Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

- Second Opinion

- Research & Innovation

- Patients & Families

- Health Professionals

- Recently Visited

- Segunda opinión

- Refer a patient

- MyChart Login

Healthier, Happy Lives Blog

Sort articles by..., sort by category.

- Celebrating Volunteers

- Community Outreach

- Construction Updates

- Family-Centered Care

- Healthy Eating

- Heart Center

- Interesting Things

- Mental Health

- Patient Stories

- Research and Innovation

- Safety Tips

- Sustainability

- World-Class Care

About Our Blog

- Back-to-School

- Pediatric Technology

Latest Posts

- Menstruation, Birth Control, Mental Health Top Team USA Female Athletes’ Research Agenda

- Two Sisters Return to the Bay Area to Work Together in the Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services

- Heart-Lung Transplant Patient Going Strong, Reaching Dreams at 16-Year Mark

- Stanford Children’s Care Teams Invited to 49ers Training Camp as a Token of Gratitude

- Fortune Smiles on Couple Trying to Build a Family

Health Hazards of Homework

March 18, 2014 | Julie Greicius Pediatrics .

A new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education and colleagues found that students in high-performing schools who did excessive hours of homework “experienced greater behavioral engagement in school but also more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives.”

Those health problems ranged from stress, headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems, to psycho-social effects like dropping activities, not seeing friends or family, and not pursuing hobbies they enjoy.

In the Stanford Report story about the research, Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Experimental Education , says, “Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good.”

The study was based on survey data from a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in California communities in which median household income exceeded $90,000. Of the students surveyed, homework volume averaged about 3.1 hours each night.

“It is time to re-evaluate how the school environment is preparing our high school student for today’s workplace,” says Neville Golden, MD , chief of adolescent medicine at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and a professor at the School of Medicine. “This landmark study shows that excessive homework is counterproductive, leading to sleep deprivation, school stress and other health problems. Parents can best support their children in these demanding academic environments by advocating for them through direct communication with teachers and school administrators about homework load.”

Related Posts

Top-ranked group group in Los Gatos, Calif., is now a part of one of the…

The Stanford Medicine Children’s Health network continues to grow with our newest addition, Town and…

- Julie Greicius

- more by this author...

Connect with us:

Download our App:

ABOUT STANFORD MEDICINE CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Get Involved

- Volunteering Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

- Our Hospital

- Send a Greeting Card

- New Hospital

- Refer a Patient

- Pay Your Bill

Also Find Us on:

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Code of Conduct

- Price Transparency

- Stanford School of Medicine

- Stanford Health Care

- Stanford University

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

- Galloway, M., Connor, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.745469

- Pope, D., Brown, M., & Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and underprepared: Strategies for stronger schools and healthy, successful kids . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

When Is Homework Stressful? Its Effects on Students’ Mental Health

Are you wondering when is homework stressful? Well, homework is a vital constituent in keeping students attentive to the course covered in a class. By applying the lessons, students learned in class, they can gain a mastery of the material by reflecting on it in greater detail and applying what they learned through homework.

However, students get advantages from homework, as it improves soft skills like organisation and time management which are important after high school. However, the additional work usually causes anxiety for both the parents and the child. As their load of homework accumulates, some students may find themselves growing more and more bored.

Students may take assistance online and ask someone to do my online homework . As there are many platforms available for the students such as Chegg, Scholarly Help, and Quizlet offering academic services that can assist students in completing their homework on time.

Negative impact of homework

There are the following reasons why is homework stressful and leads to depression for students and affect their mental health. As they work hard on their assignments for alarmingly long periods, students’ mental health is repeatedly put at risk. Here are some serious arguments against too much homework.

No uniqueness

Homework should be intended to encourage children to express themselves more creatively. Teachers must assign kids intriguing assignments that highlight their uniqueness. similar to writing an essay on a topic they enjoy.

Moreover, the key is encouraging the child instead of criticizing him for writing a poor essay so that he can express himself more creatively.

Lack of sleep

One of the most prevalent adverse effects of schoolwork is lack of sleep. The average student only gets about 5 hours of sleep per night since they stay up late to complete their homework, even though the body needs at least 7 hours of sleep every day. Lack of sleep has an impact on both mental and physical health.

