Ethical Considerations In Psychology Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Ethics refers to the correct rules of conduct necessary when carrying out research. We have a moral responsibility to protect research participants from harm.

However important the issue under investigation, psychologists must remember that they have a duty to respect the rights and dignity of research participants. This means that they must abide by certain moral principles and rules of conduct.

What are Ethical Guidelines?

In Britain, ethical guidelines for research are published by the British Psychological Society, and in America, by the American Psychological Association. The purpose of these codes of conduct is to protect research participants, the reputation of psychology, and psychologists themselves.

Moral issues rarely yield a simple, unambiguous, right or wrong answer. It is, therefore, often a matter of judgment whether the research is justified or not.

For example, it might be that a study causes psychological or physical discomfort to participants; maybe they suffer pain or perhaps even come to serious harm.

On the other hand, the investigation could lead to discoveries that benefit the participants themselves or even have the potential to increase the sum of human happiness.

Rosenthal and Rosnow (1984) also discuss the potential costs of failing to carry out certain research. Who is to weigh up these costs and benefits? Who is to judge whether the ends justify the means?

Finally, if you are ever in doubt as to whether research is ethical or not, it is worthwhile remembering that if there is a conflict of interest between the participants and the researcher, it is the interests of the subjects that should take priority.

Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented. All UK research requires ethical approval by one or more of the following:

- Department Ethics Committee (DEC) : for most routine research.

- Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) : for non-routine research.

- External Ethics Committee (EEC) : for research that s externally regulated (e.g., NHS research).

Committees review proposals to assess if the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in light of the possible risk of physical or psychological harm.

These committees may request researchers make changes to the study’s design or procedure or, in extreme cases, deny approval of the study altogether.

The British Psychological Society (BPS) and American Psychological Association (APA) have issued a code of ethics in psychology that provides guidelines for conducting research. Some of the more important ethical issues are as follows:

Informed Consent

Before the study begins, the researcher must outline to the participants what the research is about and then ask for their consent (i.e., permission) to participate.

An adult (18 years +) capable of being permitted to participate in a study can provide consent. Parents/legal guardians of minors can also provide consent to allow their children to participate in a study.

Whenever possible, investigators should obtain the consent of participants. In practice, this means it is not sufficient to get potential participants to say “Yes.”

They also need to know what it is that they agree to. In other words, the psychologist should, so far as is practicable, explain what is involved in advance and obtain the informed consent of participants.

Informed consent must be informed, voluntary, and rational. Participants must be given relevant details to make an informed decision, including the purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Consent must be given voluntarily without undue coercion. And participants must have the capacity to rationally weigh the decision.

Components of informed consent include clearly explaining the risks and expected benefits, addressing potential therapeutic misconceptions about experimental treatments, allowing participants to ask questions, and describing methods to minimize risks like emotional distress.

Investigators should tailor the consent language and process appropriately for the study population. Obtaining meaningful informed consent is an ethical imperative for human subjects research.

The voluntary nature of participation should not be compromised through coercion or undue influence. Inducements should be fair and not excessive/inappropriate.

However, it is not always possible to gain informed consent. Where the researcher can’t ask the actual participants, a similar group of people can be asked how they would feel about participating.

If they think it would be OK, then it can be assumed that the real participants will also find it acceptable. This is known as presumptive consent.

However, a problem with this method is that there might be a mismatch between how people think they would feel/behave and how they actually feel and behave during a study.

In order for consent to be ‘informed,’ consent forms may need to be accompanied by an information sheet for participants’ setting out information about the proposed study (in lay terms), along with details about the investigators and how they can be contacted.

Special considerations exist when obtaining consent from vulnerable populations with decisional impairments, such as psychiatric patients, intellectually disabled persons, and children/adolescents. Capacity can vary widely so should be assessed individually, but interventions to improve comprehension may help. Legally authorized representatives usually must provide consent for children.

Participants must be given information relating to the following:

- A statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate will not result in any consequences or any loss of benefits that the person is otherwise entitled to receive.

- Purpose of the research.

- All foreseeable risks and discomforts to the participant (if there are any). These include not only physical injury but also possible psychological.

- Procedures involved in the research.

- Benefits of the research to society and possibly to the individual human subject.

- Length of time the subject is expected to participate.

- Person to contact for answers to questions or in the event of injury or emergency.

