- Open access

- Published: 04 March 2019

Organ transplantation in the modern era

- Dmitri Bezinover ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4384-8899 1 &

- Fuat Saner 2

BMC Anesthesiology volume 19 , Article number: 32 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

47 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Peer Review reports

Organ transplantation (OT) is one of most successful advances in modern medicine. For patients with end stage disease, transplantation most often provides their only chance for survival. Even before the first transplant was performed, it was clear that OT could only be successful with a multidisciplinary approach. The history of OT has involved a series of breakthroughs in medicine that has influenced all aspects of health care. As you will see, for nearly a century, the contributions of specialists in anesthesiology and critical were largely underrepresented in the worlds literature.

Short history of organ transplantation

The earliest descriptions of OT can be found in ancient Greek, Rome, Chinese, and Indian mythology involving bone, skin, teeth, extremity, and heart transplantation [ 1 , 2 ]. In the sixteenth century, Italian surgeon Gasparo Tagliacozzi used skin transplant for plastic reconstruction. He was the first to describe what we now know is an immunologic reaction when the graft is obtained from a different person. It was only at the end of nineteenth century that OT research began to be both more systematical and better documented. The first animal models (usually dogs) were developed at this time. Early in the twentieth century, French surgeon Alexis Carrel (who later move to the US) developed a new method for vascular anastomoses. Dr. Carrel performed several successful kidney transplants in dogs, developed an approach for vessel reconstruction, and began the practice of cold graft preservation. In 1912 Dr. Alexis Carrel was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his pioneering work [ 3 ]. The first human to human transplant was performed in 1933 in the Soviet Union by the Ukrainian surgeon U.U. Voronoy. The blood group mismatched graft was obtained six hours after the donor’s death and although the patient survived two days, the graft never produced urine [ 3 , 4 ]. Despite significant surgical developments, OT was not very successful due to a lack of knowledge in immunology.

The next significant breakthrough in OT came as a result of the work of the British biologist Sir Peter Brian Medawar. His specialty was immunology. During World War II, he worked in the Burn Unit of Glasgow Hospital and investigated problems associated with skin homograft transplantation. For his research on graft rejection and acquired immune tolerance, Dr. Medawar was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1960 and is considered the father of transplantation.

Between 1951 and 1952, Hume et al., performed nine kidney transplants at the Brigham Hospital in Boston [ 5 ]. Despite the use of cortisone for immunosuppression, all grafts were rejected. This problem was successfully overcome by Dr. Thomas Murray who, in identical twins, performed the first successful kidney transplant. The recipient survived 8 years with normal graft function. Dr. Murray received the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1990. This first success sparked significant enthusiasm in researchers and clinicians in the field of OT. In 1963, after extensive experimental work in animal models, Dr. James Hardy performed the first lung transplant in Jackson, Mississippi. The patient survived for 18 days without any evidence of rejection. Internationally, over the next 10 years, a number of lungs were transplanted. They all had poor outcome related primarily to problems with the healing of surgical anastomoses. The first attempt at liver transplantation occurred in 1963 by Dr. Thomas Starzl, and in 1967, he completed the first successful liver transplant at the University of Colorado. One year later, the first European liver transplant was performed by Dr. Roy Calne in England. Also in 1967, Dr. Christiaan Barnard transplanted the first human heart in South Africa. The recipient was 53 years old and survived for 18 days. Over the next 12 months, more than 100 heart transplants were performed worldwide [ 6 ]. Unfortunately, overall survival was poor primarily due to the lack of effective immunosuppression.

In the 1950s, the first attempts at immunosuppression for kidney transplantation involved total irradiation and was met with some degree of success [ 7 , 8 ]. The use of chemical immunosuppression, initially with 6-mercaptopurine and then with combination of azathioprine and steroids, avoided the problems associated with irradiation and improved outcomes significantly. It was the discovery of cyclosporine in 1976, and its introduction in clinical practice in 1984, that dramatically changed the landscape of OT resulting in an increased one-year survival in both kidney and liver transplant recipients (95 and 75% respectively). Modern immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, sirolimis, mycophenolic acid, and everolimus), allow us to currently enjoy superior outcomes and a reduction in adverse immunosuppressive effects.

The next important milestone in the development of OT was the founding of the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) in 1984. This organization manages all transplant activities in the US including the maintenance of a national transplant list for all types of transplantation, data collection, and coordination of educational activities. There are a number of organizations in Europe and Asia with similar responsibilities.

Despite significant contributions in the success of OT, the role of Anesthesia and Critical Care in OT has not always been recognized. As well-known as the names of the first transplant surgeons (Thomas Starzl, Ray Calne, and Russel Strong) are, it is unfortunate that few people are aware that Dr. Antonio Aldrete not only introduced the Postanesthesia Recovery Score and developed the first prototype of the needle for combine spinal/epidural anesthesia but also performed anesthesia for the first liver transplant. Dr. Aldrete was involved in more than 180 liver transplants and described his experience in many publications and lectures. Dr. Thomas Starzl recognized his work as extremely important for the success of transplantation but unfortunately his name is almost forgotten in the history of OT.

In 1992, a group of anesthesiologists and critical care specialists, under leadership of Dr. Yoogoo Kang from the University of Pittsburgh, proposed the creation of a multidisciplinary society to meet the educational needs of medical professionals involved in transplantation and improve the quality of care for transplant recipients. The first two meetings which focused on preoperative care, were held in Pittsburgh in 1984 and 1986. After the success of these first meetings, The International Society for Perioperative Care in Liver Transplantation was created in 1990. It was subsequently re-named The International Liver Transplantation Society (ILTS). At about the same time in Europe, Dr. John Farman founded the Liver Intensive Care Group of Europe (LICAGE). Most recently (2016) The Society for the Advancement of Transplant Anesthesia (SATA) was founded. Today, specialists in Anesthesia and Critical Care increasingly have leadership roles in national and international transplantation societies.

Specific contributions of anesthesia and critical Care in Organ Transplantation

Advances in anesthesia and critical care, primarily in preoperative evaluation and optimization, intraoperative management, and postoperative care have contributed significantly to the success of OT. The most important contributions have been made in:

Establishing evaluation and treatment protocols for transplant candidates with comorbidities including CAD, cirrhotic and alcoholic cardiomyopathy, porto-pulmonary hypertension and hepato-pulmonary syndrome, as well as recommendations for the management of hyponatremia

Introducing the use of perioperative ultrasound and intraoperative TEE monitoring

The management of coagulopathy, including recommendations on the use of viscoelastic testing and on transfusion component therapy

Evaluation and management of perioperative hemodynamic instability including post-reperfusion and vasoplegic syndromes

The management of infections in the immunosuppressed patient

Despite these contributions, transplant anesthesia as a subspecialty is rarely represented at national anesthesia meetings. The situation is similar with the major anesthesia journals. This is changing. Anesthesia and Perioperative Care for Solid Organ Transplantation is a new section in BMC Anesthesiology and was established to provide the opportunity for anesthesiologists and critical care specialists to present their work in the field of OT. The Section Editors, Drs. Saner and Bezinover have many years of experience in transplantation. They are experts in the field of perioperative care for these very challenging patients and are actively involved the transplant societies ILTS, LICAGE, and The Transplantation Society (TTS).

Challenges in organ transplantation

Many challenges remain in the field of OT and provide fertile ground for research. The primary challenge in transplantation today for all organ types is the disproportion between organ demand and organ availability. Strategies to overcome this problem include transplantation using extended criteria grafts (ECD), donation after cardiac death (DCD), the use of machine perfusion for graft preservation of inferior quality (or initially discarded) grafts, as well as the use of living donors and split liver grafts. Additional challenges involve perioperative patient care, graft survival, and optimization of immunosuppression protocols. There are several ongoing studies in these areas. There are, however, some specific challenges associated with transplantation of individual organs.

Kidney transplantation

There are several areas of research specifically aimed at increasing organ availability and survival to include: optimization of ex-vivo machine graft perfusion and protocols for using extended criteria grafts, preoperative candidate evaluation, graft and recipient matching, pretreatment of recipients (using ischemic preconditioning) and donors (using mild hypothermia) [ 9 ]. To help alleviate the shortage of kidneys for transplantation, UNOS has recently introduced a paired donation kidney transplant pilot program. This program helps people who have identified (incompatible) living donors find well-matched donors and receive a transplantation.

