Motivation Theories and Principles Essay

Introduction, theories of motivation, works cited.

People always engage in various activities throughout their lives. The main reason as to why human beings do various things is because they have a purpose that drives them every time. According to experts, motivation refers to a psychological feature that arouses someone to act towards a desired goal. It gives someone a reason and energy to take action. Motivation gives purpose and direction to behavior (Beck 30).

Studies have established that motivation plays a crucial role in the ability of human beings to set and achieve their goals. For example, people have the ability to determine their level of motivation by identifying various needs, understanding the requirements for meeting them, and using numerous abilities to achieve satisfaction. Basically, the concept of motivation involves the elements of needs, behavior, and satisfaction (Beck 45).

People have needs to meet and rely on their abilities to achieve satisfaction. There are two types of motivation, namely intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation refers to a reason for action derived from within an individual’s fundamental nature (Beck 52). On the other hand, extrinsic motivation refers to an incentive that gives purpose and direction to behavior influenced by external forces (Beck 52).

According to experts, there are numerous theories of motivation. The various theorists who explain this concept use certain beliefs that explain factors that influence human behavior. Some of the common hypotheses used to explain motivation include the drive or needs theory and arousal theory. According to the drive theory of motivation, human beings have needs that must be met in order to have the required level motivation (Beck 100).

There are five levels of human needs, namely psychological, safety, social, admiration, and self-actualization (Beck 100). According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it is important to meet the lowest ranked needs in the hierarchy before those in the higher level are triggered (Beck 104). The higher someone goes in the hierarchy, the more motivation one gets. According to experts, people get the drive to push for their goals in life whenever they have enough motivation and belief to do it.

According to the arousal theory of motivation people are driven into doing certain things in life in order to maintain a state of heightened physiological activity (Beck 123). Experts argue that people often feel bored when their levels of arousal are low. In such situations, people often look out for ways of elevating their arousal levels using various stimulating activities. A good example is people who go to night clubs or engage in sporting activities because it helps to keep their arousal levels high.

However, in some instances the arousal level can be very high and unpleasant. In such cases, people often look out for more relaxed environments or activities that can help them lower the stimulation (Beck 129). A good example is sleeping, going for a walk, or watching a romantic movie. It is important to understand that optimal states of heightened physiological activity vary from one person to another, depending on one’s needs (Beck 140).

Motivation plays a crucial role in the ability of living organisms to set and achieve their goals. There are two types of motivation, namely intrinsic and extrinsic. People get the drive to push for their goals in life whenever they have enough motivation and belief to do it. However, it is important to note that people require different levels of motivation to achieve satisfaction depending on their needs.

Beck, Robert. Motivation: Theories and Principles . New York: Pearson Hall, 2004. Print.

- Education, Behavior and Motivation Theories

- Teen Suicide Prevention Website

- Why Intrinsic Motivation Is Better Than Extrinsic Motivation

- Humans Behavior: Physical and Psychological Needs

- Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards, Power and Imbalanced Exchange

- Procrastination in the Fields of Education and Psychology

- The Media Portrayals of Sexuality and Its Effects

- Social Dynamics Inclusion in Prevention Programs

- Students Behavior Observations and Assessments

- Social Influences on Human Behavior

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, June 30). Motivation Theories and Principles. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories-and-principles/

"Motivation Theories and Principles." IvyPanda , 30 June 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories-and-principles/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Motivation Theories and Principles'. 30 June.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Motivation Theories and Principles." June 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories-and-principles/.

1. IvyPanda . "Motivation Theories and Principles." June 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories-and-principles/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Motivation Theories and Principles." June 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories-and-principles/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Module 11: Motivation

The importance of employee motivation, learning outcomes.

- Explain the importance of employee motivation in an organization.

- Distinguish between internal and external motivation.

Employee motivation is of great concern to any organization. Gallup’s 2017 survey on employee engagement shows that “the ratio of disengaged to actively engaged employees is 2-to-1, meaning that the vast majority of U.S. workers (67%) are not reaching their full potential.” [1]

Research has shown that companies with higher ratios of engaged employees experience higher earnings per share (EPS) compared with their competition. [2]

Think about what motivates you to get your homework done. Maybe you want to get an A in the class so you can make the dean’s list this term. Or maybe you want to learn all about management so you can start your own successful business one day. Because we are not all motivated by the same things, a manager’s ability to motivate employees requires gaining an understanding of the different types of motivation. A better understanding will enable you to better identify the best ways to motivate others—and possibly even yourself.

Practice Question

Types of motivation.

Motivation is the collection of factors that affect what people choose to do, and how much time and effort they put into doing it. There are two forms of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic . These forms refer to the origin of the motivation. Intrinsic motivation exists within a person; extrinsic motivation comes from external or outside sources.

Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation includes many internal sources of motivation. These might include:

- personal enjoyment and pleasure

- sense of accomplishment

- personal pride

- skill development and competency

- social status

You should notice that these intrinsic rewards are not tangible, meaning that they can’t be easily measured or quantified. Over time, however, the outgrowth may be tangible via promotions, better projects to work on, and the power to influence decisions.

Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation includes motivational stimuli that come from outside the individual. These stimuli take the form of tangible rewards, such as commissions, bonuses, raises, promotions, and additional time off from work. For example, an employee who will take on extra work, provided there is a sufficient reward for this extra effort, is extrinsically motivated. Extrinsically motivated people may also value the intrinsic rewards, but only if the extrinsic reward is sufficient.

Seldom is anyone exclusively intrinsically or extrinsically motivated. Even though someone may have strong preferences, they can overlap depending on the circumstances.

Candela Citations

- Importance of Employee Motivation. Authored by : David J. Thompson and Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image: We Can Do It!. Authored by : Office for Emergency Management, War Production Board. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:We_Can_Do_It!_(3678696585).jpg . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- “State of the American Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for U.S. Business Leaders,” Gallup, 2017 ↵

- Gallup, 2017 ↵

14.3 Process Theories of Motivation

- Describe the process theories of motivation, and compare and contrast the main process theories of motivation: operant conditioning theory, equity theory, goal theory, and expectancy theory.

Process theories of motivation try to explain why behaviors are initiated. These theories focus on the mechanism by which we choose a target, and the effort that we exert to “hit” the target. There are four major process theories: (1) operant conditioning, (2) equity, (3) goal, and (4) expectancy.

Operant Conditioning Theory

Operant conditioning theory is the simplest of the motivation theories. It basically states that people will do those things for which they are rewarded and will avoid doing things for which they are punished. This premise is sometimes called the “law of effect.” However, if this were the sum total of conditioning theory, we would not be discussing it here. Operant conditioning theory does offer greater insights than “reward what you want and punish what you don’t,” and knowledge of its principles can lead to effective management practices.

Operant conditioning focuses on the learning of voluntary behaviors. 18 The term operant conditioning indicates that learning results from our “operating on” the environment. After we “operate on the environment” (that is, behave in a certain fashion), consequences result. These consequences determine the likelihood of similar behavior in the future. Learning occurs because we do something to the environment. The environment then reacts to our action, and our subsequent behavior is influenced by this reaction.

