Photo by Trent Parke/Magnum

You are a network

You cannot be reduced to a body, a mind or a particular social role. an emerging theory of selfhood gets this complexity.

by Kathleen Wallace + BIO

Who am I? We all ask ourselves this question, and many like it. Is my identity determined by my DNA or am I product of how I’m raised? Can I change, and if so, how much? Is my identity just one thing, or can I have more than one? Since its beginning, philosophy has grappled with these questions, which are important to how we make choices and how we interact with the world around us. Socrates thought that self-understanding was essential to knowing how to live, and how to live well with oneself and with others. Self-determination depends on self-knowledge, on knowledge of others and of the world around you. Even forms of government are grounded in how we understand ourselves and human nature. So the question ‘Who am I?’ has far-reaching implications.

Many philosophers, at least in the West, have sought to identify the invariable or essential conditions of being a self. A widely taken approach is what’s known as a psychological continuity view of the self, where the self is a consciousness with self-awareness and personal memories. Sometimes these approaches frame the self as a combination of mind and body, as René Descartes did, or as primarily or solely consciousness. John Locke’s prince/pauper thought experiment, wherein a prince’s consciousness and all his memories are transferred into the body of a cobbler, is an illustration of the idea that personhood goes with consciousness. Philosophers have devised numerous subsequent thought experiments – involving personality transfers, split brains and teleporters – to explore the psychological approach. Contemporary philosophers in the ‘animalist’ camp are critical of the psychological approach, and argue that selves are essentially human biological organisms. ( Aristotle might also be closer to this approach than to the purely psychological.) Both psychological and animalist approaches are ‘container’ frameworks, positing the body as a container of psychological functions or the bounded location of bodily functions.

All these approaches reflect philosophers’ concern to focus on what the distinguishing or definitional characteristic of a self is, the thing that will pick out a self and nothing else, and that will identify selves as selves, regardless of their particular differences. On the psychological view, a self is a personal consciousness. On the animalist view, a self is a human organism or animal. This has tended to lead to a somewhat one-dimensional and simplified view of what a self is, leaving out social, cultural and interpersonal traits that are also distinctive of selves and are often what people would regard as central to their self-identity. Just as selves have different personal memories and self-awareness, they can have different social and interpersonal relations, cultural backgrounds and personalities. The latter are variable in their specificity, but are just as important to being a self as biology, memory and self-awareness.

Recognising the influence of these factors, some philosophers have pushed against such reductive approaches and argued for a framework that recognises the complexity and multidimensionality of persons. The network self view emerges from this trend. It began in the later 20th century and has continued in the 21st, when philosophers started to move toward a broader understanding of selves. Some philosophers propose narrative and anthropological views of selves. Communitarian and feminist philosophers argue for relational views that recognise the social embeddedness, relatedness and intersectionality of selves. According to relational views, social relations and identities are fundamental to understanding who persons are.

Social identities are traits of selves in virtue of membership in communities (local, professional, ethnic, religious, political), or in virtue of social categories (such as race, gender, class, political affiliation) or interpersonal relations (such as being a spouse, sibling, parent, friend, neighbour). These views imply that it’s not only embodiment and not only memory or consciousness of social relations but the relations themselves that also matter to who the self is. What philosophers call ‘4E views’ of cognition – for embodied, embedded, enactive and extended cognition – are also a move in the direction of a more relational, less ‘container’, view of the self. Relational views signal a paradigm shift from a reductive approach to one that seeks to recognise the complexity of the self. The network self view further develops this line of thought and says that the self is relational through and through, consisting not only of social but also physical, genetic, psychological, emotional and biological relations that together form a network self. The self also changes over time, acquiring and losing traits in virtue of new social locations and relations, even as it continues as that one self.

H ow do you self-identify? You probably have many aspects to yourself and would resist being reduced to or stereotyped as any one of them. But you might still identify yourself in terms of your heritage, ethnicity, race, religion: identities that are often prominent in identity politics. You might identify yourself in terms of other social and personal relationships and characteristics – ‘I’m Mary’s sister.’ ‘I’m a music-lover.’ ‘I’m Emily’s thesis advisor.’ ‘I’m a Chicagoan.’ Or you might identify personality characteristics: ‘I’m an extrovert’; or commitments: ‘I care about the environment.’ ‘I’m honest.’ You might identify yourself comparatively: ‘I’m the tallest person in my family’; or in terms of one’s political beliefs or affiliations: ‘I’m an independent’; or temporally: ‘I’m the person who lived down the hall from you in college,’ or ‘I’m getting married next year.’ Some of these are more important than others, some are fleeting. The point is that who you are is more complex than any one of your identities. Thinking of the self as a network is a way to conceptualise this complexity and fluidity.

Let’s take a concrete example. Consider Lindsey: she is spouse, mother, novelist, English speaker, Irish Catholic, feminist, professor of philosophy, automobile driver, psychobiological organism, introverted, fearful of heights, left-handed, carrier of Huntington’s disease (HD), resident of New York City. This is not an exhaustive set, just a selection of traits or identities. Traits are related to one another to form a network of traits. Lindsey is an inclusive network, a plurality of traits related to one another. The overall character – the integrity – of a self is constituted by the unique interrelatedness of its particular relational traits, psychobiological, social, political, cultural, linguistic and physical.

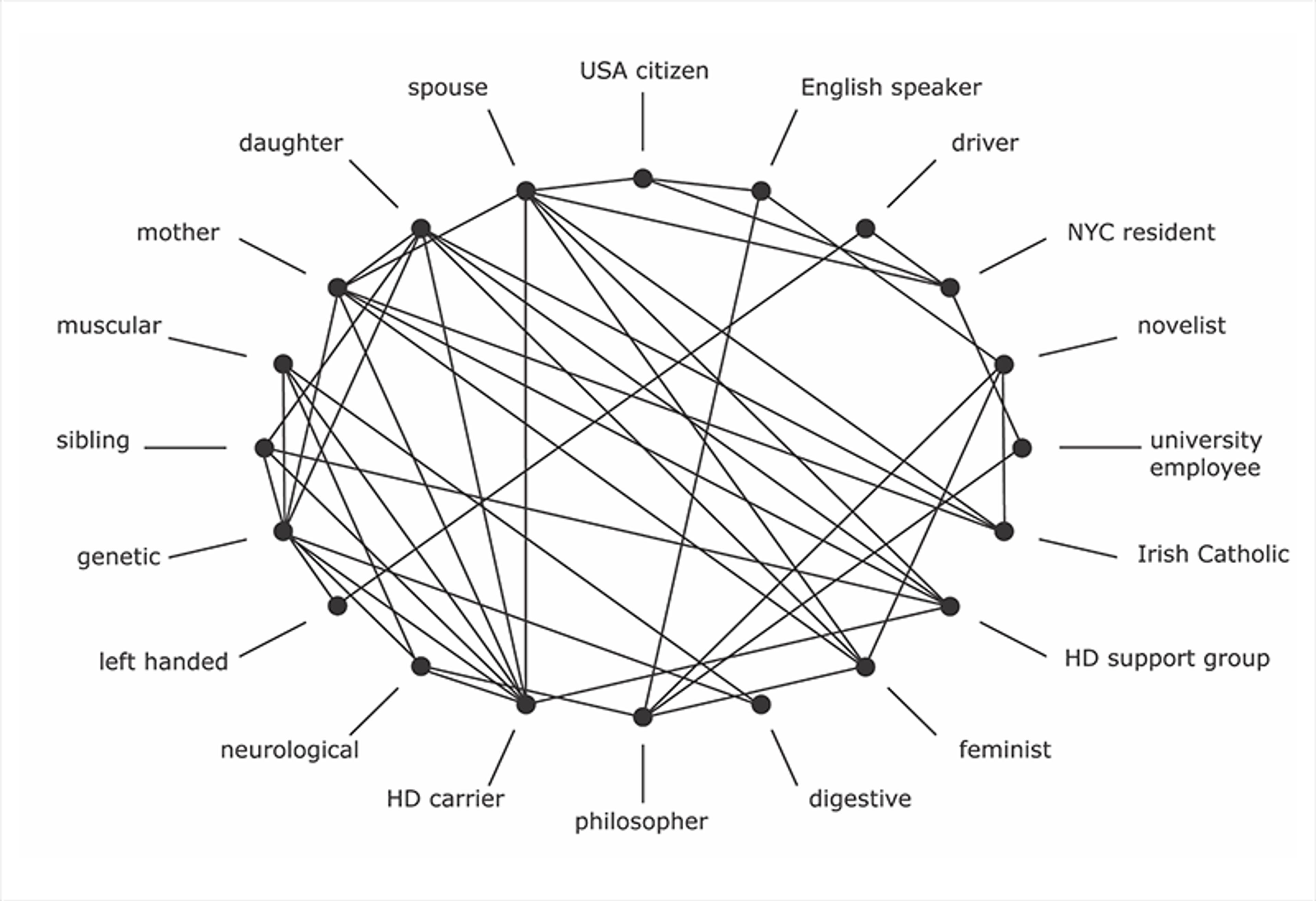

Figure 1 below is based on an approach to modelling ecological networks; the nodes represent traits, and the lines are relations between traits (without specifying the kind of relation).

