismissive) is often present in individuals who tend to downplay their emotions or dismiss them completely. These people are typically highly independent and self-reliant, and their greatest fear is usually intimacy and vulnerability.

This attachment style tends to develop when caregivers were not emotionally attuned to their child or who were generally emotionally distant.

The main tell-tale signs of an avoidant attacher are:

- Difficulty seeking support and admitting they need help

- Extreme self-reliance and independence

- A tendency to have a positive self-view yet a negative or critical view of others

- Maintaining or increasing distance when others try to connect emotionally

Disorganized attachment (or fearful-avoidant) is typically identified in individuals who have experienced childhood trauma or abuse. [8]. The disorganized attachment style is characterized by demonstrating inconsistent behaviors and having a hard time trusting others.

This style develops in children whose caregivers were a source of perceived fear, instead of safety and connection.

Disorganized attachment can be identified from:

- Inconsistency and unpredictability

- Oscillating between avoidant and anxious behaviors

- Their caregiver, or their main source of safety as infants, was also their main source of fear

- Struggles with intimacy and building trust in others

The Attachment Style Quiz

You may have come across the Attachment Style Quiz on our website – it is our preferred method of individual assessment on attachment styles. The Experiences in Close Relationships – Relationship Structures (ECR-RS) Questionnaire, was originally developed by R. Chris Fraley and is scientifically tested and validated [14,15].

The quiz is free and easy to complete, and you can find out your attachment style in just 5 minutes. There are other assessment alternatives you may want to opt for, which we’ve outlined in our blog post on commonly used attachment style tests. One such recommended measurement is the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) , which must be conducted by a trained professional. If you want to further explore your attachment style, we suggest bringing the materials from our website (your quiz results and any relevant articles) to a mental health practitioner.

Discover your attachment style in just 5 minutes. Receive your report straight away. Totally free!

Influence and Future Directions

Attachment theory has influenced developmental psychopathology, especially the investigation of family relationships, and even the cross-cultural aspects of attachment [1].

At The Attachment Project, we seek to increase mental health awareness through informing our audience about the multiple influences of attachment on various areas of life.

For instance, there is a growing body of work on the association between organizational psychology and attachment theory psychology [20], and that line of research deals with how attachment impacts our behaviors and emotions in the workplace. Moreover, there are multiple links between attachment and a number of mental health concerns, such as eating disorders, addiction, ADHD, ASD, and issues with language development .

Another interesting connection is to be found between attachment and early maladaptive schemas. Maladaptive schemas are, in a nutshell, limiting beliefs that are formed based on repeated patterns of trauma in early childhood. Last but not least, attachment has a profound influence on many aspects of our personal relationships, such as jealousy, loneliness, and compassion.

We are eager to continue exploring the field, with the aim to help you, our readers, learn more about yourselves and gain the necessary insights to build the relationships and lives you truly want and deserve.

Curious to learn more about your attachment style?

Get your digital Attachment Style Workbook to gain a deeper understanding of…

- how your attachment style developed

- how it influences different aspects of your daily life, such as your self-image, romantic relationships, sexual life, friendships, career, and parenting skills

- how you can use the superpowers associated with your attachment style

- how you can begin cultivating a secure attachment

[1] Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28 (5), 759–775. [2]Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52 (4), 664–678. [3] Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117 (3), 497–529. [4] Ainsworth, M. D. S., Wittig, B. A. (1969). Attachment and the exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 113-136). London: Methuen. [5] Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C, Waters, E., Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum [6] Main, M. & Weston, D.R. (1981) The quality of the toddler’s relationship to mother and to father: related to conflict behavior and the readiness to establish new relationships. Child Development, 52(3), 932–40. [7] Main, M. (1999) Disorganized Attachment in Infancy, Childhood, and Adulthood: An Introduction to the Phenomena. Unpublished manuscript, Mary Main & Erik Hesse personal archive; Hinde, R. (1966, 1970) Animal Behavior, 2nd edn. New York: McGraw. [8] Main, M. & Solomon, J. (1986) Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In M. Yogman & T.B. Brazelton (eds) Affective Development in Infancy (pp.95–124.) Norwood, NJ. [9] Schaffer, H.R., Emerson, P.E. (1964). The development of social attachments in infancy. Monograph of the Society for Research in Child Development, 29(3), 1-77. [10] Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. [11] Buckholdt, K.E., Parra, G.R., Jobe-Shields, L. (2013). Intergenerational Transmission of Emotion Dysregulation Through Parental Invalidation of Emotions: Implications for Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 324-332. [12] Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Mirror-role of Mother and Family in Child Development. Chapter 9 in Winnicott, D.W. (ed.) Playing & Reality. Tavistock Publications. [13] Brown, D. P., & Elliott, D. S. (2016). Attachment disturbances in adults: Treatment for comprehensive repair. WW Norton & Co. [14] Fraley, R. C., Heffernan, M. E., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). The Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures questionnaire: A method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 615–625. [15] Fraley, R. C., Niedenthal, P. M., Marks, M. J., Brumbaugh, C. C., & Vicary, A. (2006). Adult attachment and the perception of emotional expressions: Probing the hyperactivating strategies underlying anxious attachment. Journal of Personality, 74, 1163-1190. [16] Keller, H. (2018). Universality claim of attachment theory: Children’s socioemotional development across cultures. PNAS, 115(45), 11414-11419. [17] Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., van Ijzendoorn, M.H. (2009). The fist 10,000 Adult Attachment Interviews: Distributions of adult attachment representations in clinical and non-clinical groups. Attachment & Human Development, 11(3), 223-263. [18] Sprecher, S. (2020). Trends Over Time in Emerging Adults’ Self-Reports on Attachment Styles. Emerging Adulthood, 1-6. [19] Cullen, W., Gulati, G., Kelly, B.D. (2020). Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(5), 311-312. [20] Yip, J., Ehrhardt, K., Black, H., Walker, D.O. (2017). Attachment theory at work: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 185-198.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