The Basic Operant Model

According to operant conditioning theory , we learn to behave in a particular fashion because of consequences that resulted from our past behaviors. 19 The learning process involves three distinct steps (see Table 14.2 ). The first step involves a stimulus (S). The stimulus is any situation or event we perceive that we then respond to. A homework assignment is a stimulus. The second step involves a response (R), that is, any behavior or action we take in reaction to the stimulus. Staying up late to get your homework assignment in on time is a response. (We use the words response and behavior interchangeably here.) Finally, a consequence (C) is any event that follows our response and that makes the response more or less likely to occur in the future. If Colleen Sullivan receives praise from her superior for working hard, and if getting that praise is a pleasurable event, then it is likely that Colleen will work hard again in the future. If, on the other hand, the superior ignores or criticizes Colleen’s response (working hard), this consequence is likely to make Colleen avoid working hard in the future. It is the experienced consequence (positive or negative) that influences whether a response will be repeated the next time the stimulus is presented.

Reinforcement occurs when a consequence makes it more likely the response/behavior will be repeated in the future. In the previous example, praise from Colleen’s superior is a reinforcer. Extinction occurs when a consequence makes it less likely the response/behavior will be repeated in the future. Criticism from Colleen’s supervisor could cause her to stop working hard on any assignment.

There are three ways to make a response more likely to recur: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and avoidance learning. In addition, there are two ways to make the response less likely to recur: nonreinforcement and punishment.

Making a Response More Likely

According to reinforcement theorists, managers can encourage employees to repeat a behavior if they provide a desirable consequence, or reward, after the behavior is performed. A positive reinforcement is a desirable consequence that satisfies an active need or that removes a barrier to need satisfaction. It can be as simple as a kind word or as major as a promotion. Companies that provide “dinners for two” as awards to those employees who go the extra mile are utilizing positive reinforcement. It is important to note that there are wide variations in what people consider to be a positive reinforcer. Praise from a supervisor may be a powerful reinforcer for some workers (like high-nAch individuals) but not others.

Another technique for making a desired response more likely to be repeated is known as negative reinforcement . When a behavior causes something undesirable to be taken away, the behavior is more likely to be repeated in the future. Managers use negative reinforcement when they remove something unpleasant from an employee’s work environment in the hope that this will encourage the desired behavior. Ted doesn’t like being continually reminded by Philip to work faster (Ted thinks Philip is nagging him), so he works faster at stocking shelves to avoid being criticized. Philip’s reminders are a negative reinforcement for Ted.

Approach using negative reinforcement with extreme caution. Negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment. Punishment, unlike reinforcement (negative or positive), is intended to make a particular behavior go away (not be repeated). Negative reinforcement, like positive reinforcement, is intended to make a behavior more likely to be repeated in the future. In the previous example, Philip’s reminders simultaneously punished one behavior (slow stocking) and reinforced another (faster stocking). The difference is often a fine one, but it becomes clearer when we identify the behaviors we are trying to encourage (reinforcement) or discourage (punishment).

A third method of making a response more likely to occur involves a process known as avoidance learning. Avoidance learning occurs when we learn to behave in a certain way to avoid encountering an undesired or unpleasant consequence. We may learn to wake up a minute or so before our alarm clock rings so we can turn it off and not hear the irritating buzzer. Some workers learn to get to work on time to avoid the harsh words or punitive actions of their supervisors. Many organizational discipline systems rely heavily on avoidance learning by using the threat of negative consequences to encourage desired behavior. When managers warn an employee not to be late again, when they threaten to fire a careless worker, or when they transfer someone to an undesirable position, they are relying on the power of avoidance learning.

Making a Response Less Likely

At times it is necessary to discourage a worker from repeating an undesirable behavior. The techniques managers use to make a behavior less likely to occur involve doing something that frustrates the individual’s need satisfaction or that removes a currently satisfying circumstance. Punishment is an aversive consequence that follows a behavior and makes it less likely to reoccur.

Note that managers have another alternative, known as nonreinforcement , in which they provide no consequence at all following a worker’s response. Nonreinforcement eventually reduces the likelihood of that response reoccurring, which means that managers who fail to reinforce a worker’s desirable behavior are also likely to see that desirable behavior less often. If Philip never rewards Ted when he finishes stocking on time, for instance, Ted will probably stop trying to beat the clock. Nonreinforcement can also reduce the likelihood that employees will repeat undesirable behaviors, although it doesn’t produce results as quickly as punishment does. Furthermore, if other reinforcing consequences are present, nonreinforcement is unlikely to be effective.

While punishment clearly works more quickly than does nonreinforcement, it has some potentially undesirable side effects. Although punishment effectively tells a person what not to do and stops the undesired behavior, it does not tell them what they should do. In addition, even when punishment works as intended, the worker being punished often develops negative feelings toward the person who does the punishing. Although sometimes it is very difficult for managers to avoid using punishment, it works best when reinforcement is also used. An experiment conducted by two researchers at the University of Kansas found that using nonmonetary reinforcement in addition to punitive disciplinary measures was an effective way to decrease absenteeism in an industrial setting. 20

Schedules of Reinforcement

When a person is learning a new behavior, like how to perform a new job, it is desirable to reinforce effective behaviors every time they are demonstrated (this is called shaping ). But in organizations it is not usually possible to reinforce desired behaviors every time they are performed, for obvious reasons. Moreover, research indicates that constantly reinforcing desired behaviors, termed continuous reinforcement, can be detrimental in the long run. Behaviors that are learned under continuous reinforcement are quickly extinguished (cease to be demonstrated). This is because people will expect a reward (the reinforcement) every time they display the behavior. When they don’t receive it after just a few times, they quickly presume that the behavior will no longer be rewarded, and they quit doing it. Any employer can change employees’ behavior by simply not paying them!

If behaviors cannot (and should not) be reinforced every time they are exhibited, how often should they be reinforced? This is a question about schedules of reinforcement , or the frequency at which effective employee behaviors should be reinforced. Much of the early research on operant conditioning focused on the best way to maintain the performance of desired behaviors. That is, it attempted to determine how frequently behaviors need to be rewarded so that they are not extinguished. Research zeroed in on four types of reinforcement schedules:

Fixed Ratio. With this schedule, a fixed number of responses (let’s say five) must be exhibited before any of the responses are reinforced. If the desired response is coming to work on time, then giving employees a $25 bonus for being punctual every day from Monday through Friday would be a fixed ratio of reinforcement.

Variable Ratio. A variable-ratio schedule reinforces behaviors, on average, a fixed number of times (again let’s say five). Sometimes the tenth behavior is reinforced, other times the first, but on average every fifth response is reinforced. People who perform under such variable-ratio schedules like this don’t know when they will be rewarded, but they do know that they will be rewarded.

Fixed Interval. In a fixed-interval schedule, a certain amount of time must pass before a behavior is reinforced. With a one-hour fixed-interval schedule, for example, a supervisor visits an employee’s workstation and reinforces the first desired behavior she sees. She returns one hour later and reinforces the next desirable behavior. This schedule doesn’t imply that reinforcement will be received automatically after the passage of the time period. The time must pass and an appropriate response must be made.

Variable Interval. The variable interval differs from fixed-interval schedules in that the specified time interval passes on average before another appropriate response is reinforced. Sometimes the time period is shorter than the average; sometimes it is longer.

Which type of reinforcement schedule is best? In general, continuous reinforcement is best while employees are learning their jobs or new duties. After that, variable-ratio reinforcement schedules are superior. In most situations the fixed-interval schedule produces the least effective results, with fixed ratio and variable interval falling in between the two extremes. But remember that effective behaviors must be reinforced with some type of schedule, or they may become extinguished.

Equity Theory

Suppose you have worked for a company for several years. Your performance has been excellent, you have received regular pay increases, and you get along with your boss and coworkers. One day you come to work to find that a new person has been hired to work at the same job that you do. You are pleased to have the extra help. Then, you find out the new person is making $100 more per week than you, despite your longer service and greater experience. How do you feel? If you’re like most of us, you’re quite unhappy. Your satisfaction has just evaporated. Nothing about your job has changed—you receive the same pay, do the same job, and work for the same supervisor. Yet, the addition of one new employee has transformed you from a happy to an unhappy employee. This feeling of unfairness is the basis for equity theory.