No pleasure

Students learn more effectively while they are having fun. They typically learn things more quickly when their minds are not clouded by fear. However, the fear factor that most teachers introduce into homework causes kids to turn to unethical means of completing their assignments.

Excessive homework

The lack of coordination between teachers in the existing educational system is a concern. As a result, teachers frequently end up assigning children far more work than they can handle. In such circumstances, children turn to cheat on their schoolwork by either copying their friends’ work or using online resources that assist with homework.

Anxiety level

Homework stress can increase anxiety levels and that could hurt the blood pressure norms in young people . Do you know? Around 3.5% of young people in the USA have high blood pressure. So why is homework stressful for children when homework is meant to be enjoyable and something they look forward to doing? It is simple to reject this claim by asserting that schoolwork is never enjoyable, yet with some careful consideration and preparation, homework may become pleasurable.

No time for personal matters

Students that have an excessive amount of homework miss out on personal time. They can’t get enough enjoyment. There is little time left over for hobbies, interpersonal interaction with colleagues, and other activities.

However, many students dislike doing their assignments since they don’t have enough time. As they grow to detest it, they can stop learning. In any case, it has a significant negative impact on their mental health.

Children are no different than everyone else in need of a break. Weekends with no homework should be considered by schools so that kids have time to unwind and prepare for the coming week. Without a break, doing homework all week long might be stressful.

How do parents help kids with homework?

Encouraging children’s well-being and health begins with parents being involved in their children’s lives. By taking part in their homework routine, you can see any issues your child may be having and offer them the necessary support.

Set up a routine

Your student will develop and maintain good study habits if you have a clear and organized homework regimen. If there is still a lot of schoolwork to finish, try putting a time limit. Students must obtain regular, good sleep every single night.

Observe carefully

The student is ultimately responsible for their homework. Because of this, parents should only focus on ensuring that their children are on track with their assignments and leave it to the teacher to determine what skills the students have and have not learned in class.

Listen to your child

One of the nicest things a parent can do for their kids is to ask open-ended questions and listen to their responses. Many kids are reluctant to acknowledge they are struggling with their homework because they fear being labelled as failures or lazy if they do.

However, every parent wants their child to succeed to the best of their ability, but it’s crucial to be prepared to ease the pressure if your child starts to show signs of being overburdened with homework.

Talk to your teachers

Also, make sure to contact the teacher with any problems regarding your homework by phone or email. Additionally, it demonstrates to your student that you and their teacher are working together to further their education.

Homework with friends

If you are still thinking is homework stressful then It’s better to do homework with buddies because it gives them these advantages. Their stress is reduced by collaborating, interacting, and sharing with peers.

Additionally, students are more relaxed when they work on homework with pals. It makes even having too much homework manageable by ensuring they receive the support they require when working on the assignment. Additionally, it improves their communication abilities.

However, doing homework with friends guarantees that one learns how to communicate well and express themselves.

Review homework plan

Create a schedule for finishing schoolwork on time with your child. Every few weeks, review the strategy and make any necessary adjustments. Gratefully, more schools are making an effort to control the quantity of homework assigned to children to lessen the stress this produces.

Bottom line

Finally, be aware that homework-related stress is fairly prevalent and is likely to occasionally affect you or your student. Sometimes all you or your kid needs to calm down and get back on track is a brief moment of comfort. So if you are a student and wondering if is homework stressful then you must go through this blog.

While homework is a crucial component of a student’s education, when kids are overwhelmed by the amount of work they have to perform, the advantages of homework can be lost and grades can suffer. Finding a balance that ensures students understand the material covered in class without becoming overburdened is therefore essential.

Zuella Montemayor did her degree in psychology at the University of Toronto. She is interested in mental health, wellness, and lifestyle.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

Does Homework Serve a Purpose?

Finding the right balance between schoolwork and home life..

Posted November 5, 2018 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Stress?