Liver transplantation

Several strategies have been developed to increase organ availability include living donor liver transplantation (LDLT), split liver transplantation, and utilization of ECD and DCD grafts. The regenerative ability of liver is well known, however in contrast to renal grafts, living donation of hepatic grafts is significantly more complicated and puts the donor at greater risk as well. Today, several countries have established LDLT programs with South Korea, Turkey, Japan, and the US being leaders in the field.

Split liver transplantation also offers the possibility to perform two transplantations using one donor. Unfortunately, this option is limited due to the small size of the grafts and can be used only for children and smaller adults.

Other potential options to increase graft availability is the use of ECD, DCD and initially discarded grafts. Utilization of these organs (especially DCD) is not as high as could be due to their lower quality in comparison to donation after brain death organs. There are two major problems associated with transplanting DCD grafts: primary non-function of the transplanted organ [ 10 , 11 ] and intrahepatic biliary strictures (as a result of ischemic cholangiopathy) [ 12 ] due to prolonged warm ischemia time which is unavoidable with DCD donors. Nevertheless, utilization of these grafts is growing. It has been demonstrated that machine perfusion (both normo- and hypothermic) [ 13 , 14 , 15 ] during graft preservation can significantly increase their quality, resulting in successful transplants.

Hepatic replacement therapy is also an important area of research. There are a number artificial or bioartificial systems under investigation that may be used as a bridge to transplantation. Hepatocyte transplantation (cell suspension from unused hepatic tissue) also has demonstrated some promise [ 16 ]. Currently, these systems have limited efficacy and are topics of ongoing investigations. A bioengineered liver is a future concept and is currently under intensive development [ 17 ].

Pancreas transplantation

The first successful pancreas-kidney transplant was performed in 1966 by Drs. Richard Lillehei and William Kelly at the University of Minnesota. They performed the first singular pancreas transplant in 1968. The pancreas-kidney transplant procedure is very common today due to the high incidence of diabetic nephropathy associated with diabetes mellitus. Isolated islet transplantation is being performed with increasing frequency and is the topic of much ongoing research.

Intestinal transplantation

The first attempts at transplanting intestines were performed in 60s. These initial attempts, however, were not successful with the majority patients succumbing to rejection, infections, and surgical complications. Only after introduction of cyclosporine (and later tacrolimus) did intestinal transplantation become possible. The first successful intestine transplant was performed in 1988 by Dr. E. Deltz in Germany. Intestinal transplantation can be performed alone or as a part of multi-organ procedure. Despite significant improvements in survival, rejection and cytomegalovirus infections are still significant problems. The refinement of existing immunosuppressive protocols and the development of new drugs is a priority of research in this field.

Heart and lung transplantation

The use of both DCD cardiac and pulmonary grafts was started in the US in 1993. Even though DCD hearts and lungs have been successfully transplanted, [ 18 , 19 ], the risks associated with using these lower quality grafts is very high. Graft perfusion during preservation (usually normothermic but also hypothermic) of these organs has been demonstrated to be beneficial [ 18 , 20 , 21 , 22 ].

Other approaches currently in use for cardiac transplantation is acceptance of organs with mild coronary artery disease (CAD) and the use of previously grafted hearts.

Other areas under investigation include preventing and managing chronic rejection, preventing postoperative infection and malignancy, optimization of postoperative outcome, refining surgical techniques, and improving cardiac recovery assessment of donors after hypoxemic events.

On the horizon

Xenotransplantation is not new, however, renewed interest in this area is growing and may prove to be a solution for many problems associated with organ storage. In the early 90s, Dr. Thomas Starzl performed 2 baboon to human liver transplants. There remains many unsolved physiological, microbiological, and immunological problems associated with this type of transplantation currently under investigation.

Face, uterus, and extremity transplants have recently demonstrated with some success and will likely be performed with greater frequency in the future. Certainly, the long-term outcome of these patients has to be evaluated.

The new BMC Anesthesiology section, Anesthesia and Perioperative Care for Solid Organ Transplantation, was established to provide the opportunity for specialists involved in the care of transplant patients to submit their manuscripts on these topics. We would like to invite Anesthesiologists and Critical Care specialists, as well as all other specialists involved in OT, to submit manuscripts for consideration to this new section of BMC Anesthesiology.

Abbreviations

Coronary artery disease

Donation after cardiac death

Extended criteria grafts

International Liver Transplantation Society

Living donor liver transplantation

Liver Intensive Care Group of Europe

Organ transplantation

Society for the Advancement of Transplant Anesthesia

The Transplantation Society

United Network of Organ Sharing

Shayan H. Organ transplantation: from myth to reality. J Investig Surg. 2001;14:135–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bergan A. Ancient myth, modern reality: a brief history of transplantation. J Biocommun. 1997;24:2–9.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Barker CF, Markmann JF. Historical overview of transplantation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a014977.

Article Google Scholar

Linden PK. History of solid organ transplantation and organ donation. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:165–84 ix.

Hume DM, Merrill JP, Miller BF, Thorn GW. Experiences with renal homotransplantation in the human: report of nine cases. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:327–82.

Watson CJ, Dark JH. Organ transplantation: historical perspective and current practice. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(Suppl 1):i29–42.

Murray JE, Merrill JP, Dammin GJ, Dealy JB Jr, Walter CW, Brooke MS, Wilson RE. Study on transplantation immunity after total body irradiation: clinical and experimental investigation. Surgery. 1960;48:272–84.

Hamburger J, Vaysse J, Crosnier J, ., Auvert J, Lalanne C, Hopper J: Transplantation of a kidney between nonmonozygotic twins after irradiation of the receiver. Good function at the fourth month. Presse Med 1959, 67:1771–1775.

Google Scholar

Niemann CU, Feiner J, Swain S, Bunting S, Friedman M, Crutchfield M, Broglio K, Hirose R, Roberts JP, Malinoski D. Therapeutic hypothermia in deceased organ donors and kidney-graft function. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:405–14.

Casavilla A, Ramirez C, Shapiro R, Nghiem D, Miracle K, Bronsther O, Randhawa P, Broznick B, Fung JJ, Starzl T. Experience with liver and kidney allografts from non-heart-beating donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:197–203.

D'Alessandro AM, Hoffmann RM, Knechtle SJ, Odorico JS, Becker YT, Musat A, Pirsch JD, Sollinger HW, Kalayoglu M. Liver transplantation from controlled non-heart-beating donors. Surgery. 2000;128:579–88.

Abt P, Crawford M, Desai N, Markmann J, Olthoff K, Shaked A. Liver transplantation from controlled non-heart-beating donors: an increased incidence of biliary complications. Transplantation. 2003;75:1659–63.

Dutkowski P, de Rougemont O, Clavien PA. Machine perfusion for 'marginal' liver grafts. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2008;8:917–24.

Fondevila C, Hessheimer AJ, Ruiz A, Calatayud D, Ferrer J, Charco R, Fuster J, Navasa M, Rimola A, Taura P, et al. Liver transplant using donors after unexpected cardiac death: novel preservation protocol and acceptance criteria. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2007;7:1849–55.

Compagnon P, Levesque E, Hentati H, Disabato M, Calderaro J, Feray C, Corlu A, Cohen J, Mosbah IB, Azoulay D. An oxygenated and transportable machine perfusion system fully rescues liver grafts exposed to lethal ischemic damage in a pig model of DCD liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101:e205–13.

Dhawan A, Puppi J, Hughes RD, Mitry RR. Human hepatocyte transplantation: current experience and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:288–98.

Ko IK, Peng L, Peloso A, Smith CJ, Dhal A, Deegan DB, Zimmerman C, Clouse C, Zhao W, Shupe TD, et al. Bioengineered transplantable porcine livers with re-endothelialized vasculature. Biomaterials. 2015;40:72–9.

Dhital KK, Iyer A, Connellan M, Chew HC, Gao L, Doyle A, Hicks M, Kumarasinghe G, Soto C, Dinale A, et al. Adult heart transplantation with distant procurement and ex-vivo preservation of donor hearts after circulatory death: a case series. Lancet. 2015;385:2585–91.