- Subjects” right to confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Debriefing after a study involves informing participants about the purpose, providing an opportunity to ask questions, and addressing any harm from participation. Debriefing serves an educational function and allows researchers to correct misconceptions. It is an ethical imperative.

After the research is over, the participant should be able to discuss the procedure and the findings with the psychologist. They must be given a general idea of what the researcher was investigating and why, and their part in the research should be explained.

Participants must be told if they have been deceived and given reasons why. They must be asked if they have any questions, which should be answered honestly and as fully as possible.

Debriefing should occur as soon as possible and be as full as possible; experimenters should take reasonable steps to ensure that participants understand debriefing.

“The purpose of debriefing is to remove any misconceptions and anxieties that the participants have about the research and to leave them with a sense of dignity, knowledge, and a perception of time not wasted” (Harris, 1998).

The debriefing aims to provide information and help the participant leave the experimental situation in a similar frame of mind as when he/she entered it (Aronson, 1988).

Exceptions may exist if debriefing seriously compromises study validity or causes harm itself, like negative emotions in children. Consultation with an institutional review board guides exceptions.

Debriefing indicates investigators’ commitment to participant welfare. Harms may not be raised in the debriefing itself, so responsibility continues after data collection. Following up demonstrates respect and protects persons in human subjects research.

Protection of Participants

Researchers must ensure that those participating in research will not be caused distress. They must be protected from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend or harm participants.

Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than in ordinary life, i.e., participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those encountered in their normal lifestyles.

The researcher must also ensure that if vulnerable groups are to be used (elderly, disabled, children, etc.), they must receive special care. For example, if studying children, ensure their participation is brief as they get tired easily and have a limited attention span.

Researchers are not always accurately able to predict the risks of taking part in a study, and in some cases, a therapeutic debriefing may be necessary if participants have become disturbed during the research (as happened to some participants in Zimbardo’s prisoners/guards study ).

Deception research involves purposely misleading participants or withholding information that could influence their participation decision. This method is controversial because it limits informed consent and autonomy, but can provide otherwise unobtainable valuable knowledge.

Types of deception include (i) deliberate misleading, e.g. using confederates, staged manipulations in field settings, deceptive instructions; (ii) deception by omission, e.g., failure to disclose full information about the study, or creating ambiguity.

The researcher should avoid deceiving participants about the nature of the research unless there is no alternative – and even then, this would need to be judged acceptable by an independent expert. However, some types of research cannot be carried out without at least some element of deception.

For example, in Milgram’s study of obedience , the participants thought they were giving electric shocks to a learner when they answered a question wrongly. In reality, no shocks were given, and the learners were confederates of Milgram.

This is sometimes necessary to avoid demand characteristics (i.e., the clues in an experiment that lead participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for).

Another common example is when a stooge or confederate of the experimenter is used (this was the case in both the experiments carried out by Asch ).

According to ethics codes, deception must have strong scientific justification, and non-deceptive alternatives should not be feasible. Deception that causes significant harm is prohibited. Investigators should carefully weigh whether deception is necessary and ethical for their research.

However, participants must be deceived as little as possible, and any deception must not cause distress. Researchers can determine whether participants are likely distressed when deception is disclosed by consulting culturally relevant groups.

Participants should immediately be informed of the deception without compromising the study’s integrity. Reactions to learning of deception can range from understanding to anger. Debriefing should explain the scientific rationale and social benefits to minimize negative reactions.

If the participant is likely to object or be distressed once they discover the true nature of the research at debriefing, then the study is unacceptable.

If you have gained participants’ informed consent by deception, then they will have agreed to take part without actually knowing what they were consenting to. The true nature of the research should be revealed at the earliest possible opportunity or at least during debriefing.

Some researchers argue that deception can never be justified and object to this practice as it (i) violates an individual’s right to choose to participate; (ii) is a questionable basis on which to build a discipline; and (iii) leads to distrust of psychology in the community.

Confidentiality

Protecting participant confidentiality is an ethical imperative that demonstrates respect, ensures honest participation, and prevents harms like embarrassment or legal issues. Methods like data encryption, coding systems, and secure storage should match the research methodology.

Participants and the data gained from them must be kept anonymous unless they give their full consent. No names must be used in a lab report .