- Take our Burnout Test

- Find a therapist to overcome stress

Homework — a dreaded word that means more work and less play. The mere thought of doing additional work after a seven-hour day (that begins extremely early) can be gruesome. Not to mention, many teens have other commitments after the school day ends.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 57 percent of children between the ages of 6 and 17 years old participate in at least one after-school extracurricular activity. And that’s a good thing because youth extracurricular involvement comes with benefits such as boosting academic performance, reducing risky behaviors (i.e., drug use and drinking), promoting physical health, and providing a safe structured environment. However, tag these extracurricular activities onto the end of a school day and you’ll find that many teens don’t get home until it's dark outside.

What about the teen who works a 15- to 20-hour job on top of an extracurricular activity? The US Department of Labor reports that one in five high school students have a part-time job, and those jobs too can come with added benefits. Teens who work often learn the value of a hard-earned dollar. They learn how to manage their money, learn to problem solve, and most importantly, they learn how to work with people. Plus, a job in high school is a great way to add valuable experience to a resume.

With so many after school opportunities available for teens, it can be extremely difficult for them to balance homework with their other commitments. Oftentimes, active kids simply don’t have enough time in a day to get all that’s asked of them finished. When it comes homework, in all my years of working in the public school system, I have never seen a student jump for joy when homework was assigned. Of course, there are some who were anxious to complete the assignment, but that was more to get it off their busy plate. Which brings us to the essential question — does homework serve a purpose?

There are those who stand firm and back the claim that homework does serve a purpose . They often cite that homework helps prepare students for standardized tests, that it helps supplement and reinforce what’s being taught in class, and that it helps teach fundamental skills such as time management , organization, task completion, as well as responsibility (extracurricular activities and work experience can also teach those fundamental skills).

Another argument for homework is that having students complete work independently shows that they can demonstrate mastery of the material without the assistance of a teacher. Additionally, there have been numerous studies supporting homework, like a recent study that shows using online systems to assign math homework has been linked to a statistically significant boost in test scores. So, there you have it: Homework has a lot of perks and one of those involves higher test scores, particularly in math. But don’t form your opinion just yet.

Although many people rally for and support homework, there is another school of thought that homework should be decreased, or better yet, abolished. Those who join this group often cite studies linking academic stress to health risks. For example, one study in the Journal of Educational Psychology showed that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline.

The Journal of Experimental Education published research indicating that when high school students were assigned too much homework, they were more susceptible to serious mental and physical health problems, high-stress levels, and sleep deprivation. Stanford University also did a study that showed more than a couple of hours of homework a night was counterproductive. Think about it — teens spend an entire day at school, followed by extracurricular activities and possibly work, and then they get to end their day with two to three hours of homework. Now that’s a long day! No wonder so many of our teens are sleep-deprived and addicted to caffeine? On average most teens only get about 7.4 hours of sleep per night but according to the American Academy of Pediatrics , they need 8 to 10 hours.

Regardless of where you stand on the homework debate, a few things are certain: If homework is given, it should be a tool that’s used to enhance learning. Also, teachers should take into account the financial requirements of assignments, electronic accessibility, and they should be familiar with student needs as well as their other commitments. For example, not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework, so incomplete work may not be a true reflection of their ability—it may be the result of other issues they face outside of school.

Many of today's teens are taking college-level courses as early as the ninth and tenth grades. With the push of programs such as Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, Early College Programs, and Dual Enrollment, today’s teens are carrying academic loads that surpass past generations. The result of this push for rigor can lead to high levels of stress, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, depression , anxiety , and early burnout . Too many teens are already running on empty. With more than half of teens reporting school and homework as a primary source of their stress, it’s evident that academic pressure is becoming a burden.

On the flip side, not all students spend a lot of time doing homework. What takes one student an hour to complete may take another three hours. Too often educators don’t take this into account when assigning homework. According to the University of Phoenix College of Education teacher survey, high school students can get assigned up to 17.5 hours of homework each week. To top it off, a Today article reported that teachers often underestimate the amount of homework they assign by as much as 50%. Now that’s a huge miscalculation, and our nation's youth have to suffer the consequences of those errors.

There are definitely pros and cons to doing homework. I think the bigger question that educators need to address is, “what’s the purpose of the assignment?” Is it merely a way to show parents and administration what's going on in the class? Is it a means to help keep students' grades afloat by giving a grade for completion or is the assignment being graded for accuracy? Does the assignment enhance and supplement the learning experience? Furthermore, is it meaningful or busywork?

