Key EBP Nursing Topics: Enhancing Patient Results through Evidence-Based Practice

This article was written in collaboration with Christine T. and ChatGPT, our little helper developed by OpenAI.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the use of the best available evidence to inform clinical decision-making in nursing. EBP has become increasingly popular in nursing practice because it ensures that patient care is based on the most current and relevant research. In this article, we will discuss the latest evidence-based practice nursing research topics, how to choose them, and where to find EBP project ideas.

What is Evidence-Based Practice Nursing?

EBP nursing involves a cyclical process of asking clinical questions, seeking the best available evidence, critically evaluating that evidence, and then integrating it with the patient’s clinical experience and values to make informed decisions. By following this process, nurses can provide the best care for their patients and ensure that their practice is informed by the latest research.

One of the key components of EBP nursing is the critical appraisal of research evidence. Nurses must be able to evaluate the quality of studies, including study design, sample size, and statistical analysis. This requires an understanding of research methodology and the ability to apply critical thinking skills to evaluate research evidence.

EBP nursing also involves the use of clinical practice guidelines and protocols, which are evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. These guidelines have been developed by expert groups and are based on the best available evidence. By following these guidelines, nurses can ensure that their practice is in line with the latest research and can provide the best possible care for their patients.

Finally, EBP nursing involves continuous professional development and a commitment to lifelong learning. Nurses must keep abreast of the latest research and clinical practice guidelines to ensure that their practice is informed by the latest research. This requires a commitment to ongoing learning and professional development, including attending conferences, reading scholarly articles, and participating in continuing education programs.

You can also learn more about evidence-based practice in nursing to gain a deeper understanding of the definition, stages, benefits, and challenges of implementing it.

Stay original!

Get 20% Discount for Plagiarism-Free and AI-Proof

How to Choose Evidence-Based Practice Nursing Research Topics

Choosing a science-based topic for nursing practice can be a daunting task, especially if you are new to the field. Here are some tips to help you choose a relevant and interesting EBP topic:

- Look for controversial or debated issues

Look for areas of nursing practice that are controversial or have conflicting evidence. These topics often have the potential to generate innovative and effective research.

- Consider ethical issues

Consider topics related to ethical issues in nursing practice. For example, bereavement care, informed consent , and patient privacy are all ethical issues that can be explored in an EBP project.

- Explore interdisciplinary topics

Nursing practice often involves collaboration with other health professionals such as physicians, social workers, and occupational therapists. Consider interdisciplinary topics that may be useful from a nursing perspective.

- Consider local or regional issues

Consider topics that are relevant to your local or regional healthcare facility. These topics may be relevant to your practice and have a greater impact on patient outcomes in your community.

- Check out the latest research

Review recent research in your area of interest to identify gaps in the literature or areas where further research is needed. This can help you develop a research question that is relevant and innovative.

With these tips in mind, you can expand your options for EBP nursing research topics and find a topic that fits your interests and goals. Remember that patient outcomes should be at the forefront of your research and choose a topic that has the potential to improve treatment and patient outcomes.

Where to Get EBP Project Ideas

There are several sources that nurses can use to get EBP project ideas. These sources are diverse and can provide valuable inspiration for research topics. By exploring these sources, nurses can find research questions that align with their interests and that address gaps in the literature. These include:

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

Look for clinical practice guidelines developed by professional organizations or healthcare institutions. These guidelines provide evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice and can help identify areas where further research is needed.

- Research databases

Explore research databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library to find the latest studies and systematic reviews. These databases can help you identify gaps in the literature and areas where further research is needed.

- Clinical Experts

Consult with clinical experts in your practice area. These experts may have insights into areas where further research is needed or may provide guidance on areas of practice that may benefit from an EBP project.

- Quality Improvement Projects

Review quality improvement projects that have been implemented in your healthcare facility. These projects may identify areas where further research is needed or identify gaps in the literature that could be addressed in an EBP project.

- Patient and family feedback

Consider patient and family feedback to identify areas where further research is needed. Patients and families can provide valuable information about areas of nursing practice that can be improved or that could benefit from further research.

Remember, when searching for ideas for EBP nursing research projects, it is important to consider the potential impact on patient care and outcomes. Select a topic that has the potential to improve patient outcomes and consider the feasibility of the project in terms of time, resources, and access to data. By choosing a topic that matches your interests and goals and is feasible at your institution, you can conduct a meaningful and productive EBP research project in nursing.

Nursing EBP Topics You Can Use in Your Essay

Here are some of the latest evidence-based practice nursing research topics that you can use in your essay or explore further in your own research:

- The impact of telehealth on patient outcomes in primary care

- The use of music therapy to manage pain in post-operative patients

- The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in reducing stress and anxiety in healthcare workers

- Combating health care-associated infections: a community-based approach

- The impact of nurse-led discharge education on readmission rates for heart failure patients

- The use of simulation in nursing education to improve patient safety

- The effectiveness of early mobilization in preventing post-operative complications

- The use of aromatherapy to manage agitation in patients with dementia

- The impact of nurse-patient communication on patient satisfaction and outcomes

- The effectiveness of peer support in improving diabetes self-management

- The impact of cultural competence training on patient outcomes in diverse healthcare settings

- The use of animal-assisted therapy in managing anxiety and depression in patients with chronic illnesses

- The effectiveness of nurse-led smoking cessation interventions in promoting smoking cessation among hospitalized patients

- Importance of literature review in evidence-based research

- The impact of nurse-led care transitions on hospital readmission rates for older adults

- The effectiveness of nurse-led weight management interventions in reducing obesity rates among children and adolescents

- The impact of medication reconciliation on medication errors and adverse drug events

- The use of mindfulness-based interventions to manage chronic pain in older adults

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in reducing hospital-acquired infections

- The impact of patient-centered care on patient satisfaction and outcomes

- The use of art therapy to manage anxiety in pediatric patients undergoing medical procedures

- Pediatric oncology: working towards better treatment through evidence-based research

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in improving medication adherence among patients with chronic illnesses

- The impact of team-based care on patient outcomes in primary care settings

- The use of music therapy to improve sleep quality in hospitalized patients

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in reducing falls in older adults

- The impact of nurse-led care on maternal and infant outcomes in low-resource settings

- The use of acupressure to manage chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in promoting breastfeeding initiation and duration

- The impact of nurse-led palliative care interventions on end-of-life care in hospice settings

- The use of hypnotherapy to manage pain in labor and delivery

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in reducing hospital length of stay for surgical patients

- The impact of nurse-led transitional care interventions on readmission rates for heart failure patients

- The use of massage therapy to manage pain in hospitalized patients

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in promoting physical activity among adults with chronic illnesses

- The impact of technology-based interventions on patient outcomes in mental health settings

- The use of mind-body interventions to manage chronic pain in patients with fibromyalgia

- Optimizing the clarifying diagnosis of stomach cancer

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in reducing medication errors in pediatric patients

- The impact of nurse-led interventions on patient outcomes in long-term care settings

- The use of aromatherapy to manage anxiety in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in improving glycemic control in patients with diabetes

- The impact of nurse-led interventions on patient outcomes in emergency department settings