Equity theory states that motivation is affected by the outcomes we receive for our inputs compared to the outcomes and inputs of other people. 21 This theory is concerned with the reactions people have to outcomes they receive as part of a “social exchange.” According to equity theory, our reactions to the outcomes we receive from others (an employer) depend both on how we value those outcomes in an absolute sense and on the circumstances surrounding their receipt. Equity theory suggests that our reactions will be influenced by our perceptions of the “inputs” provided in order to receive these outcomes (“Did I get as much out of this as I put into it?”). Even more important is our comparison of our inputs to what we believe others received for their inputs (“Did I get as much for my inputs as my coworkers got for theirs?”).

The Basic Equity Model

The fundamental premise of equity theory is that we continuously monitor the degree to which our work environment is “fair.” In determining the degree of fairness, we consider two sets of factors, inputs and outcomes (see Exhibit 14.11 ). Inputs are any factors we contribute to the organization that we feel have value and are relevant to the organization. Note that the value attached to an input is based on our perception of its relevance and value. Whether or not anyone else agrees that the input is relevant or valuable is unimportant to us. Common inputs in organizations include time, effort, performance level, education level, skill levels, and bypassed opportunities. Since any factor we consider relevant is included in our evaluation of equity, it is not uncommon for factors to be included that the organization (or even the law) might argue are inappropriate (such as age, sex, ethnic background, or social status).

Outcomes are anything we perceive as getting back from the organization in exchange for our inputs. Again, the value attached to an outcome is based on our perceptions and not necessarily on objective reality. Common outcomes from organizations include pay, working conditions, job status, feelings of achievement, and friendship opportunities. Both positive and negative outcomes influence our evaluation of equity. Stress, headaches, and fatigue are also potential outcomes. Since any outcome we consider relevant to the exchange influences our equity perception, we frequently include unintended factors (peer disapproval, family reactions).

Equity theory predicts that we will compare our outcomes to our inputs in the form of a ratio. On the basis of this ratio we make an initial determination of whether or not the situation is equitable. If we perceive that the outcomes we receive are commensurate with our inputs, we are satisfied. If we believe that the outcomes are not commensurate with our inputs, we are dissatisfied. This dissatisfaction can lead to ineffective behaviors for the organization if they continue. The key feature of equity theory is that it predicts that we will compare our ratios to the ratios of other people. It is this comparison of the two ratios that has the strongest effect on our equity perceptions. These other people are called referent others because we “refer to” them when we judge equity. Usually, referent others are people we work with who perform work of a similar nature. That is, referent others perform jobs that are similar in difficulty and complexity to the employee making the equity determination (see Exhibit 14.11 ).

Three conditions can result from this comparison. Our outcome-to-input ratio could equal the referent other’s. This is a state of equity . A second result could be that our ratio is greater than the referent other’s. This is a state of overreward inequity . The third result could be that we perceive our ratio to be less than that of the referent other. This is a state of underreward inequity .

Equity theory has a lot to say about basic human tendencies. The motivation to compare our situation to that of others is strong. For example, what is the first thing you do when you get an exam back in class? Probably look at your score and make an initial judgment as to its fairness. For a lot of people, the very next thing they do is look at the scores received by fellow students who sit close to them. A 75 percent score doesn’t look so bad if everyone else scored lower! This is equity theory in action.

Most workers in the United States are at least partially dissatisfied with their pay. 22 Equity theory helps explain this. Two human tendencies create feelings of inequity that are not based in reality. One is that we tend to overrate our performance levels. For example, one study conducted by your authors asked more than 600 employees to anonymously rate their performance on a 7-point scale (1 = poor, 7 = excellent). The average was 6.2, meaning the average employee rated his or her performance as very good to excellent. This implies that the average employee also expects excellent pay increases, a policy most employers cannot afford if they are to remain competitive. Another study found that the average employee (one whose performance is better than half of the other employees and worse than the other half) rated her performance at the 80th percentile (better than 80 percent of the other employees, worse than 20 percent). 23 Again it would be impossible for most organizations to reward the average employee at the 80th percentile. In other words, most employees inaccurately overrate the inputs they provide to an organization. This leads to perceptions of inequity that are not justified.

The second human tendency that leads to unwarranted perceptions of inequity is our tendency to overrate the outcomes of others. 24 Many employers keep the pay levels of employees a “secret.” Still other employers actually forbid employees to talk about their pay. This means that many employees don’t know for certain how much their colleagues are paid. And, because most of us overestimate the pay of others, we tend to think that they’re paid more than they actually are, and the unjustified perceptions of inequity are perpetuated.

The bottom line for employers is that they need to be sensitive to employees’ need for equity. Employers need to do everything they can to prevent feelings of inequity because employees engage in effective behaviors when they perceive equity and ineffective behaviors when they perceive inequity.

Perceived Overreward Inequity

When we perceive that overreward inequity exists (that is, we unfairly make more than others), it is rare that we are so dissatisfied, guilty, or sufficiently motivated that we make changes to produce a state of perceived equity (or we leave the situation). Indeed, feelings of overreward, when they occur, are quite transient. Very few of us go to our employers and complain that we’re overpaid! Most people are less sensitive to overreward inequities than they are to underreward inequities. 25 However infrequently they are used for overreward, the same types of actions are available for dealing with both types of inequity.

Perceived Underreward Inequity

When we perceive that underreward inequity exists (that is, others unfairly make more than we do), we will likely be dissatisfied, angered, and motivated to change the situation (or escape the situation) in order to produce a state of perceived equity. As we discuss shortly, people can take many actions to deal with underreward inequity.

Reducing Underreward Inequity

A simple situation helps explain the consequences of inequity. Two automobile workers in Detroit, John and Mary, fasten lug nuts to wheels on cars as they come down the assembly line, John on the left side and Mary on the right. Their inputs are equal (both fasten the same number of lug nuts at the same pace), but John makes $500 per week and Mary makes $600. Their equity ratios are thus:

As you can see, their ratios are not equal; that is, Mary receives greater outcome for equal input. Who is experiencing inequity? According to equity theory, both John and Mary—underreward inequity for John, and overreward inequity for Mary. Mary’s inequity won’t last long (in real organizations), but in our hypothetical example, what might John do to resolve this?

Adams identified a number of things people do to reduce the tension produced by a perceived state of inequity. They change their own outcomes or inputs, or they change those of the referent other. They distort their own perceptions of the outcomes or inputs of either party by using a different referent other, or they leave the situation in which the inequity is occurring.

- Alter inputs of the person. The perceived state of equity can be altered by changing our own inputs, that is, by decreasing the quantity or quality of our performance. John can affect his own mini slowdown and install only nine lug nuts on each car as it comes down the production line. This, of course, might cause him to lose his job, so he probably won’t choose this alternative.

- Alter outcomes of the person. We could attempt to increase outcomes to achieve a state of equity, like ask for a raise, a nicer office, a promotion, or other positively valued outcomes. So John will likely ask for a raise. Unfortunately, many people enhance their outcomes by stealing from their employers.

- Alter inputs of the referent other. When underrewarded, we may try to achieve a state of perceived equity by encouraging the referent other to increase their inputs. We may demand, for example, that the referent other “start pulling their weight,” or perhaps help the referent other to become a better performer. It doesn’t matter that the referent other is already pulling their weight—remember, this is all about perception. In our example, John could ask Mary to put on two of his ten lug nuts as each car comes down the assembly line. This would not likely happen, however, so John would be motivated to try another alternative to reduce his inequity.