The homework debate will likely continue until we take a good, hard look at our current policies and practices. What side of the line do you stand on when it comes to homework? Perhaps you’re somewhere in the middle?

Please weigh in with your thoughts. I am always eager to hear students’ voices in this discussion. If you are a student, please share what’s on your plate and how much time you spend doing homework each night.

Challenge Success White Paper: http://www.challengesuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ChallengeSuc…

Cooper, H., et al. (meta analysis): https://www.jstor.org/stable/3700582?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Marzano, R., et al.: http://www.marzanocenter.com/2013/01/17/have-you-done-your-homework-on-…

NEA (National Education Association): http://www.nea.org/tools/16938.htm

Pope, Brown, and Miles (2015), Overloaded and Underprepared. (Brief synopsis here: https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/overloaded-and-underprepared-s… )

Raychelle Cassada Lohman n , M.S., LPC, is the author of The Anger Workbook for Teens .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

- EdCommunities

- NEA Foundation

Study: Too Many Enrichment Activities Harm Mental Health

By: Tim Walker , Senior Writer Published: March 31, 2024

Even before the pandemic, U.S. students were struggling with mental health. But the statistics have since become even more alarming. According to a new federal of teen health , about 1 in 5 adolescents report symptoms of anxiety or depression.

The impact of social media and bullying have, for good reason, dominated much of the discussion around this growing crisis. But there are other factors that increase student stress and anxiety that are not as widely reported, including not getting enough downtime.

Homework is at least partly to blame. Despite being under increased scrutiny over the past decade or so, homework is still a pillar of many U.S. classrooms. While educators and other experts have questioned its value, especially in the lower grades, others believe that homework can enhance instruction and keep students engaged if assigned in moderation. Too much homework, on the other hand, is something else entirely. The academic benefits can be marginal and too many assignments are a source of stress.

But what about other enrichment activities and extra-curriculars that are designed to bolster a child’s education (and, for high school students, college applications), such as sports, tutoring, clubs, before- and after-school programs. Is there such a thing as too much?

Yes, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Georgia. Too many enrichment activities can result in an “overscheduled” student, and that can have adverse effects—namely heightened stress and anxiety— particularly at the high school level.

There are only so many hours in a day. If they are consumed by extra assignments and activities, the student has less time to spend on developing non-cognitive or "soft" skills—skills that can be aided by relaxing, socializing and—yes, even sleeping.

Furthermore, the academic outcomes that homework and other enrichment activities are designed to bolster are overhyped. Beyond a certain point, the effect is “basically zero,” says Carolina Caetano, one of the study’s authors and an assistant professor of economics at the University of Georgia. Caetano and her colleagues found that students are assigned so much homework and signed up for so many extracurricular activities that the “last hour” was no longer helping to build their academic skills.

So the cognitive benefits flatline while student mental health is being jeopardized.

“It’s not that these assignments and activities have no value,” says Caetano. “But a threshold can be reached in which the effects turn negative. There's quite a lot of pressure on these kids from all corners. They’re undertaking much more than they really should when they probably should, at this point, just be spending more time with friends and just being free.”

Declining Academic Benefits, More Stress

For the study, the researchers analyzed the time diaries from 4,300 K-12 students, collected as part of the Child Development Supplement of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics . With this data, they could see how much time was spent per week on certain activities.

The researchers then compared time spent on these activities with academic achievement. They also held them up against psychological measures, such as being withdrawn, anxious or angry. This data was taken from parent surveys about their children’s behavior.

On average, children in the sample spent about forty-five minutes per day on enrichment activities, but that adds up over a typical week. At first, there is a clear connection between enrichment activities, academic achievement, and positive behaviors. But sure enough, at a certain point, the academic benefits decline while the problems in well-being begin to ratchet up.

These negative effects were visible and significant across all grade levels but were more prevalent in high schoolers—likely due to their heavier homework load and the added pressure of college admissions.

“The older kids do substantially more homework and substantially more of the academic type of activity,” Caetano explains. “The younger kids do a lot more of the sports and arts classes.”