- The use of relaxation techniques to manage anxiety in patients with cancer

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in improving self-management skills among patients with heart failure

- The impact of nurse-led interventions on patient outcomes in critical care settings

- The use of yoga to manage symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis

- The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions in promoting medication safety in community settings

- The impact of nurse-led interventions on patient outcomes in home healthcare settings

- The role of family involvement in the rehabilitation of stroke patients

- Assessing the effectiveness of virtual reality in pain management

- The impact of pet therapy on mental well-being in elderly patients

- Exploring the benefits of intermittent fasting on diabetic patients

- The efficacy of acupuncture in managing chronic pain in cancer patients

- Effect of laughter therapy on stress levels among healthcare professionals

- The influence of a plant-based diet on cardiovascular health

- Analyzing the outcomes of nurse-led cognitive behavioral therapy sessions for insomnia patients

- The role of yoga and meditation in managing hypertension

- Exploring the benefits of hydrotherapy in post-operative orthopedic patients

- The impact of digital health applications on patient adherence to medications

- Assessing the outcomes of art therapy in pediatric patients with chronic illnesses

- The role of nutrition education in managing obesity in pediatric patients

- Exploring the effects of nature walks on mental well-being in patients with depression

- The impact of continuous glucose monitoring systems on glycemic control in diabetic patients

The Importance of Incorporating EBP in Nursing Education

Evidence-based practice is not just a tool for seasoned nurses; it’s a foundational skill that should be integrated early into nursing education. By doing so, students learn the mechanics of nursing and the rationale behind various interventions grounded in scientific research.

- Bridging Theory and Practice:

Introducing EBP in the curriculum helps students bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice. They learn how to perform a task and why it’s done a particular way.

- Critical Thinking:

EBP promotes critical thinking. By regularly reviewing and appraising research, students develop the ability to discern the quality and applicability of studies. This skill is invaluable in a rapidly evolving field like healthcare.

- Lifelong Learning:

EBP instills a culture of continuous learning. It encourages nurses to regularly seek out the most recent research findings and adapt their practices accordingly.

- Improved Patient Outcomes:

At the heart of EBP is the goal of enhanced patient care. We ensure patients receive the most effective, up-to-date care by teaching students to base their practices on evidence.

- Professional Development:

Familiarity with EBP makes it easier for nurses to contribute to professional discussions, attend conferences, and conduct research. It elevates their professional stature and opens doors to new opportunities.

To truly prepare nursing students for the challenges of modern healthcare, it’s essential to make EBP a core part of their education.

In summary, evidence-based practice nursing is an essential component of providing quality patient care. As a nurse, it is important to stay up to date on the latest research in the field and incorporate evidence-based practices into your daily work. Choosing a research topic that aligns with your interests and addresses a gap in the literature can lead to valuable contributions to the field of nursing.

When it comes to finding EBP project ideas, there are many sources available, including professional organizations, academic journals, and healthcare conferences. By collaborating with colleagues and seeking feedback from mentors, you can refine your research question and design a study that is rigorous and relevant.

The nursing evidence-based practice topics listed above provide a starting point for further exploration and investigation. By studying the effectiveness of various nursing interventions and techniques, we can continue to improve patient outcomes and deliver better care. Ultimately, evidence-based practice nursing is about using the best available research to inform our decisions and provide the highest quality care possible to our patients.

📎 Related Articles

1. Top Nursing Research Topics for Students and Professionals 2. Nursing Debate Topics: The Importance of Discussing and Debating Nursing Issues 3. Mental Health Nursing Research Topics: Inspiring Ideas for Students 4. Top Nursing Argumentative Essay Topics: Engage in Thought-Provoking Debates 5. Top Nursing Topics for Discussion: Engaging Conversations for Healthcare Professionals 6. Exploring Controversial Issues in Nursing: Key Topics and Examples 7. Pediatric Nursing Research Topics for Students: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of content

Worried About Plagiarism?

Get 20% Off

on Plagiarism & AI Check Services!

What is Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing? (With Examples, Benefits, & Challenges)

Are you a nurse looking for ways to increase patient satisfaction, improve patient outcomes, and impact the profession? Have you found yourself caught between traditional nursing approaches and new patient care practices? Although evidence-based practices have been used for years, this concept is the focus of patient care today more than ever. Perhaps you are wondering, “What is evidence-based practice in nursing?” In this article, I will share information to help you begin understanding evidence-based practice in nursing + 10 examples about how to implement EBP.

What is Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing?

When was evidence-based practice first introduced in nursing, who introduced evidence-based practice in nursing, what is the difference between evidence-based practice in nursing and research in nursing, what are the benefits of evidence-based practice in nursing, top 5 benefits to the patient, top 5 benefits to the nurse, top 5 benefits to the healthcare organization, 10 strategies nursing schools employ to teach evidence-based practices, 1. assigning case studies:, 2. journal clubs:, 3. clinical presentations:, 4. quizzes:, 5. on-campus laboratory intensives:, 6. creating small work groups:, 7. interactive lectures:, 8. teaching research methods:, 9. requiring collaboration with a clinical preceptor:, 10. research papers:, what are the 5 main skills required for evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. critical thinking:, 2. scientific mindset:, 3. effective written and verbal communication:, 4. ability to identify knowledge gaps:, 5. ability to integrate findings into practice relevant to the patient’s problem:, what are 5 main components of evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. clinical expertise:, 2. management of patient values, circumstances, and wants when deciding to utilize evidence for patient care:, 3. practice management:, 4. decision-making:, 5. integration of best available evidence:, what are some examples of evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. elevating the head of a patient’s bed between 30 and 45 degrees, 2. implementing measures to reduce impaired skin integrity, 3. implementing techniques to improve infection control practices, 4. administering oxygen to a client with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd), 5. avoiding frequently scheduled ventilator circuit changes, 6. updating methods for bathing inpatient bedbound clients, 7. performing appropriate patient assessments before and after administering medication, 8. restricting the use of urinary catheterizations, when possible, 9. encouraging well-balanced diets as soon as possible for children with gastrointestinal symptoms, 10. implementing and educating patients about safety measures at home and in healthcare facilities, how to use evidence-based knowledge in nursing practice, step #1: assessing the patient and developing clinical questions:, step #2: finding relevant evidence to answer the clinical question:, step #3: acquire evidence and validate its relevance to the patient’s specific situation:, step #4: appraise the quality of evidence and decide whether to apply the evidence:, step #5: apply the evidence to patient care:, step #6: evaluating effectiveness of the plan:, 10 major challenges nurses face in the implementation of evidence-based practice, 1. not understanding the importance of the impact of evidence-based practice in nursing:, 2. fear of not being accepted:, 3. negative attitudes about research and evidence-based practice in nursing and its impact on patient outcomes:, 4. lack of knowledge on how to carry out research:, 5. resource constraints within a healthcare organization:, 6. work overload:, 7. inaccurate or incomplete research findings:, 8. patient demands do not align with evidence-based practices in nursing:, 9. lack of internet access while in the clinical setting:, 10. some nursing supervisors/managers may not support the concept of evidence-based nursing practices:, 12 ways nurse leaders can promote evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. be open-minded when nurses on your teams make suggestions., 2. mentor other nurses., 3. support and promote opportunities for educational growth., 4. ask for increased resources., 5. be research-oriented., 6. think of ways to make your work environment research-friendly., 7. promote ebp competency by offering strategy sessions with staff., 8. stay up-to-date about healthcare issues and research., 9. actively use information to demonstrate ebp within your team., 10. create opportunities to reinforce skills., 11. develop templates or other written tools that support evidence-based decision-making., 12. review evidence for its relevance to your organization., bonus 8 top suggestions from a nurse to improve your evidence-based practices in nursing, 1. subscribe to nursing journals., 2. offer to be involved with research studies., 3. be intentional about learning., 4. find a mentor., 5. ask questions, 6. attend nursing workshops and conferences., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. be honest with yourself about your ability to independently implement evidence-based practice in nursing., useful resources to stay up to date with evidence-based practices in nursing, professional organizations & associations, blogs/websites, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. what did nurses do before evidence-based practice, 2. how did florence nightingale use evidence-based practice, 3. what is the main limitation of evidence-based practice in nursing, 4. what are the common misconceptions about evidence-based practice in nursing, 5. are all types of nurses required to use evidence-based knowledge in their nursing practice, 6. will lack of evidence-based knowledge impact my nursing career, 7. i do not have access to research databases, how do i improve my evidence-based practice in nursing, 7. are there different levels of evidence-based practices in nursing.