I would like to sign up for the newsletter I agree with terms and conditions and privacy policy

Attachment Theory (Bowlby)

Summary: Attachment theory emphasizes the importance of a secure and trusting mother-infant bond on development and well-being.

Originator and key contributors:

- John Bowlby (1907-1990) British child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, known for his theory on attachment

- Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999), American psychoanalyst known for the `strange situation`

Keywords: maternal deprivation, internal working model, strange situation, attachment styles

Attachment is described as a long lasting psychological connection with a meaningful person that causes pleasure while interacting and soothes in times of stress. The quality of attachment has a critical effect on development, and has been linked to various aspects of positive functioning, such as psychological well-being [1] .

Maternal Deprivation

Bowlby began his journey to attachment theory through research he conducted on child delinquents and hospitalized children. These studies led him to discuss the negative effects of maternal deprivation, the situation in which the mother was either non responsive or absent for long spans of time within the child’s first two years of life. Bowlby believed that children have an innate need to develop a close relationship with one main figure, usually the mother. When this does not occur, it has negative consequences on development, causing a decline in intelligence, depression, aggression, delinquency, and affectionless psychopathy (a situation in which one is not concerned about the feelings of others) [2] .

Bowlby’s theory on attachment

Following the above conclusions regarding maternal deprivation, Bowlby sought to develop a theory which would support and explain his results. He felt that existing theories on attachment from psychoanalytic and behavioral fields were detached from reality and not up to date, thus he began reading into and corresponding with current researchers in the fields of biology and ethology. One study which was particularly influential on attachment theory was conducted by Harlow & Zimmerman in 1959 [3] . In this study, monkeys were separated from their mothers and put into cages with “surrogate mothers”. One “mother” was made out of wire with an attached bottle, while the other was coated with cloth. The study’s results showed that monkeys chose the cloth mother over the wire mother, even though she did not offer food. These results stand in contrast to classic approaches to attachment which believed that the goal of attachment was the fulfillment of needs, particularly feeding. Bowlby developed his theory on the basis of these results, claiming attachment to be an intrinsic need for an emotional bond with one’s mother, extending beyond the need to be fed. He believed this to be an evolved need, where a strong emotional bond with one’s mother increases chances of survival.

Stages of attachment

Preattachment (newborn-6 weeks): Newborn infants know to act in such a way that attracts adults, such as crying, smiling, cooing, and making eye contact. Although not attached to their mothers yet, they are soothed by the presence of others.

Attachment in making (6 weeks- 6 to 8 months): Infants begins to develop a sense of trust in their mothers, in that they can depend on her in times of need. They are soothed more quickly by their mother, and smile more often next to her.

Clear cut attachment (6 to 8 months- 18 months to 2 years): Attachment is established. The infant prefers his mother over anyone else, and experiences separation anxiety when she leaves. The intensity of separation anxiety is influenced by the infant’s temperament and the way in which caregivers respond and soothe the infant.

Formation of reciprocal relationship (18 months- to years +): As language develops, separation anxiety declines. The infant can now understand when his mother is leaving and when she will be coming back. In addition, a sense of security has developed, in that even when his mother is not physically there, he knows she is always there for him. Bowlby called this sense of security an internal working model.

Attachment styles

Bowlby’s attachment theory was tested using the `strange situation`. Children’s responses to their mother’s presence and absence, and that of a stranger, were recorded [4] . These results served as the basis for the formulation of attachment styles.