- Alter outcomes of the referent other. We can “correct” a state of underreward by directly or indirectly reducing the value of the other’s outcomes. In our example, John could try to get Mary’s pay lowered to reduce his inequity. This too would probably not occur in the situation described.

- Distort perceptions of inputs or outcomes. It is possible to reduce a perceived state of inequity without changing input or outcome. We simply distort our own perceptions of our inputs or outcomes, or we distort our perception of those of the referent other. Thus, John may tell himself that “Mary does better work than I thought” or “she enjoys her work much less than I do” or “she gets paid less than I realized.”

- Choose a different referent other. We can also deal with both over- and underreward inequities by changing the referent other (“my situation is really more like Ahmed’s”). This is the simplest and most powerful way to deal with perceived inequity: it requires neither actual nor perceptual changes in anybody’s input or outcome, and it causes us to look around and assess our situation more carefully. For example, John might choose as a referent other Bill, who installs dashboards but makes less money than John.

- Leave the situation. A final technique for dealing with a perceived state of inequity involves removing ourselves from the situation. We can choose to accomplish this through absenteeism, transfer, or termination. This approach is usually not selected unless the perceived inequity is quite high or other attempts at achieving equity are not readily available. Most automobile workers are paid quite well for their work. John is unlikely to find an equivalent job, so it is also unlikely that he will choose this option.

Implications of Equity Theory

Equity theory is widely used, and its implications are clear. In the vast majority of cases, employees experience (or perceive) underreward inequity rather than overreward. As discussed above, few of the behaviors that result from underreward inequity are good for employers. Thus, employers try to prevent unnecessary perceptions of inequity. They do this in a number of ways. They try to be as fair as possible in allocating pay. That is, they measure performance levels as accurately as possible, then give the highest performers the highest pay increases. Second, most employers are no longer secretive about their pay schedules. People are naturally curious about how much they are paid relative to others in the organization. This doesn’t mean that employers don’t practice discretion—they usually don’t reveal specific employees’ exact pay. But they do tell employees the minimum and maximum pay levels for their jobs and the pay scales for the jobs of others in the organization. Such practices give employees a factual basis for judging equity.

Supervisors play a key role in creating perceptions of equity. “Playing favorites” ensures perceptions of inequity. Employees want to be rewarded on their merits, not the whims of their supervisors. In addition, supervisors need to recognize differences in employees in their reactions to inequity. Some employees are highly sensitive to inequity, and a supervisor needs to be especially cautious around them. 26 Everyone is sensitive to reward allocation. 27 But “equity sensitives” are even more sensitive. A major principle for supervisors, then, is simply to implement fairness. Never base punishment or reward on whether or not you like an employee. Reward behaviors that contribute to the organization, and discipline those that do not. Make sure employees understand what is expected of them, and praise them when they do it. These practices make everyone happier and your job easier.

Goal Theory

No theory is perfect. If it was, it wouldn’t be a theory. It would be a set of facts. Theories are sets of propositions that are right more often than they are wrong, but they are not infallible. However, the basic propositions of goal theory* come close to being infallible. Indeed, it is one of the strongest theories in organizational behavior.

The Basic Goal-Setting Model

Goal theory states that people will perform better if they have difficult, specific, accepted performance goals or objectives. 28 , 29 The first and most basic premise of goal theory is that people will attempt to achieve those goals that they intend to achieve. Thus, if we intend to do something (like get an A on an exam), we will exert effort to accomplish it. Without such goals, our effort at the task (studying) required to achieve the goal is less. Students whose goals are to get As study harder than students who don’t have this goal—we all know this. This doesn’t mean that people without goals are unmotivated. It simply means that people with goals are more motivated. The intensity of their motivation is greater, and they are more directed.

The second basic premise is that difficult goals result in better performance than easy goals. This does not mean that difficult goals are always achieved, but our performance will usually be better when we intend to achieve harder goals. Your goal of an A in Classical Mechanics at Cal Tech may not get you your A, but it may earn you a B+, which you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. Difficult goals cause us to exert more effort, and this almost always results in better performance.

Another premise of goal theory is that specific goals are better than vague goals. We often wonder what we need to do to be successful. Have you ever asked a professor “What do I need to do to get an A in this course?” If she responded “Do well on the exams,” you weren’t much better off for having asked. This is a vague response. Goal theory says that we perform better when we have specific goals. Had your professor told you the key thrust of the course, to turn in all the problem sets, to pay close attention to the essay questions on exams, and to aim for scores in the 90s, you would have something concrete on which to build a strategy.

A key premise of goal theory is that people must accept the goal. Usually we set our own goals. But sometimes others set goals for us. Your professor telling you your goal is to “score at least a 90 percent on your exams” doesn’t mean that you’ll accept this goal. Maybe you don’t feel you can achieve scores in the 90s. Or, you’ve heard that 90 isn’t good enough for an A in this class. This happens in work organizations quite often. Supervisors give orders that something must be done by a certain time. The employees may fully understand what is wanted, yet if they feel the order is unreasonable or impossible, they may not exert much effort to accomplish it. Thus, it is important for people to accept the goal. They need to feel that it is also their goal. If they do not, goal theory predicts that they won’t try as hard to achieve it.

Goal theory also states that people need to commit to a goal in addition to accepting it. Goal commitment is the degree to which we dedicate ourselves to achieving a goal. Goal commitment is about setting priorities. We can accept many goals (go to all classes, stay awake during classes, take lecture notes), but we often end up doing only some of them. In other words, some goals are more important than others. And we exert more effort for certain goals. This also happens frequently at work. A software analyst’s major goal may be to write a new program. Her minor goal may be to maintain previously written programs. It is minor because maintaining old programs is boring, while writing new ones is fun. Goal theory predicts that her commitment, and thus her intensity, to the major goal will be greater.

Allowing people to participate in the goal-setting process often results in higher goal commitment. This has to do with ownership. And when people participate in the process, they tend to incorporate factors they think will make the goal more interesting, challenging, and attainable. Thus, it is advisable to allow people some input into the goal-setting process. Imposing goals on them from the outside usually results in less commitment (and acceptance).

The basic goal-setting model is shown in Exhibit 14.12 . The process starts with our values. Values are our beliefs about how the world should be or act, and often include words like “should” or “ought.” We compare our present conditions against these values. For example, Randi holds the value that everyone should be a hard worker. After measuring her current work against this value, Randi concludes that she doesn’t measure up to her own value. Following this, her goal-setting process begins. Randi will set a goal that affirms her status as a hard worker. Exhibit 14.12 lists the four types of goals. Some goals are self-set. (Randi decides to word process at least 70 pages per day.) Participative goals are jointly set. (Randi goes to her supervisor, and together they set some appropriate goals for her.) In still other cases, goals are assigned. (Her boss tells her that she must word process at least 60 pages per day.) The fourth type of goal, which can be self-set, jointly determined, or assigned, is a “do your best” goal. But note this goal is vague, so it usually doesn’t result in the best performance.

Depending on the characteristics of Randi’s goals, she may or may not exert a lot of effort. For maximum effort to result, her goals should be difficult, specific, accepted, and committed to. Then, if she has sufficient ability and lack of constraints, maximum performance should occur. Examples of constraints could be that her old computer frequently breaks down or her supervisor constantly interferes.