• Level One: Meta-analysis of random clinical trials and experimental studies • Level Two: Quasi-experimental studies- These are focused studies used to evaluate interventions. • Level Three: Non-experimental or qualitative studies. • Level Four: Opinions of nationally recognized experts based on research. • Level Five: Opinions of individual experts based on non-research evidence such as literature reviews, case studies, organizational experiences, and personal experiences.

8. How Can I Assess My Evidence-Based Knowledge In Nursing Practice?

Understanding Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

In the ever-evolving field of healthcare, staying abreast of the latest advancements and providing optimal patient care is paramount. Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in nursing stands at the forefront of this commitment, serving as a cornerstone for modern nursing practices. By harnessing the power of current research, clinical expertise, and patient preferences, EBP ensures that nursing care is both scientifically sound and deeply personalized. This approach not only enhances patient outcomes but also empowers nurses to make informed, effective clinical decisions. Let's delve deeper into the essence of EBP and its pivotal role in transforming nursing care.

Table of contents:

What is evidence-based practice in nursing?

Why is evidence-based practice important, evidence-based practice nursing examples.

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in nursing is a method of making clinical decisions based on the best available current research, clinical expertise, and patient preferences. This approach integrates the most relevant and up-to-date scientific evidence with clinical expertise and patient values to provide the highest quality of care.

EBP follows a systematic process that includes:

- Formulating a clear clinical question from a patient’s problem.

- Searching for the best available evidence.

- Appraising the quality of the evidence.

- Applying the evidence to clinical practice.

- Evaluating the outcomes of the decision or intervention.

- Improves Patient Outcomes: EBP ensures that patient care is based on the most current and valid research , which leads to better health outcomes.

- Enhances Nursing Practices: By continually integrating new research, nursing practices remain up-to-date and effective.

- Promotes Efficient Use of Resources: EBP helps in making informed decisions about resource allocation, reducing waste, and ensuring cost-effective care.

- Empowers Nurses: Nurses who use EBP are better equipped to provide high-quality care, which can increase job satisfaction and professional development.

- Meets Regulatory and Accreditation Standards: Many healthcare organizations and accrediting bodies emphasize the use of EBP to ensure high standards of care.

- Pressure ulcer prevention example

Research has shown that using specific mattress types and regular repositioning of patients can significantly reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. By integrating these findings, nurses can create protocols to prevent pressure ulcers in at-risk patients.

- Hand hygiene practices example

EBP has demonstrated that proper hand hygiene is one of the most effective ways to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Nursing protocols now include rigorous handwashing and the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers to reduce infection rates.

- Pain management in postoperative patients example

Studies have shown that multimodal pain management approaches, which combine medications with non-pharmacological interventions (like ice packs, relaxation techniques, and physical therapy), can improve pain control. Nurses apply these strategies to manage postoperative pain more effectively.

- Fall prevention in elderly patients example

Evidence suggests that interventions such as regular exercise, home safety evaluations, and vision checks can reduce falls among the elderly. Nursing care plans often incorporate these evidence-based strategies to enhance patient safety.

- Diabetes management example

Research supports the effectiveness of self-management education and continuous glucose monitoring for patients with diabetes. Nurses play a crucial role in educating patients and implementing these practices to improve diabetes management and reduce complications.

Evidence-Based Practice in nursing is essential for providing high-quality, efficient, and patient-centered care. By integrating the best available research with clinical expertise and patient preferences, EBP enhances patient outcomes and supports continuous improvement in healthcare practices. Nurses who embrace EBP are well-positioned to lead the way in delivering innovative and effective care.

Wish you could choose your own nursing schedule? With CareRev you can.

Articles you may be interested in.

Guide to Earning Your Athletic Trainer Certification

Understanding CNA Burnout: Symptoms and Prevention

What is the Average Athletic Trainer Salary in the US?

ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

What is Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing?

5 min read • June, 01 2023

Evidence-based practice in nursing involves providing holistic, quality care based on the most up-to-date research and knowledge rather than traditional methods, advice from colleagues, or personal beliefs.

Nurses can expand their knowledge and improve their clinical practice experience by collecting, processing, and implementing research findings. Evidence-based practice focuses on what's at the heart of nursing — your patient. Learn what evidence-based practice in nursing is, why it's essential, and how to incorporate it into your daily patient care.

How to Use Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

Evidence-based practice requires you to review and assess the latest research. The knowledge gained from evidence-based research in nursing may indicate changing a standard nursing care policy in your practice Discuss your findings with your nurse manager and team before implementation. Once you've gained their support and ensured compliance with your facility's policies and procedures, merge nursing implementations based on this information with your patient's values to provide the most effective care.

You may already be using evidence-based nursing practices without knowing it. Research findings support a significant percentage of nursing practices, and ongoing studies anticipate this will continue to increase.

Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing Examples

There are various examples of evidence-based practice in nursing, such as:

- Use of oxygen to help with hypoxia and organ failure in patients with COPD

- Management of angina

- Protocols regarding alarm fatigue

- Recognition of a family member's influence on a patient's presentation of symptoms

- Noninvasive measurement of blood pressure in children

Improving patient care begins by asking how you can make it a safer, more compassionate, and personal experience.

Learn about pertinent evidence-based practice information on our Clinical Practice Material page .

Five Steps to Implement Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

Evidence-based nursing draws upon critical reasoning and judgment skills developed through experience and training. You can practice evidence-based nursing interventions by following five crucial steps that serve as guidelines for making patient care decisions. This process includes incorporating the best external evidence, your clinical expertise, and the patient's values and expectations.

- Ask a clear question about the patient's issue and determine an ultimate goal, such as improving a procedure to help their specific condition.

- Acquire the best evidence by searching relevant clinical articles from legitimate sources.