Secure attachment – Children who have developed secure attachment feel secure and happy, and are eager to explore their surroundings. They know they could trust their mother to be there for them. Although distressed at their mother’s absence, they are assured she will return. The mother’s behavior is consistent and sensitive to the needs of her child.

Anxious avoidant insecure attachment : Children who have developed an anxious avoidant insecure attachment do not trust their mother to fulfill their needs. They act indifferent to their mother’s presence or absence, but are anxious inside. They are not explorative, and are emotionally distant. The mother’s behavior is disengaged from her child and emotionally distant.

Anxious resistant insecure (ambivalent) attachment – Children who have developed anxious resistant insecure attachment show a mixture of anger and helplessness towards their mother. They acts passively, and feel insecure. Experience has taught them that they cannot rely on their mother. The mother’s behavior is inconsistent. At times she is responsive and at times neglects her child.

Disorganized/disoriented attachment- Children who do not fit into the other categories are included in this fourth form of attachment. These children could act depressed, angry, passive, or apathetical. Their mothers could act in varying extremes, such as swaying between passivity and aggression or being scared and actually being scary.

For more information, please see:

- https://youtu.be/s14Q-_Bxc_U An excerpt from the documentary on hospitalized children which served as the basis for Bowlby’s ideas on maternal deprivation.

- A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development – one of the books written by Bowlby

- Bowlby, J. (2008). Attachment . Basic books.

- Bowlby, J. (1998). Attachment and loss (No. 3). Random House.

- Harlow, H. F., & Zimmerman, R. R. (1959). Affectional Response in the Infant Monke’. Science , 130 (3373), 421-431.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. N. (2015). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . Psychology Press.

Related Posts

Dunning-Krueger Effect

Confirmation Bias (Wason)

Situated Learning Theory (Lave)

Stereotype Threat (Steele, Aronson)

Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory for Beginners

Who is John Bowlby?

John Bowlby (1907-1990) worked as both a psychologist and a psychoanalyst. You may be familiar with the term “psychoanalyst” as being chiefly associated with the work of Sigmund Freud. It consists of the belief that all people possess thoughts, feelings and memories in their unconscious.

Bowlby’s work revolved around his theory that attachments formed in early childhood were vital in the future emotional development of the child. He also believed that people are born with an inherent instinct to form close relationships and attachments to certain figures in order to gain protection and stability.

Bowlby grew up in a household where time spent with his parents was carefully rationed, as they believed that too much affection and attention would spoil their child. As a result, Bowlby was sent to boarding school at the age of seven, an experience which had a very negative effect on him. During and after his studies at Cambridge, Bowlby worked with delinquent and maladjusted children, which led to him deciding to pursue a career as a child psychologist.

As a result of this work, Bowlby became interested in child development and took a special interest in how separation from caring adults affected children. The beginnings of his attachment theory came in 1949 when his employer, the World Health Organisation, asked him to write a report on the mental health of homeless children.

The work took two years to complete and was published under the title “Maternal Care and Mental Health”. In this report, Bowlby stressed the importance of a close and continuous relationship with a mother figure. His training as a psychoanalyst contributed to his belief that the first experiences in life leave a lasting impression on future development.

Bowlby’s work left a lasting impact on his successors, not least on his colleague Mary Ainsworth who continued his work and expanded upon it, devising a way of observing the attachment theory in progress. Other researchers used his work to develop clinical treatments and prevention strategies.

Such was the influence of his work that in 2002, twelve years after his death, Bowlby was ranked 49th in a survey of the twentieth century’s most frequently cited psychologists.

What is Bowlby’s attachment theory?

The attachment theory describes a long-running, continual connection with a person or persons which provides satisfaction during interaction and comfort during difficult times.

This attachment needs to be of a high quality if the child’s emotional development is to be steady and progressive. Bowlby’s theory centres around a single attachment between a child and their caregiver.

This does not rule out the possibility of the child forming more than one attachment to other figures, but attachment theory focuses on the significance of the mother, considering the relationship between mother and child to be unique. He suggested that a lack of maternal attachment would result in serious negative consequences.

Bowlby’s research identified four stages of attachment, with the child progressing to each as they age. Pre-attachment lasts from birth to six weeks. At this stage, the infant is comforted by the presence of others and knows that actions such as crying and cooing are effective in attracting attention.

Attachment in making lasts from the age of six weeks to 6-8 months and sees a sense of trust begin to emerge between the child and the mother. Smiling occurs more frequently during this stage. Between 6-8 months and 18 months to one year of age, clear cut attachment sees attachment established more firmly.

Finally, starting from the age of eighteen months, a reciprocal relationship is formed. A sense of security is in place and the child can now manage periods without their mother present without the risk of separation anxiety. Bowlby termed this sense of security as an interior working model.