Researchers must clearly describe to participants the limits of confidentiality and methods to protect privacy. With internet research, threats exist like third-party data access; security measures like encryption should be explained. For non-internet research, other protections should be noted too, like coding systems and restricted data access.

High-profile data breaches have eroded public trust. Methods that minimize identifiable information can further guard confidentiality. For example, researchers can consider whether birthdates are necessary or just ages.

Generally, reducing personal details collected and limiting accessibility safeguards participants. Following strong confidentiality protections demonstrates respect for persons in human subjects research.

What do we do if we discover something that should be disclosed (e.g., a criminal act)? Researchers have no legal obligation to disclose criminal acts and must determine the most important consideration: their duty to the participant vs. their duty to the wider community.

Ultimately, decisions to disclose information must be set in the context of the research aims.

Withdrawal from an Investigation

Participants should be able to leave a study anytime if they feel uncomfortable. They should also be allowed to withdraw their data. They should be told at the start of the study that they have the right to withdraw.

They should not have pressure placed upon them to continue if they do not want to (a guideline flouted in Milgram’s research).

Participants may feel they shouldn’t withdraw as this may ‘spoil’ the study. Many participants are paid or receive course credits; they may worry they won’t get this if they withdraw.

Even at the end of the study, the participant has a final opportunity to withdraw the data they have provided for the research.

Ethical Issues in Psychology & Socially Sensitive Research

There has been an assumption over the years by many psychologists that provided they follow the BPS or APA guidelines when using human participants and that all leave in a similar state of mind to how they turned up, not having been deceived or humiliated, given a debrief, and not having had their confidentiality breached, that there are no ethical concerns with their research.

But consider the following examples:

a) Caughy et al. 1994 found that middle-class children in daycare at an early age generally score less on cognitive tests than children from similar families reared in the home.

Assuming all guidelines were followed, neither the parents nor the children participating would have been unduly affected by this research. Nobody would have been deceived, consent would have been obtained, and no harm would have been caused.

However, consider the wider implications of this study when the results are published, particularly for parents of middle-class infants who are considering placing their young children in daycare or those who recently have!

b) IQ tests administered to black Americans show that they typically score 15 points below the average white score.

When black Americans are given these tests, they presumably complete them willingly and are not harmed as individuals. However, when published, findings of this sort seek to reinforce racial stereotypes and are used to discriminate against the black population in the job market, etc.

Sieber & Stanley (1988) (the main names for Socially Sensitive Research (SSR) outline 4 groups that may be affected by psychological research: It is the first group of people that we are most concerned with!

- Members of the social group being studied, such as racial or ethnic group. For example, early research on IQ was used to discriminate against US Blacks.

- Friends and relatives of those participating in the study, particularly in case studies, where individuals may become famous or infamous. Cases that spring to mind would include Genie’s mother.

- The research team. There are examples of researchers being intimidated because of the line of research they are in.

- The institution in which the research is conducted.

salso suggest there are 4 main ethical concerns when conducting SSR:

- The research question or hypothesis.

- The treatment of individual participants.

- The institutional context.

- How the findings of the research are interpreted and applied.

Ethical Guidelines For Carrying Out SSR

Sieber and Stanley suggest the following ethical guidelines for carrying out SSR. There is some overlap between these and research on human participants in general.

Privacy : This refers to people rather than data. Asking people questions of a personal nature (e.g., about sexuality) could offend.

Confidentiality: This refers to data. Information (e.g., about H.I.V. status) leaked to others may affect the participant’s life.

Sound & valid methodology : This is even more vital when the research topic is socially sensitive. Academics can detect flaws in methods, but the lay public and the media often don’t.

When research findings are publicized, people are likely to consider them fact, and policies may be based on them. Examples are Bowlby’s maternal deprivation studies and intelligence testing.

Deception : Causing the wider public to believe something, which isn’t true by the findings, you report (e.g., that parents are responsible for how their children turn out).

Informed consent : Participants should be made aware of how participating in the research may affect them.

Justice & equitable treatment : Examples of unjust treatment are (i) publicizing an idea, which creates a prejudice against a group, & (ii) withholding a treatment, which you believe is beneficial, from some participants so that you can use them as controls.

Scientific freedom : Science should not be censored, but there should be some monitoring of sensitive research. The researcher should weigh their responsibilities against their rights to do the research.