- Appraise the resources gathered to determine if the information is valid, of optimal quality compared to the evidence levels, and relevant for the patient.

- Apply the evidence to clinical practice by making decisions based on your nursing expertise and the new information.

- Assess outcomes to determine if the treatment was effective and should be considered for other patients.

Analyzing Evidence-Based Research Levels

You can compare current professional and clinical practices with new research outcomes when evaluating evidence-based research. But how do you know what's considered the best information?

Use critical thinking skills and consider levels of evidence to establish the reliability of the information when you analyze evidence-based research. These levels can help you determine how much emphasis to place on a study, report, or clinical practice guideline when making decisions about patient care.

The Levels of Evidence-Based Practice

Four primary levels of evidence come into play when you're making clinical decisions.

- Level A acquires evidence from randomized, controlled trials and is considered the most reliable.

- Level B evidence is obtained from quality-designed control trials without randomization.

- Level C typically gets implemented when there is limited information about a condition and acquires evidence from a consensus viewpoint or expert opinion.

- Level ML (multi-level) is usually applied to complex cases and gets its evidence from more than one of the other levels.

Why Is Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing Essential?

Implementing evidence-based practice in nursing bridges the theory-to-practice gap and delivers innovative patient care using the most current health care findings. The topic of evidence-based practice will likely come up throughout your nursing career. Its origins trace back to Florence Nightingale. This iconic founder of modern nursing gathered data and conclusions regarding the relationship between unsanitary conditions and failing health. Its application remains essential today.

Other Benefits of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

Besides keeping health care practices relevant and current, evidence-based practice in nursing offers a range of other benefits to you and your patients:

- Promotes positive patient outcomes

- Reduces health care costs by preventing complications

- Contributes to the growth of the science of nursing

- Allows for incorporation of new technologies into health care practice

- Increases nurse autonomy and confidence in decision-making

- Ensures relevancy of nursing practice with new interventions and care protocols

- Provides scientifically supported research to help make well-informed decisions

- Fosters shared decision-making with patients in care planning

- Enhances critical thinking

- Encourages lifelong learning

When you use the principles of evidence-based practice in nursing to make decisions about your patient's care, it results in better outcomes, higher satisfaction, and reduced costs. Implementing this method promotes lifelong learning and lets you strive for continuous quality improvement in your clinical care and nursing practice to achieve nursing excellence .

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Methods of communication, challenges of delivering primary health care, the dilemma of providing care to vulnerable populations, portrayal in media, people in the waiting room.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is firmly established as an essential component of nursing practice. Despite being present in some form in all nursing roles, its presence is arguably more prominent in professional nursing settings (RN). The RN’s responsibilities include planning patients’ care, analyzing their medical history, and administering medications (Ericksen, 2015). In addition, several managerial tasks and the duty of communicating with clinicians increase the scope of responsibilities. Most of these tasks directly determine patient outcomes depending on the quality of the made decisions. While it would be an understatement to say that practical nurses do not rely on evidence-based practices, in most cases, the outcomes of the patients are only indirectly dependent on EBP, which is the most obvious differentiation between PN and RN.

Two of the most evident methods of communication used in nursing practice are verbal and written communication. The former is used for everyday interaction with the patients, thus fulfilling their basic needs and providing counseling, education, and support necessary for improving long-term results. In both instances, the clarity and accessibility of the presented information determine the quality of care received by the patient. The written communication is responsible for providing clear instructions on treatment and healthy behaviors, thus facilitating the safety and trust of the patients. Therefore, non-native-English-speaking healthcare providers are obliged to provide oral and written translations of important documents, offer competent interpreter services, and notify the stakeholders of their right to use the services (VonBriesen, n.d.).

An environment designed for emergency medicine poses two major challenges to delivering primary health care. First, it does not offer any feasible means of continuity of care, such as access to a detailed medical history or a scheduled follow-up visit, which leads to frequent admissions for avoidable conditions. Second, the inadequately long wait times often lead to complications caused by the escalation of initially simple conditions such as high blood pressure (Leydon, 2012).

One of the challenges of patient-centered care is the disruption of balance in addressing the needs of patients with different needs. While it may seem logical to allocate more time to patients with more pressing needs and demanding conditions, it contributes to the mistreatment of populations with less apparent health risks. This eventually creates a situation where the latter have greater chances of developing adverse health conditions. Unfortunately, I cannot think of any meaningful solution to the problem aside from introducing additional regulations that ensure adequate time for both groups, although I acknowledge that such an approach may result in complications.

In order to attract viewers, the popular media often deliberately introduces inconsistencies to the portrayal of emergency rooms. First, the technical details of many procedures are commonly misrepresented, mostly to make them apparent to the viewer, with defibrillators being the most common example (MedicalBag, 2014). Second, the formal side is often diminished or neglected in favor of action scenes that resonate with the viewer, such as rushing through the corridor with the patient in an unstable condition. Third, the ethical side of the profession can be inaccurately portrayed in order to attract viewers interested in on-screen romance.

The people who enter the waiting room are characterized by the presence of an apparent health risk as well as a possibility of further complication determined by the timely delivery of care. Therefore, it would be appropriate to describe them as stressed and vulnerable.

Ericksen, K. (2015). P ractical nursing vs. professional nursing: Understanding the differences. Web.

Leydon, J. (2012). Emergency situation: The Waiting Room examines health care — and the lack of it — in America . Web.

MedicalBag. (2014). Fact or fiction: Do doctor dramas accurately portray real life in the ER? . Web.

VonBriesen. (n.d.). Health care provider’s obligations to non-English speaking patients . Web.

- Negligence as a Legal Issue in Nursing Care

- Adult Day Health Care Center: Practice Summary

- The RN to BSN: Curriculum Mapping

- Nursing: Delegation of the Re-Insertion of a Gastrointestinal Tube

- Delegation: Evidence-Based Practice Change Project

- Mental Health Nursing Skills in Practice

- Nursing Work in Different Cultures

- Legal Ramifications for Exceeding Nursing Duties

- Nursing as an Exemplary Career

- "Day of Care - 2017" Nursing Simulation Video

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 14). Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing. https://ivypanda.com/essays/evidence-based-practice-in-nursing/

"Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing." IvyPanda , 14 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/evidence-based-practice-in-nursing/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing'. 14 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing." May 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/evidence-based-practice-in-nursing/.

1. IvyPanda . "Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing." May 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/evidence-based-practice-in-nursing/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing." May 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/evidence-based-practice-in-nursing/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

How to Write an EBP Nursing Research Paper – Helpful Guide for APA Nursing Research Papers [+ 6 Examples & Outline]

Rachel andel rn, bsn.

- August 12, 2022

- Nursing Writing Guides

Writing an evidence-based practice nursing research paper is a structured process that requires extensive research and the help of the right tools and guidance. An EBP nursing research paper has different components requiring systematic research, writing, and editing.

In this guide, we provide a structured approach on how to write an effective EBP Nursing Research Paper .