The consequence of endeavoring to reach her goal will be that Randi will be satisfied with herself. Her behavior is consistent with her values. She’ll be even more satisfied if her supervisor praises her performance and gives her a pay increase!

In Randi’s case, her goal achievement resulted in several benefits. However, this doesn’t always happen. If goals are not achieved, people may be unhappy with themselves, and their employer may be dissatisfied as well. Such an experience can make a person reluctant to accept goals in the future. Thus, setting difficult yet attainable goals cannot be stressed enough.

Goal theory can be a tremendous motivational tool. In fact, many organizations practice effective management by using a technique called “management by objectives” (MBO). MBO is based on goal theory and is quite effective when implemented consistently with goal theory’s basic premises.

Despite its many strengths, several cautions about goal theory are appropriate. Locke has identified most of them. 30 First, setting goals in one area can lead people to neglect other areas. (Randi may word process 70 pages per day, but neglect her proofreading responsibilities.) It is important that goals be set for most major duties. Second, goal setting sometimes has unintended consequences. For example, employees set easy goals so that they look good when they achieve them. Or it causes unhealthy competition between employees. Or an employee sabotages the work of others so that only she has goal achievement.

Some managers use goal setting in unethical ways. They may manipulate employees by setting impossible goals. This enables them to criticize employees even when the employees are doing superior work and, of course, causes much stress. Goal setting should never be abused. Perhaps the key caution about goal setting is that it often results in too much focus on quantified measures of performance. Qualitative aspects of a job or task may be neglected because they aren’t easily measured. Managers must keep employees focused on the qualitative aspects of their jobs as well as the quantitative ones. Finally, setting individual goals in a teamwork environment can be counterproductive. 31 Where possible, it is preferable to have group goals in situations where employees depend on one another in the performance of their jobs.

The cautions noted here are not intended to deter you from using goal theory. We note them so that you can avoid the pitfalls. Remember, employees have a right to reasonable performance expectations and the rewards that result from performance, and organizations have a right to expect high performance levels from employees. Goal theory should be used to optimize the employment relationship. Goal theory holds that people will exert effort to accomplish goals if those goals are difficult to achieve, accepted by the individual, and specific in nature.

Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory posits that we will exert much effort to perform at high levels so that we can obtain valued outcomes. It is the motivation theory that many organizational behavior researchers find most intriguing, in no small part because it is currently also the most comprehensive theory. Expectancy theory ties together many of the concepts and hypotheses from the theories discussed earlier in this chapter. In addition, it points to factors that other theories miss. Expectancy theory has much to offer the student of management and organizational behavior.

Expectancy theory is sufficiently general that it is useful in a wide variety of situations. Choices between job offers, between working hard or not so hard, between going to work or not—virtually any set of possibilities can be addressed by expectancy theory. Basically, the theory focuses on two related issues:

- When faced with two or more alternatives, which will we select?

- Once an alternative is chosen, how motivated will we be to pursue that choice?

Expectancy theory thus focuses on the two major aspects of motivation, direction (which alternative?) and intensity (how much effort to implement the alternative?). The attractiveness of an alternative is determined by our “expectations” of what is likely to happen if we choose it. The more we believe that the alternative chosen will lead to positively valued outcomes, the greater its attractiveness to us.

Expectancy theory states that, when faced with two or more alternatives, we will select the most attractive one. And, the greater the attractiveness of the chosen alternative, the more motivated we will be to pursue it. Our natural hedonism, discussed earlier in this chapter, plays a role in this process. We are motivated to maximize desirable outcomes (a pay raise) and minimize undesirable ones (discipline). Expectancy theory goes on to state that we are also logical in our decisions about alternatives. It considers people to be rational. People evaluate alternatives in terms of their “pros and cons,” and then choose the one with the most “pros” and fewest “cons.”

The Basic Expectancy Model

The three major components of expectancy theory reflect its assumptions of hedonism and rationality: effort-performance expectancy, performance-outcome expectancy, and valences.

The effort-performance expectancy , abbreviated E1, is the perceived probability that effort will lead to performance (or E ➨ P). Performance here means anything from doing well on an exam to assembling 100 toasters a day at work. Sometimes people believe that no matter how much effort they exert, they won’t perform at a high level. They have weak E1s. Other people have strong E1s and believe the opposite—that is, that they can perform at a high level if they exert high effort. You all know students with different E1s—those who believe that if they study hard they’ll do well, and those who believe that no matter how much they study they’ll do poorly. People develop these perceptions from prior experiences with the task at hand, and from self-perceptions of their abilities. The core of the E1 concept is that people don’t always perceive a direct relationship between effort level and performance level.

The performance-outcome expectancy , E2, is the perceived relationship between performance and outcomes (or P ➨ O). 1 Many things in life happen as a function of how well we perform various tasks. E2 addresses the question “What will happen if I perform well?” Let’s say you get an A in your Classical Mechanics course at Cal Tech. You’ll be elated, your classmates may envy you, and you are now assured of that plum job at NASA. But let’s say you got a D. Whoops, that was the last straw for the dean. Now you’ve flunked out, and you’re reduced to going home to live with your parents (perish the thought!). Likewise, E2 perceptions develop in organizations, although hopefully not as drastically as your beleaguered career at Cal Tech. People with strong E2s believe that if they perform their jobs well, they’ll receive desirable outcomes—good pay increases, praise from their supervisor, and a feeling that they’re really contributing. In the same situation, people with weak E2s will have the opposite perceptions—that high performance levels don’t result in desirable outcomes and that it doesn’t really matter how well they perform their jobs as long as they don’t get fired.

Valences are the easiest of the expectancy theory concepts to describe. Valences are simply the degree to which we perceive an outcome as desirable, neutral, or undesirable. Highly desirable outcomes (a 25 percent pay increase) are positively valent. Undesirable outcomes (being disciplined) are negatively valent. Outcomes that we’re indifferent to (where you must park your car) have neutral valences. Positively and negatively valent outcomes abound in the workplace—pay increases and freezes, praise and criticism, recognition and rejection, promotions and demotions. And as you would expect, people differ dramatically in how they value these outcomes. Our needs, values, goals, and life situations affect what valence we give an outcome. Equity is another consideration we use in assigning valences. We may consider a 10 percent pay increase desirable until we find out that it was the lowest raise given in our work group.

Exhibit 14.13 summarizes the three core concepts of expectancy theory. The theory states that our perceptions about our surroundings are essentially predictions about “what leads to what.” We perceive that certain effort levels result in certain performance levels. We perceive that certain performance levels result in certain outcomes. Outcomes can be extrinsic , in that others (our supervisor) determine whether we receive them, or intrinsic , in that we determine if they are received (our sense of achievement). Each outcome has an associated valence (outcome A’s valence is V a V a ). Expectancy theory predicts that we will exert effort that results in the maximum amount of positive-valence outcomes. 2 If our E1 or E2 is weak, or if the outcomes are not sufficiently desirable, our motivation to exert effort will be low. Stated differently, an individual will be motivated to try to achieve the level of performance that results in the most rewards.

V o is the valence of the outcome. The effort level with the greatest force associated with it will be chosen by the individual.

Implications of Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory has major implications for the workplace. Basically, expectancy theory predicts that employees will be motivated to perform well on their jobs under two conditions. The first is when employees believe that a reasonable amount of effort will result in good performance. The second is when good performance is associated with positive outcomes and low performance is associated with negative outcomes. If neither of these conditions exists in the perceptions of employees, their motivation to perform will be low.