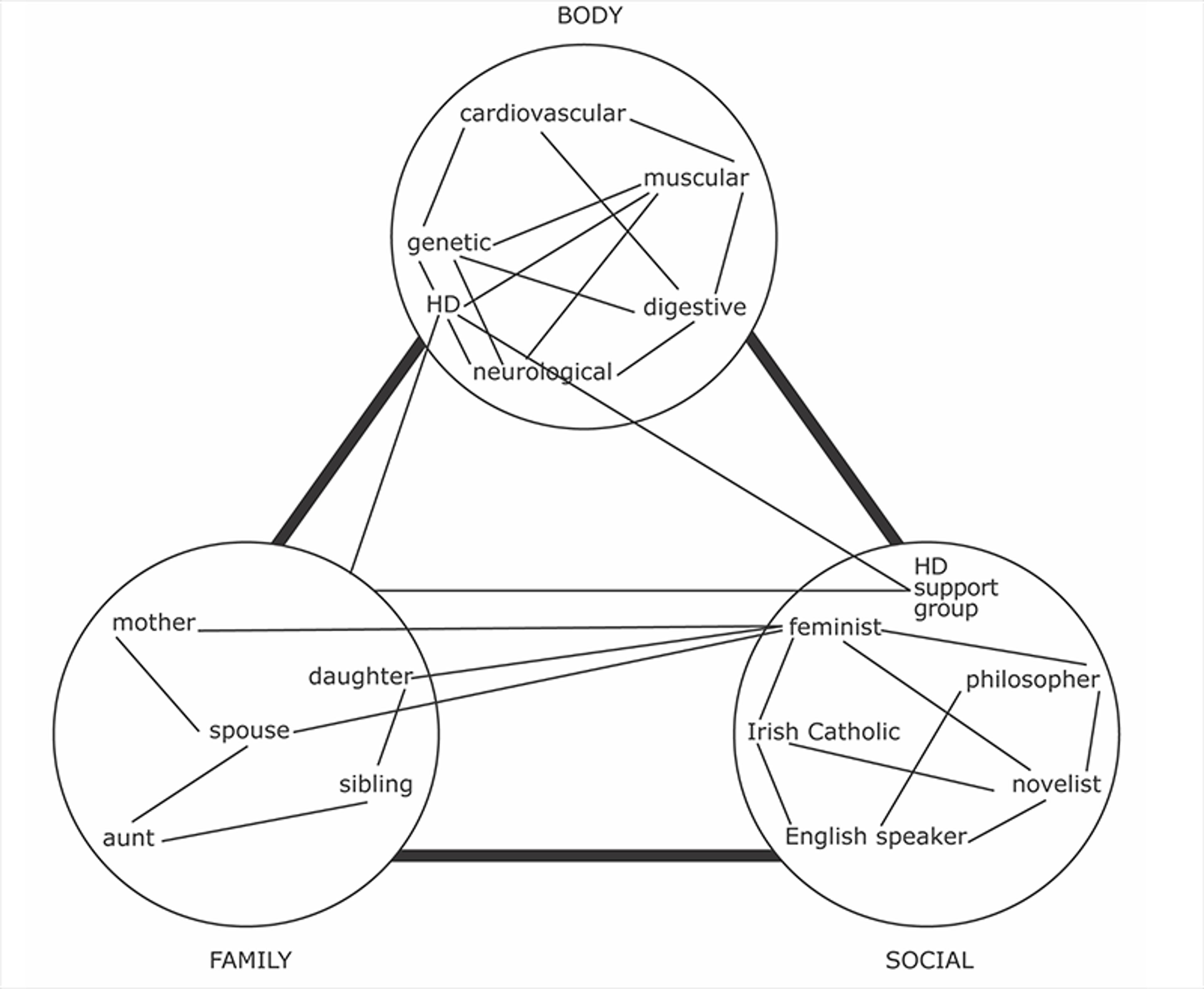

We notice right away the complex interrelatedness among Lindsey’s traits. We can also see that some traits seem to be clustered, that is, related more to some traits than to others. Just as a body is a highly complex, organised network of organismic and molecular systems, the self is a highly organised network. Traits of the self can organise into clusters or hubs, such as a body cluster, a family cluster, a social cluster. There might be other clusters, but keeping it to a few is sufficient to illustrate the idea. A second approximation, Figure 2 below, captures the clustering idea.

Figures 1 and 2 (both from my book , The Network Self ) are simplifications of the bodily, personal and social relations that make up the self. Traits can be closely clustered, but they also cross over and intersect with traits in other hubs or clusters. For instance, a genetic trait – ‘Huntington’s disease carrier’ (HD in figures 1 and 2) – is related to biological, family and social traits. If the carrier status is known, there are also psychological and social relations to other carriers and to familial and medical communities. Clusters or sub-networks are not isolated, or self-enclosed hubs, and might regroup as the self develops.

Sometimes her experience might be fractured, as when others take one of her identities as defining all of her

Some traits might be more dominant than others. Being a spouse might be strongly relevant to who Lindsey is, whereas being an aunt weakly relevant. Some traits might be more salient in some contexts than others. In Lindsey’s neighbourhood, being a parent might be more salient than being a philosopher, whereas at the university being a philosopher is more prominent.

Lindsey can have a holistic experience of her multifaceted, interconnected network identity. Sometimes, though, her experience might be fractured, as when others take one of her identities as defining all of her. Suppose that, in an employment context, she isn’t promoted, earns a lower salary or isn’t considered for a job because of her gender. Discrimination is when an identity – race, gender, ethnicity – becomes the way in which someone is identified by others, and therefore might experience herself as reduced or objectified. It is the inappropriate, arbitrary or unfair salience of a trait in a context.

Lindsey might feel conflict or tension between her identities. She might not want to be reduced to or stereotyped by any one identity. She might feel the need to dissimulate, suppress or conceal some identity, as well as associated feelings and beliefs. She might feel that some of these are not essential to who she really is. But even if some are less important than others, and some are strongly relevant to who she is and identifies as, they’re all still interconnected ways in which Lindsey is.

F igures 1 and 2 above represent the network self, Lindsey, at a cross-section of time, say at early to mid-adulthood. What about the changeableness and fluidity of the self? What about other stages of Lindsey’s life? Lindsey-at-age-five is not a spouse or a mother, and future stages of Lindsey might include different traits and relations too: she might divorce or change careers or undergo a gender identity transformation. The network self is also a process .

It might seem strange at first to think of yourself as a process. You might think that processes are just a series of events, and your self feels more substantial than that. Maybe you think of yourself as an entity that’s distinct from relations, that change is something that happens to an unchangeable core that is you. You’d be in good company if you do. There’s a long history in philosophy going back to Aristotle arguing for a distinction between a substance and its properties, between substance and relations, and between entities and events.

However, the idea that the self is a network and a process is more plausible than you might think. Paradigmatic substances, such as the body, are systems of networks that are in constant process even when we don’t see that at a macro level: cells are replaced, hair and nails grow, food is digested, cellular and molecular processes are ongoing as long as the body is alive. Consciousness or the stream of awareness itself is in constant flux. Psychological dispositions or attitudes might be subject to variation in expression and occurrence. They’re not fixed and invariable, even when they’re somewhat settled aspects of a self. Social traits evolve. For example, Lindsey-as-daughter develops and changes. Lindsey-as-mother is not only related to her current traits, but also to her own past, in how she experienced being a daughter. Many past experiences and relations have shaped how she is now. New beliefs and attitudes might be acquired and old ones revised. There’s constancy, too, as traits don’t all change at the same pace and maybe some don’t change at all. But the temporal spread, so to speak, of the self means that how a self as a whole is at any time is a cumulative upshot of what it’s been and how it’s projecting itself forward.

Anchoring and transformation, sameness and change: the cumulative network is both-and , not either-or

Rather than an underlying, unchanging substance that acquires and loses properties, we’re making a paradigm shift to seeing the self as a process, as a cumulative network with a changeable integrity. A cumulative network has structure and organisation, as many natural processes do, whether we think of biological developments, physical processes or social processes. Think of this constancy and structure as stages of the self overlapping with, or mapping on to, one another. For Lindsey, being a sibling overlaps from Lindsey-at-six to the death of the sibling; being a spouse overlaps from Lindsey-at-30 to the end of the marriage. Moreover, even if her sibling dies, or her marriage crumbles, sibling and spouse would still be traits of Lindsey’s history – a history that belongs to her and shapes the structure of the cumulative network.

If the self is its history, does that mean it can’t really change much? What about someone who wants to be liberated from her past, or from her present circumstances? Someone who emigrates or flees family and friends to start a new life or undergoes a radical transformation doesn’t cease to have been who they were. Indeed, experiences of conversion or transformation are of that self, the one who is converting, transforming, emigrating. Similarly, imagine the experience of regret or renunciation. You did something that you now regret, that you would never do again, that you feel was an expression of yourself when you were very different from who you are now. Still, regret makes sense only if you’re the person who in the past acted in some way. When you regret, renounce and apologise, you acknowledge your changed self as continuous with and owning your own past as the author of the act. Anchoring and transformation, continuity and liberation, sameness and change: the cumulative network is both-and , not either-or .

Transformation can happen to a self or it can be chosen. It can be positive or negative. It can be liberating or diminishing. Take a chosen transformation. Lindsey undergoes a gender transformation, and becomes Paul. Paul doesn’t cease to have been Lindsey, the self who experienced a mismatch between assigned gender and his own sense of self-identification, even though Paul might prefer his history as Lindsey to be a nonpublic dimension of himself. The cumulative network now known as Paul still retains many traits – biological, genetic, familial, social, psychological – of its prior configuration as Lindsey, and is shaped by the history of having been Lindsey. Or consider the immigrant. She doesn’t cease to be the self whose history includes having been a resident and citizen of another country.

T he network self is changeable but continuous as it maps on to a new phase of the self. Some traits become relevant in new ways. Some might cease to be relevant in the present while remaining part of the self’s history. There’s no prescribed path for the self. The self is a cumulative network because its history persists, even if there are many aspects of its history that a self disavows going forward or even if the way in which its history is relevant changes. Recognising that the self is a cumulative network allows us to account for why radical transformation is of a self and not, literally, a different self.

Now imagine a transformation that’s not chosen but that happens to someone: for example, to a parent with Alzheimer’s disease. They are still parent, citizen, spouse, former professor. They are still their history; they are still that person undergoing debilitating change. The same is true of the person who experiences dramatic physical change, someone such as the actor Christopher Reeve who had quadriplegia after an accident, or the physicist Stephen Hawking whose capacities were severely compromised by ALS (motor neuron disease). Each was still parent, citizen, spouse, actor/scientist and former athlete. The parent with dementia experiences loss of memory, and of psychological and cognitive capacities, a diminishment in a subset of her network. The person with quadriplegia or ALS experiences loss of motor capacities, a bodily diminishment. Each undoubtedly leads to alteration in social traits and depends on extensive support from others to sustain themselves as selves.

Sometimes people say that the person with dementia who doesn’t know themselves or others anymore isn’t really the same person that they were, or maybe isn’t even a person at all. This reflects an appeal to the psychological view – that persons are essentially consciousness. But seeing the self as a network takes a different view. The integrity of the self is broader than personal memory and consciousness. A diminished self might still have many of its traits, however that self’s history might be constituted in particular.

Plato, long before Freud, recognised that self-knowledge is a hard-won and provisional achievement

The poignant account ‘Still Gloria’ (2017) by the Canadian bioethicist Françoise Baylis of her mother’s Alzheimer’s reflects this perspective. When visiting her mother, Baylis helps to sustain the integrity of Gloria’s self even when Gloria can no longer do that for herself. But she’s still herself. Does that mean that self-knowledge isn’t important? Of course not. Gloria’s diminished capacities are a contraction of her self, and might be a version of what happens in some degree for an ageing self who experiences a weakening of capacities. And there’s a lesson here for any self: none of us is completely transparent to ourselves. This isn’t a new idea; even Plato, long before Freud, recognised that there were unconscious desires, and that self-knowledge is a hard-won and provisional achievement. The process of self-questioning and self-discovery is ongoing through life because we don’t have fixed and immutable identities: our identity is multiple, complex and fluid.