How to Write an Evidence-Based Paper – Step By Step Guide for APA Nursing Research Papers

EBP Nursing Research Paper Writing

Get EBP Paper Writing Help

- Experienced and Qualified Writers

- 100% Plagiarism Free

- Timely Delivery

- 🎓 MSN & DNP – LeveL Writing

- Confidentiality and Privacy

When writing an EBP nursing research paper, it is important to consider the components of an effective nursing research paper. Here are the different elements of an EBP paper and how to write each.

Introduction to the EBP Nursing Research Papers

In an introduction, you should briefly overview the topic you will discuss. This will help your instructor understand the main points of your paper.

How do you write an introduction for an EBP Nursing Research Paper?

The introduction should be brief but provide enough information to orient readers to the topic and guide them through the rest of the paper. It should also introduce key concepts and explain what will come.

When writing your introduction, make sure it;

- Defines the problem; it answers the question

- Patient/Problem: What problems does the patient group have? What needs to be solved?

- Intervention: What intervention is being considered or evaluated? Cite appropriate literature.

- Comparison: What other interventions are possible? Cite appropriate literature.

- Outcome: What is the intended outcome of the research question?

- Introduces the key concept, thus providing a transition to the next section, which reveals that the target population

- Clearly states the purpose of the report

- Identifies the target population.

- Relates to the significance of the problem

- also relates to the significance of the problem

You should include a clear statement of the research problem at the beginning or end of the introduction. This research problem can also generate the research question used to conduct the research itself.

Here’s an EBP Nursing Research Paper example ;

(1) Root caries is a disease of humans, which manifests as lesions on the root surfaces of teeth producing loss of the natural tooth structure. (2) The lesions progress to deeper and deeper levels of the root as well as spreading laterally to enwrap it. (3) Ultimately a lesion can progress to involve the pulp, threatening the viability of the tooth resulting in pain and eventual tooth loss. (4) When located between the teeth, the lesions are difficult to acess and therefore difficult to excise and restore. (5) In otherwise healthy, North American populations, root caries lesions increase with age. (6) This report sets out to provide evidence-based guidelines on the prevention of root caries for Toronto Public Helath staff on the best available evidence. https://www.una.edu/writingcenter/docs/Writing-Resource

Working on an EBP Nursing Research Paper?

Get nursing writing help for EBP nursing research papers, capstone papers, DNP projects, and Nursing Capstone Presentations. ZERO AI, ZERO Plagiarism and 💯 Timely Delivery.

EBP Nursing Literature Review

The literature review is one of the most important sections of an EBP paper. It should provide a detailed overview of the studies conducted on your topic. You should also include any relevant quotes from these studies.

When writing an effective EBP literature review, it is important to keep in mind the following tips:

- Take the time to read all the articles you cite in your review. This will help you understand the literature better and contextualize it.

- Be sure to cite your sources correctly. If you use a journal article, for example, include the author’s last name and publication year in your citations.

- Be concise in your writing. A literature review should not exceed 10 pages in length. Try to focus on key points and highlight why they are important.

- Use analytical techniques to help you evaluate the literature. For example, consider using qualitative or quantitative methods to analyze data.

- Make sure that your writing is accessible to a broad audience. If your research is technical, explain clearly how it was conducted and what it suggests.

EBP Nursing Research Paper Methodology

The methods section should describe how you researched the topic you are writing about. You should include details about the study you chose to utilize and any statistical analysis you performed.

How to write a methodology in an EBP Nursing Research Paper

Instead of collecting data through surveys, interviews, or clinical records, as in a quantitative or qualitative study, the data you collect is the literature produced on your topic.

Remember, the research you obtain is evidence like quantitative or qualitative data. But what evidence do you select to analyze?

It can be difficult to select evidence. Don’t just go with sources that work well for you, as this will only discredit your ideas. Consider assessing the dependability of the source, ensuring you have different viewpoints when considering a change in practice.

- What database did you search?

- Which search terms did you use, and how many total articles came up with those searches?

- If the search yielded few or fewer results, that may be because the search was too narrow.

The author considers many factors when evaluating sources. Here’s how to evaluate sources for your nursing research Papers

- Assess how trustworthy the source is, how accurate it is, and whether the source has a bias.

- The credibility of study material—is the study/journal credible and original? Research can be found in scholarly journals rather than general reading material.

- Validity: Does the study measure what it says it measures? What demographic sample did the study use? A study may be invalid or inaccurate if it does not produce an accurate margin of error.

- The same test needs to be done to get a true sense of reliability and yield the same results. The test needs to end when the results have been favorable. The results of the study are valid. The report suggests high levels of consistency and validity.

Here’s How to write a Critical Analysis in Nursing

Findings – How to present findings in the EBP Nursing Research Paper

The results and discussion section should provide a detailed analysis of your findings. Discuss the implications of findings and how policymakers can use them.

Your findings will be an analysis, possibly including a chart or table. You should present the studies you selected as the most appropriate sources for studying your problem and instituting your proposed change.

Be sure to compare the following aspects of each study:

- Demographics, pools, and samples

- Methods of discovery and analysis

- Results and limitations

Remember that these studies are supposed to be the most reliable and valid ones for answering the problem you found or the practice you wish to change. Your findings should lay the groundwork for making this argument in your discussion section.

Discussion: Conclusion and Recommendations for the EBP Nursing Research Paper

The conclusion section should summarize everything that has been discussed in the paper. It should provide a summary of your findings, and make any recommendations that you have for policymakers. Be Sure to:

- Argue that the findings lead to the specific change in practice you identified in your introduction.

- Suggest a strategy for implementation. Will the change you recommend (which these studies probably also recommend) work in your situation? Why? What changes might be needed?

Here’s a video guide

Here are a few key points to remember when writing your conclusion for an EBP Research Paper. First, combine all the information and data you’ve gathered throughout your paper.

Second, summarize your study’s findings and what they mean for nursing practice. Finally, provide recommendations for future research in this area.

History of Evidence-based Practice

The history of evidence-based practice (EBP) can be traced back to the early 1990s, when the Institute of Medicine published “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System” which called for more use of evidence in health care decision making.

In 1992, the National Academies Press published “Principles of Evidence-Based Practice” which was a synthesis of work from multiple organizations and aimed to provide guidance on how to use evidence to improve patient care.

Since then, EBP has evolved into an increasingly popular approach to nursing practice. Today, EBP is used by nurses at all levels of education and experience, and it is becoming more integral to the way nurses deliver care. There are many reasons why EBP has become such an important tool in nursing practice, and this article will discuss some of them.

First, EBP helps nurses make informed decisions about patient care. Nurses need reliable information to provide quality care for their patients, and EBP provides that information by providing systematic reviews of research studies. Systematic reviews are a type of scientific literature review that systematically assess the quality and applicability of research studies in order to provide recommendations for clinical practice.