Why might an employee perceive that positive outcomes are not associated with high performance? Or that negative outcomes are not associated with low performance? That is, why would employees develop weak E2s? This happens for a number of reasons. The main one is that many organizations subscribe too strongly to a principle of equality (not to be confused with equity). They give all of their employees equal salaries for equal work, equal pay increases every year (these are known as across-the-board pay raises), and equal treatment wherever possible. Equality-focused organizations reason that some employees “getting more” than others leads to disruptive competition and feelings of inequity.

In time employees in equality-focused organizations develop weak E2s because no distinctions are made for differential outcomes. If the best and the worst salespeople are paid the same, in time they will both decide that it isn’t worth the extra effort to be a high performer. Needless to say, this is not the goal of competitive organizations and can cause the demise of the organization as it competes with other firms in today’s global marketplace.

Expectancy theory states that to maximize motivation, organizations must make outcomes contingent on performance. This is the main contribution of expectancy theory: it makes us think about how organizations should distribute outcomes. If an organization, or a supervisor, believes that treating everyone “the same” will result in satisfied and motivated employees, they will be wrong more times than not. From equity theory we know that some employees, usually the better-performing ones, will experience underreward inequity. From expectancy theory we know that employees will see no difference in outcomes for good and poor performance, so they will not have as much incentive to be good performers. Effective organizations need to actively encourage the perception that good performance leads to positive outcomes (bonuses, promotions) and that poor performance leads to negative ones (discipline, termination). Remember, there is a big difference between treating employees equally and treating them equitably.

What if an organization ties positive outcomes to high performance and negative outcomes to low performance? Employees will develop strong E2s. But will this result in highly motivated employees? The answer is maybe. We have yet to address employees’ E1s. If employees have weak E1s, they will perceive that high (or low) effort does not result in high performance and thus will not exert much effort. It is important for managers to understand that this can happen despite rewards for high performance.

Task-related abilities are probably the single biggest reason why some employees have weak E1s. Self-efficacy is our belief about whether we can successfully execute some future action or task, or achieve some result. High self-efficacy employees believe that they are likely to succeed at most or all of their job duties and responsibilities. And as you would expect, low self-efficacy employees believe the opposite. Specific self-efficacy reflects our belief in our capability to perform a specific task at a specific level of performance. If we believe that the probability of our selling $30,000 of jackrabbit slippers in one month is .90, our self-efficacy for this task is high. Specific self-efficacy is our judgment about the likelihood of successful task performance measured immediately before we expend effort on the task. As a result, specific self-efficacy is much more variable than more enduring notions of personality. Still, there is little doubt that our state-based beliefs are some of the most powerful motivators of behavior. Our efficacy expectations at a given point in time determine not only our initial decision to perform (or not) a task, but also the amount of effort we will expend and whether we will persist in the face of adversity. 32 Self-efficacy has a strong impact on the E1 factor. As a result, self-efficacy is one of the strongest determinants of performance in any particular task situation. 33

Employees develop weak E1s for two reasons. First, they don’t have sufficient resources to perform their jobs. Resources can be internal or external. Internal resources include what employees bring to the job (such as prior training, work experience, education, ability, and aptitude) and their understanding of what they need to do to be considered good performers. The second resource is called role perceptions—how employees believe their jobs are done and how they fit into the broader organization. If employees don’t know how to become good performers, they will have weak E1s. External resources include the tools, equipment, and labor necessary to perform a job. The lack of good external resources can also cause E1s to be weak.

The second reason for weak E1s is an organization’s failure to measure performance accurately. That is, performance ratings don’t correlate well with actual performance levels. How does this happen? Have you ever gotten a grade that you felt didn’t reflect how much you learned? This also happens in organizations. Why are ratings sometimes inaccurate? Supervisors, who typically give out ratings, well, they’re human. Perhaps they’re operating under the mistaken notion that similar ratings for everyone will keep the team happy. Perhaps they’re unconsciously playing favorites. Perhaps they don’t know what good and poor performance levels are. Perhaps the measurements they’re expected to use don’t fit their product/team/people. Choose one or all of these. Rating people is rarely easy.

Whatever the cause of rating errors, some employees may come to believe that no matter what they do they will never receive a high performance rating. They may in fact believe that they are excellent performers but that the performance rating system is flawed. Expectancy theory differs from most motivation theories because it highlights the need for accurate performance measurement. Organizations cannot motivate employees to perform at a high level if they cannot identify high performers.

Organizations exert tremendous influence over employee choices in their performance levels and how much effort to exert on their jobs. That is, organizations can have a major impact on the direction and intensity of employees’ motivation levels. Practical applications of expectancy theory include:

- Strengthening the effort ➨ performance expectancy by selecting employees who have the necessary abilities, providing proper training, providing experiences of success, clarifying job responsibilities, etc.

- Strengthening the performance ➨ outcome expectancy with policies that specify that desirable behavior leads to desirable outcomes and undesirable behavior leads to neutral or undesirable outcomes. Consistent enforcement of these policies is key—workers must believe in the contingencies.

- Systematically evaluating which outcomes employees value. The greater the valence of outcomes offered for a behavior, the more likely employees will commit to that alternative. By recognizing that different employees have different values and that values change over time, organizations can provide the most highly valued outcomes.

- Ensuring that effort actually translates into performance by clarifying what actions lead to performance and by appropriate training.

- Ensuring appropriate worker outcomes for performance through reward schedules (extrinsic outcomes) and appropriate job design (so the work experience itself provides intrinsic outcomes).

- Examining the level of outcomes provided to workers. Are they equitable, given the worker’s inputs? Are they equitable in comparison to the way other workers are treated?

- Measuring performance levels as accurately as possible, making sure that workers are capable of being high performers.

Managing Change

Differences in motivation across cultures.

The disgruntled employee is hardly a culturally isolated feature of business, and quitting before leaving takes the same forms, regardless of country. Cross-cultural signaling, social norms, and simple language barriers can make the task of motivation for the global manager confusing and counterintuitive. Communicating a passion for a common vision, coaching employees to see themselves as accountable and as owning their work, or attempting to create a “motivational ecosystem” can all fall flat with simple missed cues, bad translations, or tone-deaf approaches to a thousand-year-old culture.

Keeping employees motivated by making them feel valued and appreciated is not just a “Western” idea. The Ghanaian blog site Starrfmonline emphasizes that employee motivation and associated work quality improve when employees feel “valued, trusted, challenged, and supported in their work.” Conversely, when employees feel like a tool rather than a person, or feel unengaged with their work, then productivity suffers. A vicious cycle can then begin when the manager treats an employee as unmotivated and incapable, which then demotivates the employee and elicits the predicted response. The blogger cites an example from Eastern Europe where a manager sidelined an employee as inefficient and incompetent. After management coaching, the manager revisited his assessment and began working with the employee. As he worked to facilitate the employee’s efficiency and motivation, the employee went from being the lowest performer to a valuable team player. In the end, the blog says, “The very phrase ‘human resources’ frames employees as material to be deployed for organizational objectives. While the essential nature of employment contracts involves trading labour for remuneration, if we fail to see and appreciate our employees as whole people, efforts to motivate them will meet with limited success” (Starrfmonline 2017 n.p.)

Pavel Vosk, a business and management consultant based in Puyallup, Washington, says that too often, overachieving employees turn into unmotivated ones. In looking for the answer, he found that the most common source was a lack of recognition for the employee’s effort or exceptional performance. In fact, Vosk found that most employees go the extra mile only three times before they give up. Vosk’s advice is to show gratitude for employees’ effort, especially when it goes above and beyond. He says the recognition doesn’t have to be over the top, just anything that the employees will perceive as gratitude, from a catered lunch for a team working extra hours to fulfill a deadline to a simple face-to-face thank you (Huhman 2017).