This means that others don’t know us perfectly either. When people try to fix someone’s identity as one particular characteristic, it can lead to misunderstanding, stereotyping, discrimination. Our currently polarised rhetoric seems to do just that – to lock people into narrow categories: ‘white’, ‘Black’, ‘Christian’, ‘Muslim’, ‘conservative’, ‘progressive’. But selves are much more complex and rich. Seeing ourselves as a network is a fertile way to understand our complexity. Perhaps it could even help break the rigid and reductive stereotyping that dominates current cultural and political discourse, and cultivate more productive communication. We might not understand ourselves or others perfectly, but we often have overlapping identities and perspectives. Rather than seeing our multiple identities as separating us from one another, we should see them as bases for communication and understanding, even if partial. Lindsey is a white woman philosopher. Her identity as a philosopher is shared with other philosophers (men, women, white, not white). At the same time, she might share an identity as a woman philosopher with other women philosophers whose experiences as philosophers have been shaped by being women. Sometimes communication is more difficult than others, as when some identities are ideologically rejected, or seem so different that communication can’t get off the ground. But the multiple identities of the network self provide a basis for the possibility of common ground.

How else might the network self contribute to practical, living concerns? One of the most important contributors to our sense of wellbeing is the sense of being in control of our own lives, of being self-directing. You might worry that the multiplicity of the network self means that it’s determined by other factors and can’t be self -determining. The thought might be that freedom and self-determination start with a clean slate, with a self that has no characteristics, social relations, preferences or capabilities that would predetermine it. But such a self would lack resources for giving itself direction. Such a being would be buffeted by external forces rather than realising its own potentialities and making its own choices. That would be randomness, not self-determination. In contrast, rather than limiting the self, the network view sees the multiple identities as resources for a self that’s actively setting its own direction and making choices for itself. Lindsey might prioritise career over parenthood for a period of time, she might commit to finishing her novel, setting philosophical work aside. Nothing prevents a network self from freely choosing a direction or forging new ones. Self-determination expresses the self. It’s rooted in self-understanding.

The network self view envisions an enriched self and multiple possibilities for self-determination, rather than prescribing a particular way that selves ought to be. That doesn’t mean that a self doesn’t have responsibilities to and for others. Some responsibilities might be inherited, though many are chosen. That’s part of the fabric of living with others. Selves are not only ‘networked’, that is, in social networks, but are themselves networks. By embracing the complexity and fluidity of selves, we come to a better understanding of who we are and how to live well with ourselves and with one another.

To read more about the self, visit Psyche , a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophical understanding and the arts.

Political philosophy

C L R James and America

The brilliant Trinidadian thinker is remembered as an admirer of the US but he also warned of its dark political future

Harvey Neptune

Neuroscience

The melting brain

It’s not just the planet and not just our health – the impact of a warming climate extends deep into our cortical fissures

Clayton Page Aldern

Thinkers and theories

Rawls the redeemer

For John Rawls, liberalism was more than a political project: it is the best way to fashion a life that is worthy of happiness

Alexandre Lefebvre

Anthropology

Your body is an archive

If human knowledge can disappear so easily, why have so many cultural practices survived without written records?

Helena Miton

Seeing plants anew

The stunningly complex behaviour of plants has led to a new way of thinking about our world: plant philosophy

Stella Sandford

Sex and sexuality

Sexual sensation

What makes touch on some parts of the body erotic but not others? Cutting-edge biologists are arriving at new answers

David J Linden

- About the Blog

- Cambridge University Press

- Cambridge Core

- Higher Education

- Cambridge Open Engage

Fifteen Eighty Four

Academic perspectives from cambridge university press.

- Quaternary Research

- Anthropology & Archaeology

- Behind the Scenes

- Business & Economics

- Cambridge Now

- Cambridge Reflections: Covid-19

- Climate Change

- Computer Science

- Earth & Life Sciences

- History & Classics

- Into the Intro

- Language & Linguistics

- Law & Government

- Mathematics

- Music, Theatre & Art

- Philosophy & Religion

- Science & Engineering

- Uncategorized

Thomas Aquinas – Toward a Deeper Sense of Self

Therese scarpelli cory.

“Who am I?” If Google’s autocomplete is any indication, it’s not one of the questions we commonly ask online (unlike other existential questions like “What is the meaning of life?” or “What is a human?”). But philosophers have long held that “Who am I?” is in some way the central question of human life. “Know yourself” was the inscription that the ancient Greeks inscribed over the threshold to the Delphic temple of Apollo, the god of wisdom. In fact, self-knowledge is the gateway to wisdom, as Socrates quipped: “The wise person is the one who knows what he doesn’t know.”

Thomas Aquinas

The reality is, we all lack self-knowledge to some degree, and the pursuit of self-knowledge is a lifelong quest—often a painful one. For instance, a common phenomenon studied in psychology is the “ loss of a sense of self ” that occurs when a familiar way of thinking about oneself (for example, as “a healthy person,” “someone who earns a good wage,” “a parent”) is suddenly stripped away by a major life change or tragedy. Forced to face oneself for the first time without these protective labels, one can feel as though the ground has been suddenly cut out from under one’s feet: Who am I, really?

But the reality of self-ignorance is something of a philosophical puzzle. Why do we need to work at gaining knowledge about ourselves? In other cases, ignorance results from a lack of experience. No surprise that I confuse kangaroos with wallabies: I’ve never seen either in real life. Of course I don’t know what number you’re thinking about: I can’t see inside your mind. But what excuse do I have for being ignorant of anything having to do with myself? I already am myself ! I, and I alone, can experience my own mind from the inside. This insider knowledge makes me—as communications specialists are constantly reminding us—the unchallenged authority on “what I feel” or “what I think.” So why is it a lifelong project for me to gain insight into my own thoughts, habits, impulses, reasons for acting, or the nature of the mind itself?

This is called the “problem of self-opacity,” and we’re not the only ones to puzzle over it: It was also of great interest to the medieval thinker Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), whose theory of self-knowledge is documented in my new book Aquinas on Human Self-Knowledge . It’s a common scholarly myth that early modern philosophers (starting with Descartes) invented the idea of the human being as a “self” or “subject.” My book tries to dispel that myth, showing that like philosophers and neuroscientists today, medieval thinkers were just as curious about why the mind is so intimately familiar, and yet so inaccessible, to itself. (In fact, long before Freud, medieval Latin and Islamic thinkers were speculating about a subconscious, inaccessible realm in the mind.) The more we study the medieval period, the clearer it becomes that inquiry into the self does not start with Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am.” Rather, Descartes was taking sides in a debate about self-knowledge that had already begun in the thirteenth century and earlier.

For Aquinas, we don’t encounter ourselves as isolated minds or selves, but rather always as agents interacting with our environment.

Aquinas begins his theory of self-knowledge from the claim that all our self-knowledge is dependent on our experience of the world around us. He rejects a view that was popular at the time, i.e., that the mind is “always on,” never sleeping, subconsciously self-aware in the background. Instead, Aquinas argues, our awareness of ourselves is triggered and shaped by our experiences of objects in our environment . He pictures the mind as as a sort of undetermined mental “putty” that takes shape when it is activated in knowing something. By itself, the mind is dark and formless; but in the moment of acting, it is “lit up” to itself from the inside and sees itself engaged in that act. In other words, when I long for a cup of mid-afternoon coffee, I’m not just aware of the coffee, but of myself as the one wanting it . So for Aquinas, we don’t encounter ourselves as isolated minds or selves, but rather always as agents interacting with our environment. That’s why the labels we apply to ourselves—“a gardener,” “a patient person,” or “a coffee-lover”—are always taken from what we do or feel or think toward other things.

The Temple of Apollo at Delphi, © 2004 David Monniaux

But if we “see” ourselves from the inside at the moment of acting, what about the “problem of self-opacity” mentioned above? Instead of lacking self-knowledge, shouldn’t we be able to “see” everything about ourselves clearly? Aquinas’s answer is that just because we experience something doesn’t mean we instantly understand everything about it—or to use his terminology: experiencing that something exists doesn’t tell us what it is . (By comparison: If someday I encounter a wallaby, that won’t make me an expert about wallabies.) Learning about a thing’s nature requires a long process of gathering evidence and drawing conclusions, and even then we may never fully understand it. The same applies to the mind. I am absolutely certain, with an insider’s perspective that no one else can have, of the reality of my experience of wanting another cup of coffee. But the significance of those experiences—what they are, what they tell me about myself and the nature of the mind—requires further experience and reasoning. Am I hooked on caffeine? What is a “desire” and why do we have desires? These questions can only be answered by reasoning about the evidence taken from many experiences.

Aquinas, then, would surely approve that we’re not drawn to search online for answers to the question, “Who am I?” That question can only be answered “from the inside” by me , the one asking the question. At the same time, answering this question isn’t a matter of withdrawing from the world and turning in on ourselves. It’s a matter of becoming more aware of ourselves at the moment of engaging with reality, and drawing conclusions about what our activities towards other things “say” about us. There’s Aquinas’s “prescription” for a deeper sense of self.

Enjoyed reading this article? Share it today:

About The Author

Therese Scarpelli Cory is the author of Aquinas on Human Self-Knowledge. She is assistant professor of philosophy at Seattle University....

Find more articles like this:

The Martyr’s Many Faces

The quest for the essence of Christianity is alive and well

Find a subject, view by year, join the conversation.

Keep up with the latest from Cambridge University Press on our social media accounts.

Latest Comments

Have your say!

- Relationships

A New Integrative Model of the Self

The self emerges as animals model themselves across time and in relationships..

Posted September 30, 2021 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- Why Relationships Matter

- Take our Relationship Satisfaction Test

- Find a therapist to strengthen relationships

- Research and scholarship on the nature of the self have yielded conflicting messages, but a new model helps frame the self in a coherent way.

- The model suggests that the self emerges as animals model themselves over time in different contexts and relationships.

- The human self consists of a nonverbal experiential self, a narrating ego, and a persona that manages impressions.

The post was co-authored by John Vervaeke and Christopher Mastropietro.

What is the self? Is it the core essence that defines what and who we truly are? Or is it an egoic illusion that we fallaciously cling to and, to be healthy and mature, we must learn to become detached from? Many voices in psychology and education teach us to be our true selves or be true to our core self. And yet other traditions, such as Buddhism, seem to argue that there is no such thing as the self. Research and scholarship on the nature of the self have yielded similar confusions and conflicting messages. Consider the tensions between the following quotes from two well-known psychologists:

"Properly speaking, a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their head." — William James

"But the concept of the self loses its meaning if a person has multiple selves … the essence of self involves integration of diverse experiences into a unity … In short, unity is one of the defining features of selfhood and identity ." — Roy Baumeister

The self, alongside concepts like behavior, mind, cognition , and consciousness, represents one of the most central but also most elusive concepts in psychology and cognitive science. However, recent work on developing metatheoretical synergies optimistically point to the possibility of a coherent articulation of what the self is in a way that is consistent with the best current research, the focus and concerns of therapists, and the deep existential reflections given by philosophical perspectives that reflect on how we relate to ourselves and our place in the cosmos.