Still, many elementary students are over-scheduled. If there was less on their plate, they may be allowed to enjoy more free time and become more adept at developing softer skills by the time they reach high school.

So what is the solution? That is tricky because over-scheduling students is a societal problem. “Homework is not assigned by parents. There are activities colleges demand in their candidates. It's not all a private decision made by the family.”

At the same time, even as educators point out the role homework plays in stress, not to mention the questionable academic value, many parents may still be hesitant to see it fall be the wayside or be dramatically scaled back. Homework can allow parents to understand what their students are learning and provides an opportunity to be more engaged in that work.

“Teachers should engage parents on this issue, educate them on the research that demonstrates that a lot of homework is not useful or healthy,” Caetano says. “And everyone—colleges, schools and parents—needs to understand the value of non-cognitive skills and how emotional well-being affects future success and happiness.”

Related Content

Stigma buster: schools look at mental health days for students, will the pandemic change homework forever, are schools ready to tackle the mental health crisis, reference s.

- 1 Election 2024: Education on the Ballot

- 2 Education Support Professionals Often First to See Student Mental Health Struggles

- 3 Recess During the Pandemic: More Important Than Ever

- 1 Resolution Ensuring Safe and Just Schools for All Students

- 2 NEA’s School Crisis Guide

- 3 ESP Webinar: Wellness Skills for Self-care and Health for Educational Support Professionals

Resources to Support Student & Educator Mental Health

Get more from, great public schools for every student.

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

We are experiencing sporadically slow performance in our online tools, which you may notice when working in your dashboard. Our team is fully engaged and actively working to improve your online experience. If you are experiencing a connectivity issue, we recommend you try again in 10-15 minutes. We will update this space when the issue is resolved.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., homework wars: high school workloads, student stress, and how parents can help.

Studies of typical homework loads vary : In one, a Stanford researcher found that more than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive. The research , conducted among students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities, found that too much homework resulted in stress, physical health problems and a general lack of balance.

Additionally, the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education , found that with the exception of nine-year-olds, the amount of homework schools assign has remained relatively unchanged since 1984, meaning even those in charge of the curricula don't see a need for adding more to that workload.

But student experiences don’t always match these results. On our own Student Life in America survey, over 50% of students reported feeling stressed, 25% reported that homework was their biggest source of stress, and on average teens are spending one-third of their study time feeling stressed, anxious, or stuck.

The disparity can be explained in one of the conclusions regarding the Brown Report:

Of the three age groups, 17-year-olds have the most bifurcated distribution of the homework burden. They have the largest percentage of kids with no homework (especially when the homework shirkers are added in) and the largest percentage with more than two hours.

So what does that mean for parents who still endure the homework wars at home?

Read More: Teaching Your Kids How To Deal with School Stress

It means that sometimes kids who are on a rigorous college-prep track, probably are receiving more homework, but the statistics are melding it with the kids who are receiving no homework. And on our survey, 64% of students reported that their parents couldn’t help them with their work. This is where the real homework wars lie—not just the amount, but the ability to successfully complete assignments and feel success.

Parents want to figure out how to help their children manage their homework stress and learn the material.

Our Top 4 Tips for Ending Homework Wars

1. have a routine..

Every parenting advice article you will ever read emphasizes the importance of a routine. There’s a reason for that: it works. A routine helps put order into an often disorderly world. It removes the thinking and arguing and “when should I start?” because that decision has already been made. While routines must be flexible to accommodate soccer practice on Tuesday and volunteer work on Thursday, knowing in general when and where you, or your child, will do homework literally removes half the battle.

2. Have a battle plan.

Overwhelmed students look at a mountain of homework and think “insurmountable.” But parents can look at it with an outsider’s perspective and help them plan. Put in an extra hour Monday when you don’t have soccer. Prepare for the AP Chem test on Friday a little at a time each evening so Thursday doesn’t loom as a scary study night (consistency and repetition will also help lock the information in your brain). Start reading the book for your English report so that it’s underway. Go ahead and write a few sentences, so you don’t have a blank page staring at you. Knowing what the week will look like helps you keep calm and carry on.