Richard Frazao, president of Quaketek, based in Montreal, Quebec, stresses talking to the employees and making certain they are engaged in their jobs, citing boredom with one’s job as a major demotivating factor (Huhman 2017).

But motivating employees is not “one size fits all” globally. Rewarding and recognizing individuals and their achievements works fine in Western cultures but is undesirable in Asian cultures, which value teamwork and the collective over the individual. Whether to reward effort with a pay raise or with a job title or larger office is influenced by culture. Demoting an employee for poor performance is an effective motivator in Asian countries but is likely to result in losing an employee altogether in Western cultures. According to Matthew MacLachlan at Communicaid, “Making the assumption that your international workforce will be motivated by the same incentives can be dangerous and have a real impact on talent retention” (2016 n.p.).

Huhman, Heather R. 2017. “Employee Motivation Has to Be More Than 'a Pat on the Back.’” Entrepreneur. https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/287770

MacLachlan, Matthew. 2016. “Management Tips: How To Motivate Your International Workforce.” Communicaid. https://www.communicaid.com/cross-cultural-training/blog/motivating-international-workforce/

Starrfmonline. 2017. “HR Today: Motivating People Starts With Right Attitude.”

http://starrfmonline.com/2017/03/30/hr-today-motivating-people-starts-with-right-attitude/#

- As a Western manager working in the Middle East or sub-Saharan Africa, what motivational issues might you face?

- What problems would you expect a manager from a Confucian culture to encounter managing employees in America? In Europe?

- What regional, cultural, or ethnic issues do you think managers have to navigate within the United States?

Expectancy Theory: An Integrative Theory of Motivation

More so than any other motivation theory, expectancy theory can be tied into most concepts of what and how people become motivated. Consider the following examples.

- Need theories state that we are motivated to satisfy our needs. We positively value outcomes that satisfy unmet needs, negatively value outcomes that thwart the satisfaction of unmet needs, and assign neutral values to outcomes that do neither. In effect, the need theories explain how valences are formed.

- Operant conditioning theories state that we will probably repeat a response (behavior) in the future that was reinforced in the past (that is, followed by a positively valued consequence or the removal of a negatively valued consequence). This is the basic process involved in forming performance ➨ outcome expectancies. Both operant theories and expectancy theory argue that our interactions with our environment influence our future behavior. The primary difference is that expectancy theory explains this process in cognitive (rational) terms.

- Equity theories state that our satisfaction with a set of outcomes depends not only on how we value them but also on the circumstances surrounding their receipt. Equity theory, therefore, explains part of the process shown in Exhibit 14.11 . If we don’t feel that the outcomes we receive are equitable compared to a referent other, we will associate a lower or even negative valence with those outcomes.

- Goal theory can be integrated with the expanded expectancy model in several ways. Locke has noted that expectancy theory explains how we go about choosing a particular goal. 34 A reexamination of Exhibit 14.11 reveals other similarities between goal theory and expectancy theory. Locke’s use of the term “goal acceptance” to identify the personal adoption of a goal is similar to the “choice of an alternative” in the expectancy model. Locke’s “goal commitment,” the degree to which we commit to reaching our accepted (chosen) goal, is very much like the expectancy description of choice of effort level. Locke argues that the difficulty and specificity of a goal are major determinants of the level of performance attempted (goal-directed effort), and expectancy theory appears to be consistent with this argument (even though expectancy theory is not as explicit on this point). We can reasonably conclude that the major underlying processes explored by the two models are very similar and will seldom lead to inconsistent recommendations.

Concept Check

- Understand the process theories of motivation: operant conditioning, equity, goal, and expectancy theories.

- Describe the managerial factors managers must consider when applying motivational approaches.

- 1 Sometimes E2s are called instrumentalities, because they are the perception that performance is instrumental in getting some desired outcome.

- 2 It can also be expressed as an equation: F o r c e to Choose = E1 × ∑ ( E2 o × V o ) A level of Effort F o r c e to Choose = E1 × ∑ ( E2 o × V o ) A level of Effort Where V o V o is the valence of a given outcome (o), and E2 o E2 o is the perceived probability that a certain level of performance (e.g., Excellent, average, poor) will result in that outcome. So, for multiple outcomes, and different performance levels, the valence of the outcome and its associated performance➔outcome expectancy (E2) are multiplied and added to the analogous value for the other outcomes. Combined with the E1 (the amount of effort required to produce a level of performance), the effort level with the greatest force associated with it will be chosen by the individual.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: David S. Bright, Anastasia H. Cortes

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Management

- Publication date: Mar 20, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/14-3-process-theories-of-motivation

© Jan 9, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

Use motivation theory to inspire your team’s best work

5 frameworks for understanding the psychology behind that elusive get-up-and-go.

Get stories like this in your inbox

5-second summary

- Motivation theories explore the forces that drive people to work towards a particular outcome.

- These frameworks can help leaders who want to foster a productive environment understand the psychology behind human motivation.

- Here, we’re outlining five of the most common motivation theories and explaining how to put those theories into practice.

A huge part of a leader’s job is creating an environment where productivity thrives and teams are inspired to do their best work. But that uniquely human brand of motivation can be quite slippery – hard to understand, inspire, and harness.

An academic foundation on motivational theory can help, but opening that door exposes you to enough theoretical concepts and esoteric language to make your eyes glaze over.

This practical guide to motivation theories cuts through the jargon to help you get a solid grasp on the fundamentals that fuel your team’s peak performance – and how you can actually put these theories into action.

What is motivation theory?

Motivation theory explores the forces that drive people to work towards a particular outcome. Rather than accepting motivation as an elusive human idiosyncrasy, motivation theories offer a research-backed framework for understanding what, specifically , pushes people forward.

Motivation theory doesn’t describe one specific approach – rather, it’s an umbrella category that covers a slew of theories, each with a different take on the best “recipe” for motivation in the workplace.

CONTENT THEORIES VS. PROCESS THEORIES

At a high level, motivation theories can be split into two distinct categories: content theories and process theories .

- Content theories focus on the things that people need to feel motivated. They look at the factors that encourage and maintain motivated behaviors, like basic needs, rewards, and recognition.

- Process theories focus on individuals’ thought processes that might impact motivation, such as behavioral patterns and expectations.

5 motivation theories to inspire your team

Celebrate those little wins to keep your team motivated

A quick Google search will reveal dozens of different approaches that promise to unlock relentless ambition on your team.

It’s not likely that a single motivation theory will immediately ignite human-productivity hyperdrive. But the psychology happening behind the scenes gives unique insight into the components that influence human motivation. Leaders can then build on that foundation to create an environment that’s conducive to better focus and enthusiasm.

Let’s get into five of the most common and frequently referenced theories.

1. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

One of the most well-known motivation theories, the hierarchy of needs was published by psychologist Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “ A Theory of Human Motivation .”

The gist is that Maslow’s hierarchy outlines five tiers of human needs, commonly represented by a pyramid. These five tiers are:

- Physiological needs: Food, water, shelter, air, sleep, clothing, reproduction

- Safety needs: Personal security, employment, resources, health, property

- Love and belonging: Family, friendship, intimacy, a sense of connection

- Esteem: Status, recognition, self-esteem, respect

- Self-actualization: The ability to reach your full potential

As the term “hierarchy” implies, people tend to seek out their basic needs first (which make up the base of the pyramid). After that, they move to the needs in the next tier until they reach the tip of the pyramid.