A New Model for Framing the Self

Earlier this year, John Vervaeke produced an educational video series, " The Elusive “I”: On the Nature and Function of the Self ," that tackled these questions and generated a new model for framing the self. The series built from an earlier exploration into the tangled knot of consciousness that blended some of the best metatheories in psychology (i.e., Henriques’ Unified Theory) and cognitive science (i.e., Vervaeke’s Recursive Relevance Realization ) to generate a clear, holistic picture of how subjective conscious experience emerges in the animal-mental plane of existence.

That series identified two broad steps in the evolution of animal consciousness. First, perhaps as early as the Cambrian Explosion some 520 million years ago, there was an integration in the brain of sensory inputs with inner drives that functioned to generate “valence qualia,” which are bodily feeling states like pleasure and pain that guide animals toward and away from valued stimuli. Then, as animals advanced in their capacity to model the environment and their anticipated outcomes, and deliberate based on possible action sequences, a more extended form of subjective consciousness emerged, something we might call “an inner mind’s eye” that arises in a global neuronal workspace. As was described in the series, this inner mind’s eye can be effectively divided into a witness function that frames and indexes specific aspects of attention with a hereness-nowness-togetherness binding that can be called “adverbial qualia,” and the contents of that frame, such as the redness of an apple, which can be called “adjectival qualia.”

A Need to Model the Self Across Time

It turns out that this model of animal consciousness has crucial implications for the emergence of a sense of self. Work in robotics over the past several decades has demonstrated that any complex adaptive system that can move with efficiency must simultaneously model not just the exterior environment but also account for the interior movements and positions of the robot. Put simply, coordinating agent-arena actions require models of both the agent and arena and their dynamic relation. This is true of both robots and animals.

If this fact is coupled to the idea that higher forms of cognition and consciousness allow animals to extend themselves across time and situations, we move from modeling the immediate agent-arena relationship to modeling the agent across many separate arenas that are extended in time. For example, a rat at a choice point in a maze will project itself down the right arm of the maze, and then down the left arm. Crucially, although the rat’s simulation of the two paths will be different, the deliberation requires a consistent model of the self (i.e., the rat is the same, whereas the paths are what differ). This insight gives rise to the claim that as animals engage in deliberation across time, a model of the self that is distinct from the many possible environments is required. The point here is that the jump in cognition and consciousness that allows animals to extend themselves across time also points to the need for a more elaborate model of the self.

Modeling the Self in Relation to Others

The series argued that a second crucial jump would occur as animals became increasingly intertwined in relationships with others. Consider, for example, parental care and the attachments formed with offspring. In such relationships, the caregiver must not only model their own actions and place across time but also model the needs of the other. Moreover, they are in dynamic participatory relation with each other across time. Attachment theory shows how this dance between caregiver and young is enacted and can lead to either a secure relational holding environment or not.

This process of modeling self-in-relation-to-other is framed by Vervaeke by adding “relational” to recursive relevance realization. That is, it is the self-other feedback loop that should be tracked for relevant information. This formulation is directly aligned with Henriques’ Influence Matrix, which maps the process dimensions of the human primate relationship system. Specifically, it suggests that humans intuitively track processes of exchange for indications of having social influence or being valued by others, as well as implications for power/ competition , love/affiliation, and levels of dependency or independence.

Consistent with work from Tomasello, humans have particularly strong capacities among the great apes to track others' perspectives and feelings, and develop a shared attention and intention. Tomasello calls this the intersubjective “we” space that can form as humans sync up with others. Following the logic above, this suggests massive mapping of self across time in relationship to many others and in many contexts. The result is a dynamic picture of the human primate, pre-verbal self that is very consistent with both James’ assertion that the self is a function of the other and Baumeister’s claim that there is a felt sense of unity.

The Justifying Ego

Of course, as humans evolved over the past 200,000 years, we have moved from implicit intersubjective coordination to explicit intersubjectivity, via the emergence of symbolic language and the development of justification systems that function to generate a shared propositional field of what is and ought to be. Henriques’ work on the Unified Theory shows how the problems and processes of justification set the stage for the evolution of the human ego as the mental organ of justification and help explain the relationship between the ego, the primate experiential self, and the persona, which is the public image or face or mask that people project to manage status and maintain favorable impressions.

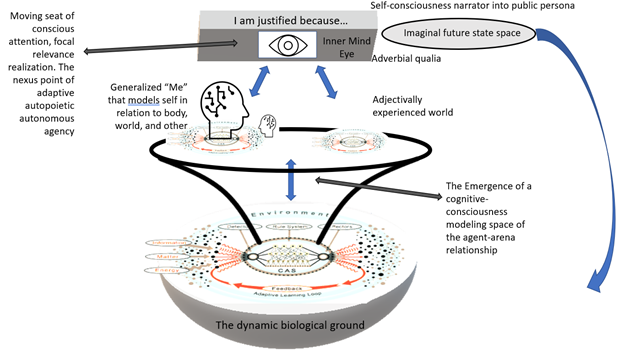

The diagram below provides a map of the insights generated by the series. It depicts how layers of cognitive modeling emerge that function to generate models of both the world and the “Generalized Me” that models the self across time. It also places that in relationship to human consciousness via the inner mind’s eye that functions as the adverbial qualia framing of the adjectivally experienced properties. On top of that primate self in humans is the justifying ego that manages the “legitimacy of the self” on the culture-person plane of existence.

After elaborating on the cognitive science that grounds the model, the series shifted into the world of clinical psychology and explored how many neurotic conditions can be understood as arising from the conflicts between a core, emotionally charged experiential self, a justifying ego, and a persona on the social stage. Consistent with this frame, both humanistic and psychodynamic approaches are structured to identify these conflicts and bring insight and acceptance in a way that affords a more coherent, integrated identity. The last part of the series shifted to existential concerns, drawing on insights from Kierkegaard and other philosophers to show how the above model of the self is consistent with and can ground and inform intrapersonal and interpersonal dialogical reflections on how we relate to ourselves and our place in the cosmos.

The Elusive "I" Episode 1, Problematizing the Self

The Elusive "I" Episode 2, Problematizing the Self Part II

The Elusive "I" Episode 3, The Social and Developmental Aspects

The Elusive "I" Episode 4, The Self and Recursive Relevance Realization

The Elusive "I" Episode 5, A Naturalistic Account of Self and Personhood

The Elusive "I" Episode 6, Existential Concerns

The Elusive "I" Episode 7, Psychedelic and Mystical Experiences

The Elusive "I" Episode 8, Connecting the Dots with Predictive Processing

The Elusive "I" Episode 9, A Unified Clinical View of the Self

The Elusive "I" Episode 10, The Self, the Ego, and the Persona

The Elusive "I" Episode 11, The Existential-Spiritual Dimension of the Self

The Elusive "I" Episode 12, The Self, Soul and Spirit

Commentary: An "I" for the Elusive I (Bruce Alderman and Layman Pascal; Integral Stage)

Dialogical Reflections on the Elusive I (Vervaeke, Henriques, Mastropietro, Alderman and Pascal)

Gregg Henriques, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology at James Madison University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

“i” and “me”: the self in the context of consciousness.

- Cognition and Philosophy Lab, Department of Philosophy, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

James (1890) distinguished two understandings of the self, the self as “Me” and the self as “I”. This distinction has recently regained popularity in cognitive science, especially in the context of experimental studies on the underpinnings of the phenomenal self. The goal of this paper is to take a step back from cognitive science and attempt to precisely distinguish between “Me” and “I” in the context of consciousness. This distinction was originally based on the idea that the former (“Me”) corresponds to the self as an object of experience (self as object), while the latter (“I”) reflects the self as a subject of experience (self as subject). I will argue that in most of the cases (arguably all) this distinction maps onto the distinction between the phenomenal self (reflecting self-related content of consciousness) and the metaphysical self (representing the problem of subjectivity of all conscious experience), and as such these two issues should be investigated separately using fundamentally different methodologies. Moreover, by referring to Metzinger’s (2018) theory of phenomenal self-models, I will argue that what is usually investigated as the phenomenal-“I” [following understanding of self-as-subject introduced by Wittgenstein (1958) ] can be interpreted as object, rather than subject of experience, and as such can be understood as an element of the hierarchical structure of the phenomenal self-model. This understanding relates to recent predictive coding and free energy theories of the self and bodily self discussed in cognitive neuroscience and philosophy.

Introduction

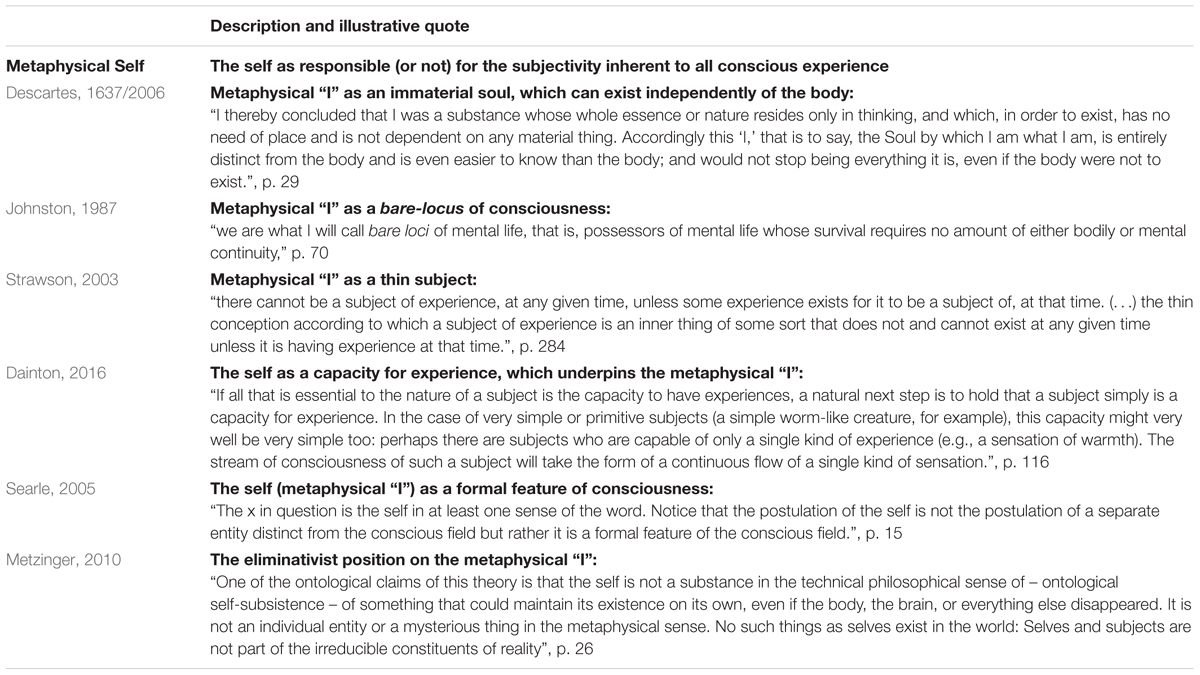

Almost 130 years ago, James (1890) introduced the distinction between “Me” and “I” (see Table 1 for illustrative quotes) to the debate about the self. The former term refers to understanding of the self as an object of experience, while the latter to the self as a subject of experience 1 . This distinction, in different forms, has recently regained popularity in cognitive science (e.g., Christoff et al., 2011 ; Liang, 2014 ; Sui and Gu, 2017 ; Truong and Todd, 2017 ) and provides a useful tool for clarifying what one means when one speaks about the self. However, its exact meaning varies in cognitive science, especially in regard to what one understands as the self as subject, or “I.”