Erasmus ME, van Raemdonck D, Akhtar MZ, Neyrinck A, de Antonio DG, Varela A, Dark J. DCD lung donation: donor criteria, procedural criteria, pulmonary graft function validation, and preservation. Transpl Int. 2016;29:790–7.

Loor G, Howard BT, Spratt JR, Mattison LM, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Brown RZ, Iles TL, Meyer CM, Helms HR, Price A, et al. Prolonged EVLP using OCS lung: cellular and acellular Perfusates. Transplantation. 2017;101:2303–11.

Sage E, Mussot S, Trebbia G, Puyo P, Stern M, Dartevelle P, Chapelier A, Fischler M. Foch lung transplant G: lung transplantation from initially rejected donors after ex vivo lung reconditioning: the French experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:794–9.

Messer S, Large S. Resuscitating heart transplantation: the donation after circulatory determined death donor. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:1–4.

Download references

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for preparation of this papier.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University- Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA, 17033-0850, USA

Dmitri Bezinover

Department of General-, Visceral- and Transplantation Surgery, Essen University Medical Center, Hufelandstr 55, 45147, Essen, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DB performed historical research and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. FS was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dmitri Bezinover .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors are section editors for BMC Anesthesiology.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bezinover, D., Saner, F. Organ transplantation in the modern era. BMC Anesthesiol 19 , 32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-019-0704-z

Download citation

Received : 06 February 2019

Accepted : 25 February 2019

Published : 04 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-019-0704-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Anesthesiology

ISSN: 1471-2253

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 May 2021

Organ donation and transplantation: a multi-stakeholder call to action

- Raymond Vanholder ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2633-1636 1 , 2 ,

- Beatriz Domínguez-Gil 3 ,

- Mirela Busic 4 ,

- Helena Cortez-Pinto 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Jonathan C. Craig 8 ,

- Kitty J. Jager 9 ,

- Beatriz Mahillo 3 ,

- Vianda S. Stel 9 ,

- Maria O. Valentin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4381-1332 3 ,

- Carmine Zoccali 10 , 11 &

- Gabriel C. Oniscu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1714-920X 12 , 13

Nature Reviews Nephrology volume 17 , pages 554–568 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

107 Citations

29 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Renal replacement therapy

- Social sciences

Although overall donation and transplantation activity is higher in Europe than on other continents, differences between European countries in almost every aspect of transplantation activity (for example, in the number of transplantations, the number of people with a functioning graft, in rates of living versus deceased donation, and in the use of expanded criteria donors) suggest that there is ample room for improvement. Herein we review the policy and clinical measures that should be considered to increase access to transplantation and improve post-transplantation outcomes. This Roadmap, generated by a group of major European stakeholders collaborating within a Thematic Network, presents an outline of the challenges to increasing transplantation rates and proposes 12 key areas along with specific measures that should be considered to promote transplantation. This framework can be adopted by countries and institutions that are interested in advancing transplantation, both within and outside the European Union. Within this framework, a priority ranking of initiatives is suggested that could serve as the basis for a new European Union Action Plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation.

Differences in the frequency of transplantation between countries in the European Union suggest that there is room for improvement, wherein countries with low transplantation rates could learn from the experience of countries that are doing well.

Efforts to increase transplantation rates require a variety of strategies, including approaches to increasing living and deceased donation, improving coordination of the donation and intensive care unit processes, increasing graft quality and optimizing expanded donation criteria.

Education should cover the complete spectrum of society (the general population, patients and medical professionals) with specific outreach methods to under-represented communities and individuals who are health illiterate.

Infrastructural and financial barriers to transplantation should be banned.

Similar content being viewed by others

The paradox of haematopoietic cell transplant in Latin America

Cost-effectiveness of transplanting lungs and kidneys from donors with potential hepatitis C exposure or infection

Validation of a survival benefit estimator tool in a cohort of European kidney transplant recipients

Introduction.

Organ transplantation improves patient survival and quality of life and has a major beneficial impact on public health and the socio-economic burden of organ failure. In the European Union (EU), a relatively coherent and structured approach to transplantation exists, with well-developed national programmes, international schemes to facilitate organ sharing and well-defined exchange policies 1 , making Europe a leader in the field. Between 2009 and 2015, the EU operated a successful Action Plan to promote organ donation and transplantation 2 . However, transplantation rates today differ markedly between EU countries, suggesting that there remains room for improvement. To address the differences, the European Commission convened a Thematic Network coordinated by the European Kidney Health Alliance ( EKHA ), tasked with providing guidance to increase organ donation and transplantation and presenting key action points that would increase the prevalence of patients living with a functioning transplant throughout Europe. This thematic network culminated in the publication of a joint statement that recommends strategies to promote transplantation and donation in the EU and, by extension, throughout Europe 3 . Although the focus of this statement is on adult and paediatric transplantation of solid organs, many recommendations are also applicable to tissue transplantation (for example, cornea).

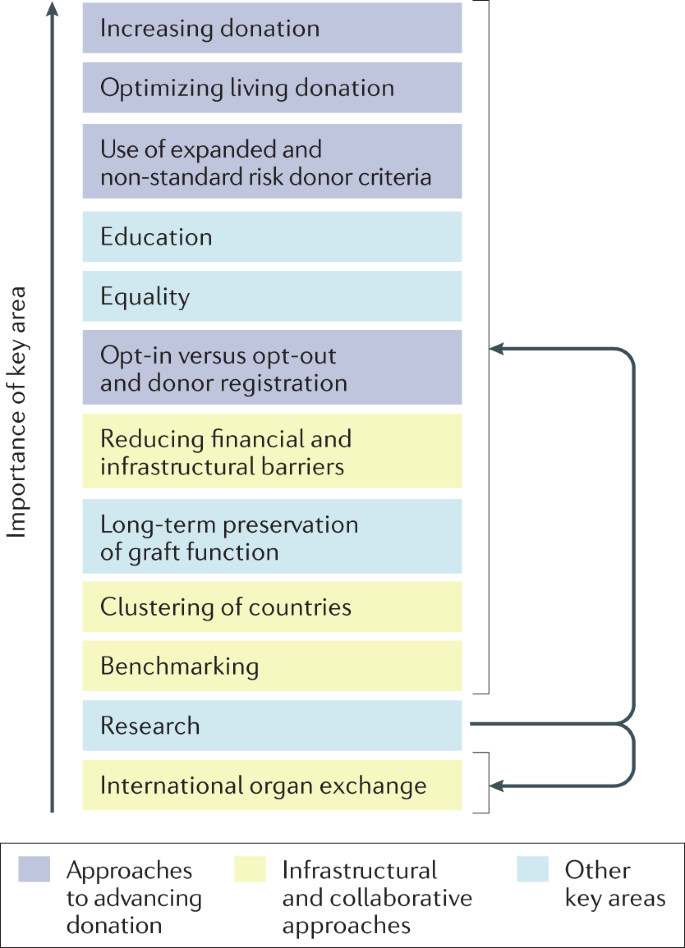

This Roadmap summarizes and builds on the Joint Statement and the experience gained from implementation of the earlier Action Plan to recommend strategies through which transplantation activities and the number of individuals living with a functioning transplant in Europe can be enhanced. We outline the challenges posed by the development and implementation of a EU-wide transplantation strategy and propose 12 key areas in which specific measures should be considered to promote transplantation, providing an overall framework that can be adopted by countries and institutions to improve rates of donation and transplantation (Fig. 1 ). These areas were selected and defined by a group of experts, including members of professional organizations, and authorities from national health-care bodies. As the Joint Statement is a product of a European Commission initiative, most of the recommendations herein are aimed at improving the current status of transplantation within the EU, but importantly these recommendations are also relevant to the 17 EU-associated countries and to regions elsewhere in the world, with some adaptations to local conditions if required.

These topics have been ranked in order of priority; however, this ranking should be considered with caution as it represents a subjective judgement by the authors of this Roadmap, possibly biased by confounding factors such as region of residence, precise involvement and responsibility in transplantation activity, personal opinion and extent of solid evidence base. Furthermore, given the variations discussed in the Roadmap, the ranking of these topics may vary between different countries or stakeholders. In addition, the topics are highly interdependent (as illustrated by colour coding) and cannot be considered in isolation. Research is linked to all topics.