Ownership of data : When research findings could be used to make social policies, which affect people’s lives, should they be publicly accessible? Sometimes, a party commissions research with their interests in mind (e.g., an industry, an advertising agency, a political party, or the military).

Some people argue that scientists should be compelled to disclose their results so that other scientists can re-analyze them. If this had happened in Burt’s day, there might not have been such widespread belief in the genetic transmission of intelligence. George Miller (Miller’s Magic 7) famously argued that we should give psychology away.

The values of social scientists : Psychologists can be divided into two main groups: those who advocate a humanistic approach (individuals are important and worthy of study, quality of life is important, intuition is useful) and those advocating a scientific approach (rigorous methodology, objective data).

The researcher’s values may conflict with those of the participant/institution. For example, if someone with a scientific approach was evaluating a counseling technique based on a humanistic approach, they would judge it on criteria that those giving & receiving the therapy may not consider important.

Cost/benefit analysis : It is unethical if the costs outweigh the potential/actual benefits. However, it isn’t easy to assess costs & benefits accurately & the participants themselves rarely benefit from research.

Sieber & Stanley advise that researchers should not avoid researching socially sensitive issues. Scientists have a responsibility to society to find useful knowledge.

- They need to take more care over consent, debriefing, etc. when the issue is sensitive.

- They should be aware of how their findings may be interpreted & used by others.

- They should make explicit the assumptions underlying their research so that the public can consider whether they agree with these.

- They should make the limitations of their research explicit (e.g., ‘the study was only carried out on white middle-class American male students,’ ‘the study is based on questionnaire data, which may be inaccurate,’ etc.

- They should be careful how they communicate with the media and policymakers.

- They should be aware of the balance between their obligations to participants and those to society (e.g. if the participant tells them something which they feel they should tell the police/social services).

- They should be aware of their own values and biases and those of the participants.

Arguments for SSR

- Psychologists have devised methods to resolve the issues raised.

- SSR is the most scrutinized research in psychology. Ethical committees reject more SSR than any other form of research.

- By gaining a better understanding of issues such as gender, race, and sexuality, we are able to gain greater acceptance and reduce prejudice.

- SSR has been of benefit to society, for example, EWT. This has made us aware that EWT can be flawed and should not be used without corroboration. It has also made us aware that the EWT of children is every bit as reliable as that of adults.

- Most research is still on white middle-class Americans (about 90% of research is quoted in texts!). SSR is helping to redress the balance and make us more aware of other cultures and outlooks.

Arguments against SSR

- Flawed research has been used to dictate social policy and put certain groups at a disadvantage.

- Research has been used to discriminate against groups in society, such as the sterilization of people in the USA between 1910 and 1920 because they were of low intelligence, criminal, or suffered from psychological illness.

- The guidelines used by psychologists to control SSR lack power and, as a result, are unable to prevent indefensible research from being carried out.

American Psychological Association. (2002). American Psychological Association ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. www.apa.org/ethics/code2002.html

Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram’s” Behavioral study of obedience.”. American Psychologist , 19 (6), 421.

Caughy, M. O. B., DiPietro, J. A., & Strobino, D. M. (1994). Day‐care participation as a protective factor in the cognitive development of low‐income children. Child development , 65 (2), 457-471.

Harris, B. (1988). Key words: A history of debriefing in social psychology. In J. Morawski (Ed.), The rise of experimentation in American psychology (pp. 188-212). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1984). Applying Hamlet’s question to the ethical conduct of research: A conceptual addendum. American Psychologist, 39(5) , 561.

Sieber, J. E., & Stanley, B. (1988). Ethical and professional dimensions of socially sensitive research. American psychologist , 43 (1), 49.

The British Psychological Society. (2010). Code of Human Research Ethics. www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/code_of_human_research_ethics.pdf

Further Information

- MIT Psychology Ethics Lecture Slides

BPS Documents

- Code of Ethics and Conduct (2018)

- Good Practice Guidelines for the Conduct of Psychological Research within the NHS

- Guidelines for Psychologists Working with Animals

- Guidelines for ethical practice in psychological research online

APA Documents

APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct

Counseling Ethics Code: 10 Common Ethical Issues & Studies

Despite their potentially serious consequences, ethical issues are common, and without preparation and reflection, many might be violated unwittingly and with good intentions.