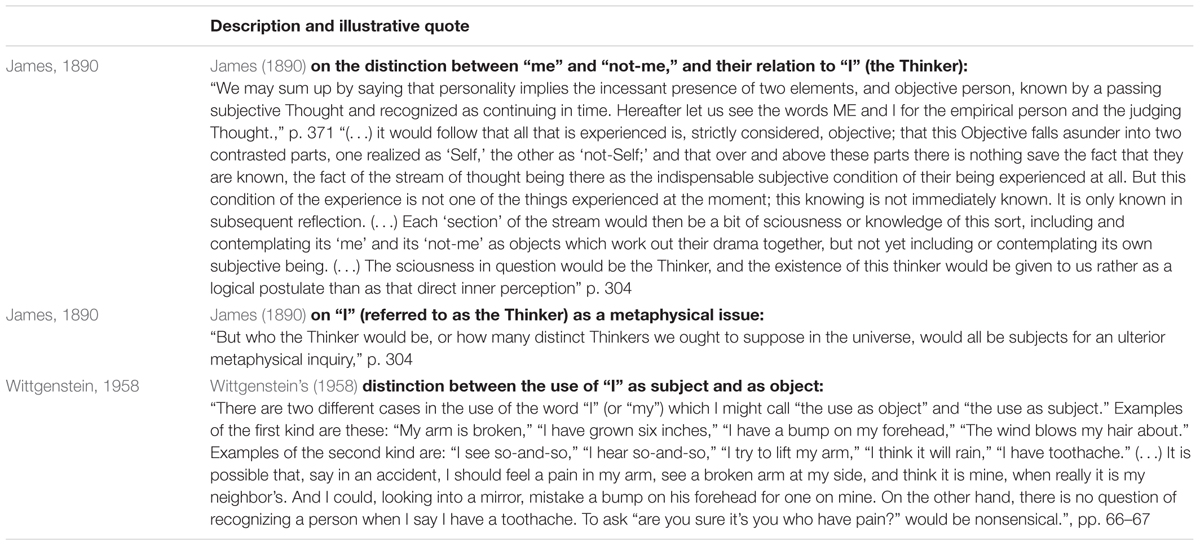

TABLE 1. Quotes from James (1890) illustrating the distinction between self-as-object (“Me”) and self-as-subject (“I”) and a quote from Wittgenstein (1958) illustrating his distinction between the use of “I” as object and as subject.

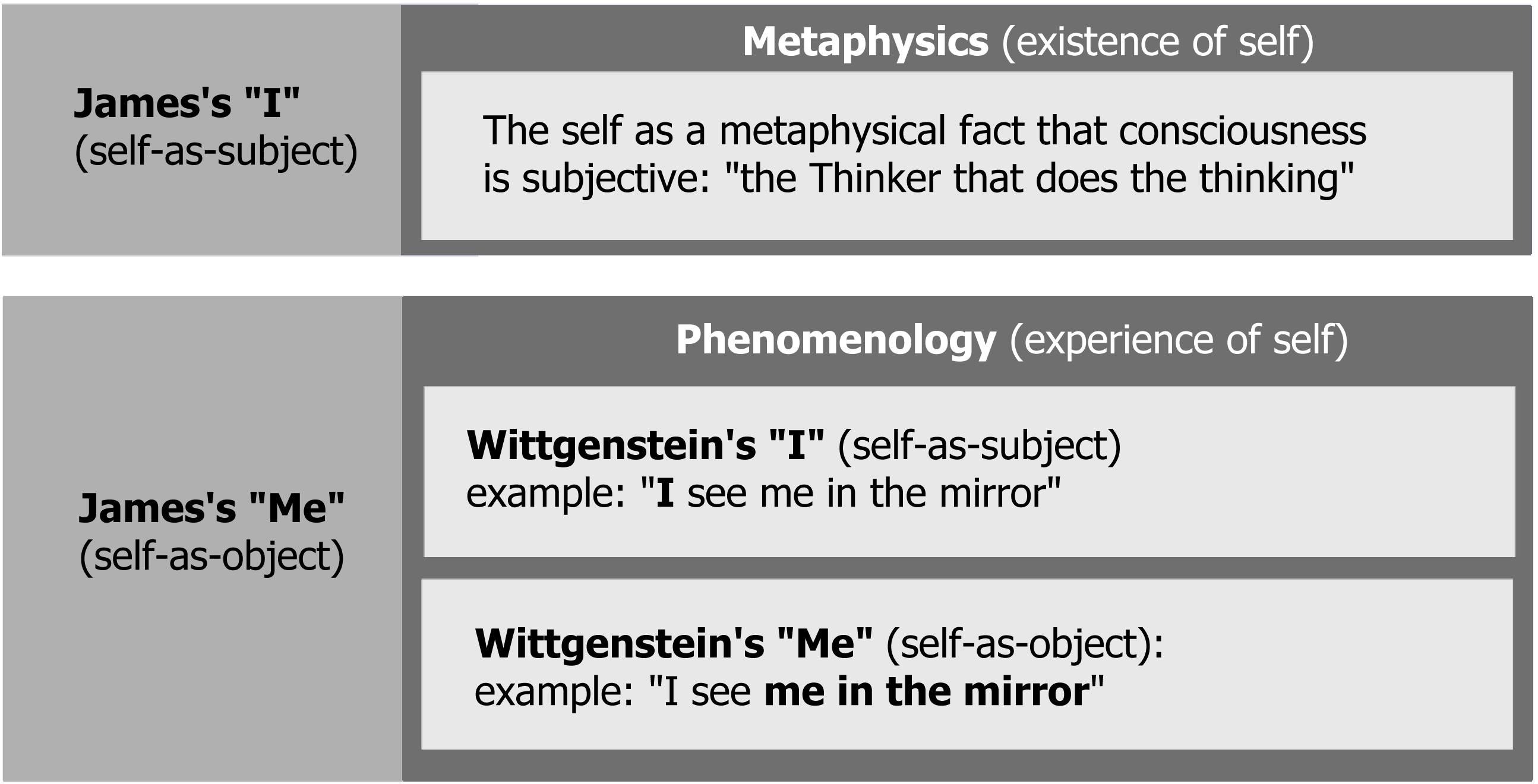

The goal of this paper is to take a step back from cognitive science and take a closer look at the conceptual distinction between “Me” and “I” in the context of consciousness. I will suggest, following James (1890) and in opposition to the tradition started by Wittgenstein (1958) , that in this context “Me” (i.e., the self as object) reflects the phenomenology of selfhood, and corresponds to what is also known as sense of self, self-consciousness, or phenomenal selfhood (e.g., Blanke and Metzinger, 2009 ; Blanke, 2012 ; Dainton, 2016 ). On the other hand, the ultimate meaning of “I” (i.e., the self as subject) is rooted in metaphysics of subjectivity, and refers to the question: why is all conscious experience subjective and who/what is the subject of conscious experience? I will argue that these two theoretical problems, i.e., phenomenology of selfhood and metaphysics of subjectivity, are in principle independent issues and should not be confused. However, cognitive science usually follows the Wittgensteinian tradition 2 by understanding the self-as-subject, or “I,” as a phenomenological, rather than metaphysical problem [Figure 1 illustrates the difference between James (1890) and Wittgenstein’s (1958) approach to the self]. By following Metzinger’s (2003 , 2010 ) framework of phenomenal self-models, and in agreement with a reductionist approach to the phenomenal “I” 3 ( Prinz, 2012 ), I will argue that what is typically investigated in cognitive science as the phenomenal “I” [or the Wittgenstein’s (1958) self-as-subject] can be understood as just a higher-order component of the self-model reflecting the phenomenal “Me.” Table 2 presents some of crucial claims of the theory of self-models, together with concise references to other theories of the self-as-object discussed in this paper.

FIGURE 1. An illustration of James (1890) and Wittgenstein’s (1958) distinctions between self-as-object (“Me”) and self-as-subject (“I”). In the original formulation, James’ (1890) “Me” includes also physical objects and people (material and social “Me”) – they were not included in the picture, because they are not directly related to consciousness.