Current status of transplantation in Europe

Non-communicable (chronic) diseases (NCDs) impose a substantial burden on health-care systems, economies, quality of life, employment status and social activities. In Europe, NCDs are responsible for 77% of the disease burden and 86% of deaths 4 , many of which are in young individuals 5 . Changes in population demographics and the growing prevalence of risk factors have contributed to an increase in the demand for organ replacement therapies. Artificial organ support is an option in some instances, but is only available on a large scale for kidney failure in the form of dialysis. Hence, transplantation is for many patients the only solution to restoring organ function and preventing premature death. The WHO has urged countries to progress towards self-sufficiency in transplantation, first by preventing NCDs and their progression to end-stage organ failure, but also through the provision of sufficient numbers of life-saving transplants to match their need 6 , 7 . The WHO further emphasizes that deceased donation should be developed to its maximum therapeutic potential.

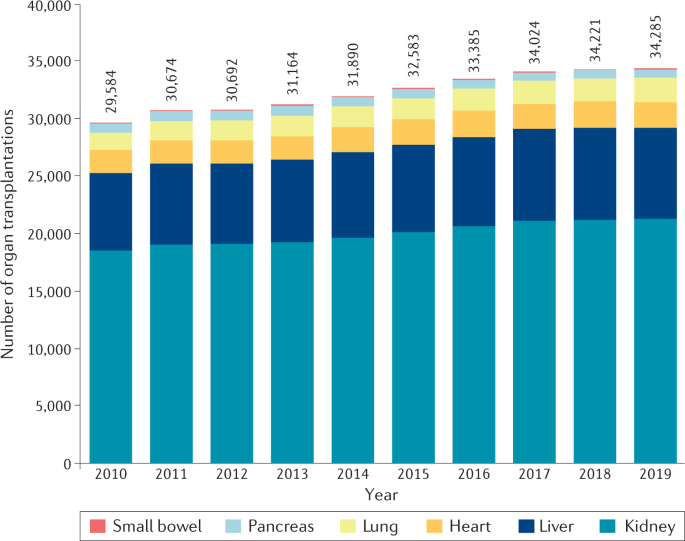

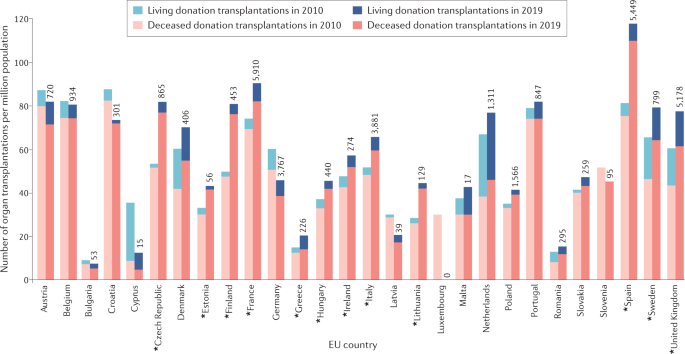

More than 34,285 solid organ transplantations were performed in the EU in 2019, 85% of which were kidney (21,235) and liver (7,900) transplants. Cardiothoracic transplantation represented 13% of activity with 2,269 hearts and 2,136 lungs transplanted, whereas pancreas (2%), small bowel and multi-visceral transplants represented only a small fraction (Table 1 ; Fig. 2 ). Although the total number of annual transplantations rose by 4,540 between 2010 and 2017, the number of annual transplantations from 2017 to 2019 increased by only 161, indicative of a stagnation in transplantation activity, possibly related to the end of the EU Action Plan in 2015 (Fig. 2 ).

As Croatia was not part of the EU in 2010–2011, the data for transplantations performed in Croatia were added to the data for the 27 EU member states for those years. The absolute total number of transplantations for each year is provided. The corresponding number per million population increased from 59 (2010) to 67 (2019). The EU Action Plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation was operational between 2009 and 2015. The marked rise in yearly transplantation rate observed particularly in the last years of the EU Action Plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation (2012–2015) seems to have levelled off in the years 2016–2019. Data were calculated based on data from the Transplant Newsletter 135 .

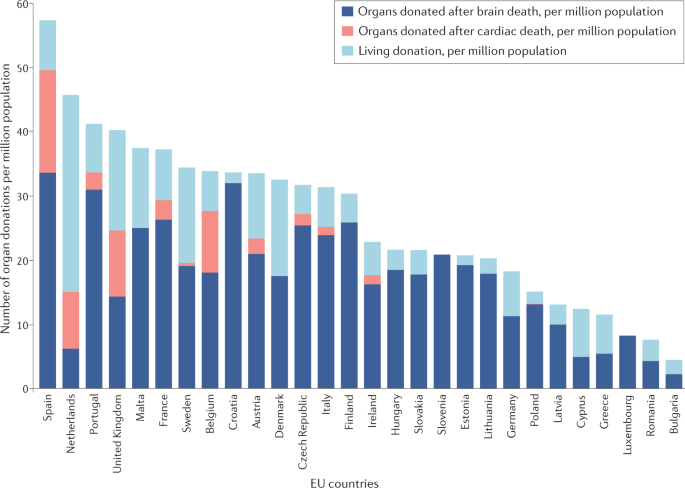

Transplantation of organs from deceased donors remains the most prevalent form of transplantation throughout the EU. Although deceased donor transplantation occurs most frequently from donors declared dead by neurological criteria (donation after brain death; DBD), donation after death declared by circulatory criteria (donation after circulatory death; DCD) contributes to transplant activity in a number of countries 8 (Table 2 ; Fig. 3 ). However, substantial variability exists in the use of DCD transplantation between EU member states. DCD is not permitted in a number of European countries because of legislative and ethical obstacles 9 , 10 , and practiced in only a few cases in many other countries 8 . In 2019, 28 of 35 European countries had an active DCD programme compared with just 10 in 2011 (ref. 10 ), but in several of these countries the DCD activity was marginal (Fig. 3 ). In 2019, DCD contributed to 17.8% of deceased donation transplantations in the EU. Living donation (almost exclusively kidney and liver), which is particularly beneficial to paediatric recipients, represents a considerable proportion of transplant activity in some but not all European countries 8 (Tables 1 , 2 ; Figs 3 , 4 ).

Substantial differences exist between EU countries in terms of their overall rates of donation but also in terms of the specific types of donation. Only 11 of the 28 countries (39%) use notable quantities of organs donated after cardiac death. Although all EU countries perform transplantation after living donation, substantial differences in the rates of living donor transplantation exist between countries. Data were calculated based on data from the Transplant Newsletter 135 .

Of 28 countries, 12 (43%) showed an increase in transplantation activity of >20% (asterisks). Although most countries tended to increase or stagnate their rates of transplantation, a few show a decrease. Also shown are the absolute numbers of transplants (from deceased plus living donors) in 2019. Data were calculated based on data from the Transplant Newsletter 135 .

The number of organ transplant procedures for the EU as a whole was 67.2 per million population in 2019, with marked differences between countries 8 , 11 (Fig. 3 ), reflecting differences in local health-care processes, efforts to develop living and deceased organ donation, available infrastructure and expertise, and economic factors 12 . Most EU member states have seen an upward trend in transplantation rates over the past decade, but some countries have seen a substantial decrease (Fig. 4 ). These decreases are in some cases influenced by external factors, such as public mistrust 13 , and have negative consequences on patient outcomes 8 , 11 .