3. Don’t be afraid to call in reserves.

You can’t outsource the “battle” but you can outsource the help ! We find that kids just do better having someone other than their parents help them —and sometimes even parents with the best of intentions aren’t equipped to wrestle with complicated physics problem. At The Princeton Review, we specialize in making homework time less stressful. Our tutors are available 24/7 to work one-to-one in an online classroom with a chat feature, interactive whiteboard, and the file sharing tool, where students can share their most challenging assignments.

4. Celebrate victories—and know when to surrender.

Students and parents can review completed assignments together at the end of the night -- acknowledging even small wins helps build a sense of accomplishment. If you’ve been through a particularly tough battle, you’ll also want to reach reach a cease-fire before hitting your bunk. A war ends when one person disengages. At some point, after parents have provided a listening ear, planning, and support, they have to let natural consequences take their course. And taking a step back--and removing any pressure a parent may be inadvertently creating--can be just what’s needed.

Stuck on homework?

Try an online tutoring session with one of our experts, and get homework help in 40+ subjects.

Try a Free Session

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Scientists cook up a plan to save freshwater crocodiles from toxic cane toads

8 hours ago

Climate change raised the odds of unprecedented wildfires in 2023–24, say scientists

9 hours ago

Advanced microscopy method reveals hidden world of nanoscale optical metamaterials

New interpretation of runic inscription reveals pricing in Viking Age

10 hours ago

AI, computation, and the folds of life: Supercomputers help train a software tool for the protein modeling community

'Mirror' nuclei help connect nuclear theory and neutron stars

The atmosphere in the room can affect strategic decision-making, study finds

Coherence entropy unlocks new insights into light-field behavior

11 hours ago

Research team finds evidence of hydration on the asteroid Psyche

Scientists achieve more than 98% efficiency in removing nanoplastics from water

Relevant physicsforums posts, free abstract algebra curriculum in urdu and hindi.

2 hours ago

Incandescent bulbs in teaching

Aug 12, 2024

Sources to study basic logic for precocious 10-year old?

Jul 21, 2024

Kumon Math and Similar Programs

Jul 19, 2024

AAPT 2024 Summer Meeting Boston, MA (July 2024) - are you going?

Jul 4, 2024

How is Physics taught without Calculus?

Jun 25, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

The 'knowledge curse': More isn't necessarily better

Aug 7, 2024

Visiting an art exhibition can make you think more socially and openly—but for how long?

Aug 6, 2024

Autonomy boosts college student attendance and performance

Jul 31, 2024

Study reveals young scientists face career hurdles in interdisciplinary research

Jul 29, 2024

Transforming higher education for minority students: Minor adjustments, major impacts

Communicating numbers boosts trust in climate change science, research suggests

Jul 26, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Close Menu Search

- Recommend a Story

The Lion's Roar

May 24 Party Like It’s 1989: Lions Capture the 2024 Diamond Classic

May 24 Why Does the Early 20th Century Tend to Spark Nostalgia?

May 24 O.J Simpson Dead at 76: Football Star Turned Murderer

May 24 NAIA Bans Transgender Women From Women’s Sports

May 24 From Papyrus to Ashes: The Story of the Great Library of Alexandria

How Homework Is Destroying Teens’ Health

Jessica Amabile '24 , Staff Writer March 25, 2022

“[Students] average about 3.1 hours of homework each night,” according to an article published by Stanford . Teens across the country come home from school, exhausted from a long day, only to do more schoolwork. They sit at their computers, working on homework assignments for hours on end. To say the relentless amount of work they have to do is overwhelming would be an understatement. The sheer amount of homework given has many negative impacts on teenagers.

Students have had homework for decades, but in more recent years it has become increasingly more demanding. Multiple studies have shown that students average about three hours of homework per night. The Atlantic mentioned that students now have twice as much homework as students did in the 1990s. This is extremely detrimental to teens’ mental health and levels of stress. Students have a lot to do after school, such as spending time with family, extracurricular activities, taking care of siblings or other family members, hanging out with friends, or all of the above. Having to juggle all of this as well as hours on end of homework is unreasonable because teenagers already have enough to think or worry about.