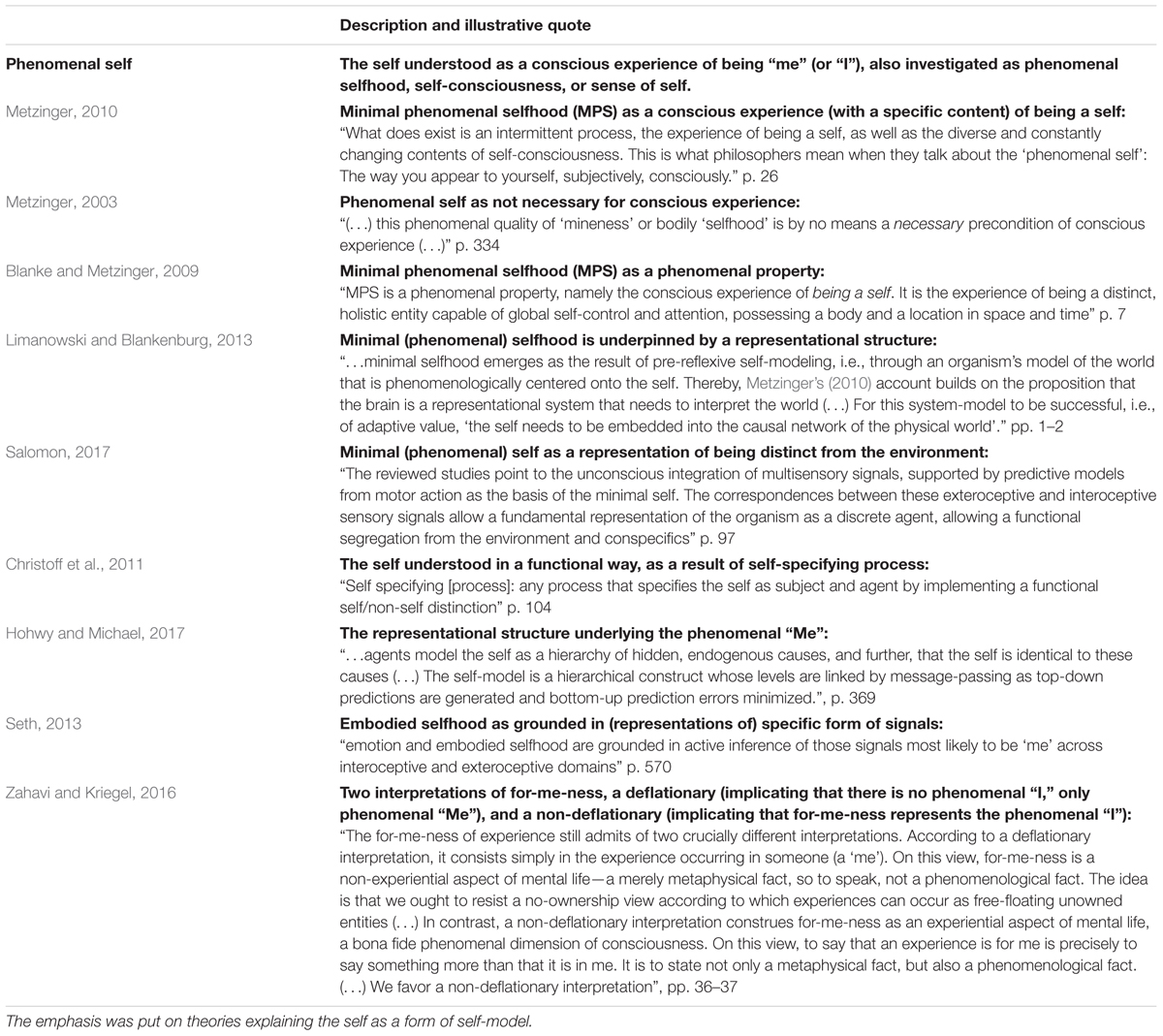

TABLE 2. Examples of theories of the self-as-object (“Me”) in the context of consciousness, as theories of the phenomenal self, with representative quotes illustrating each position.

“Me” As An Object Of Experience: Phenomenology Of Self-Consciousness

The words ME, then, and SELF, so far as they arouse feeling and connote emotional worth, are OBJECTIVE designations, meaning ALL THE THINGS which have the power to produce in a stream of consciousness excitement of a certain particular sort ( James, 1890 , p. 319, emphasis in original).

James (1890) chose the word “Me” to refer to self-as-object. What does it mean? In James’ (1890) view, it reflects “all the things” which have the power to produce “excitement of a certain particular sort.” This certain kind of excitement is nothing more than some form of experiential quality of me-ness, mine-ness, or similar - understood in a folk-theoretical way (this is an important point, because these terms have recently acquired technical meanings in philosophy, e.g., Zahavi, 2014 ; Guillot, 2017 ). What are “all the things”? The classic formulation suggests that James (1890) meant physical objects and cultural artifacts (material self), human beings (social self), and mental processes and content (spiritual self). These are all valid categories of self-as-object, however, for the purpose of this paper I will limit the scope of further discussion only to “objects” which are relevant when speaking about consciousness. Therefore, rather than speaking about, for example, my car or my body, I will discuss only their conscious representations. This limits the scope of self-as-object to one category of “things” – conscious mental content.

Let us now reformulate James’ (1890) idea in more contemporary terms and define “Me” as the totality of all content of consciousness that is experienced as self-related. Content of consciousness is meant here in a similar way to Chalmers (1996) , who begins “ The conscious mind ” by providing a list of different kinds of conscious content. He delivers an extensive (without claiming that exhaustive) collection of types of experiences, which includes the following 4 : visual; auditory; tactile; olfactory; experiences of hot and cold; pain; taste; other bodily experiences coming from proprioception, vestibular sense, and interoception (e.g., headache, hunger, orgasm); mental imagery; conscious thought; emotions. Chalmers (1996) also includes several other, which, however, reflect states of consciousness and not necessarily content per se , such as dreams, arousal, fatigue, intoxication, and altered states of consciousness induced by psychoactive substances. What is common to all of the types of experience from the first list (conscious contents) is the fact that they are all, speaking in James’ (1890) terms, “objects” in a stream of consciousness: “all these things are objects, properly so called, to the subject that does the thinking” (p. 325).

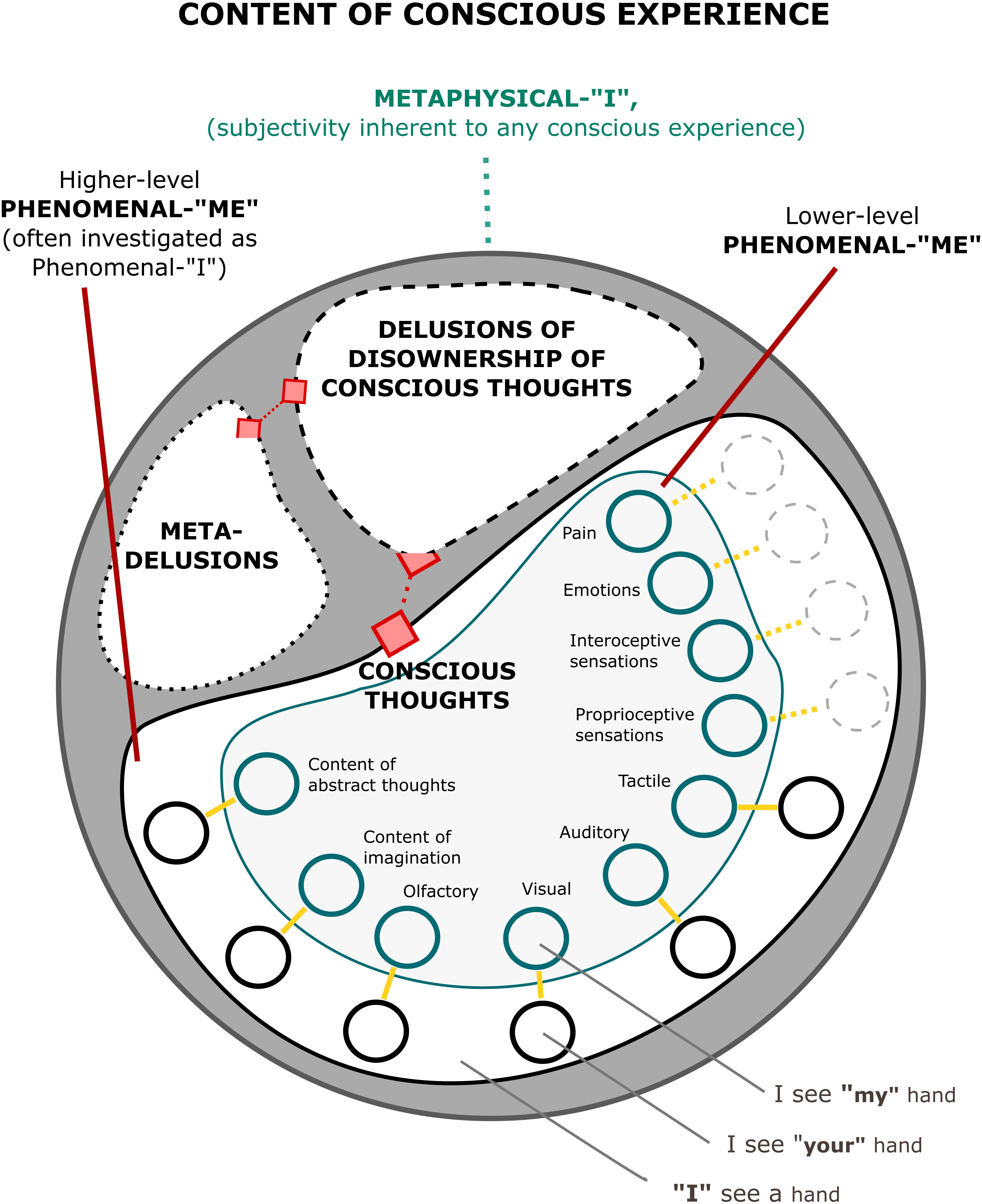

The self understood as “Me” can be understood as a subset of a set of all these possible experiences. This subset is characterized by self-relatedness (Figure 2 ). It can be illustrated with sensory experiences. For example, in the visual domain, I experience an image of my face as different from another person’s face. Hence, while the image of my face belongs to “Me,” the image of someone else does not (although it can be experimentally manipulated, Tsakiris, 2008 ; Payne et al., 2017 ; Woźniak et al., 2018 ). The same can be said about my voice and sounds caused by me (as opposed to voices of other people), and about my smell. We also experience self-touch as different from touching or being touched by a different person ( Weiskrantz et al., 1971 ; Blakemore et al., 1998 ; Schutz-Bosbach et al., 2009 ). There is even evidence that we process our possessions differently ( Kim and Johnson, 2014 ; Constable et al., 2018 ). This was anticipated by James’ (1890) notion of the material “Me,” and is typically regarded as reflecting one’s extended self ( Kim and Johnson, 2014 ). In all of these cases, we can divide sensory experiences into the ones which do relate to the self and the ones which do not. The same can be said about the contents of thoughts and feelings, which can be either about “Me” or about something/someone else.

FIGURE 2. A simplified representation of a structure of phenomenal content including the metaphysical “I,” the phenomenal “Me,” and the phenomenal “I,” which can be understood (see in text) as a higher-level element of the phenomenal “Me.” Each pair of nodes connected with a yellow line represents one type of content of consciousness, with indigo nodes corresponding to self-related content, and black nodes corresponding to non-self-related content. In some cases (e.g., pain, emotions, interoceptive, and proprioceptive sensations), the black nodes are lighter and drawn with a dashed line (the same applies to links), to indicate that in normal circumstances one does not experiences these sensations as representing another person (although it is possible in thought experiments and pathologies). Multisensory/multimodal interactions have been omitted for the sake of clarity. All of the nodes compose the set of conscious thoughts, which can be formulated as “I experience X.” In normal circumstances, one does not deny ownership over these thoughts, however, in thought experiments, and in some cases of psychosis, one may experience that even such thoughts cease to feel as one’s own. This situation is represented by the shape with a dashed outline. Moreover, in special cases one can form meta-delusions, i.e., delusions about delusions – thoughts that my thoughts about other thoughts are not my thoughts (see text for description).