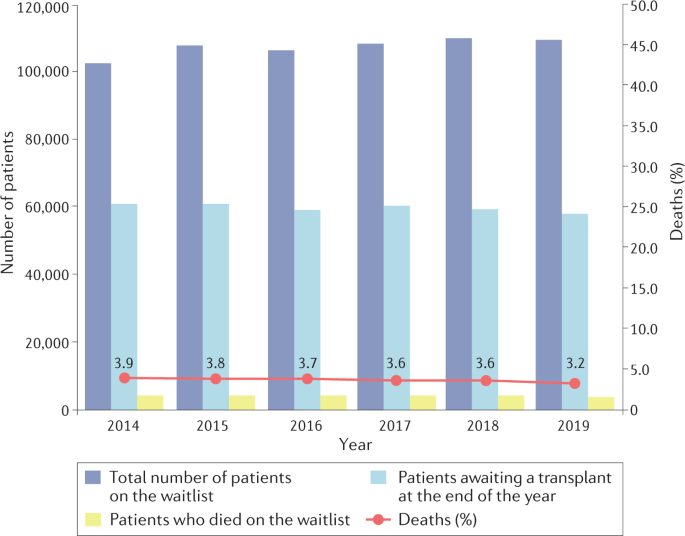

For most vital organs (liver, heart, lungs), transplantation is the only life-saving therapy. For patients with kidney failure (also known as end-stage kidney disease), which is rapidly rising in the ranked order of fatal diseases 14 , kidney transplantation offers not only a better survival and quality of life than dialysis 15 , 16 , 17 , but can be life-saving when vascular access options are lost. Yet, by the end of 2019, more than 58,000 patients were waiting for an organ transplant in the EU (Fig. 5 ). Yearly, 3–4% of those on the waiting list die before being transplanted, representing 10–11 patient deaths daily 8 . This figure is probably an underestimate, owing to incomplete data reporting in some countries. The mismatch between the need for transplants and donor supply, which excludes patients from lifesaving treatment, is exacerbated by the rising prevalence of health problems, such as diabetes mellitus and obesity, which reduces the donor pool; the presence of major public health challenges, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic; and improvements in critical care processes or car safety, which prevent deaths but also reduce the pool of deceased organ donors. The problems associated with access to donor organs are further illustrated by the small proportion of patients who receive a pre-emptive kidney transplant, which in most countries represents <10% of patients starting kidney replacement therapy 18 , necessitating a variable period on dialysis with a negative impact on survival and high associated costs 19 .

The percentage of deaths (red line) is calculated as the ratio of those who died that year while waitlisted to the total number active on the waiting list that year multiplied by 100. There was a 7% increase in the number waitlisted over this 5-year period. The percentage of deaths remained relatively stable between 3–4%. Data were calculated based on data from the Transplant Newsletter 135 .

Of note, NCDs also present a considerable health economic burden through a life-long need for consultations, medication, surgery, imaging, interventions and hospitalization. It is difficult to quantify the economic impact of organ transplantation in the absence of large-scale artificial organ treatment as an alternative option. However, for kidney failure, for which dialysis consumes at least 2% of health expenditure for only 0.1–0.2 % of the general population 1 , transplantation is by far the most cost-effective kidney replacement option, particularly from the second year post-transplantation 20 , 21 . Economic evaluations for other solid organ transplants are less straightforward. Costs associated with liver transplantation can be substantial, particularly in the context of biliary complications that can increase the duration of hospitalization and the need for diagnostic studies and further therapeutics 22 . Nevertheless, liver transplantation has been reported to be cost effective 23 in comparison with the rapidly rising costs of non-transplanted liver disease (including costs of medication, radiological procedures, and repeated and prolonged hospital admissions) 24 . Heart failure is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and places a huge burden on health-care systems; available data suggest that heart transplantation is also cost-effective in eligible adult and paediatric recipients 25 , 26 .

Unemployment among patients with chronic NCDs generates pressure not only on social security but also on productivity and buying power 27 . Transplantation can interrupt this vicious circle, although pro-active mechanisms are needed to promote socio-economic (re)integration of individuals following transplantation, as 40–80% of transplanted patients remain unemployed or permanently disabled 28 , 29 , 30 .

Finally, patients with NCDs also experience a heavy burden of polypharmacy, diet restrictions, comorbidities, and time spent in hospital and travelling to medical appointments. Transplantation restores not only organ function but also quality of life 20 , 31 . For children, transplantation also leads to improvement in development, growth, education and mental health in the recipient and in quality of life for the carer 32 .

The benefits of transplantation prompted the EU to launch the Action Plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation, which aimed to increase organ availability, enhance efficiency and accessibility of transplant procedures, and improve the quality and safety of organs intended for transplantation. It was implemented from 2009 to 2015 (refs 2 , 33 ). At the end of 2019, a 16% overall increase in transplantation rate was observed compared with 2010 8 (Table 1 and Fig. 2 ). This increase varied for different types of transplants (for example, 42% increase for lung transplantation, 17% for liver and 15% for kidney transplantation) and was primarily a result of a substantial increase in DCD 8 , suggesting that DBD and living donation may also benefit from further stimulatory interventions. Moreover, the initial rise in transplantation rate observed after 2012 seems to have somewhat levelled off in the past few years (Fig. 2 ), suggesting that the effect of the EU Action Plan has lost some momentum and that a new plan may be needed.

Data specific to kidney transplantation show that implementation of the Action Plan was associated with a rise in the total number of kidney transplantations and in the percentage of patients living with a functioning kidney graft in the EU (Supplementary Table 1 ). However, marked differences between countries are evident, underscoring the need for further action to boost transplantation rates in some regions.

Topics for action

Variations in transplantation practices and policies between European countries have led to differences in access to transplantation; in some instances, patients who may benefit from transplantation are not considered eligible (for example, owing to age or the presence of comorbidities or mental health issues) 34 . The optimal approach to increasing transplantation rates is to set well defined, ambitious goals, such as an aggregated increase in the number of EU transplantations by 10% in 10 years, complemented by specific development plans that detail the elements required to support individual countries or groups of countries according to the local conditions. This strategy should be followed by an implementation plan at a national level with internal and external auditing. Several organizations, such as the Council of Europe, have previously formulated recommendations and resolutions to increase transplantation at the institutional level (summarized in Supplementary Table 2 ). This Roadmap is complementary to those efforts and extends these initiatives by outlining a comprehensive multinational policy approach 33 , 35 , 36 . Barriers to transplantation 37 , 38 , which are often psychological and practical in nature, may be avoided through appropriate education and regulation 2 (Box 1 ).

Lessons can also be learned from countries that are performing well. For example, measures taken by Spain to increase rates of deceased organ donation 39 , 40 , 41 over recent decades have had remarkable success 8 (Supplementary Figure 1 ). These measures have included a strong emphasis on coordinating the donor process, use of a pyramidal structure to coordinate processes from local to regional and national offices, engagement of the critical care community, benchmarking, provision of guidance and continuous professional training, and the increased use of living donation, expanded donor criteria and DCD organs 39 , 40 , 41 . Regions such as Croatia, Northern Italy, the UK and France, which adapted the Spanish model to their local circumstances, also saw an increase in transplantation rates 42 , enabling these regions to focus on equality of access and approaches to optimizing outcomes and education. Other countries, such as the Netherlands, have also increased their transplantation rates substantially, largely through increasing rates of living donation (Supplementary Table 1 ).

Herein we summarize 12 key domains that informed the Joint Statement commissioned by the European Commission 3 and in which action could enable further increases in the number of donations, transplantations and patients living with a functioning transplant. These topics form the basis of a Roadmap that is intended for use by the EU, EU health-care authorities, patient associations and professional societies to guide the implementation of measures to stimulate organ donation and transplantation. Beyond increasing rates of organ donation and transplantation, the involved communities should do their utmost to maximize the longevity of transplanted organs, which is an absolute priority for the recipients 43 , 44 . To guide implementation of strategies that address each of these areas, we have ranked the 12 key topics in order of importance (Fig. 1 ). Of note, however: this ranking should be considered with caution given that it is largely opinion based, given the variation in the extent to which each of these areas may need to be addressed differently in different countries, and the interdependent nature of the areas, such that they can only be considered and implemented together. The highly integrated nature of these areas renders it near impossible to disaggregate and quantify the potential impact of individual interventions within a topic. However, all examples provided within this Roadmap refer to countries with a high transplantation rate (>60 per million population per year).

Box 1 Non-medical barriers to transplantation

Barriers at the patient level

Attitude, role perception, motivation

Distrust of health-care professionals

Lack of knowledge

Fears and concerns

Fear of rejection or graft failure

Fear of surgery

Fear of medication or adverse effects

Previous negative experiences (self or others)

Fear for the living donor’s health

Sociocultural background

Religious reasons that oppose transplantation

Unsuitable living circumstances

Shortcomings in patient efforts or investments

Reluctance to ask potential living donors

Lack of social support

Lack of adherence or hygiene

Barriers at the level of the health-care professional

Lack of knowledge and expertise

Difficulty in selecting patients

Lack of communication skills

Barriers at the level of the health-care system

Financial barriers

Lack of support staff

Competition with other treatment modalities

Patient doing well on other treatment modalities

Adapted with permission from refs 2 , 136 , the European Kidney Health Alliance.