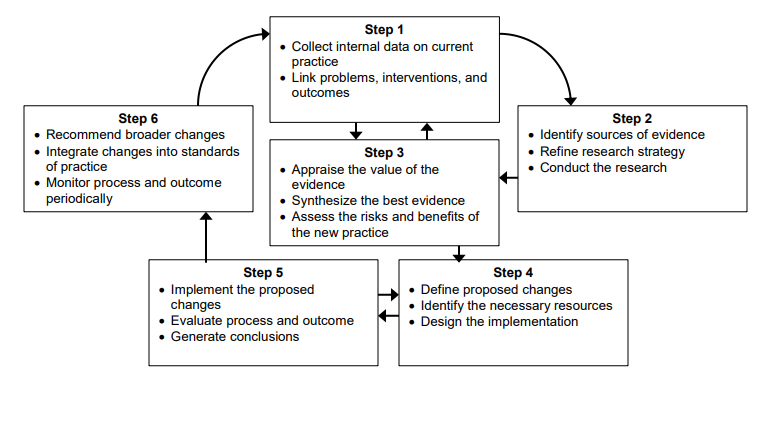

Steps of the EBP process

There are six steps in the Evidence-based Practice process:

Evidence-based practice involves the following six steps:

- Assess the need for change: Formulate the research question based on the inadequacies of current practice.- Identification of a problem or issue. Nurses should identify problems they see in their clinical practice and believe could benefit from intervention. For example, nurses may want to investigate whether patients who experience poor patient-centred outcomes after surgery have different factors, such as pain medication use or depression, that need to be addressed.

- Locate the best evidence: Obtain sources and assess their credibility and relevancy to the research question. Locate the best evidence & Synthesize evidence: Assessment of the current state of knowledge. To determine which interventions are likely to be effective, nurses should review the evidence on the effectiveness of interventions. This evidence can come from studies that have been conducted on interventions, from reviews of existing studies, or from clinical guidelines .

- 1) the target population for the intervention,

- 2) the severity of the problem or issue,

- 3) the feasibility of implementing the intervention

- 4) the cost of the intervention.

- Design the change: Apply the synthesized evidence to create a change in practice that reflects the new understanding. Selection and implementation of interventions. Nurses should select interventions that are likely effective for their target population, based on the factors listed in Step 3. They should then implement the interventions in a feasible and affordable way.

- Implement and evaluate: Apply the necessary changes and assess the changes to acquire new evidence. Evaluation of outcomes. After implementing interventions, nurses should evaluate their outcomes to determine their effectiveness. This evaluation can be done in several ways, such as through surveys or focus groups.

- Integrate and maintain changes: Reassess based on new evidence to continue improvement.

Nurses can use these steps to guide their EBP research in a number of ways. For example, they may want to investigate which interventions are most likely to be effective for a particular target population or problem, or they may want to determine which interventions are the most feasible and affordable to implement.

As you continue, nursingstudy.org/ has the top and most qualified writers to help with any of your assignments. All you need to do is place an order with us.

Find out more on

- How to write DNP capstone project Methodology Chapter

- How to write a DNP Capstone Project Literature Review

- How to write a DNP capstone project chapter 1 – Introduction

- DNP Capstone project Abstract Examples [Outline & How-to]

Evidence-Based Research Paper topics in Nursing

List of twenty EBP Nursing Research Paper ideas in nursing to write about

- Effectiveness of interventions for preventing falls in the elderly

- A pilot study of the efficacy of a home-based intervention to reduce falls in older adults

- Evaluating the effectiveness of a community-wide fall prevention intervention for older adults

- The impact of diabetes on balance and falls in older adults

- The effect of social isolation on falls in older adults

- The influence of ethnicity on falls in older adults

- Assessment and management of postural instability in the elderly

- Trends in hip fracture rates among older adults in the United States over time

- Reducing the risk factors for institutionalization among elders with Alzheimer’s disease

- Promoting healthy sleep habits among elders with dementia

- Assessing and managing sleep disturbances in elders with dementia

- Effects of exercise interventions on balance, mobility, and safety in seniors

- Rehabilitation after stroke: Targeting fall prevention

- The Effect of Nurse-Family Partnership on maternal and child health outcomes

- The Relationship of Depression to Nursing Home Use and Mortality

- Factors Influencing Patient Compliance with Diabetes Management Guidelines

- Contributions of Breastfeeding to Infant and Young Child Nutrition

- Role of the nurse in community-acquired pneumonia prevention

- Effectiveness of home health aide services on elder quality of life

- Impact of Acute Care Hospitals on the Nation’s Health

Plan of the EBP Nursing Research Paper

Writing an EBP Nursing research paper can be daunting, but it can be much easier with a plan. This guide will provide you with the essential steps you need to take to produce high-quality research papers. First, you will need to identify the problem you are researching. Next, identify the population most likely to experience the problem and/or share its consequences.

Finally, using evidence-based practices as your guide, develop a plan of action that will address the problem.

Read more on How to Format a CV for a Nursing Position Examples

Identify the Problem

The first step in writing an EBP nursing research paper is to identify the problem you are researching. This can be difficult, as the problem may be subtle or complex. However, you can use rigorous research methods to identify the problem and its consequences.

Once you have identified the problem, you must identify the population most likely to experience it and/or share its consequences. This can be a difficult task, as it may be difficult to differentiate between those affected by the problem and those not. However, by using reliable sources of information, you can develop a profile of the population that will help you identify which groups are most at risk.

Once you have identified the population most likely to experience the problem, you to develop a plan of action to address it. This action plan should be based on evidence-based practices, ensuring that your proposal is effective and efficient.

Find out more on Nursing Essay Thesis Statement [+How to & Examples]

Develop a Plan of Action

The next step in writing an EBP nursing research paper is to develop a plan of action. This action plan should be based on the evidence you have gathered and the population you have identified as most at risk.

Your action plan should include specific objectives, targets, timelines, and budgetary constraints. It should also include measures to resolve the problem, including benchmarks and measurements.

Finally, your action plan should be evaluated and revised based on stakeholder feedback. This feedback will help you ensure that your proposal is effective and efficient.

Writing an EBP nursing research paper can be daunting, but it can be much easier with a plan. This guide will provide you with the essential steps you need to take to produce high-quality research papers. First, you will need to identify the problem you are researching. Next, identify the population most likely to experience the problem and/or share its consequences. Finally, using evidence-based practices as your guide, develop a plan of action that will address the issue.

Steps of Writing an EBP Research Paper in Nursing

1. Determine the purpose of your EBP study. 2. Choose a relevant population or setting. 3. Identify the specific question you wish to answer. 4. Collect and analyze data. 5. Construct a hypothesis or theory based on your findings. 6. Write a conclusion that supports your thesis statement. 7. Offer suggestions for future research on evidence-based practice in nursing.

EBP Research Paper Literature Review Writing- Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is an approach to nursing that focuses on using evidence to guide clinical decisions. EBP is effective in improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare costs. To write an effective EBP literature review, it is important to understand the concepts of evidence and research.

The following section will provide a brief overview of the concept of evidence and its role in EBP. After this, the section will outline the different types of research used in EBP and discuss how to select appropriate research for your paper. Finally, the section will provide tips for writing an effective literature review.

You might be interested in Nursing Case Study Analysis [10 Examples & How-To Guides]

What is Evidence?

Evidence is information that supports a belief or theory. It can come from either personal experience or empirical research. Personal experience includes things like doctor’s orders or patient statements. Empirical research includes studies that use scientific methods to collect data about a particular topic.

Why Use Evidence in Nursing?