Characterizing self-as-object as a subset of conscious experiences specifies the building blocks of “Me” (which are contents of consciousness) and provides a guiding principle for distinguishing between self and non-self (self-relatedness). However, it is important to note two things. First, the distinction between self and non-self is often a matter of scale rather than a binary classification, and therefore self-relatedness may be better conceptualized as the strength of the relation with the self. It can be illustrated with an example of the “Inclusion of Other in Self” scale ( Aron et al., 1992 ). This scale asks to estimate to what extent another person feels related to one’s self, by choosing among a series of pairs of more-to-less overlapping circles representing the self and another person (e.g., a partner). The degree of overlap between the chosen pair of circles represents the degree of self-relatedness. Treating self-relatedness as a matter of scale adds an additional level of complexity to the analysis, and results in speaking about the extent to which a given content of consciousness represents self, rather than whether it simply does it or not. This does not, however, change the main point of the argument that we can classify all conscious contents according to whether (or to what extent, in that case) they are self-related. For the sake of clarity, I will continue to speak using the language of binary classification, but it should be kept in mind that it is an arbitrary simplification. The second point is that this approach to “Me” allows one to flexibly discuss subcategories of the self by imposing additional constraints on the type of conscious content that is taken into account, as well as the nature of self-relatedness (e.g., whether it is ownership of, agency over, authorship, etc.). For example, by limiting ourselves to discussing conscious content representing one’s body one can speak about the bodily self, and by imposing limits to conscious experience of one’s possessions one can speak about one’s extended self.

Keeping these reservations in mind two objections can be raised to the approach to “Me” introduced here. The first one is as follows:

(1) Speaking about the self/other distinction does not make sense in regard to experiences which are always “mine,” such as prioprioception or interoception. This special status may suggest that these modalities underpin the self as “I,” i.e., the subject of experience.

This idea is present in theoretical proposals postulating that subjectivity emerges based on (representations of) sensorimotor ( Gallagher, 2000 ; Christoff et al., 2011 ; Blanke et al., 2015 ) or interoceptive signals ( Damasio, 1999 ; Craig, 2010 ; Seth et al., 2011 ; Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014 ; Salomon, 2017 ). There are two answers to this objection. First, the fact that this kind of experience (this kind of content of consciousness) is always felt as “my” experience simply means that all proprioceptive, interoceptive, pain experiences, etc., are as a matter of fact parts of “Me.” They are self-related contents of consciousness and hence naturally qualify as self-as-object. Furthermore, there is no principled reason why the fact that we normally do not experience them as belonging to someone else should transform them from objects of experience (content) into a subject of experience. Their special status may cause these experiences to be perceived as more central aspects of the self than experiences in other modalities, but there is no reason to think that it should change them from something that we experience into the self as an experiencer. Second, even the special status of these sensations can be called into question. It is possible to imagine a situation in which one experiences these kinds of sensations from an organ or a body which does not belong to her or him. We can imagine that with enough training one will learn to distinguish between proprioceptive signals coming from one’s body and those coming from another person’s (or artificial) body. If this is possible, then one may develop a phenomenal distinction between “my” versus “other’s” proprioceptive and interoceptive experiences (for example), and in this case the same rules of classification into phenomenal “Me” and phenomenal “not-Me” will apply as to other sensory modalities. This scenario is not realistic at the current point of technological development, but there are clinical examples which indirectly suggest that it may be possible. For example, people who underwent transplantation of an organ sometimes experience rejection of a transplant. Importantly, patients whose organisms reject an organ also more often experience psychological rejection of that transplant ( Látos et al., 2016 ). Moreover, there are rare cases in which patients following a successful surgery report that they perceive transplanted organs as foreign objects in themselves ( Goetzmann et al., 2009 ). In this case, affected people report experiencing a form of disownership of the implanted organ, suggesting that they may experience interoceptive signals coming from that transplant as having a phenomenal quality of being “not-mine,” leading to similar phenomenal quality as the one postulated in the before-mentioned thought experiment. Another example of a situation in which self-relatedness of interoception may be disrupted may be found in conjoint twins. In some variants of this developmental disorder (e.g., parapagus, dicephalus, thoracopagus) brains of two separate twins share some of the internal organs (and limbs), while others are duplicated and possessed by each twin individually ( Spencer, 2000 ; Kaufman, 2004 ). This provides an inverted situation to the one described in our hypothetical scenario – rather than two pieces of the same organ being “wired” to one person, the same organ (e.g., a heart, liver, stomach) is shared by two individuals. As such it may be simultaneously under control of two autonomous nervous systems. This situation raises challenging questions for theories which postulate that the root of self-as-subject lies in interoception. For example, if conjoint twins share the majority of internal organs, but possess mostly independent nervous systems, like dicephalus conjoint twins, then does it mean that they share the neural subjective frame ( Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014 )? If the answer is yes, then does it mean that they share it numerically (both twins have one and the same subjective frame), or only qualitatively (their subjective frames are similar to the point of being identical, but they are distinct frames)? However, if interoception is just a part of “Me” then the answer becomes simple – the experiences can be only qualitatively identical, because they are experienced by two independent subjects.

All of these examples challenge the assumption that sensori-motor and interoceptive experiences are necessarily self-related and, as a consequence, that they can form the basis of self-as-subject. For this reason, it seems that signals coming from these modalities are more appropriate to underlie the phenomenal “Me,” for example in a form of background self-experience, or “phenomenal background” ( Dainton, 2008 , 2016 ), rather than the phenomenal “I.”

The second possible objection to the view of self-as-object described in this section is the following one:

(2) My thoughts and feelings may have different objects, but they are always my thoughts and feelings. Therefore, their object may be either “me” or “other,” but their subject is always “I.” As a consequence, even though my thoughts and feelings constitute contents of my consciousness, they underlie the phenomenal “I” and not the phenomenal “Me.”

It seems to be conceptually misguided to speak about one’s thoughts and feelings as belonging to someone else. This intuition motivated Wittgenstein (1958) to write: “there is no question of recognizing a person when I say I have toothache. To ask ‘are you sure it is you who have pains?’ “would be nonsensical” ( Wittgenstein, 1958 ). In the Blue Book, he introduced the distinction between the use of “I” as object and as subject (see Table 1 for a full relevant quote) and suggested that while we can be wrong about the former, making a mistake about the latter is not possible. This idea was further developed by Shoemaker (1968) who introduced an arguably conceptual truth that we are immune to error through misidentification relative to the first-person pronoun, or IEM in short. For example, when I say “I see a photo of my face in front of me” I may be mistaken about the fact that it is my face (because, e.g., it is a photo of my identical twin), but I cannot be mistaken that it is me who is looking at it. One way to read IEM is that it postulates that I can be mistaken about self-as-object, but I cannot be mistaken about self-as-subject. If this is correct then there is a radical distinction between these two types of self that provides a strong argument to individuate them. From that point, one may argue that IEM provides a decisive argument to distinguish between phenomenal “I” (self-as-subject) and phenomenal “Me” (self-as-object).

Before endorsing this conclusion, let us take a small step back. It is important to note that in the famous passage from the Blue Book Wittgenstein (1958) did not write about two distinct types of self. Instead, he wrote about two ways of using the word “I” (or “my”). As such, he was more concerned with issues in philosophy of language than philosophy of mind. Therefore, a natural question arises – to what extent does this linguistic distinction map onto a substantial distinction between two different entities (types of self)? On the face of it, it seems that there is an important difference between these two uses of self-referential words, which can be mapped onto the experience of being a self-as-subject and the experience of being a self-as-object (or, for example, the distinction between bodily ownership and thought authorship, as suggested by Liang, 2014 ). However, I will argue that there are reasons to believe that the phenomenal “I,” i.e., the experience of being a self-as-subject may be better conceptualized as a higher-order phenomenal “Me” – a higher-level self-as-object.

Psychiatric practice provides cases of people, typically suffering from schizophrenia, who describe experiences of dispossession of thoughts, known as delusions of thought insertion ( Young, 2008 ; Bortolotti and Broome, 2009 ; Martin and Pacherie, 2013 ). According to the standard account, the phenomenon of thought insertion does not represent a disruption of sense of ownership over one’s thoughts, but only loss of sense of agency over them. However, the standard account has been criticized in recent years by theorists arguing that thought insertion indeed represents loss of sense of ownership ( Metzinger, 2003 ; Billon, 2013 ; Guillot, 2017 ; López-Silva, 2017 ). One of the main arguments against the standard view is that it runs into serious problems when attempting to explain obsessive intrusive thoughts in clinical population and spontaneous thoughts in healthy people. In both cases, subjects report lack of agency over thoughts, although they never claim lack of ownership over them, i.e., that these are not their thoughts. However, if the standard account is correct, obsessive thoughts should be experienced as belonging to someone else. The fact that they are not suggests that something else must be disrupted in delusions of thought insertion, i.e., sense of ownership 5 over them. If one can lose sense of ownership over one’s thoughts then it has important implications, because then one becomes capable of experiencing one’s thoughts “as someone else’s,” or at least “as not-mine.” However, when I experience my thoughts as not-mine I do it because I’ve taken a stance towards my thoughts, which treats them as an object of deliberation. In other words, I must have “objectified” them to experience that they have a quality of “feeling as if they are not mine.” Consequently, if I experience them as objects of experience, then they cannot form part of my self as subject of experience, because these two categories are mutually exclusive. Therefore, what seemed to constitute a phenomenal “I” turns out to be a part of thephenomenal “Me.”

If my thoughts do not constitute the “I” then how do they fit into the structure of “Me”? Previously, I asserted that thoughts with self-related content constitute “Me,” while thoughts with non-self related content do not. However, just now I argued in favor of the claim that all thoughts (including the ones with non-self-related content) that are experienced as “mine” belong to “Me.” How can one resolve this contradiction?