The attachment theory states that the first two years of a child’s life are crucial in the development stage. The attachment has to be maintained continuously for this period of time if the child is to develop steadily. If the attachment is disrupted at any point during this stage, the child is exposed to potentially permanent negative cognitive, social or emotional consequences. Bowlby coined the phrase “maternal deprivation” to describe this separation. Potential results of maternal deprivation include delinquency, depression, a reduction in intelligence and an above-average level of aggressiveness.

Bowlby worked with James Robertson to develop the theory that short-term separation resulted in distress for the child. They observed that this distress manifested in three stages: at the protest stage, the child screams, cries or otherwise expresses their desire not to be separated from their attachment figure.

It is at this stage when the child may become clingy. The second stage was termed as “despair” and is characterised by the child ceasing their audible protestations and instead becoming withdrawn, uninterested and consistently refusing all offers of love and support from others.

The final stage is “detachment” and this sees the child begin to adapt to their new surroundings, interacting with other people and a gradual regaining of enthusiasm. However, when the attachment figure comes into contact with them again, the child will display anger and resentment and otherwise reject their original attachment figure.

Attachment theory today

Attachment theory is not without its critics. Some psychologists point to its overlooking of the rest of the family as a major shortcoming. Others have argued that such a focus on a single relationship overlooks social and racial issues which may also be instrumental in the child’s development and personality.

Attachment theory remains precisely that – a theory – but its influence and ability to provide psychologists with a platform on which to build, expand and test their own theories is unmistakable.

Copyright Open College UK Ltd

Please feel free to link to this post. Please do not copy – its owned.

Open College UK are a Registered Member & Approved Training Centre of the Complementary Medical Association CMA Open College UK are a Registered Learning Provider – Registration Number: UKPRN: 10021628 Open College UK are a Recognised Registered Member of the FSB – Federation of Small Businesses: 51324567 Accredited by the SFTR – National UK Therapists Register – (SFTR Accredited Courses) Recognised UK Online Qualifications available from ETA Awards, Gatehouse Awards, CPD, IATP, IIRSM, NVQ and ILM. RoSPA Approved , endorsed by the Institute of Hospitality , Recognised Training by the Institution of Fire Engineers . Company Director and website owner is fully qualified therapist. SHTC Entry Level & Practitioner Level Accreditation & Membership Availability Open College UK Ltd – Registered D-U-N-S® Number: 346575066 Category – UK Limited Company – Education Classification (SIC) – Technical & vocational secondary education (85320) Open College UK Ltd is a fully GDPR compliant and ICO registered Company. ICO Registration number: ZA361896 Organisationally Validated SSL Secure Website. Open College UK Ltd has been validated by GeoTrust Inc. Registered Limited Company – Open College UK Ltd – Company Registration Number: 5462919 – Registered In England Company VAT Registration Number: GB861328133

Trade Marks: Open College™ – Open College UK™ – Open College Courses™ The Open College™ name/s is property of Open College UK Ltd. All content unless stated otherwise is owned property of this Company.

Open College Registered Business Office Address: Open College UK Limited, Kingsway House Business Centre, 40 Foregate Street, Worcester, WR1 1EE.

Contact us | T & Cs | Google Search | Company Blog | Disclaimer | Articles | ADHD Course

Copyright Open College UK Ltd 2003-2024 All rights reserved.

John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory and Developmental Phases

A Comprehensive Guide for Early Years Professionals and Students

John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory is a psychological theory that revolutionised our understanding of child development. Created by British psychoanalyst John Bowlby in the mid-20th century, this theory emphasises the importance of early relationships in shaping a child’s emotional and social development.

Attachment Theory is used for understanding how children form bonds with their primary caregivers and how these early experiences influence their later relationships and emotional well-being. It has had a significant effect on shaping early years practice, informing how professionals approach childcare and education.

Key ideas include:

- The importance of responsive caregiving

- The concept of a ‘secure base’ for exploration and learning

- The impact of early experiences on later relationships

Practical applications of Bowlby’s work abound in Early Years settings. From implementing key person approaches to designing transition strategies, his ideas shape how we support children’s development. Understanding attachment theory enables practitioners to create nurturing environments that promote secure relationships and emotional resilience.

This comprehensive guide covers:

- Bowlby’s life and influences

- Key concepts of attachment theory

- Practical applications in Early Years settings

- Critiques and ongoing debates

- Contemporary research and future directions

This comprehensive guide explores Bowlby’s life and influences, key concepts of Attachment Theory, its practical applications in early years settings, critiques and ongoing debates, and contemporary research and future directions. Whether you’re a seasoned practitioner or a student entering the field, this article offers valuable insights into one of the most influential theories in child development.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week.

Introduction and Background to John Bowlby’s Work