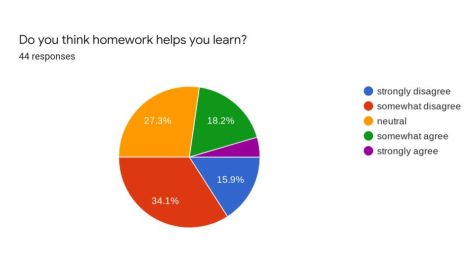

According to a student- run survey conducted in Cherry Hill West, students reported that they received the most homework in math, history, and language arts classes. They receive anywhere from 1 to 4 or more hours of homework every day, but only about 22.7% somewhat or strongly agree that it helps them learn. Of the students who participated, 63.6% think schools should continue to give out homework sometimes, while 27.3% said they should not give out homework at all. In an open-ended response section, students had a lot to say. One student wrote, “I think we should get homework to practice work if we are seen struggling, or didn’t finish work in class. But if we get homework, I think it just shows that the teacher needs more time to teach and instead of speeding up, gives us more work.” Another added, “Homework is important to learn the material. However, too much may lead to the student not learning that much, or it may become stressful to do homework everyday.” Others wrote, “The work I get in chemistry doesn’t help me learn at all if anything it confuses me more,” and “I think math is the only class I could use homework as that helps me learn while world language is supposed to help me learn but feels more like a time waste.” A student admitted, “I think homework is beneficial for students but the amount of homework teachers give us each day is very overwhelming and puts a lot of stress on kids. I always have my work done but all of the homework I have really changes my emotions and it effects me.” Another pointed out, “you are at school for most of your day waking up before the sun and still after all of that they send you home each day with work you need to do before the next day. Does that really make sense[?]”

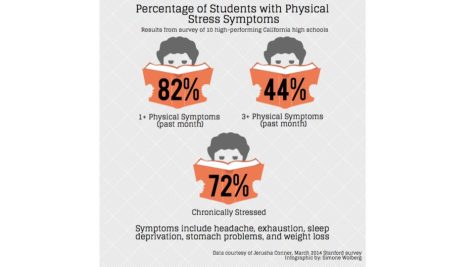

As an article from Healthline mentioned, “Researchers asked students whether they experienced physical symptoms of stress… More than 80 percent of students reported having at least one stress-related symptom in the past month, and 44 percent said they had experienced three or more symptoms.” If school is causing students physical symptoms of stress, it needs to re-evaluate whether or not homework is beneficial to students, especially teenagers. Students aren’t learning anything if they have hours of “busy work” every night, so much so that it gives them symptoms of stress, such as headaches, weight loss, sleep deprivation, and so on. The continuous hours of work are doing nothing but harming students mentally and physically.

The mental effects of homework can be harmful as well. Mental health issues are often ignored, even when schools can be the root of the problem. An article from USA Today contained a quote from a licensed therapist and social worker named Cynthia Catchings, which reads, “ heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.” Mental health problems are not beneficial in any way to education. In fact, it makes it more difficult for students to focus and learn.

Some studies have suggested that students should receive less homework. To an extent, homework can help students in certain areas, such as math. However, too much has detrimental impacts on their mental and physical health. Emmy Kang, a mental health counselor, has a suggestion. She mentioned, “I don’t think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That’s something that needs to be scrapped entirely,” she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments,” according to USA Today . Students don’t have much control over the homework they receive, but if enough people could explain to teachers the negative impacts it has on them, they might be convinced. Teachers need to realize that their students have other classes and other assignments to do. While this may not work for everything, it would at least be a start, which would be beneficial to students.

The sole purpose of schools is to educate children and young adults to help them later on in life. However, school curriculums have gone too far if hours of homework for each class are seen as necessary and beneficial to learning. Many studies have shown that homework has harmful effects on students, so how does it make sense to keep assigning it? At this rate, the amount of time spent on homework will increase in years to come, along with the effects of poor mental and physical health. Currently, students do an average of 3 hours of homework, according to the Washington Post, and the estimated amount of teenagers suffering from at least one mental illness is 1 in 5, as Polaris Teen Center stated. This is already bad enough–it’s worrisome to think it could get much worse. Homework is not more important than physical or mental health, by any standards.

What time should high school should start?

- 7:00 AM or earlier

- 7:30 AM (Current Start Time)

- After 9:00 AM

View Results

- Polls Archive

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

Mental health effects of education

Fjolla kondirolli.