In this same paper, however, Maslow clarifies that his hierarchy of needs isn’t quite as sequential as the pyramid framework might lead people to believe. One need doesn’t necessarily have to be fully met before the next one becomes pertinent. These human needs do build on each other, but they’re interdependent and not always consecutive. As Maslow himself said , “No need or drive can be treated as if it were isolated or discrete; every drive is related to the state of satisfaction or dissatisfaction of other drives.”

The iconic pyramid associated with Maslow’s theory wasn’t actually created by Maslow — and is even considered somewhat misleading, as you don’t need to “complete” each level before moving forward. The pyramid was popularized decades later by a different psychologist who built upon Maslow’s work along with other management theories.

Maslow’s theory was originally focused on humans’ fundamental needs generally, but in the intervening decades, it’s frequently been adapted and applied to workplaces.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in practice

The biggest lesson for leaders here is that you need to have the basics in place before anything else. Because Maslow’s tiers build on each other, a promotion won’t do much to motivate your team members if they’re concerned about the safety of their work environment.

Do your team members feel that they have some level of job security? Are they adequately paid? Do they have safe working conditions? Those are the base requirements you need to meet first.

The hierarchy of needs can support a more holistic approach to management, so you can confirm basic needs and then evolve a more nuanced idea of what people need to thrive. Do they have solid connections with you and their colleagues? Do they receive adequate recognition? Do they have some autonomy in their position?

2. Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (AKA dual-factor or two-factor theory)

Frederick Herzberg, a behavioral scientist, created the motivation-hygiene theory in 1959. The theory is a result of his interviews with a group of employees, in which he asked them two simple questions:

- Think of a time you felt good about your job. What made you feel that way?

- Think of a time you felt bad about your job. What made you feel that way?

Through those interviews, he realized that there are two mutually exclusive factors that influence employee satisfaction or dissatisfaction – hence, this theory is often called the “two-factor” or “dual-factor” theory. He named the factors:

- Hygiene encompasses basic things like working conditions, compensation, supervision, and company policies. When these nuts and bolts are in place, employee satisfaction remains steady – it’s the absence of them that moves the needle. When they’re missing, employee satisfaction decreases.

- Motivators are things like perks, recognition, and opportunity for advancement. These are the factors that, when present, increase employee motivation, productivity, and commitment.

Here’s the easiest way to think of this theory: Hygiene issues will cause dissatisfaction with your employees (and that dissatisfaction will hinder their motivation). Motivators improve satisfaction and motivation – but only when healthy hygiene is in place.

Herzberg’s theory in practice

Herzberg’s two-factor theory is often described as complementary to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as both place an emphasis on ensuring an employee’s basic needs – like security, safety, and pay – are being satisfied.

Maslow’s theory is more descriptive, and gives you a comprehensive understanding of the human needs that drive motivation. Herzberg’s theory focuses specifically on prescriptive takeaways for the workplace, giving managers a simple, two-part framework they can use to confirm the presence of hygiene factors before trying to leverage any motivators.

3. Vroom’s expectancy theory

The premise behind Vroom’s expectancy theory , established by psychologist Victor Vroom in 1964, is pretty straightforward: We make conscious choices about our behavior, and those choices are motivated by our expectations about what will happen. In other words, we make decisions to pursue pleasure and avoid pain.

The nuance lies in Vroom’s finding that people value outcomes differently. To unpack that added layer of complexity, Vroom dug a little deeper to explain two psychological processes that influence motivation:

- Instrumentality: People believe that a reward will correlate to their performance.

- Expectancy: People believe that as they increase their effort, the reward increases too.

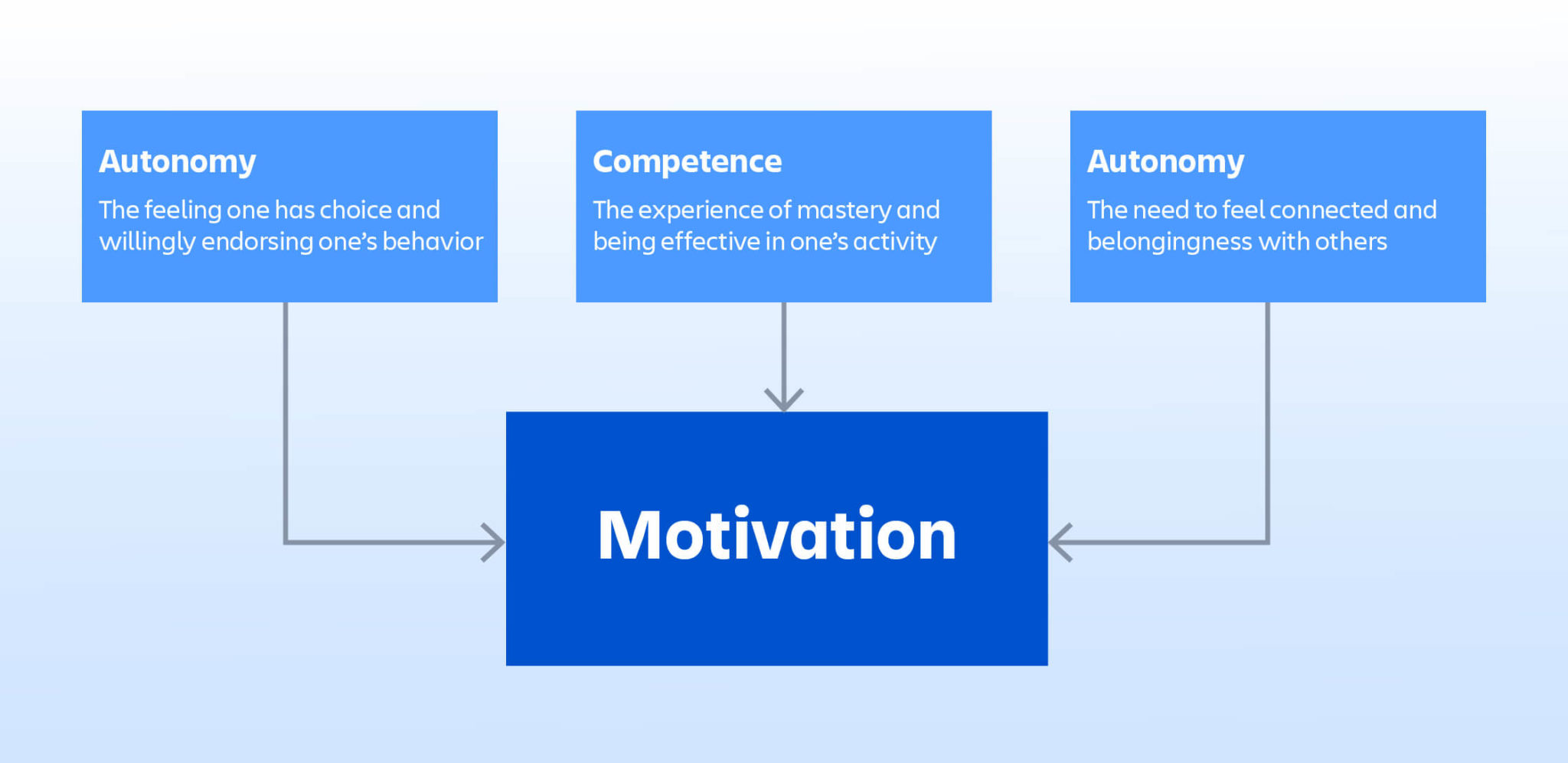

Vroom’s theory indicates that people need to be able to anticipate the outcome of their actions and behaviors. And, if you want to boost motivation, they need to care about those outcomes.