Increasing donation

Increasing the number and quality of donated organs is a key element in increasing donation rates. Several strategies exist to facilitate this donation process.

Maximizing the role of donor coordinators

Proper coordination of the donation process is a key element in increasing donations and optimizing outcomes. The European models that have been most successful centre around the involvement of efficient donor coordinators, who are independent of the transplantation team, and are based in each hospital that has potential for deceased donation. These coordinators have key roles in the steps leading to the traditional model of deceased donation — a process that involves potential donor selection, maintenance of the haemodynamic status of the donor and organ perfusion, diagnosis of death and communication with the family. These individuals are trained in recognizing donation opportunities in end-of-life care pathways and in providing grieving families with the psychological support required to make the often difficult decision to agree to donation. Critical to the overall success of these programmes has been the appointment of professionals who develop a proactive programme for the identification of possible donors, in close cooperation with the critical care community. Donor coordinators should receive continuous training, with special attention given to the skills required to communicate with grieving relatives and organize organ handling with minimal delay. Local networks should be supported by national and regional cells that focus more on policy and technical aspects 39 . Regular internal and external audits should be used to identify areas for improvement 39 .

Optimizing the role of intensive care professionals

Engagement with intensive care professionals is particularly important to ensure that deceased donation is always considered as an option for patients receiving end-of-life care, provided that it is appropriate and consistent with the potential donor’s wishes and values 45 , 46 . Optimizing the role of intensive care professionals in the donation process requires a number of steps, including the identification of intensivists who will champion donation in their unit and in their hospital or region as a whole as well as lead education efforts; training of all intensive care staff in approaches to identifying possible organ donors on the basis of simple triggers (that is, the identification of individuals who have died or are likely to die imminently in a condition compatible with organ donation); maintenance of organ viability until donation; ensuring timely referral to donor coordinators; and ensuring an appropriate and consistent approach to the families of potential donors 46 .

Minimizing the duration of the donation process

The time between consideration of donation opportunities and initiation of the actual donation procedure can vary considerably and can exceed 24 h sometimes substantially 47 . Hesitation in donor identification and donor handling by medical staff as well as indecision of families owing to socio-cultural, religious or educational barriers 48 all affect the duration of the donation process, as do organizational factors such as the length of the process before an organ is offered to a potential recipient, the need for additional tests and lack of timely access to surgical theatres. These delays may have adverse effects on donation by increasing the risk of donor organ deterioration or withdrawal of family consent, leading to the loss of otherwise transplantable organs. Therefore, national programmes should focus on approaches to facilitating the identification of all possible donors, the early notification of donor coordinators and work with families to reduce the rate of donation refusal 49 , thus avoiding donor loss.

Optimizing living donation

Transplantation of a kidney from a living donor offers markedly better chances for graft and patient survival than transplantation of a kidney from a deceased donor 50 , whereas living donor liver transplantation involves a similar hospital stay and survival rates to deceased donor transplantation 51 . Although practiced in almost every EU country, living donation has a variable contribution to overall transplantation activity. It is markedly low in many countries, even in those with well-established transplantation programmes, with the Netherlands and Iceland as notable exceptions (Figs 3 , 4 , Supplementary Table 1 ). Living donation remains the method of choice for infants and children, in particular for those with kidney failure, because it enables pre-emptive transplantation and avoids the need for dialysis. In the Netherlands, kidney transplantation is largely driven by living donation, making it a country with one of the highest proportion of patients on kidney replacement therapy living with a functioning transplant in the EU (Supplementary Table 1 ).

Donor safety remains paramount and should be the primary focus of any living donation programme. However, it is equally important to demystify the risks of living donation, through a uniform process of information (for both the donor and recipient) and evaluation (via an online approach if convenient) to ensure that all essential information is conveyed and understood 52 (see below and Supplementary Box 1 ). This approach will encourage expansion of living donation programmes, increasing access to transplants for patients from ethnic minorities and economically challenged backgrounds who are often disadvantaged overall in transplantation programmes (see below). Living kidney donors may have a low but increased risk of developing hypertension 53 or kidney failure 54 , and therefore robust living donor programmes should carefully select donors, include an adequate follow-up, and if needed, preventive treatment. Moreover, and in contrast to the experience of many organ donors 55 , the donation process should be financially neutral. Processes therefore need to be in place to ensure that living donors do not face out-of-pocket costs and lost wages, or difficulty securing health or life insurance 56 .

Approaches to broadening donor and recipient criteria, including the involvement of emotionally related and unrelated altruistic donors and organ-sharing schemes , enable the expansion of living donation programmes. Although sharing schemes exist in a number of EU countries such as in the Netherlands and Spain, they remain non-existent or very limited in others 8 , 57 , 58 . Of note, a number of European and cross-border organ-sharing initiatives have been implemented to redress this situation 59 , 60 .

The implementation of initiatives to encourage living donation raises organizational and ethical questions, which have been addressed in a reference toolkit developed by the European Commission and National Agencies 61 . Any common ethical framework for unrelated living donation should be regulated at an EU level to alleviate any concern that pressure may be exerted on the candidate donor to benefit an irreversibly sick person and alleviate the associated societal costs 62 .

Use of expanded donor criteria

The term ‘expanded criteria donor’ is commonly applied to donors whose clinical–demographic characteristics would have an impact on the quality of the organ and its expected longevity. The traditional definition of an expanded criteria kidney donor includes age >60 years or age >50 years with at least two of the following: a history of hypertension, serum creatinine level >1.5 mg/dl (132.6 µmol/l) or death from cerebrovascular accident 63 . However, this dichotomous definition has increasingly been replaced by risk scores to guide the categorization and use of all organs (liver, kidney, pancreas) 64 , 65 , 66 . The increased use of expanded criteria donor organs and the changing profile of the potential donor pool has led to the increased use of organs from donors with a high comorbidity burden (for example, donors with diabetes mellitus). For patients with kidney failure, these organs can improve survival compared with remaining on dialysis 67 . Dual kidney transplantation (whereby both kidneys from a donor are transplanted into a recipient) can also allow the use of organs from marginal (for example, older) donors 68 .

DCD organs have in the past been considered to yield inferior post-transplant results compared with those achieved with DBD donor organs. However, increased experience has led to the attainment of appropriate post-transplantation outcomes with DCD organs 69 , 70 . Efforts can be required to overcome the legal and ethical barriers to DCD transplantation, such as the absence of a legal framework regulating the cessation of therapy, and to increase the confidence of transplantation professionals in the outcomes obtained with the use of DCD organs. Advances in organ perfusion protocols may be required to better preserve DCD organ quality and prevent the unnecessary discarding of suitable organs 71 , 72 , 73 ; however, the role of in situ and ex situ preservation strategies and the type of organs that require these interventions require further study 73 .

Non-standard risk donors are defined as those with specific conditions or diseases (for example, infections or malignancies) that can potentially affect the safety of the transplant recipient. Transplantation of these organs can be appropriate provided that an individualized risk-assessment is performed and that recipients are properly selected 74 . Examples of this scenario include the use of organs with unusual anatomy but appropriate functionality (Supplementary Box 2 ), transplantation of HIV-infected grafts into recipients with HIV 75 , or transplantation of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected grafts into HCV-negative recipients — a process that is now possible with the use of direct-acting antiviral agents 73 , 76 . For heart transplantation alone, full use of all available organs from HCV-positive donors would increase the transplantation rate by about 3% 77 . Thus, the combined use of all available donor expansion measures could increase transplantation rates substantially.

EU countries that provide a legal framework for euthanasia are the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium and as of June 2021, Spain. Organ donation after euthanasia in those countries is medically possible and thus represents a further option to provide these patients with the opportunity of organ donation and to expand the donor pool 78 , 79 .

Despite satisfactory outcomes 10 , 69 , 70 , many expanded and non-standard criteria donor organs remain underused in European countries 8 , 10 , 80 , 81 . An analysis from the USA demonstrated that the transplanted counterparts of >15% of unilaterally discarded donor kidneys showed a death-censored 5-year survival >85% 82 . Thus, discarded organs have the potential to contribute substantially to the donor organ pool and their use should be supported through the provision of information to health professionals about the benefit of using them and to the potential recipient, highlighting the benefits and risks of alternative choices. The rate of organ discard in Europe might be reduced by the application of risk score systems to guide the identification of suitable organs and appropriate recipients 83 .

Several countries have implemented educational tools to promote organ donation and transplantation (Supplementary Box 1 ). A more harmonized approach across the EU could result in further structural improvements.

Improving communication skills of health-care professionals

Communication training should in particular focus on professionals involved in the early stages of the deceased donation process — such as emergency and intensive care physicians and donor coordinators 45 , 84 . Communication training should cover both sides of the donation and transplantation process; donor coordinators and professionals in intensive care should be trained in approaches to communicating with the families of possible donors, whereas transplantation professionals should be trained in approaches to communicating with potential recipients in an informative and efficient way. Information on the benefits and practical aspects of transplantation should be embedded in the curricula of all health practitioners, from medical students to postgraduate teaching of specialists and general practitioners (Supplementary Box 1 ). Specific involvement of health-care professionals trained in patient education as part of the treating team is extremely helpful.

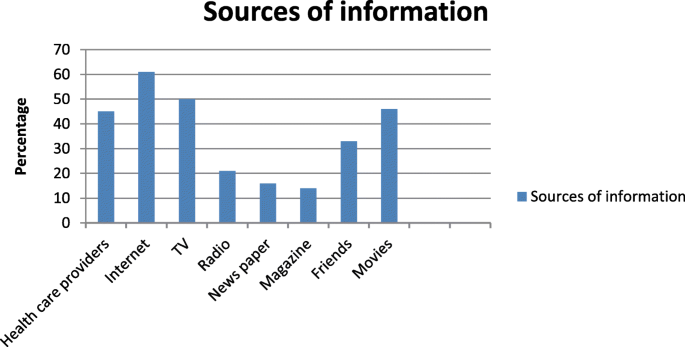

Education of the public

Insufficient public awareness of organ donation and transplantation 85 , 86 , including the concept of brain death 87 , necessitates continuous education. A highly efficient strategy involves use of mass and social media, and requires the building of active partnerships with journalists 41 . Education activities in schools and use of flyers or web-based tools may help to increase awareness. In Croatia, information pamphlets with answers to frequently asked questions are made available to the public, whereas in Finland, an online educational tool is provided to educate patients and the general public about kidney transplantation (Supplementary Box 1 ). The EKHA “Gift of life” campaign 88 offers advice to policy makers and citizens on approaches to promoting organ donation. This campaign stresses the need for a coordinated European approach based on appropriate legal and structural frameworks to allow individuals and professional nephrology and patient societies to promote kidney transplantation at the national policy level in an equitable way throughout Europe with respect to the local cultural background 88 . Such initiatives that focus on organ donation as a whole would further public education about the benefits and processes of transplantation.

Additional barriers that exist in economically or socially disadvantaged groups, including those with a low level of educational attainment, refugees, migrants and under-represented communities, should be specifically addressed with the help of patients, patient organizations, and minority communities, to understand attitudes and develop strategies and ensure equitable access to transplantation (see later) 39 . This aspect is particularly important as patients from these groups are generally over-represented on the transplant waiting list and under-represented in the donor population. Limited willingness to donate exacerbates the challenge of finding suitable HLA matches for kidney transplant candidates, prolonging the wait-list time, increasing the risk of mismatch, and jeopardizing long-term outcomes 89 .

Patient education and information

Limited health literacy (discussed below) and patient disinformation also deter transplantation 90 . The information provided by physicians and nurses to candidate organ recipients should discuss all treatment options, especially for kidney transplant candidates, for whom dialysis is a readily available but in many cases a less desirable alternative. Information about deceased and living donation 2 should be provided, as often no information is offered about the two options (Supplementary Table 3 ). Education about organ replacement options should be provided as patients approach organ failure and be delivered in a tailored way either in hospital, in outpatient clinics or at home (Supplementary Box 1 ). Patient records should include an explicit statement on the suitability of the patient for transplantation, including the views of the patient and, particularly in the case of living donation, the views of their next of kin. To improve long-term patient outcomes 91 , 92 , education should include lifestyle advice, particularly approaches to addressing excess weight, smoking, excessive alcohol intake and hypertension and to promoting a healthy diet and exercise.

In 2017, EKHA distributed a questionnaire to determine the satisfaction level of patients from six EU countries with the information that had been provided to them about the different types of kidney replacement therapy in the period preceding the start of those therapies 2 (Supplementary Table 3 ). Patient dissatisfaction with the quality of information provided about transplantation ranged from 11% (the Netherlands) to 45% (Greece). These data confirmed findings from a previous analysis 93 of data collected from 2010 to 2011, suggesting little change since then, and underscoring the need for streamlined European education for all transplant candidates. A centralized quality check on information delivery and patient satisfaction might encourage excellence. Not surprisingly, dissatisfaction about the information provided coincides with low application of a given practice, suggesting a self-fulfilling circle (for example, in the Netherlands, which has a high transplantation rate, patient satisfaction is also very high; however, proportionally more patients received only information on living donation, which very likely occurred because that is the preferred mode of donation in that country).

Achieving equality in transplantation requires that all suitable candidates — irrespective of their ethnicity, race, sex, education, socio-economic status, religion, health literacy, or language barriers — have an equal probability of receiving a transplant. However, inequalities are rife in medical practice 94 and deserve specific attention. Approaches to removing barriers to transplantation can in many instances be adapted to the specific needs of minority patient groups, as exemplified by the implementation of measures to increase access to transplantation for Jehovah’s Witnesses in Croatia (Supplementary Box 3 ). However, despite the existence of legal frameworks designed to prevent discrimination and ensure equitable access to health care and transplantation, in practice, access to transplantation remains extremely problematic for certain populations, especially for minority groups and immigrants, including undocumented migrants. These individuals face considerable barriers in access to health care, in particular to chronic therapies, including transplantation services. These barriers can arise from willing or unwilling institutional discrimination, the bias and prejudices of health professionals, as well as from non-familiarity of migrants with the medical model of the host country 94 , 95 . Educational approaches developed for the general public may not be appropriate for these communities, and specific efforts are required to ensure that these approaches reach affected individuals and are developed with input from the relevant populations. Comorbidities, such as diabetes, can be more prevalent in some ethnic minority populations, and negatively affect donation and transplantation rates 96 . Inequities among migrant populations are also closely linked to socio-economic status, exemplified by the well-documented associations between socio-economic status, waitlist placement and receipt of a transplant 97 . In the USA, African Americans, Hispanics and individuals of Asian ancestry are less likely than white Americans to receive a deceased donor kidney transplant 89 . In the UK, individuals of Asian and African Caribbean ancestry comprise 8% of the general population but 23% of the kidney transplant waitlist 98 , 99 . In the USA, the fact that the proportion of waitlisted patients vastly exceeds the number of available organs from donors of the same ethnicity has prompted adaptations of the kidney transplant allocation system, for example, by calculating the wait time from the start of dialysis instead of start of waitlisting, and by prioritizing the most sensitized patients 89 . These measures have reduced disparities in access to transplantation by increasing the proportion of actively waitlisted patients from under-represented communities and by decreasing inactive waitlisting of these individuals. These observations indicate that international and national authorities as well as professional organizations should provide regulations or recommendations to avoid discrimination in the selection process of donors and recipients for transplantation.

Disparities in access to transplantation among under-represented communities can also arise from a lower awareness of donation and transplantation processes, religious or cultural distrust of local medical professionals, fear of racism, linguistic obstacles, a lack of awareness of service availability, financial constraints, and a lack of perception of mainly asymptomatic chronic illnesses, such as kidney failure 95 , 100 . Given the importance of ethnicity as a determinant of tissue compatibility between donor and recipient, educational programmes aimed at increasing outreach to under-represented populations and at overcoming cultural or linguistic barriers are of critical importance. Although tissue matching is less important a determinant for liver or cardiothoracic transplantation than for kidney transplantation, the cultural and societal concerns are also evident in this setting.

Other subgroups, such as infants and highly sensitized individuals, also experience barriers to transplantation. Dedicated transplantation programmes, such as those that focus on identifying donor organs of appropriate size or on detecting appropriate donors using specific cross-matching methods, are needed 101 .

Finally, women are more likely to become a living donor than to receive a living organ donation 102 . Moreover, transplant recipients — irrespective of whether the organ is from a living or deceased donor — are predominantly male, especially for kidney transplants 103 . Although this inequality in access to transplantation might reflect a sex bias in the incidence of pathologies necessitating transplantation 104 , psychological and socio-economic factors also contribute to this disparity 105 , and could be prevented by addressing aspects of the transplantation system, such as inequalities in selection for waitlisting or unbalanced prioritization scores, that disadvantage women 105 .

Opt-in versus opt-out and donor registration

Considerable variation in legal frameworks for donation exists across the EU. Several EU and EU-associated countries, including Ireland, Germany, Denmark, Estonia and Switzerland, use opt-in legislation whereby consent for donation needs to be specifically sought from the donors and/or their families. Other countries apply an opt-out system (that is, consent for donation is presumed, unless the potential donors have officially registered their refusal). The Netherlands has in the past few years transitioned to an opt-out system, whereas the German government was unsuccessful in making this step. Most European countries that use an opt-out system apply a ‘soft approach’, allowing for objections by family members but supported by moral and legal leverage provided by the policy acceptance of the opt-out approach.

Compared with opt-in systems, opt-out systems are associated with higher donor rates ranging from 23.3% to 61.5% according to some studies 106 , 107 . However, a 2019 study of 35 countries found no difference in transplantation rates between opt-out and opt-in systems 108 . Multivariate analyses performed as part of that study showed that opt-out systems were independently predictive of lower rates of living donation. The divergent findings of studies that have compared opt-in and opt-out policies may be attributable to residual confounding resulting from differences in definitions, the selection of countries analysed, the period of analysis, or the choice of adjustment factors. Although there seems to be a gradual shift towards the use of opt-out systems, available data suggest that this approach as such is not sufficient to increase transplantation rates, and thus the adoption of opt-out legislation should be accompanied by other measures 109 , such as all those outlined in this Roadmap. In addition, simplified donor registration procedures such as those applied in Italy (Supplementary Box 4 ) offer an approach to encouraging donation without imposing judicial pressure 110 .

Financial and infrastructural barriers

Clinical activity related to transplantation should be subject to fair remuneration. Insufficient reimbursement to hospitals for deceased donation and organ retrieval is a major issue in some countries and may adversely affect donation rates. In many countries, the reimbursement for different kidney replacement therapies is disproportionate, such that dialysis is financially more rewarding than transplantation for care providers.

In the USA, for example, patients who receive dialysis at units managed by for-profit organizations have a lower chance of undergoing transplantation than patients treated at not-for-profit units 111 , 112 . Although difficult to extrapolate these findings to the EU, this suggests that the current imbalance in financial yield between different kidney replacement therapies can jeopardize transplantation rates, but also that differences in economic models governing health care should be considered by health-care administrations to incentivize transplantation over other approaches. For example, additional reimbursement could be given to units that have achieved high rates of transplantation among their population of patients with end-stage organ failure (Supplementary Box 5 ).

Furthermore, expansion of transplantation programmes should be supported by investment in adequate infrastructure. Recommendations for optimal infrastructure requirements and staffing of transplantation and intensive care units — including optimal numbers of surgeons, operating theatres, intensive care facilities, appropriate hospitalization and outpatient follow-up facilities, and well-trained nursing and medical staff — are all urgently needed.

Long-term preservation of graft function

Long-term preservation of graft function is the most important outcome for transplant recipients 43 . Maintenance of graft function entails avoidance of damage by rejection, medication, complications, comorbidities, or damage to other organs (for example, avoiding kidney damage in heart or liver transplant recipients due to immunosuppressive medication), but also requires specific attention to fatal outcomes or complications that might jeopardize future transplantation procedures (such as opportunistic infections, malignancy, cardiovascular disease, post-transplantation diabetes mellitus) 50 , 113 . In the first 10 years after transplantation mortality is substantially higher than that of the general population, at around 40% 114 , with a similar percentage of fatalities over the subsequent 10 years 50 , 115 . In addition, at least 15% of survivors lose function of the transplanted organ per decade 116 . Of note, despite a consistent improvement in kidney graft survival in the first 5 years post-transplant between 1986 and 2015, graft survival after the fifth year of transplantation has not substantially changed over time 116 .

Several aspects of the transplantation process should be addressed to maximize the likelihood of transplant survival. Cold ischaemia time is an important modifiable risk factor for poor transplant outcomes 117 , 118 , 119 , and it is imperative that transplantation logistics are constantly reviewed and improved to keep cold ischaemia time as short as possible. Controlling organ fibrosis may be one of the few solutions to preventing long-term graft loss, but therapeutic solutions to tackle this problem are scarce 120 . For recipients of kidney transplants experiencing graft loss, timely and uncomplicated transition onto dialysis is essential, as mortality is high in the period of dialysis (re-)initiation 121 . Non-adherence to medication is a major contributor to graft loss 122 , 123 and interventions that augment adherence increase graft survival 124 . Monitoring markers of immunosuppression can also help to individualize immunosuppressive therapy to maximize drug efficacy and minimize toxicity 125 , 126 .

A critical consideration for paediatric transplant recipients is their transition to adult transplantation clinics. This transition period can be associated with reduced compliance related to the change in environment, as differences in the approach and philosophy of adult transplantation clinics may be perceived as inhospitable by adolescents who are often psychologically and socially vulnerable 127 .

A significant number of graft-survival years are lost when young donor kidneys are transplanted into older recipients and vice versa 128 . Matching the life expectancy of the intended recipient with the projected life span of the transplant is likely to maximize graft survival and cost savings 128 . Complex algorithms are required to ensure optimal matching and account for differences in population demographics. Other factors that affect long-term organ function, such as the presence of low-level preformed donor-specific HLA antibodies require further study 129 . The role of lifestyle factors and the possible role of tailored medication also deserve further consideration.

Clustering of countries

Some countries have a strong track record in living donation and others in deceased donation, but few do both well. Similarly, some may be more successful than others at transplanting specific organs. Several countries could benefit from improving their donor coordination and recruitment processes and/or from adopting or improving expanded donation criteria. Specific scenarios should be developed according to the areas that require improvement, with countries grouped according to these characteristics. Even countries that perform well overall have room for further improvement, as exemplified by Spain, which manages to improve every year upon already high transplantation rates (Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Clustering of countries with similar needs and characteristics can streamline the development of action plans that enable different strategies for each cluster. These action plans should also account for country-specific measures and include in-depth consultation with the local transplant communities, including National Competent Authorities, transplant physicians, coordinators, regulators and authorities with representatives of other countries and the EU, enabling rapid dissemination and implementation of good clinical practice. This clustering approach could group countries with specific characteristics, for example, those needing to increase living donation compared with rates of deceased donation, or those where expanded donation criteria or donation overall could be enhanced.

Benchmarking

The optimization of transplantation programmes necessitates continuous assessment with external audits and comparison of their efficiency with peer programmes 130 . A uniform registration process and quality control system for organ donation and transplantation throughout Europe is necessary to enable this benchmarking. Transparency of hospitals in reporting their performance for access to and outcomes of transplantation is essential 112 . It is imperative that pan-European transplant registries are established for each organ, to enable benchmarking and ensure that comparable results are achieved across the EU. These comparisons would inform the specific areas for development and address local factors to ensure equitable access to transplantation and to optimize outcomes across Europe. Initiatives that enable comparisons of organ donation and transplantation rates between countries, similar to that developed by the Council of Europe Committee on Organ Transplantation, can help to stimulate countries that are seeking to achieve best practices 131 . Studying the approaches of the best performers will identify a number of critical factors for success, which can then be implemented elsewhere 132 .

Specific frameworks that promote and guide appropriate evidence-based decision making in the context of transplantation should be facilitated and supported. Recommendations might include but should not be limited to criteria for acceptance of patients on the waiting list; adequate follow-up post-transplantation; criteria for DCD transplantation; standards for transplant centres to achieve a well-functioning programme supported by adequate infrastructure; and optimal conditions for donor organ recovery. The application of European recommendations should be based on a continuously audited pan-European platform but allow adaptations according to the situation of individual countries. In Spain, benchmarking of different elements of the transplantation process is one of the cornerstones of its success 39 .