1 University of Sussex, Brighton UK

Naveen Sunder

2 Bentley University, Waltham Massachusetts, USA

Associated Data

World Health Survey data is available online at https://apps.who.int/healthinfo/systems/surveydata/index.php/catalog/whs/about . Demographic and Health Surveys data is available online at https://dhsprogram.com/ . Zimbabwe census data is available online at https://www.zimstat.co.zw/ .

We analyze the role of education as a determinant of mental health. To do this, we leverage the age‐specific exposure to an educational reform as an instrument for years of education and find that the treated cohorts gained more education. This increase in education had an effect on mental health more than 2 decades later. An extra year of education led to a lower likelihood of reporting any symptoms related to depression (11.3%) and anxiety (9.8%). More educated people also suffered less severe symptoms – depression (6.1%) and anxiety (5.6%). These protective effects are higher among women and rural residents. The effects of education on mental well‐being that we document are potentially mediated through better physical health, improved health behavior and knowledge, and an increase in women's empowerment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mental health accounts for around seven percent of the global disease burden and 19% of all disability years (James, 2018 ; Rehm & Shield, 2019 ). In addition to being a valuable end in itself, mental well‐being is critical because it is a key determinant of a number of socio‐economic outcomes such as premature mortality (Graham & Pinto, 2019 ) and lower life expectancy (Wahlbeck et al., 2011 ), and higher risk of other communicable and non‐communicable diseases (Hobkirk et al., 2015 ; Prince et al., 2007 ). In terms of economic outcomes, people with lower psychological well‐being have a higher likelihood of being unemployed (Frijters et al., 2014 ), earn lower wages (Graham et al., 2004 ), and are less productive (Oswald et al., 2015 ). This makes them vulnerable to economic shocks and more likely to live in poverty (Lund et al., 2011 ).

The negative effects of poor mental health are exacerbated in low‐ and middle‐income countries due to under‐treatment. Estimates suggest that under‐treatment is around 76–90% in low and middle‐income countries as opposed to 35–50% in developed countries (Patel et al., 2010 ). Mental health is stigmatized in low‐income countries – evidence from a variety of contexts including Ethiopia (Shibre et al., 2001 ), India (Koschorke et al., 2014 ), and Nigeria (Oshodi et al., 2014 ) demonstrates that individuals suffering from poor mental health fear being discriminated against and being ostracized by society, and consequently under‐report these issues and have a lower likelihood of seeking appropriate treatment. The under‐reporting of mental health issues, coupled with low investment in mental health infrastructure and diminished availability of human resources results in a higher treatment gap in these countries (Mascayano et al., 2015 ). The high prevalence and low rates of treatment of mental disorders in developing countries creates a large welfare loss ‐ Bloom et al. ( 2011 ) estimate that by the year 2030, mental disorders are expected to lead to a loss in economic output amounting to around 20% of the global GDP. This necessitates the need to study factors that can help improve mental health. We explore the role of one such factor – education.

In particular, we examine the effect of years of education on long‐run mental health of individuals. We do so in the context of Zimbabwe. Before 1980, the country was under British colonial rule, and there were several discriminatory policies that restricted educational attainment among Black Zimbabweans. For example, primary education (grades 1–7) was free and compulsory only for White students, while Black students had to pay fees and were not required to enroll. Black students also had to take a competitive exam (for a limited number of seats) to gain admission into secondary school, while their White counterparts received automatic progression. Post‐independence (in 1980) the new government focused their efforts on improving educational outcomes, and implemented three critical reforms ‐ (1) free and compulsory primary education for all, (2) automatic progression into secondary school, and (3) the relaxing of age restrictions related to entry into primary school. These reforms benefited Black children who were of primary school‐going age at the time. Since Zimbabwean kids started school when they turned six, those who were 13 years or younger in 1980 disproportionately benefited from these policies (treatment group). Since the reform also allowed for some over‐age students to enroll in school, some children who were 14 or 15 years of age in 1980 might have also experienced some educational gains (the partially treated group). However, older individuals (16 years or above at the time) were significantly less likely to experience any such benefits, 1 and thus form our control group.