There are many reasons why using evidence in nursing is important. First, it can help improve patient outcomes. For example, using evidence-based practices when caring for patients with diabetes can help control their blood sugar levels and reduce the risk of complications.

Second, using evidence can reduce healthcare costs. For example, using evidence-based interventions when caring for patients with heart disease can help reduce the risk of death and hospitalization.

Finally, using evidence can help nurses make better decisions. For example, when caring for a patient with cancer, it is important to use evidence-based treatments that are effective in reducing the risk of cancer recurrence.

What Types of Research is Used in EBP?

There are many different types of research used in EBP. The following section will outline the different types of research and discuss how to select appropriate research for your paper.

- Clinical trials: Clinical trials are experiments that are designed to test the effectiveness of a new treatment or intervention. Clinical trials can be conducted in hospitals or clinics.

- Evaluation studies: Evaluation studies compare the outcomes of two or more treatments or interventions. Evaluation studies can be conducted in hospitals or clinics.

- Observational studies: Observational studies collect data about how people behave without Intervention. Observational studies can be conducted at home, work, or anywhere people gather data.

How to Select Appropriate Research for Your Paper

When selecting research for your EBP nursing research paper, it is important to consider the topic you are writing about and the audience you are writing for. The following tips can help you select appropriate research for your paper.

- First, consider the topic you are writing about. If you are writing about a new treatment or intervention, it is important to use clinical trials. Clinical trials are experiments that are designed to test the effectiveness of a new treatment or intervention.

- If you are writing about an existing treatment or intervention, it is important to use observational studies. Observational studies are studies that collect data about how people behave without Intervention. These studies can be conducted at home, work, or anywhere else people gather data.

- Second, consider the audience you are writing for. If you are writing for a healthcare provider, using evidence-based practices that effectively improve patient outcomes and reduce healthcare costs is essential. If you are writing for a patient or their family, using understandable and relatable information is essential.

- Finally, always check the credibility of any sources used in your paper. Credible sources will typically have references that can be verified.

Using credible sources for Evidence-based practice paper

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a nursing research methodology that draws on published, peer-reviewed scientific studies to develop rationales for and recommendations for patient care.

- It is important to use credible sources to write an EBP paper that is both credible and useful. Credible sources have been examined by experts in the field and found to be reliable. To identify credible sources, it is helpful first to understand what constitutes evidence-based practice.

- The five types of evidence considered most important in EBP are randomized clinical trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, and expert opinion.

- When using any of these types of evidence, it is important to ensure the study was conducted according to strict methodological standards.

- For example, RCTs must be blinded (i.e., the participants and investigators should not know which group is receiving the treatment being studied). Furthermore, all data collected during an RCT must be reported accurately and completely.

- Once you have identified a study as credible, the next step is to determine whether the study’s findings are relevant to your topic. It is important to note that not all studies that qualify as evidence-based practice apply to every topic.

- For example, a study that explores the use of acupuncture as a treatment for chronic neck pain would not apply to writing an EBP paper on the use of epidural analgesia in childbirth.

- Finally, it is important to consider the implications of the study’s findings when writing an EBP paper.

- For example, if a study found that a particular treatment was ineffective, it is important to discuss why this might be the case and what can be done to address the issue.

What are the 5 A’s in evidence-based practice?

Evidence-based practice is a healthcare approach that is based on the use of evidence from research studies to make decisions about care. Here are the A’s in evidence-based practice:

- Anchor: The anchor for your paper should be a specific and meaningful study that provides the basis for your argument.

- Background: State the purpose of your paper, including why you are studying the issue.

- Methods: Describe how you conducted your study and collected the data.

- Results: Discuss the findings of your study in detail, including any relevant conclusions.

- Discussion: Explain how this information can be used to improve patient care.

How do nurses write evidence based practice papers?

There are a few key steps that nurses should take when writing evidence based practice papers, including conducting research, analyzing data, and writing effective conclusions.

Here are more specific tips on how to go about each of these steps:

1. Conduct Research: The first step in writing an evidence-based practice paper is to conduct research. This means gathering information from reliable sources to support your arguments. You can find information on different types of research in the library, online databases, and journals. When selecting sources, be sure to select studies that are relevant to your topic and that you can trust.

2. Analyze Data: After you have gathered your data, it is important to analyze it carefully. This means looking at the data from different perspectives and using logic and reasoning to arrive at a conclusion. Be sure to state your findings clearly and concisely so that others can understand them.

3. Write Effective Conclusions: The final step in writing an evidence-based practice paper is to write effective conclusions. This section should summarize your findings and include any recommendations that you have for improving patient care. Remember to support your recommendations with credible evidence.

Working On an Assignment With Similar Concepts Or Instructions?

A Page will cost you $12, however, this varies with your deadline.

We have a team of expert nursing writers ready to help with your nursing assignments. They will save you time, and improve your grades.

Whatever your goals are, expect plagiarism-free works, on-time delivery, and 24/7 support from us.

Here is your 15% off to get started. Simply:

- Place your order ( Place Order )

- Click on Enter Promo Code after adding your instructions

- Insert your code – Get20

All the Best,

Have a subject expert Write for You Now

Have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, what you'll learn.

- Nursing Careers

- Nursing Paper Solutions

- Nursing Theories

- Nursing Topics and Ideas

Related Posts

- Kathleen Masters Nursing Theories: A Framework for Professional Practice

- Rural Nursing Theory: A Guide for Nursing Students

- Barbara Resnick Nursing Theory: A Comprehensive Guide for Nursing Students

Important Links

Knowledge base.

Nursingstudy.org helps students cope with college assignments and write papers on various topics. We deal with academic writing, creative writing, and non-word assignments.

All the materials from our website should be used with proper references. All the work should be used per the appropriate policies and applicable laws.

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Phone: +1 628 261 0844

Mail: [email protected]

We Accept:

@2015-2024, Nursingstudy.org

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Brechin A. Introducing critical practice. In: Brechin A, Brown H, Eby MA (eds). London: Sage/Open University; 2000

Introduction to evidence informed decision making. 2012. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45245.html (accessed 8 March 2022)

Cullen L, Adams SL. Planning for implementation of evidence-based practice. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012; 42:(4)222-230 https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e31824ccd0a

DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Ciliska D. Evidence-based nursing. A guide to clinical practice.St. Louis (MO): Mosby; 2005

Implementing evidence-informed practice: International perspectives. In: Dill K, Shera W (eds). Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press; 2012

Dufault M. Testing a collaborative research utilization model to translate best practices in pain management. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004; 1:S26-S32 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04049.x

Epstein I. Promoting harmony where there is commonly conflict: evidence-informed practice as an integrative strategy. Soc Work Health Care. 2009; 48:(3)216-231 https://doi.org/10.1080/00981380802589845

Epstein I. Reconciling evidence-based practice, evidence-informed practice, and practice-based research: the role of clinical data-mining. Social Work. 2011; 56:(3)284-288 https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/56.3.284

Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/mwpf4be4 (accessed 6 March 2022)

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006; 26:(1)13-24 https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, MacFarlane F, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in health service organisations. A systematic literature review.Malden (MA): Blackwell; 2005

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis?. BMJ. 2014; 348 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3725

Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2002; 7:36-38 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm.7.2.36

Hitch D, Nicola-Richmond K. Instructional practices for evidence-based practice with pre-registration allied health students: a review of recent research and developments. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017; 22:(4)1031-1045 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9702-9

Jerkert J. Negative mechanistic reasoning in medical intervention assessment. Theor Med Bioeth. 2015; 36:(6)425-437 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-015-9348-2

McSherry R, Artley A, Holloran J. Research awareness: an important factor for evidence-based practice?. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2006; 3:(3)103-115 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00059.x

McSherry R, Simmons M, Pearce P. An introduction to evidence-informed nursing. In: McSherry R, Simmons M, Abbott P London: Routledge; 2002

Implementing excellence in your health care organization: managing, leading and collaborating. In: McSherry R, Warr J (eds). Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2010

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Stillwell SB, Williamson KM. Evidence-based practice: step by step: the seven steps of evidence-based practice. AJN, American Journal of Nursing. 2010; 110:(1)51-53 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000366056.06605.d2

Implementing evidence-based practices: six ‘drivers’ of success. Part 3 in a Series on Fostering the Adoption of Evidence-Based Practices in Out-Of-School Time Programs. 2007. https://tinyurl.com/mu2y6ahk (accessed 8 March 2022)

Muir-Gray JA. Evidence-based healthcare. How to make health policy and management decisions.Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997

Nevo I, Slonim-Nevo V. The myth of evidence-based practice: towards evidence-informed practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2011; 41:(6)1176-1197 https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq149

Newhouse RP, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh LC, White K. The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice Rating Scale.: The Johns Hopkins Hospital: Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing; 2005

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code. 2018. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code (accessed 7 March 2022)

Nutley S, Walter I, Davies HTO. Promoting evidence-based practice: models and mechanisms from cross-sector review. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009; 19:(5)552-559 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509335496

Reed JE, Howe C, Doyle C, Bell D. Successful Healthcare Improvements From Translating Evidence in complex systems (SHIFT-Evidence): simple rules to guide practice and research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019; 31:(3)238-244 https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy160

Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH. A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999; 31:(4)317-322 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00510.x

Rubin A. Improving the teaching of evidence-based practice: introduction to the special issue. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007; 17:(5)541-547 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507300145

Shlonsky A, Mildon R. Methodological pluralism in the age of evidence-informed practice and policy. Scand J Public Health. 2014; 42:18-27 https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813516716

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009; 181:(3-4)165-168 https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.081229

Titler MG, Everett LQ. Translating research into practice. Considerations for critical care investigators. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001; 13:(4)587-604 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-5885(18)30026-1

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman V Infusing research into practice to promote quality care. Nurs Res. 1994; 43:(5)307-313 https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199409000-00009

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001; 13:(4)497-509 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-5885(18)30017-0

Ubbink DT, Guyatt GH, Vermeulen H. Framework of policy recommendations for implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Open. 2013; 3:(1) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001881

Wang LP, Jiang XL, Wang L, Wang GR, Bai YJ. Barriers to and facilitators of research utilization: a survey of registered nurses in China. PLoS One. 2013; 8:(11) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081908

Warren JI, McLaughlin M, Bardsley J, Eich J, Esche CA, Kropkowski L, Risch S. The strengths and challenges of implementing EBP in healthcare systems. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016; 13:(1)15-24 https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12149

Webber M, Carr S. Applying research evidence in social work practice: Seeing beyond paradigms. In: Webber M (ed). London: Palgrave; 2015

Evidence-based practice vs. evidence-based practice: what's the difference?. 2014. https://tinyurl.com/2p8msjaf (accessed 8 March 2022)

Evidence-informed practice: simplifying and applying the concept for nursing students and academics

Elizabeth Adjoa Kumah

Nurse Researcher, Faculty of Health and Social Care, University of Chester, Chester

View articles · Email Elizabeth Adjoa

Robert McSherry

Professor of Nursing and Practice Development, Faculty of Health and Social Care, University of Chester, Chester

View articles

Josette Bettany-Saltikov

Senior Lecturer, School of Health and Social Care, Teesside University, Middlesbrough

Paul van Schaik

Professor of Research, School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Law, Teesside University, Middlesbrough

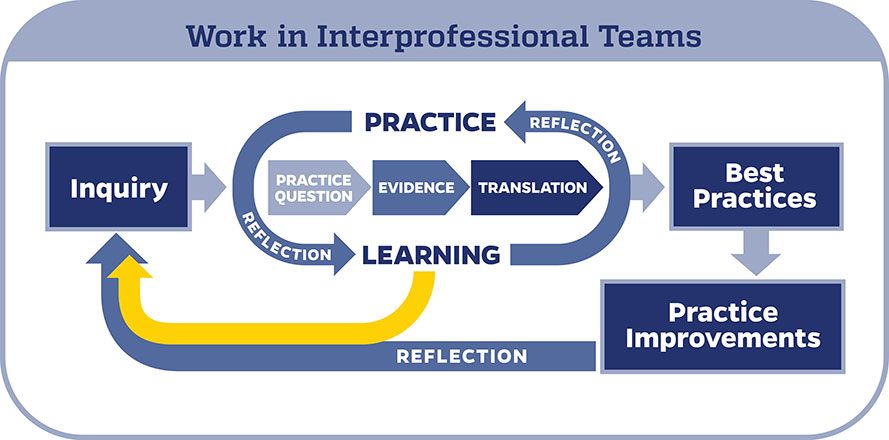

Background:

Nurses' ability to apply evidence effectively in practice is a critical factor in delivering high-quality patient care. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is recognised as the gold standard for the delivery of safe and effective person-centred care. However, decades following its inception, nurses continue to encounter difficulties in implementing EBP and, although models for its implementation offer stepwise approaches, factors, such as the context of care and its mechanistic nature, act as barriers to effective and consistent implementation. It is, therefore, imperative to find a solution to the way evidence is applied in practice. Evidence-informed practice (EIP) has been mooted as an alternative to EBP, prompting debate as to which approach better enables the transfer of evidence into practice. Although there are several EBP models and educational interventions, research on the concept of EIP is limited. This article seeks to clarify the concept of EIP and provide an integrated systems-based model of EIP for the application of evidence in clinical nursing practice, by presenting the systems and processes of the EIP model. Two scenarios are used to demonstrate the factors and elements of the EIP model and define how it facilitates the application of evidence to practice. The EIP model provides a framework to deliver clinically effective care, and the ability to justify the processes used and the service provided by referring to reliable evidence.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) was first mentioned in the literature by Muir-Gray, who defined EBP as ‘an approach to decision-making in which the clinician uses the best available evidence in consultation with the patient to decide upon the option which suits the patient best’ (1997:97). Since this initial definition was set out in 1997, EBP has gained prominence as the gold standard for the delivery of safe and effective health care.

There are several models for implementing EBP. Examples include:

Although a comprehensive review of these models is beyond the scope of this article, a brief assessment reveals some commonalities among them. These include a) asking or selecting a practice question, b) searching for the best evidence, c) critically appraising and applying the evidence, d) evaluating the outcome(s) of patient care delivery, and e) disseminating the outcome(s).