A way to address this reservation can be found in Metzinger’s (2003 ; 2010 ) self-model theory. Metzinger (2003 , 2010 ) argues that the experience of the self can be understood as underpinned by representational self-models. These self-models, however, are embedded in the hierarchical representational structure, as illustrated by an account of ego dissolution by Letheby and Gerrans (2017) :

Savage suggests that on LSD “[changes] in body ego feeling usually precede changes in mental ego feeling and sometimes are the only changes” (1955, 11), (…) This common temporal sequence, from blurring of body boundaries and loss of sense of ownership for body parts through to later loss of sense of ownership for thoughts, speaks further to the hierarchical architecture of the self-model. ( Letheby and Gerrans, 2017 , p. 8)

If self-models underlying the experience of self-as-object (“Me”) are hierarchical, then the apparent contradiction may be easily explained by the fact that when speaking about the content of thoughts and the thoughts themselves we are addressing self-models at two distinct levels. At the lower level we can distinguish between thoughts with self-related content and other-related content, while on the higher level we can distinguish between thoughts that feel “mine” as opposed to thoughts that are not experienced as “mine.” As a result, this thinking phenomenal “I” experienced in feeling of ownership over one’s thoughts may be conceived as just a higher-order level of Jamesian “Me.” As such, one may claim that there is no such thing as a phenomenal “I,” just multilevel phenomenal “Me.” However, an objection can be raised here. One may claim that even though a person with schizophrenic delusions experiences her thoughts as someone else’s (a demon’s or some malicious puppet master’s), she can still claim that:

Yes, “I” experience my thoughts as not mine, but as demon’s.” My thoughts feel as “not-mine,” however, it’s still me (or: “I”) who thinks of them as “not-mine.”

As such, one escapes “objectification” of “I” into “Me” by postulating a higher-level phenomenal-“I.” However, let us keep in mind that the thought written above constitutes a valid thought by itself. As such, this thought is vulnerable to the theoretical possibility that it turns into a delusion itself, once a psychotic person forms a meta-delusion (delusion about delusion). In this case, one may begin to experience that: “I” (I 1 ) experience that the “fake I” (I 2 ), who is a nasty pink demon, experiences my thoughts as not mine but as someone else’s (e.g., as nasty green demon’s). In this case, I may claim that the real phenomenal “I” is I 1 , since it is at the top of the hierarchy. However, one may repeat the operation of forming meta-delusions ad infinitum (as may happen in psychosis or drug-induced psychedelic states) effectively transforming each phenomenal “I” into another “fake-I” (and consequently making it a part of “Me”).

The possibility of meta-delusions illustrates that the phenomenal “I” understood as subjective thoughts is permanently vulnerable to the threat of losing the apparent subjective character and becoming an object of experience. As such it seems to be a poor choice for the locus of subjectivity, since it needs to be constantly “on the run” from becoming treated as an object of experience, not only in people with psychosis, but also in all psychologically healthy individuals if they decide to reflect on their thoughts. Therefore, it seems more likely that the thoughts themselves cannot constitute the subject of experience. However, even in case of meta-delusions there seems to be a stable deeper-level subjectivity, let us call it the deep “I,” which is preserved, at least until one loses consciousness. After all, a person who experiences meta-delusions would be constantly (painfully) aware of the process, and often would even report it afterwards. This deep “I” cannot be a special form of content in the stream of consciousness, because otherwise it would be vulnerable to becoming a part of “Me.” Therefore, it must be something different.

There seem to be two places where one can look for this deep “I”: in the domain of phenomenology or metaphysics. The first approach has been taken by ( Zahavi and Kriegel, 2016 ) who argue that “all conscious states’ phenomenal character involves for-me-ness as an experiential constituent.” It means that even if we rule out everything else (e.g., bodily experiences, conscious thoughts), we are still left with some form of irreducible phenomenal self-experience. This for-me-ness is not a specific content of consciousness, but rather “refers to the distinct manner, or how , of experiencing” ( Zahavi, 2014 ).

This approach, however, may seem inflationary and not satisfying (e.g., Dainton, 2016 ). One reason for this is that it introduces an additional phenomenal dimension, which may lead to uncomfortable consequences. For example, a question arises whether for-me-ness can ever be lost or replaced with the “ how of experiencing” of another person. For example, can I experience my sister’s for-me-ness in my stream of consciousness? If yes, then how is for-me-ness different from any other content of consciousness? And if the answer is no, then how is it possible to distil the phenomenology of for-me-ness from the metaphysical fact that a given stream of consciousness is always experienced by this and not other subject?

An alternative approach to the problem of the deep “I” is to reject that the subject of experience, the “I,” is present in phenomenology (like Hume, 1739/2000 ; Prinz, 2012 ; Dainton, 2016 ), and look for it somewhere else, in the domain of metaphysics. Although James (1890) did not explicitly formulate the distinction between “Me” and “I” as the distinction between the phenomenal and the metaphysical self, he hinted at it at several points, for example when he concluded the Chapter on the self with the following fragment: “(...) a postulate, an assertion that there must be a knower correlative to all this known ; and the problem who that knower is would have become a metaphysical problem” ( James, 1890 , p. 401).

“I” As A Subject Of Experience: Metaphysics Of Subjectivity

Thoughts which we actually know to exist do not fly about loose, but seem each to belong to some one thinker and not to another ( James, 1890 , pp. 330–331).

Let us assume that phenomenal consciousness exists in nature, and that it is a part of the reality we live in. The problem of “I” emerges once we realize that one of the fundamental characteristics of phenomenal consciousness is that it is always subjective, that there always seems to be some subject of experience. It seems mistaken to conceive of consciousness which do “fly about loose,” devoid of subjective character, devoid of being someone’s or something’s consciousness. Moreover, it seems that subjectivity may be one of the fundamental inherent properties of conscious experience (similar notions can be found in: Berkeley, 1713/2012 ; Strawson, 2003 ; Searle, 2005 ; Dainton, 2016 ). It seems highly unlikely, if not self-contradictory, that there exists something like an objective conscious experience of “what it is like to be a bat” ( Nagel, 1974 ), which is not subjective in any way. This leads to the metaphysical problem of the self: why is all conscious experience subjective, and what or who is the subject of this experience? Let us call it the problem of the metaphysical “I,” as contrasted with the problem of the phenomenal “I” (i.e., is there a distinctive experience of being a self as a subject of experience, and if so, then what is this experience?), which we discussed so far.

The existence of the metaphysical “I” does not entail the existence of the phenomenal self. It is possible to imagine a creature that possesses a metaphysical “I,” but does not possess any sense of self. In such a case, the creature would possess consciousness, although it would not experience anything as “me,” nor entertain any thoughts/feelings, etc., as “I.” In other words, it is a possibility that one may not experience self-related content of consciousness, while being a sentient being. One example of such situation may be the experience of a dreamless sleep, which “is characterized by a dissolution of subject-object duality, or (…) by a breakdown of even the most basic form of the self-other distinction” ( Windt, 2015 ). This is a situation which can be regarded as an instance of the state of minimal phenomenal experience – the simplest form of conscious experience possible ( Windt, 2015 ; Metzinger, 2018 ), in which there is no place for even the most rudimentary form of “Me.” Another example may be the phenomenology of systems with grid-like architectures which, according to the integrated information theory (IIT, Tononi et al., 2016 ), possess conscious experience 6 . If IIT is correct, then these systems experience some form of conscious states, which most likely lack any phenomenal distinction between “Me” and “not-Me.” However, because they may possess a stream of conscious experience, and conscious experience is necessarily subjective, there remains a valid question: who or what is the subject of that experience?

The question of what exactly is the metaphysical subject of experience can have different answers. There has been a long history of theories of the self ( Barresi and Martin, 2011 ) and some of them directly address this issue. Platonic or Cartesian notions of the soul are good examples of an approach providing one answer to this question: conscious experience is subjective, because there exists a non-material being (self, soul) which is the subject of this experience (see Table 3 ). Other solutions tend to either define the self in less metaphysically expensive ways ( Johnston, 1987 ; Strawson, 2000 ; Dainton, 2008 ), define it as a formal feature of consciousness ( Searle, 2005 ), or deny the need to postulate its existence ( Metzinger, 2003 ). What is crucial here, however, is that the problem of the metaphysical self is a different issue and requires a different methodology, than the problem of the phenomenal self.

TABLE 3. Examples of theories of the self-as-subject (“I”) in the context of consciousness, as theories of the metaphysical self, with representative quotes illustrating each position.

What sort of methodology, then, is appropriate for investigating the metaphysical self? It seems that the most relevant methods come from the toolbox of metaphysics. This toolbox includes classical philosophical methods such as thought experiments and logical analysis. However, methodology of metaphysics is an area of open discussion, and at present there are no signs of general consensus. One of the most debated issues in this field, which is especially relevant here, is to what extent the methodology of metaphysics is continuous with the methodology of natural sciences (see Tahko, 2015 , Chapter 9 for an overview). The positions span the spectrum between the claim that science and metaphysics are fully autonomous on the one side and the claim that metaphysics can be fully naturalized on the other. Discussing this issue goes way beyond the scope of this paper. However, if these two areas are at least to some extent related (i.e., not fully autonomous), then one may argue that scientific methods can be at least of some relevance in metaphysics and consequently for investigations of the metaphysical “I.”

One example in which empirical results seem to be able to influence theoretical investigations of the metaphysical self is through imposing constraints on philosophical theories. For example, because the metaphysical self is inherently related to consciousness, we should expect that different theories of consciousness should place different constraints on what a metaphysical self can be. Then, if one theory of consciousness acquires stronger empirical support than the others, we can also treat this as evidence for the constraints on the self that this theory implies.

Let us look at an example of IIT to illustrate this point. According to IIT ( Oizumi et al., 2014 ; Tononi et al., 2016 ) the content of conscious experience is defined by the so-called informational “complex” which is characterized by maximally integrated information (which can be measured by calculating the value of Φ max ). This complex then defines the stream of conscious experience. However, what happens if there is more than one such complex in one person? In this case, as Tononi et al. (2016) wrote:

According to IIT, two or more non-overlapping complexes may coexist as discrete physical substrates of consciousness (PSCs) within a single brain, each with its own definite borders and value of Φ max . The complex that specifies a person’s day to day stream of consciousness should have the highest value of Φ max – that is, it should be the “major” complex. In some conditions, for example, after a split-brain operation, the major complex may split. In such instances, one consciousness, supported by a complex in the dominant hemisphere and with privileged access to Broca’s area, would be able to speak about the experience, but would remain unaware of the presence of another consciousness, supported by a complex in the other hemisphere, which can be revealed by carefully designed experiments. ( Tononi et al., 2016 , p. 455)

This fragment suggests that in IIT the metaphysical “I” can be understood as tied to a complex of maximally integrated information. In this case, a split-brain patient would possess two metaphysical selves, because as a consequence of an operation her or his brain hosts two such complexes. On the face of it, it seems to be a plausible situation ( cf. Bayne, 2010 ). However, in the sentence which immediately follows, Tononi et al. (2016) suggest that: