A Rhetorical Analysis of Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”

Frank Coffman - WORDSMITH

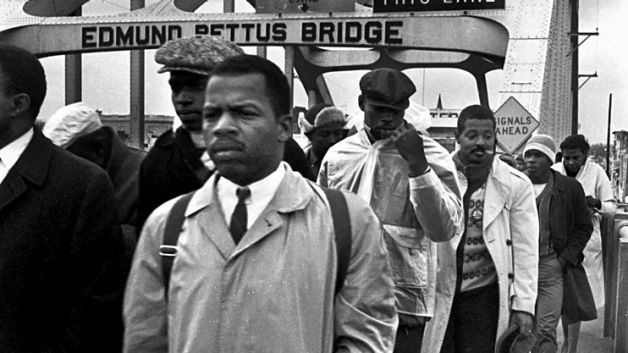

NOTE: The image of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg is greatly enlarged from a glass plate original in which the face is a mere speck in a crowd of likely 1000 people and taken from a distance of likely 100 yards. The only other possible photos of Lincoln at Gettysburg are of a man on horseback in a tall top hat thought to be, quite likely, Lincoln. This is the only extant image of him on the speaking platform.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Lincoln’s rhetorical mastery is exhibited from the beginning of this speech. In just 278 words, he displays most of the typical figures of his style. One important thing about gaining a knowledge of some of the most common figures (that I am highlighting in this series — nowhere near the number of recognized figures*) is one’s ability — through their understanding — of doing RHETORICAL ANALYSIS . One can go beyond mere generalities such as “eloquent,” “powerful,” “evocative,” “grand,” “noble,” etc. and say specific things about rhetorical tendencies in the style of any speaker or writer.

In the first sentence (which, by the way, is a one-sentence paragraph — yes, I know that you had a teacher [or several] who told you “Never write a one-sentence paragraph!” BUT this is one of many “training-wheels rules,” as I call them — meant to “drop away” as one’s style and understanding of language becomes more sophisticated), Lincoln comes directly at the audience with several interesting figures.

First, to turn to the PHONIC SCHEMES and the “sound effects” of Lincoln’s language , “Four score” is a RHYME . Now, while it’s true that the prose writer does not often find uses for rhyme, its extreme rarity does not mean that it never works with prose. “Does might make right?” is another good example. Also, in this first sentence-paragraph, his love of ALLITERATION is shown: the Ss, Fs, Ns, and hard Cs echo. ASSONANCE (the noticeable repetition of vowel sounds) is also heavy with the long open O sounds of “score,” “ago,” “our,” “brought,” “forth,” “upon,” “continent,” “conceived,” “to,” “proposition.” Impressive stuff. We also have heavy CONSONANCE (the noticeable repetition of medial and terminal consonant sounds) is quite evident with the heavy use of the rolling R sounds: “FouR, scoRe, YeaRs, OuR, FatheRs, BRought, FoRth.”

Second, Lincoln’s use of the ARCHAISM of Biblical language and saying “Four score and seven” rather than “eighty-seven” (which he would normally have said in regular conversation) adds nobility and authority to the opening. Of course, 1863 — the year of delivery of the speech — is eighty-seven years after 1776 and the Declaration of Independence .

Third, we also have the use of two very SPECIAL MODES OF ALLITERATION: He begins with alliterations on the letter sounds of “P” and “F” (“Four, fathers, forth, proposition”) — which will be used as “threads of sound” to bind this speech together. He also begins a special arrangement of what I will call “ENVELOPE ALLITERATION” by putting two letter sounds on either side of an alliterative “double” with “continent, new, nation, conceived.” We will see this pattern repeated multiple times in this short speech — enough to prove that Lincoln’s use of it is intentional.

Turning to the second paragraph, it is important to note that the entire speech is only three paragraphs long — AND that it moves with an organizational pattern of Past-Present-Future: “Four score and seven years ago…,” “Now…,” then to what we can and should and must do from here on out. I will look at the following paragraphs in sections.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

The use of PARALLELISM here can be seen in the repetition of the words “nation,” “conceived,” and “dedicated” in the same order as in paragraph one.

We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.

Parallel structuring continues here with different varieties of its use. First, the most common “signal” of parallel structuring is the use of ANAPHORA (the repeated opening, literally from the Greek: “first phrase). Continuing from “we are engaged” in the previous sentence, Lincoln’s next two sentences begin: “We are met…” and “We have come… .” We may disregard the initial “Now” at the beginning of paragraph two as a word needed merely for transition from Past to Present and see the “We” clauses in perfect parallel introductory. Here we also see what is perhaps Lincoln’s favorite figure: TRICOLON (Greek: “three parts,” “three clauses” in parallel). He will use it three times in this short speech. And, as far as “series” go, three is likely the smallest number to safely call a “series.” It was old stuff when Julius Caesar was a schoolboy, and his famous “Veni, Vidi, Vici” is a beautiful example (also using nifty alliteration in the Latin — and, by the way, another rhetorical device, ISOCOLON (Greek: “equal parts,” “equal clauses” — the perfect repetition of grammatical structure in parallelism). We also have the parallel effect of DIMINUTIO (Latin this time: “growing smaller”) in that we go from “great civil war,” to “great battlefield,” to “portion of that field.” In effect, this is a “zooming in” (to compare to photography) — going from greatest to least, largest image to smallest.

Going back to PHONIC SCHEMES and SPECIAL PATTERNS , notice the Fs and Ps continuing. Lincoln binds this entire speech together with alliteration on these sounds: “field,” “portion,” “field,” “final,” “place.” We also see the envelope alliteration working again: “portion-field-final-place” AND in “those-who-here-their” (note that, even thought “who” begins with a W, we pronounced it with an opening “H” as with “here”), and, amazingly, also “lives-that-that-live.” It is becoming more and more clear that Lincoln is intentionally using this “wrap-around pattern of alliteration.

AND, with the repetition in one sentence of LIVES and LIVE, we have POLYPTOTON (the use of two or more words from the same root idea in the same sentence — in different parts of speech — here we have noun and verb, but words such as “Life,” Living,” “Lively,” “Lifeless,” etc. would also have achieved this)

It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

Note the continuation of F and P with “fitting” and “proper.”

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground.

WOW! Now if Honest Abe can use a conjunction to start a sentence — so can you. Here is another “training-wheels rule” propounded by untold legions of grade school and English teachers and professors. There is nothing wrong with conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence on occasions: To show contrast BUT…, or to add something important AND…, or to insert some questioning, YET…, or to bring something to a close SO…, etc. I call this ( from the Greek: PROSYNDETON (“conjunction at the beginning” — our word “synthesis” comes from the same root: syndeton — in Latin it’s con-junctio “to join with”). Noting that, the sentence is also a TRICOLON and, what is more, includes the use of ASYNDETON (Greek: “no conjunctions”), since there is no “and” before the final, “we cannot hallow this ground.” Yes, another “training-wheels rule” and you may forget your teacher’s advice to “Always use a conjunction before the last item in a series.” X, Y, Z works as well as X, Y, and Z . We understand the series without the need for the final “and.” Here we also have KLIMAX in the series. This is the opposite of DIMINUTIO and the items go from least to greatest: dedication is a human thing (“We’d like to dedicate this song to…”; “consecrate” means to make sacred; “hallow” means to make or revere as holy.

The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

Again, the ideas of Life and Death are a big part of this speech. We’ve already seen “gave their lives that that nation might live .” Later we will find another POLYSYNDETON in “that these dead shall not have died in vain.” Also note the continuation of alliteration on Fs and Ps: “far-poor-power.” We also have another “envelope”: “above-poor-power-add”

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

This is a masterpiece of sound effects and the final proof (if any were needed) that Lincoln is intentionally doing this “wrap-around alliteration.” Notice the string of words: “world will little note nor long remember what we.” The first letter sounds to: WWLNNL(r)WW! We see double-Ws wrapped around Ls wrapped around Ns! We also find the parallelism SCHEME of ANTITHESIS (Greek: “against the statement” — a balance of opposites). In effect, Lincoln is saying (although, paradoxically, the opposite has proven to be the case) that: “The world will soon forget what we say here; it can never forget what they did here.” We go from soon forgetting to never forgetting, from saying to doing. A balance of opposites.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us

Here we gave the use of the parallel device of PARAPHRASIS (paraphrase) in that Lincoln is urging attention to “the unfinished work” that he repeats as “the great task before us.” But note that this is NOT an exact paraphrase . The addition of the word “great” in the repeat makes the direct parallel of “unfinished work” and “task remaining” importantly different in the paraphrase. This is called INCREMENTAL PARAPHRASE in which some “tidbit” of extra meaning is included in the repeat. AND, not only do we have many more F alliterations: “for, fought, far, for [as well as the “hidden” Fs in “unfinished” and “before”], But we also have more “envelope alliteration”: “they-here-have-thus” and “fought-here-have-far” (those two sort of overlapping). We also see a subtle use of the memorable figure of CHIASMUS (Greek: X (chi)-shape or crossing pattern or repeat in inverse order xy/yx). Lincoln does this in a very complex way. Notice these two CHIASMUS PAIRS: for us…rather / rather for us AND dedicated here / here dedicated. Thus, he gives the impression that, although the parallelism is here, the repetitiousness is mellowed by the paraphrase and chiasmus inversions. This is also an example of the other principle two-part parallelism of BALANCE : two parts on the same theme or making the same essential statement. This is the opposite of antithesis.

— THAT from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion

— THAT we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain

— THAT this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom

— and THAT government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

The great, eloquent finish to this — almost certainly the most famous American presidential speech — is an amazing melding of several Rhetorical Figures.

The last sentence of the speech is 86 words. With ANAPHORA , signaled by the use of the opening word “THAT.” Also, that for four successive parallel clauses makes this an example of a TETRACOLON ( Greek: four parts/clauses in parallel series). Within this structures, each “branch” of the tetracolon has a figure or figures within itself!

1. In the first “branch” we have ANTITHESIS in “we take” vs. “they gave.” (as well as “for-they-the-full” subtly interwoven).

2. In the second branch we have both “envelope alliteration” in “that-here-highly-that.” We also have POLYPTOTON in “dead-died.”

3. In the third branch we have the only TROPE (non-literal figure) in this speech in “birth of freedom.” Nations are not, literally, BORN. We may also now look back to the beginning of the speech and at “a nation CONCEIVED in liberty” to complete the METAPHOR of a nation being conceived and born.

4. And, finally, we have the famous ending that is a TRICOLON within this TETRACOLON : “of the people, by the people, for the people” — which, of course is another example of both ISOCOLON and ASYNDETON. In addition, we have the culmination of all the P and F alliterations: “for-people-people-perish-from.” And, finally we have the opposite of ANAPHORA in that these three parallel phrases all END the same way: “the people.” This is EPIPHORA (the repetition of endings).

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: So, in trying to rhetorically analyze Lincoln’s style — using our new vocabulary of rhetorical figures — we may say that:

- he loves alliteration, even using it in distinctive patterns;

- he loves the figure of the tricolon, exemplified by his use of three of them in this short speech;

- his tendency seems to be very literal, direct language without heavy use of tropes;

- his knowledge and use of parallel figures and of sound effects to make his prose more poetical is distinctive and masterful.

*NOTE: I mention above and elsewhere that these figures I’m covering are a small number of the total identified and named by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The most exhaustive study of figures is done by the German, Heinrich Lausberg, in A DICTIONARY OF LITERARY RHETORIC . Lausberg identifies over 900 figures! For those interested in delving more deeply into the types and uses of Rhetorical Figures, I highly recommend Richard Lanham’s (emeritus professor of Rhetoric, UCLA) and his A HANDLIST OF RHETORICAL TERMS.

Written by Frank Coffman - WORDSMITH

Frank Coffman is a published poet, author, scholarly researcher, and retired professor of English, Creative Writing, and Journalism. frankcoffman-writer.net

Text to speech

A Summary and Analysis of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Here’s a question for you. Who was the main speaker at the event which became known as the Gettysburg Address? If you answered ‘Abraham Lincoln’, this post is for you. For the facts of what took place on the afternoon of November 19, 1863, four and a half months after the Union armies defeated Confederate forces in the Battle of Gettysburg, have become shrouded in myth. And one of the most famous speeches in all of American history was not exactly a resounding success when it was first spoken.

What was the Gettysburg Address?

The Gettysburg Address is the name given to a short speech (of just 268 words) that the US President Abraham Lincoln delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (which is now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery) in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on 19 November 1863. At the time, the American Civil War was still raging, and the Battle of Gettysburg had been the bloodiest battle in the war, with an estimated 23,000 casualties.

Gettysburg Address: summary

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

The opening words to the Gettysburg Address are now well-known. President Abraham Lincoln begins by harking back ‘four score and seven years’ – that is, eighty-seven years – to the year 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was signed and the nation known as the United States was founded.

The Declaration of Independence opens with the words: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal’. Lincoln refers to these words in the opening sentence of his declaration.

However, when he uses the words, he is including all Americans – male and female (he uses ‘men’ here, but ‘man’, as the old quip has it, embraces ‘woman’) – including African slaves, whose liberty is at issue in the war. The Union side wanted to abolish slavery and free the slaves, whereas the Confederates, largely in the south of the US, wanted to retain slavery.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

Lincoln immediately moves to throw emphasis on the sacrifice made by all of the fallen soldiers who gave their lives at Gettysburg, and at other battles during the Civil War. He reminds his listeners that the United States is still a relatively young country, not even a century old yet.

Will it endure when it is already at war with itself? Can all Americans be convinced that every single one of them, including its current slaves, deserves what the Declaration of Independence calls ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’?

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate – we can not consecrate – we can not hallow – this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

Lincoln begins the third and final paragraph of the Gettysburg Address with a slight rhetorical flourish: the so-called rule of three, which entails listing three things in succession. Here, he uses three verbs which are roughly synonymous with each other – ‘dedicate’, ‘consecrate’, ‘hallow’ – in order to drive home the sacrifice the dead soldiers have made. It is not for Lincoln and the survivors to declare this ground hallowed: the soldiers who bled for their cause have done that through the highest sacrifice it is possible to make.

Note that this is the fourth time Lincoln has used the verb ‘dedicate’ in this short speech: ‘and dedicated to the proposition …’; ‘any nation so conceived and so dedicated …’; ‘We have come to dedicate a portion …’; ‘we can not dedicate …’. He will go on to repeat the word twice more before the end of his address.

Repetition is another key rhetorical device used in persuasive writing, and Lincoln’s speech uses a great deal of repetition like this.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln concludes his address by urging his listeners to keep up the fight, so that the men who have died in battles such as the Battle of Gettysburg will not have given their lives in vain to a lost cause. He ends with a now-famous phrase (‘government of the people, by the people, for the people’) which evokes the principle of democracy , whereby nations are governed by elected officials and everyone has a say in who runs the country.

Gettysburg Address: analysis

The mythical aura surrounding the Gettysburg Address, like many iconic moments in American history, tends to obscure some of the more surprising facts from us. For example, on the day Lincoln delivered his famous address, he was not the top billing: the main speaker at Gettysburg on 19 November 1863 was not Abraham Lincoln but Edward Everett .

Everett gave a long – many would say overlong – speech, which lasted two hours . Everett’s speech was packed full of literary and historical allusions which were, one feels, there to remind his listeners how learned Everett was. When he’d finished, his exhausted audience of some 15,000 people waited for their President to address them.

Lincoln’s speech is just 268 words long, because he was intended just to wrap things up with a few concluding remarks. His speech lasted perhaps two minutes, contrasted with Everett’s two hours.

Afterwards, Lincoln remarked that he had ‘failed’ in his duty to deliver a memorable speech, and some contemporary newspaper reports echoed this judgment, with the Chicago Times summarising it as a few ‘silly, flat and dishwatery utterances’ before hinting that Lincoln’s speech was an embarrassment, especially coming from so high an office as the President of the United States.

But in time, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address would come to be regarded as one of the great historic American speeches. This is partly because Lincoln eschewed the high-flown allusions and wordy style of most political orators of the nineteenth century.

Instead, he wanted to address people directly and simply, in plain language that would be immediately accessible and comprehensible to everyone. There is something democratic , in the broadest sense, about Lincoln’s choice of plain-spoken words and to-the-point sentences. He wanted everyone, regardless of their education or intellect, to be able to understand his words.

In writing and delivering a speech using such matter-of-fact language, Lincoln was being authentic and true to his roots. He may have been attempting to remind his listeners that he belonged to the frontier rather than to the East, the world of Washington and New York and Massachusetts.

There are several written versions of the Gettysburg Address in existence. However, the one which is viewed as the most authentic, and the most frequently reproduced, is the one known as the Bliss Copy . It is this version which is found on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. It is named after Colonel Alexander Bliss, the stepson of historian George Bancroft.

Bancroft asked Lincoln for a copy to use as a fundraiser for soldiers, but because Lincoln wrote on both sides of the paper, the speech was illegible and could not be reprinted, so Lincoln made another copy at Bliss’s request. This is the last known copy of the speech which Lincoln himself wrote out, and the only one signed and dated by him, so this is why it is widely regarded as the most authentic.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Speech Writing

- Delivery Techniques

- PowerPoint & Visuals

- Speaker Habits

- Speaker Resources

- Speech Critiques

- Book Reviews

- Browse Articles

- ALL Articles

- Learn About Us

- About Six Minutes

- Meet Our Authors

- Write for Us

- Advertise With Us

Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of the most famous, most quoted, and most recited speeches of all time . It is also one of the shortest among its peers at just 10 sentences.

In this article, we examine five key lessons which you can learn from Lincoln’s speech and apply to your own speeches.

This is the latest in a series of speech critiques here on Six Minutes .

Speech Critique – Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln

I encourage you to:

- Watch the video with a recitation by Jeff Daniels;

- Read the analysis in this speech critique, as well as the speech transcript below; and

- Share your thoughts on this speech in the comment section .

Lesson #1 – Anchor Your Arguments Solidly

When trying to persuade your audience, one of the strongest techniques you can use is to anchor your arguments to statements which your audience believes in. Lincoln does this twice in his first sentence:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal . [1]

Among the beliefs which his audience held, perhaps none were stronger than those put forth in the Bible and Declaration of Independence. Lincoln knew this, of course, and included references to both of these documents.

First, Psalm 90 verse 10 states:

The days of our years are threescore years and ten …

(Note: a “score” equals 20 years. So, the verse is stating that a human life is about 70 years.)

Therefore, Lincoln’s “Four score and seven years ago” was a Biblically evocative way of tracing backwards eighty-seven years to the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. That document contains the following famous line:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal , that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

By referencing both the Bible and the Declaration of Independence, Lincoln is signalling that if his audience trusts the words in those documents (they did!), then they should trust his words as well.

How can you use this lesson? When trying to persuade your audience, seek out principles on which you agree and beliefs which you share. Anchor your arguments from that solid foundation.

Lesson #2 – Employ Classic Rhetorical Devices

Lincoln employed simple techniques which transformed his words from bland to poetic. Two which we’ll look at here are triads and contrast.

First, he uttered two of the most famous triads ever spoken:

- “…we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground.” [6]

- “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” [10]

- “… for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live .” [4] (the death of the soldiers contrasts with the life of the nation)

- “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here , but it can never forget what they did here .” [8] ( remember contrasts forget ; say contrasts did )

How can you use this lesson? While the stately prose of Lincoln’s day may not be appropriate for your next speech, there is still much to be gained from weaving rhetorical devices into your speech. A few well-crafted phrases often serve as memorable sound bites, giving your words an extended life.

Lesson #3 – Repeat Your Most Important Words

“ When trying to persuade your audience, seek out principles on which you agree and beliefs which you share. Anchor your arguments from that solid foundation. ”

In the first lesson, we’ve seen how words can be used to anchor arguments by referencing widely held beliefs.

In the second lesson, we’ve seen how words can be strung together to craft rhetorical devices.

Now, we’ll turn our attention to the importance of repeating individual words. A word-by-word analysis of the Gettysburg Address reveals the following words are repeated:

- we: 10 times

- here: 8 times

- dedicate (or dedicated): 6 times

- nation: 5 times

While this may not seem like much, remember that his entire speech was only 271 words.

By repetitive use of these words, he drills his central point home: Like the men who died here , we must dedicate ourselves to save our nation .

- “we” creates a bond with the audience (it’s not about you or I, it’s about us together)

- “here” casts Gettysburg as the springboard to propel them forward

- “dedicate” is more powerful than saying “we must try to do this”

- “nation” gives the higher purpose

How can you use this lesson? Determine the words which most clearly capture your central argument. Repeat them throughout your speech, particularly in your conclusion and in conjunction with other rhetorical devices. Use these words in your marketing materials, speech title, speech introduction, and slides as well. Doing so will make it more likely that your audience will [a] “get” your message and [b] remember it.

Lesson #4 – Use a Simple Outline

The Gettysburg Address employs a simple and straightforward three part speech outline : past, present, future.

- Past : The speech begins 87 years in the past, with the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the formation of a new nation. [1]

- Present : The speech then describes the present context: the civil war, a great battlefield (Gettysburg), and a dedication ceremony. The new nation is being tested. [2-8]

- Future : Lincoln paints a picture of the future where the promise of the new nation is fully realized through a desirable relationship between government and the people. [9-10]

How can you use this lesson? When organizing your content, one of the best approaches is one of the simplest. Go chronological.

- Start in the past, generally at a moment of relative prosperity or happiness.

- Explain how your audience came to the present moment. Describe the challenge, the conflict, or the negative trend.

- Finally, describe a more prosperous future, one that can be realized if your audience is persuaded to action by you.

Lesson #5 – State a Clear Call-to-Action

The final sentences of the Gettysburg Address are a rallying cry for Lincoln’s audience. Although the occasion of the gathering is to dedicate a war memorial (a purpose to which Lincoln devotes many words in the body of his speech), that is not Lincoln’s full purpose. He calls his audience to “be dedicated here to the unfinished work” [8], to not let those who died to “have died in vain” [10]. He implores them to remain committed to the ideals set forth by the nation’s founding fathers.

How can you use this lesson? The hallmark of a persuasive speech is a clear call-to-action. Don’t hint at what you want your audience to do. Don’t imply. Don’t suggest. Clearly state the actions that, if taken, will lead your audience to success and prosperity.

Speech Transcript – Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln

[1] Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

[2] Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

[3] We are met on a great battle-field of that war.

[4] We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.

[5] It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

[6] But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground.

[7] The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

[8] The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

[9] It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

[10] It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Other Critiques of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

For further reading, you may enjoy these excellent analyses:

- Nick Morgan — The greatest 250-word speech ever written

- John Zimmer — The Gettysburg Address: An Analysis

- Christopher Graham — A poetical analysis of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

Please share this...

This article is one of a series of speech critiques of inspiring speakers featured on Six Minutes . Subscribe to Six Minutes for free to receive future speech critiques.

Add a Comment Cancel reply

E-Mail (hidden)

Subscribe - It's Free!

| Follow Us |

Similar Articles You May Like...

- Speech Analysis: I Have a Dream – Martin Luther King Jr.

- 5 Speechwriting Lessons from Obama’s Inaugural Speech

- Speech Analysis: Franklin Roosevelt Pearl Harbor Address

- Speech Analysis: Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain”

- Video Critique: J.A. Gamache (Toastmasters, 2007)

- Critique: Lessig Method Presentation Style (Dick Hardt, Identity 2.0, OSCON 2005)

Find More Articles Tagged:

19 comments.

Hi Andrew, Wonderful insights and tools about how speakers can have an effective profound impact on their listeners. I always like reading your entries.

Thank you for this. I will use this and the other speech critiques with my clients. I just finished reading The Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs just a week before his death… we can learn so much from these great presenters.

What an excellent and timely analysis of Lincoln’s address. I especially appreciated your thoughts on Lincoln’s rhetorical devices. In our age of technology and it’s pragmatic focus on precision, efficiency and productivity, the poetic and reflective communicators stand out. I have really enjoyed your blog and resources. Thanks, Andrew. I’ll be back!

I think that Lincoln was a compelling speaker who was able to contrast the negative with positive. His ability to be passionate, to me, shows his genuine sincerity about what he speaks. He really believed in equality for all and it was expressed in his words and their tone. What I took away as important for the speaker is to know your audience and what will move them to action. I think Lincoln was an inspiring speaker that spoke from his heart.This is a truly wonderful way to address others whether or not you are using public speaking as a forum.

Am teaching this right now and your article on the Gettysburg Address dovetails with what I am trying to teach really well. Am going to a link to my blog. Thanks. Dave

Abraham Lincoln’s speeches are always compelling, but this is address is by far my favorite. His way to deliver and emphasize on hi significant points is powerful.

I would like to use this 2011 analysis “Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln” in an upcoming academic presentation. Anyone know a way to get the author’s permission?

Wow, I am impressed and learned so much about using past and present then future references. Ab Lincoln was a lyrical genius

Thank you so much for your website–you have so many wonderful resources! You have helped me with several ideas for a new speech and debate class that I am teaching to 8th graders next year!

Andrew, I saw your FB link to this post and am so happy to have followed the link. As always, your points are right on the money, and provide lots of useful suggestions that all of us can incorporate. It’s amazing what Lincoln conveyed in a mere 271 (or should I say “13 score and 11?”) words, and I like how you broke it into 10 sentences to make it easier to examine.

It’s very interesting to break down speech over 100 years old and see why Abraham Lincoln was one of the best speakers, persuaders, and leaders of our country.

He certainly was.

Andrew, Your analysis of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and tips for speech writing is superb. One thought. I seem to recall discussion of the word “that” in various critical treatments of the GA. I believe Gary Wills gives emphasis to the repetition of “that,” which amounts to 12 times. I recite the GA from memory about twice a month, probably for the last 25 years. I do the same with a number of poems also. I recently ran for Congress in Maryland’s 8th Congressional District. So I have referred to my website above. I used to be a college professor. I’d be interested to share other thoughts about Lincoln and the GA. I discussed Bruce Miroff and his Lincoln in my recent book, “Leveraging: A Political, Economic and Societal Framework,” (Springer, 2014) I taught Gary Miroff and David Donald on Lincoln at GW’s GSPM for 12 years also. Coincidentially, I just met an MP from BC, MP Sarai, at the National Governors Association Meeting in Des Moines in July. Hope to hear from you. Best, Dave Anderson

The advice that I found most helpful in this example is the second tip given: “Employ Classic Rhetorical Devices”. I have heard this said many times in many ways, but Lincoln’s speech lended itself extremely well as an example of this advice. The power and the memorability of this speech lies in the phrases that used rhetorical devices. Since Lincoln did this so well, his speech and his ideas lived long past his own death. I also appreciated the first piece of advice that tells readers to anchor their arguments. Building credibility and gaining the trust of audience members is incredibly important whilst giving a speech, especially if your speech is asking your audience to perform a task. If they do not relate to or trust you, your request will remain untouched.

This was an excellent analysis of Abraham Lincolns speech, and gave several useful tips that every public speaker and even presenter can use is his or her own speeches to make sure that their presentation is as effective as it possibly can be. Presentations can be powerful if they are presented in the correct way.

From these 5 lessons, the ones that stood out to me were anchoring your arguments towards your audiences beliefs, the repetition of strong words and outlining the speech from past to future.

I found it incredibly interesting that it is useful to say your most important words multiple times throughout your speech. This was interesting to me because in most of my communication and literature classes, I was told not to repeat myself and only speak, or write, new ideas or concepts that will build your main points.

I found this article extremely helpful. It introduced me to ideas I ever pondered when experimenting with speeches such as repetitive use of your most important words. It also showed how rhetorical devices can enhance your speech and make it very memorable to the audience. Lastly, I learned that organizing your speech to go from past, present, then future helps grab your audiences attention and get your idea across very clearly.

2. I thought the idea of using a message that an audience already believes in, such as Abraham Lincoln quoting the Bible and Declaration of Independence, is a very effective way of capturing the audience’s attention and persuading them to agree with your message. I also believe that having a simple outline is and a clear call to action makes it easier to write a speech and easier for the audience to understand your point and decide whether they agree with you.

Recent Tweets

5 great speaking tips also apply to writing from @6minutes Lincoln speech as example + other helpful info on his site http://t.co/Xe2UboFW — Kare Anderson Nov 15th, 2011

Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln http://t.co/dwu7odEa — Bredou Alban Brice Nov 15th, 2011

Gettysburg Address Analysis: http://t.co/ap8v6VXP — Great Speaker.org Nov 16th, 2011

5 solid speech techniques presented by Andrew #Dlugan based on the Gettysburg Address http://t.co/jKjmqZ9N #speech #presentationskills — Carol Fredrickson Nov 16th, 2011

5 key lessons you can learn from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to apply to your own speeches. http://t.co/SkyR4Ah6 via @6minutes — Dennis Shiao Nov 25th, 2011

Exceptional Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln. http://t.co/b7SpIUS3 via @6minutes — Marla Zemanek Nov 26th, 2011

Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln http://t.co/yzfeiQZW #NLP #Speech — Business NLP Academy Sep 23rd, 2012

Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln http://t.co/s0gmkm7qd6 — RealTeam (@romyescarilla) Sep 25th, 2015

Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln http://t.co/Z0p6SyFjtu by @6minutes — @npeck Sep 25th, 2015

#Speech Analysis: Gettysburg Address – Abraham Lincoln (via @Pocket) 🙌 http://t.co/bLYSxkoEyl — @la1924tmclub Sep 26th, 2015

2 Blog Links

live your talk » Blog Archive » “Rhetoric Relived” – retracing the world’s great speeches at sunrise, episode 1 — Apr 15th, 2012

Concept Week 12 | Team Awesome — Nov 27th, 2012

| [ ] | [ ] | [ ] |

| [ ] | [ ] | [ ] |

| [ ] | [ ] | [ ] |

| Follow Six Minutes |

Six Minutes Copyright © 2007-2019 All Rights Reserved.

Read our permissions policy , privacy policy , or disclosure policy .

Comments? Questions? Contact us .

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg Address

Rhetorical Style

A comprehensive guide to the language of argument, Rhetorical Style offers a renewed appreciation of the persuasive power of the English language.

- By Jeanne Fahnestock

- November 19 th 2013

Perhaps no speech in the canon of American oratory is as famous as the “Dedicatory Remarks” delivered in a few minutes, one hundred and fifty years ago, by President Abraham Lincoln. Though school children may no longer memorize the conveniently brief 272 words of “The Gettysburg Address,” most American can still recall its opening and closing phrases. It has received abundant and usually reverent critical attention, especially from rhetoricians who take a functional view of discourse by always asking how an author’s choices, deliberate or not, achieve an author’s purposes. Of these many studies, the greatest is Garry Wills’s Lincoln at Gettysburg (Simon & Schuster, 1992). It leaves little unsaid about the genre, context, and content of the speech, or about the grandeur and beauty of its language, the product of Lincoln’s long self-education in and mastery of prose composition. But while the rhetorical artistry of Lincoln’s speech is uncontestable, it can also be said that its medium, the English language, was and is an instrument worthy of the artist. Among all the ways that this speech can be celebrated for its author, its moment in history, and its lasting effects, still another way is as monument to the resources of the English.

In its amazing lexicon, the largest of any living language in Lincoln’s time or ours, English is, thanks to the accidents of history, a layered language. The bottom layer, containing its simplest and most frequently used words, is Germanic. The Norman invasion added thousands of Latin words, but detoured through French to create, according to eighteenth-century British rhetoricians like Hugh Blair, a distinctive French layer in English. Throughout its history, but peaking between 1400 to 1700, words were stacked on directly from Latin and Greek to form a learned and formal layer in the language. (English of course continues borrowing from any and all languages today.) It is therefore not unusual in synonym-rich English to have multiple ways of saying something, one living on from Anglo-Saxon or Norse, another a French-tinctured option, and still another incorporated directly from a classical language. Consider the alternatives last/endure/persist or full/complete/consummate . Of course no English speaker would see these alternatives as fungible since, through years of usage, each has acquired a special sense and preferred context. But an artist in the English language like Lincoln understands the consequences in precision and nuance of movement from layer to layer. He chose the French-sourced endure at one one point in his Remarks and the Old English full at another.

Lincoln’s awareness of this synonym richness is also on display in his progressive restatement of what he and his audience cannot do at Gettysburg: they cannot dedicate — consecrate — hallow the ground they stand on . All three verbs denote roughly the same action: to set apart as special and devoted to a purpose. According to the Oxford English Dictionary , the first two came into English in the fourteenth century as adjectives and in the fifteenth as verbs, both formed from the past participle of Latin verbs. The second of these, however, has a twelfth century French cognate, consacrer , in use when French was the language of England’s rulers. The third word, hallow , comes from the Old English core and carries the strongest association of a setting apart as holy. Lincoln’s progression then goes from the Latinate layer to the core, a progression in service of the greatest goal of rhetorical style – to amplify , to express one’s meaning with emotional force. Lincoln’s series of synonyms, simply as a series, distances the living from the dead, but as a progression it rises from the formulaic setting apart with words of dedicate, to the making sacred as a church or churchyard are of consecrate , to the making holy in martyrdom of hallow . Forms of consecrate and dedicate appear again, but hallow only once, mid-speech.

Lincoln’s deftness in word choice is matched by his artistry of sentence form. Among the often-noticed features of Lincoln’s sentence style is his fondness for antithesis. This pattern is hardly Lincoln’s invention. It is one of the oldest forms recommended in rhetorical style manuals and in Aristotle’s Topics as the purest form of the argument from contraries. The formally correct antithesis places opposed wording in parallel syntactic positions: little note nor long remember/ what we say here // never forget/ what they did here.

A figure like antitheses can be formed in languages that carry meaning in inflectional endings as well as in English where word order is crucial, but other figures do not translate as easily. For example, the figure polyptoton requires carrying a term through case permutations. Had Lincoln been writing in Latin, the great concluding tricolon of the speech could have been the jangle populi, populo, populo, the genitive of the people , the ablative by the people, and the dative for the people. But English requires prepositional phrases to do what Latin does in case endings, and in this case a constraint yields a great advantage in prosody. For once listeners pick up the meter of the first and second phrase, they are prepared for the third and their satisfied expectation is part of the persuasiveness of the phrasing.

In all languages, rhetorical discourse springs from situations fixed in time and space. It responds to pressing events, addresses particular audiences and is delivered in particular places that can all be referred to with deictic or “pointing” language linking text to context. Much of the Gettysburg Address defines its own immediate rhetorical situation. Lincoln locates “we,” speaker and audience, on a portion of a great battlefield in a continuing war, and he dwells on the immediacy of this setting in space and time by repeating the word here six times (a seventh in one version, an eighth in another). This often-noted repetition is critical in Lincoln’s purpose. The speech opens in the past and closes in the future, but most of it is in the speaker and listeners’ “here” and “now” so that, held in that place and moment, a touching, a transaction can occur between the dead who gave their last full measure of devotion, and the living who take increased devotion from them.

The Gettysburg Address is profoundly the speech of a moment in our history and it is altogether fitting and proper to remember its anniversary. Yet whenever it is read or spoken it seems to belong to that moment. How is that possible? Because languages like English not only express the situation of an utterance, they also recreate that situation when the language is experienced anew. In this way, read or heard again, the Address once more performs a transaction between America’s honored dead, its author now included, and its living citizens affirming their faith in government of, by and for the people, repeating its language into the future.

Jeanne Fahnestock is Professor Emeritus, Department of English, the University of Maryland. She is the author of Rhetorical Style (Oxford, 2011), Rhetorical Figures in Science (Oxford, 1999), and co-author with Marie Secor of A Rhetoric of Argument (McGraw-Hill, 2004).

- Editor's Picks

- Linguistics

- Rhetoric & Quotations

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

[…] them from among the most famous speakers and moments in American history. Here is a paragraph from an excerpt that Oxford UP published on their website, which I have linked to often before because it’s just so good. Note that the passage as a […]

Comments are closed.

|

: and : Audio of Jim Getty's version provided by Joseph Slife, Emmanuel College Communication Dept. (Franklin Springs, Ga.) : William F. Hooley performance on 21 September 1898, , The Library of Congress : Wikimedia.org : - Stonewall Jackson's address to the 33rd Regiment : : 2/19/24 : . |

|

|

Rhetorical devices

- Logos, ethos, and pathos

- A House Divided Speech

- Language and tone

Abraham Lincoln’s “A House Divided” speech is constructed using a series of rhetorical devices, which we will outline and discuss her…

Allusions and direct references

Imagery, metaphors, and similes, enumeration and repetition.

- Rhetorical questions

An allusion is an indirect reference to people, events, or literature that the speaker finds relevant to achieving his intention. The most important allusion from the speech is “ ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ which is a quotation from the Bible attributed to Jesus Christ. The allusion is used by Lincoln as a metaphor for the division in the US (and inside the Republican Party and the government) over the issue of slavery. The speaker uses this allusion as a prediction to argue that for the union of the American states to survive, one side needs to win: ei…

The speaker creates various mental images for the audience (imagery) that make his arguments more appealing and dynamic, such as when he constructs the timber workmen analogy.

Another important example of imagery is constructed with the help of similes and metaphorical language, as the speaker describes how the meaning of popular sovereignty has been twisted to the point that it no longer has value: “Under the Dred Scott decision, ‘squatter sov…

Enumeration means listing points and arguments and can be used to give structure to a speech. In “A House Divided”, the speaker argues for his view by listing a series of events. The enumeration is marked by the speaker mentioning “the first point gained” , “the second point gained” , and “the third point gained”. Lincoln then returns to the three listed points in another enumeration that summarizes his main conclusion.

In general, repetition helps speakers make their message or arguments more memorable or draw attention to key points. For examp…

The text shown above is just an extract. Only members can read the full content.

Get access to the full Study Guide.

As a member of PrimeStudyGuides.com, you get access to all of the content.

Sign up now

Already a member? Log in

Rhetorical Devices Used In Abraham Lincoln's The Gettysburg Address

"The Gettysburg Address", a speech delivered by Abraham Lincoln, conveys its purpose through the usage of parallelism, repitition, and imagery. Those three rhetorical devices persuade the audience that respect and honor needs to be shown for those who died fighting for freedom for America. Parallelism is used to emphasize that the ones who are already dead are the ones who made the country what it is today. Lincoln states "But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate- we can not consecrate- we can not hallow- this ground." Lincoln is proving his point by being redundant with "we cannot". This helps him deliver his speech with more clarity. Lincoln also uses repitition when delivering his speech of rememberance. He says, "...shall

Juxtaposition In President Lincoln's 'Gettysburg Address'

In President Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” he effectively uses juxtaposition to make an emotional appeal so that his audience would feel a sense of remorse. In the second paragraph, Lincoln contrasts the deaths of the soldiers to a nation that might live. For example, he states that the field was “... a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.” Lincoln is saying that the soldiers fought a war so that the nation would have a chance of unifying. By using juxtaposition, Lincoln wants to evoke a sense of guilt in the audience because the soldiers gallantly fought a war just so the rest of the nation can experience the freedom and equality that they had hoped for.

Examples Of Syntax In Lincoln's Inaugural Address

With the beginning of his second term and the Civil War coming to a close, President Lincoln was burdened by a country torn apart by war. Speaking to a nation of divided loyalties, Lincoln hoped his humble approach of divine strength would convince both the North and the South to put aside their prejudices against each other and restore the shattered Union. Lincoln’s allusion, parallel structure, and syntax helped restore the nation with dignity and grace. The newly elected president began his speech by suggesting that he would not repeat what others have said in the past; little progress had been made, and the public was very aware of the negative progress the troops were making.

Rhetorical Analysis Of Lincoln's Inaugural Address

But for other words, helps to endorse this general theme, those being: care, judge, and cease. All of these words foreshadow his expectations for the future, and his feelings to come, proving he knows the nation will unite again, even if others don’t believe him, therefore allowing his main argument to gain more foot holding because it seems as though Lincoln already knows the outcome of future

Rhetorical Analysis Of Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address

President Abraham Lincoln uses a variety of rhetorical strategies in his Second Inaugural Address to pose an argument to the American people regarding the division in the country between the northern states and the southern states. Lincoln gives this address during the American Civil War, when politics were highly debated and there was a lot of disagreement. Lincoln calls for the people of America to overcome their differences to reunite as one whole nation once more. Lincoln begins his Second Inaugural Address by discussing the American Civil War and its ramifications.

Anaphora In Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address

. . shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?,” and then himself answers, “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.” The question-answer form of rhetoric, a hypophora, allows Lincoln to put forth his point of divine retribution. By allowing the audience to silently mull over the question and then affirming their thoughts, he successfully drives home his points against slavery and for unity.

Rhetoric In Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address

It’s no joke that the Civil War is America’s bloodiest war. And throughout these tumultuous times, tensions were high among all Americans. On the last legs of the Civil War, there was considerable doubt about the future of America. Would America ever recover from its harsh divide? Abraham Lincoln certainly thought so.

Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address Rhetorical Analysis

During the history of the United States there have been very respectable speakers Martin Luther King Jr. John F. Kennedy but perhaps no greater leader in American history came to addressing the country like Abraham Lincoln. In his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln gave a short speech concerning the effect of the Civil War and his own personal vision for the future of the nation. In this speech Lincoln uses many different rhetorical strategies to convey his views of the Civil War to his audience.

Rhetorical Analysis Essay On The Gettysburg Address

Specifically, 1776 the year we gained our independence from Great Britain. He reminds us where we came from and how we as people joined together in the past to defeat a common enemy. Abraham Lincoln reminds us that we came from a king that showed no mercy towards us Americans. President Lincoln takes time to show honor for all of those who fought in battle and got wounded or killed. “The Gettysburg Address” is specifically made up to this point in time in our nation’s gruesome history.

The Gettysburg Address Rhetorical Devices

In "The Gettysburg Address," Abraham Lincoln brings his point across of dedicating the cemetery at Gettysburg by using repetition, antithesis, and parallelism. Abraham Lincoln uses repetition in his speech to bring a point across and to grab the audience attention. For example, President Lincoln states, "We can not dedicate--we can not consecrate-- we can not hallow-- this ground." Abraham Lincoln is saying the Gettysburg cannot be a holy land since the ones that fought there will still be remembered, and Lincoln is assuming that the dead and brave that fought would still want Gettysburg to improve on more.

Ethos In The Gettysburg Address

One of the most famous speeches in the history of the United States is the Gettysburg Address, delivered by Abraham Lincoln on November 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The speech is directed to the American citizens and the soldiers to gain their support; Lincoln also wanted to lead the people to peace and prosperity. The main focus of the speech was to honor the soldiers that fought in the Battle of Gettysburg and to emphasize the importance of liberty. The tone of the speech is extremely hopeful in such a way that he hopes the audience will live a peaceful life.

Rhetorical Analysis Of Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address was intended to be an argument to persuade. Abraham Lincoln was inspiring his troops because morale was low after the Battle of Gettysburg. They need motivation to keep fighting. Lincoln used logos by explaining that because people gave their lives defending what they believed in, the living should finish the job the dead started. By talking about the fellow soldiers who died at Gettysburg, Lincoln appeals to the pathos of his listeners.

Alliteration In The Gettysburg Address

In “The Gettysburg Address”,Abraham LIncoln implements alliteration, parallelism, and repetition throughout his writing to remember the men that died at Gettysburg, and to motivate the people of the United States to continue the work of the dead, and to give the dead meaning. In his speech, Abraham Lincoln utilizes alliteration, in his first sentence, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth”, he uses the same sound in “Four score”, “fathers”, and “forth”, he does this to reinforce the meaning, it unifies his ideas, and helps him introduce the topic he is going to talk about. He talks about what the country was founded on, which is equality.

Metaphors In The Gettysburg Address

Throughout the speech, Lincoln seldom utilizes dividing diction such as “you”, “I” or “them” that implies that the people, and even the speaker, are separate from one another. Instead, he utilizes unifying terms, such as in “We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live”(Lincoln, #). Numerous times throughout this section the term “we” can be seen, which Lincoln used specifically as it is a unifying term. The term brings together the speaker and the audience as one, leaving no room for

Rhetorical Analysis Of The Gettysburg Address

Lincoln makes a reference to our founding fathers at the start of his speech to remind his audience of how our nation started. Giving a description of the origin of our country depicts the purpose of America's existence. A place that was once united against one cause has become a place that is divided and against each other. Lincoln also states, "that all men are created equal" in the same area he mentions the founding fathers to position his opinion on

Rhetorical Devices In Lincoln's Gettysburg Address

Gettysburg Address Rhetorical Devices In Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address” he is speaking to the very emotional nation after many people had just died during the Civil War, he needed to speak to nation to remind them that the sacrifices made by those in the Civil War will not be forgotten and that they must continue with what the war was fought for. He first starts off by referring to how the nation was started then continues to discuss the losses that have occurred from the Civil War and why they should move on while still remembering what the war was fought for. His strong use of rhetorical devices emphasises the goals they must aim for and reassures the nation that they are together in reconstruction by referring to events from the war to

More about Rhetorical Devices Used In Abraham Lincoln's The Gettysburg Address

Related topics.

- United States

- American Civil War

- Abraham Lincoln

- President of the United States

- United States Declaration of Independence

- Democratic Party

- All-in-one campaigning platform with:

- Call Center Software

- Inbound Calling

- AI Smart Insights

- Branching Scripts

- Patch Through Calling

- Spam Label Shield

- Predictive Dialer

- FastClick Dialer

- Auto Dialer

- Power Dialer

- Dynamic Caller ID

- Call Monitoring

- Answering Machine Detection

- Voice Broadcasting Software

- Press-1 Campaign

- Text to Speech

- Voicemail Transcription

- Robo Dialer

- Text Broadcasting Software

- URL Shortener

- Automatic Replies

- Short Codes

- Peer to Peer Texting Software

- Profanity Filter

- Text to Join

- Relational Organizing

- Email Marketing Software

- Analytics Dashboard

- Volunteer Teams

- Automated Phone Call System

- Sub Accounts

- Phone Number Verification

Case Studies

- Democrats Abroad

- Sheila for Congress

- Kentucky Democratic Party

- Political Campaign Tools Guide

- Political Microtargeting

- Texting for GOTV

- EveryLibrary

- Texting for Nonprofit Guide

- P2P Fundraising Guide

- Organizing for Change

- HOSPO Voice

- Energy and Utility

- Consulting Partners

- Integration Partners

- Data Partners

- Become a Partner

- Get out the vote

- Fundraising

- Donor retention

- Grassroots advocacy

- Read more blogs->

- Getting started

- P2P Texting Campaigns

- Call Center Campaigns

- Voice Broadcast Campaigns

- Mass Texting Campagins

- Need help? Visit our support center->

- Get Out The Vote Guide

- Nonprofit Fundraising Guide

- Texting for Nonprofits Guide

- Whitelabel SMS Call Software

- See all resources->

- Check out the community

- Become a community member

Have an account? Log In

- Political Campaign

The Most Effective Way To Write An Impactful Political Speech

Table of Contents

A while ago, I remember watching President Obama’s address at Selma, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the African-American community’s historic march for voting rights.

A President, more than any other, defined by his oratory skills, Obama has given plenty of powerful, era-defining speeches over the years, from the one that propelled him to the public eye in 2004 at the DNC to his final address as president in 2017.

But this speech at Selma was something special. It reflected the complicated history of race in the country and expressed a profound hope for the future. It was one that only the first black president of the United States could have given. And by all accounts, it was the perfect speech by virtue of bearing all the hallmarks: Style; Substance; Impact.

Even years later, watching it through a screen, one can not help but feel the solidarity that those in attendance at that 50th-anniversary event must have felt.

Now, there are a number of reasons you may be in want of a speech. After a resounding election victory. Or after a disastrous defeat. To bring an audience to their feet in celebration. Or calming them in the aftermath of a tragedy. Whatever the cause, here are the aspects you can use to construct one.

Deconstructing a great speech

Let us take a closer look at how to write a political speech through the lens of Obama’s speech at Selma:

Style When we look at the renowned orators in history, we see masters of both the written and the spoken word. Lincoln’s ten-sentence Gettysburg address holds the same weight today, despite there being no audio recording. As may the speech at Selma in the future, in the way it was masterfully constructed.

Substance Needless to say, beauty withers under a scrutinizing gaze. The same could be said for a speech. Every great feat of oration has always backed its elegant prose with a sturdy backbone that is its theme. In Selma, the theme set forth was that of racial justice.

Impact What impetus does your speech provide its listeners? What should the receiver ruminate on as they lay awake in their beds that night? That is how you will measure the impact of your speech. If the audience can take something concrete, something worthy, you will have fulfilled this condition away from the venue.

In Selma, it made the youth in the audience think – What excuse do we have not to vote when our parents and grandparents fought so hard for our right to do so ?

Now we take a deeper look at how to bring these three components to the forefront of our speech by examining each individual element. Not all of these elements may be present in all speeches, nor are they necessary, but they are helpful to have at hand.

Elements of Style

The selection of words.

Linguistic studies define the concept of “word choice” or “diction” as a critical element in communication theory.

One word can paint an entire picture. The work of word selection is the work of relating to your audience and evoking powerful imagery in their minds.

The solemnity of the occasion necessitated the use of a more formal speech by Obama but did not limit him to it. With phrases like “the fierce urgency of now” and “the roadblocks to opportunity” combined with the occasional informal language, he adeptly managed to weave more abstract concepts with the ground reality.

The tone of delivery

Speakers do not always write their own speeches. If that is the case, a speechwriter should be aware of the speaker’s mannerisms and how they talk and play to their strengths. Look at their past speeches for moments of greatest impact.

Pay attention to their tone, tenor, regional accent, and minor idiosyncrasies as they speak. If the speech is made for a specific audience, it is good to take note of local colloquialisms as well.

The structuring of sentences

The best speeches are texts that are beautiful to both hear and read. A surprisingly effective measure towards this end is to read the speech aloud in the process of writing. If it sounds natural, you are on the right path.

Obama alternates between short and long sentences, creating an almost unconscious rhythm to keep the attention of his audience throughout.

Creating an emotional beat

This, more than any other element of style, is self-evident. The work is half done if the speaker can take an audience on an emotional journey, orchestrating their highs and lows.

One way is to follow moments of levity with poignancy. Obama does this well at points in his speech, such as when he describes the provisions a marcher would need for a night behind bars, “an apple, a toothbrush, a book on government,” and follows with the enormity of the task they have set out to do.

Allusions and symbolism

Depending on how they are used, devices like symbols and allusions serve to lend a speech a level of grandeur, a level of importance beyond itself, by linking the present to past events.

In this speech, the most prominent symbol is the march itself. It is positioned as an inspiration for later similar movements, such as the one in Berlin, leading to the fall of its wall, and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa .

The march at Selma saw violence intended to dissuade protestors from carrying on. Obama makes a point to connect the suffering of marchers to the trials faced by slaves in American history through the use of terms like the “North Star,” which slaves followed in their bid for freedom in the northern states of the country.

Elements of Substance

Elements that pack a punch and instantly connect you with your audience are essential in a political speech. They are:

- Reflecting on the present.

- A conversational start.

- The core message.

- The stories and anecdotes.

Let’s read on to learn them in detail.

Reflecting the present

Any political speech should hold up a mirror to the issues and happenings of the present. By showing that you understand these issues, you will put yourself in good stead to talk about solutions to them.

Allow your audience to trust you. That will occur when they realize that you and they are one and the same and that what they see is what you see.

A conversational start

It is often the case that you should ease into the topic of the day.

Start off with something one would say in a conversation. Avoid a grandiose tone or statement at the outset. If it sounds cheesy, you risk losing the audience’s interest. Find something natural to say that holds meaning to the voters so that the listeners do not think it is a rehearsed piece of text. Obama starts by showing his admiration for the previous speaker.

The core message

The takeaway from your speech may just be one short soundbite for a listener. Let that soundbite be the core message of the speech .

Time it so that the message hits the audience at the peak of their interest. Once hooked, the audience will open themselves up to what you have to say.

The stories and anecdotes

Speaking of events in your life or in the lives of others: loved ones, constituents, or people you look up to, can lay the tone of your speech and set the stage to relay a greater message.

A well-placed anecdote should help people relate to the speaker. Tell the audience what influences you to do the things you do. Talk about tough times that show you understand a voter’s circumstances or a grieving loved one’s pain.

Elements of Impact

Ethos, pathos, and logos.

As put forth in Aristotle’s Rhetoric , 2300 years ago, the answer to how to write a political speech may be directly traced back to these three elements:

Ethos – The credibility of the speaker as perceived by the audience. Pathos – The emotional connections you make with the audience. Logos – The sound logical argument brought forth in your speech.

By having your audience buy into your speaker, their conviction, and their argument, you can leave a lasting impact. We can see ethos, pathos, and logos at work in the elements of style and substance as well.

By merit of being the first black president, Obama had established a level of ethos before even stepping on the stage. A further point of ethos within his speech is in the opening paragraph, where he calls John Lewis, a congressman who was a leader in the Selma march, “a personal hero,” establishing that Obama was a supporter of the struggle for civil rights.

Pathos can be found in the imagery evoked by the President throughout the speech. The telling of men and women who marched for their rights, steadfast in spite of “the gush of blood and splintered bone,” helped the audience identify with the courage of the marchers.

In his speech, he invokes logic to denounce the cynicism that he feels is rampant among youth today. He states that the march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery could only happen because of the belief of marchers in the fundamental ability of the country to change for the better, such as in this line: “If you think nothing has changed in the past 50 years, ask someone who lived through the Selma or Chicago or Los Angeles of the 1950’s”

The build-up and repetition

Every speech should steer toward the central idea that serves as its backbone. Build up toward that idea through every anecdote or statistic you share. The audience’s mind may wander. The use of repetitions will enforce your idea in their minds. Studies in psychology suggest that repetition enhances cognitive processing and aids in information retention.

Here, repetition is used time and again to underline and explain various ideas in Obama’s speech, such as in this line where he underscores the qualities that he believes his country has, “The idea of a just America, a fair America, an inclusive America, a generous America.”

The note to end on

Depending on how you played your cards, this could be the point of the speech where you leave the most impact. Here, you can choose to twist the knife or administer the antidote.

As the speech nears its conclusion, impress upon the listeners the salient points of your speech. Make them think. And then conclude on a plaintive note or a joyous one:

“We honor those who walked so we could run. We must run so our children soar. And we will not grow weary. For we believe in the power of an awesome God, and we believe in this country’s sacred promise.”

Once done, It is time for the speaker to retire and the audience to stand at attention for perhaps a moment longer, spellbound.

And that is how every great speech inevitably ends.

Featured Image Source: Mikhail Nilov

Get started absolutely free!

Welcome to callhub.

Analysis Pages

- Historical Context

Rhetorical Devices in The Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln’s Appeals : Because of the enormous changes Lincoln hopes to enact through the proclamation, he makes a series of appeals to various groups. Lincoln appeals to those who would doubt the validity and loyalty of the current Union states. He appeals to the forces of the Union Army to protect the freedom of the newly emancipated slaves and to allow them to serve. Finally, he appeals to the slaves themselves to remain peaceful.

Lincoln’s Claim to Authority : Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation under unusual circumstances. The full abolishment of slavery could only occur through an act of Congress, given that slavery was protected under the Constitution. Lincoln found a temporary means to emancipate the slaves, however. By enacting his powers as commander in chief of the armed forces during a time of war, Lincoln was able to free the slaves as a wartime measure. Knowing that the legitimacy of the proclamation would be questioned, Lincoln clarifies and emphasizes his authority in the proclamation.

Lincoln’s Offer to the Confederacy : In his preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln offers the Confederacy the chance to submit and peacefully rejoin the Union. The offer requires the Confederate states to give up slavery, however. Lincoln gives his offer added emphasis by warning that slavery will be abolished by the beginning of 1863, regardless of whether the Confederacy submits or not.

Rhetorical Devices Examples in The Emancipation Proclamation:

Text of lincoln's proclamation.

"such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States..." See in text (Text of Lincoln's Proclamation)

In this paragraph, Lincoln states his plan to enlist freed slaves in the Union Army. This plan would have a twofold effect: the newly freed slaves would receive employment; and the Union Army would receive a much-needed replenishment of soldiers and workers. At the time, the idea of allowing black Americans to serve in the military was unprecedented. This paragraph thus extends the range of rights granted to slaves beyond mere freedom.

Subscribe to unlock »

"And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence..." See in text (Text of Lincoln's Proclamation)

With the widespread freeing of Southern slaves, there arose the threat of violent rebellions among slaves. In the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, some Southerners even accused Lincoln of trying to incite violence. In some cases, these accusations were well founded, and certain slaves did rebel against their owners. However, Lincoln foresaw such violence and attempted to prevent it in this paragraph by “enjoin[ing] upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense.”

"by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-In-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States..." See in text (Text of Lincoln's Proclamation)

Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation through unconventional means and under unusual circumstances. Lincoln’s intent was to alter the nation’s laws on slavery. One obstacle to such change was slavery’s legality under the US Constitution, whose rulings may only be shaped by acts of Congress. Lincoln’s solution was to issue the proclamation through the powers granted to him as commander in chief during a time of war. Lincoln emphasizes his own authority in issuing the proclamation in order to strengthen its effects.

"by proclamation..." See in text (Text of Lincoln's Proclamation)