In this article, you’ll learn how to identify and approach a variety of frequently encountered counseling ethical issues, and how a counseling ethics code can be your moral compass.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Counseling & psychotherapy ethics code explained, 7 interesting case studies, 3 common ethical issues & how to resolve them, ethical considerations for group counseling, a take-home message.

Most of us live by a certain set of values that guide our behavior and mark the difference between right and wrong. These values almost certainly influence how you approach your work as a counselor .

Following these values might feel natural and even intuitive, and it might feel as though they don’t warrant closer examination. However, when practicing counseling or psychotherapy, working without a defined counseling code of ethics is a bit like sailing a ship without using a compass. You might trust your intuitive sense of direction, but more often than not, you’ll end up miles off course.

Fortunately, there are a variety of professional organizations that have published frameworks to help counselors navigate the challenging and disorienting landscape of ethics.

Members of these organizations are often recommended or required to adhere to a framework, so if you belong to one of them and you’re not familiar with their respective code of ethics, this should be your first port of call. However, these ethical frameworks are also often available online for anyone to read, and so you don’t need to join an organization to adhere to its principles.

Each organization takes a slightly different approach to their code of ethics, so you may find it useful to view several to find one that resonates best with your practice. As an example, the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy (2018) has a framework that emphasizes aspiring to a variety of different values and personal moral qualities.

Those values include protecting clients, improving the wellbeing and relationships of others, appreciating the diversity of perspectives, and honoring personal integrity. Personal moral qualities include courage, empathy , humility, and respect.

These values and qualities are not meant to be strict criteria, and there is no wholly objective way to interpret them. For example, two counselors might display the same legitimate values and qualities while arriving at different conclusions to an ethical problem. Instead, they reflect a general approach to how a counselor should think about ethics.

Nevertheless, this approach to ethics may be overly prescriptive for you, in which case a looser and more general framework may be better suited to the nature of your practice. Most professional organizations recognize this, and there is a set of foundational principles that feature widely across different frameworks and refine the collection of different values and qualities described above into simpler terms.

These principles are autonomy , beneficence, non-maleficence, fidelity, justice, veracity, and self-respect (American Counseling Association, 2014; British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy, 2018). They are largely consistent across frameworks aside from some minor variations.

- Autonomy is the respect for a client’s free will.

- Beneficence and non-maleficence are the commitment to improve a client’s wellbeing and avoid harming them, respectively.

- Fidelity is honoring professional commitments.

- Veracity is a commitment to the truth.

- Justice is a professional commitment to fair and egalitarian treatment of clients.

- Self-respect is fostering a sense that the counselor is also entitled to self-care and respect.

Putting these principles into practice doesn’t require a detailed framework. Instead, as the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (2018) recommends, you can simply ask yourself, “ Is this decision supported by these principles without contradiction? ” If so, the decision is ethically sound. If not, there may be a potential ethical issue that warrants closer examination.

Regardless of whether you navigate using values, qualities, or principles, it’s important to be prepared for how they might be challenged in practice. As explained above, these are not intended to be strict criteria, and it’s good to foster a healthy amount of flexibility and intuition when applying your ethical framework to real-life situations.

You might also interpret challenges to other principles. There is no correct or incorrect interpretation to any of these cases (Cottone & Tarvydas, 2016; Zur, 2008).

For each, consider where you think the problem lies and how you would respond.

A counselor has been seeing their client for several months to work through substance use issues. A good rapport has been formed, but the client has not complied with meeting goals set during therapy and has not reduced their substance use.

The counselor feels they may benefit from referring the client to a trusted colleague who specializes in helping individuals with substance use issues who are struggling to engage with therapy. The counselor contacts the colleague and arranges an appointment within their client’s schedule.

When the client is informed, the client is upset and does not wish to be seen by the colleague. The counselor replies that rescheduling is not possible, and they should consider the appointment a necessary part of therapy.

Beneficence

A counselor working as part of a university service is assigned a client expressing issues with their body image. The counselor lacks any knowledge in working with these issues, but feels as though they may help the client, given the extent of their experience with other issues.

On reflection, the counselor decides to contact a colleague outside the university service who specializes in body image issues and asks for supervision and advice.

Non-maleficence

A counselor developing a new exposure-based form of anxiety therapy is working with a client with severe post-traumatic stress. There is promising evidence suggesting the therapy is effective for reducing mild anxiety, but it is unknown whether the therapy is effective in more extreme cases.

As a result, the counselor recognizes that this client in particular would provide a particularly valuable case study for developing the therapy. The counselor recommends this therapy to the client.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

A client with a history of depression and suicidal ideation has been engaging successfully with therapy for the last year. However, recently they have experienced an unfortunate coincidence of extremely challenging life events because of their unstable living arrangement.

The counselor has noticed problematic behaviors and thought patterns emerging, and is seriously concerned about the client’s mental health given the history.

In order to have the client moved from their challenging living environment, they decide to recommend that the client be hospitalized for suicidal ideation, despite there being no actual sign of suicidal ideation and their client previously expressing the desire to avoid hospitalization.

A school counselor sees two students who are experiencing stress regarding their final exams. The first is a high-achieving and popular student who is likable, whereas the second is a student with a history of poor attendance and engagement with their education.

The counselor agrees that counseling is appropriate for the first student, but recommends the second student does not attend counseling, instead addressing the “transient” exam stress by directing their energy into “working harder.”

A counselor is assigned a teenage client after both the client and their family consent to therapy for issues with low mood. After the first session together, it is apparent that the client has been withholding information about their mental health from their family and is showing symptoms typical of clinical depression.

The counselor knows that their client is a high-performing student about to enter a prestigious school and that the client’s family has high hopes for the future. The counselor reassures the family that there is no cause for serious concern in order to protect them from facing the negative implications of the client’s condition.

Self-interest

A counselor is working with a client who is a professional massage therapist. The client offers a free massage therapy session to the counselor as a gesture of gratitude. The client explains that this is a completely platonic and professional gesture.

The counselor has issues with close contact and also feels as though the client’s gesture may not be entirely platonic. The counselor respectfully declines the offer and suggests they continue their relationship as usual. However, the client discontinues therapy abruptly in response.

Ethics in counseling

Ethical issues do not occur randomly in a vacuum, but in particular situations where various factors make them more likely. As a result, although ethical issues can be challenging to navigate, they are not necessarily difficult to anticipate.

Learning to recognize and foresee common ethical issues may help you remain vigilant and not be taken unaware when encountering them.

Informed consent

Issues of consent are common in therapeutic contexts. The right to informed consent – to know all the pertinent information about a decision before it is made – is a foundational element of the relationship between a counselor and their client that allows the client to engage in their therapy with a sense of autonomy and trust.

In many ways, consent is not difficult at all. Ultimately, your client either does or does not consent. But informed consent can be deceptively difficult.

As a brief exercise, consider what “informed” means to you. What is the threshold for being informed? Is there a threshold? Is it more important to be informed about some aspects of a choice than others? These questions do not necessarily have a clearcut answer, but nevertheless it is important to consider them carefully. They may determine whether or not your client has given sufficient consent (West, 2002).

A related but distinct challenge to informed consent is that it is inherently subjective. For example, your client may have as much knowledge about a decision as you do and feel as though they fully understand what a decision entails. However, while you have both experience and knowledge of the decision, they only have knowledge.

That is to say, to some extent, it is not possible for your client to be informed about something they have not actually experienced, as their anticipated experience based on their knowledge may be wholly different from their actual experience.

The best resolution to these issues is to avoid treating informed consent like a checkbox that needs to be satisfied, where the client is required to ingest information and then give their consent.

Instead, encourage your client to appreciate the importance of their consent, reflect on their decision, and consider the limitations of their experience. In doing so, while they may not be able to become fully informed in an objective sense, they will achieve the nearest approximation.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Termination of therapy

Another time of friction when ethical issues can surface is at the conclusion of therapy , when the counselor and client go their separate ways. When this termination is premature or happens without a successful resolution of the client’s goals, it is understandable why this time is difficult.

This can be a challenging transition even when therapy is concluded after a successful result. Like any relationship, the one between a counselor and client can become strained when the time comes for it to end.

Your client may feel uncertain about their ability to continue independently or may feel rejected when reminded of the ultimately professional and transactional nature of the relationship (Etherington & Bridges, 2011).

A basic preemptive action that can be taken to reduce the friction between you and your client during this time is ‘pre-termination counseling,’ in which the topic of termination is explicitly addressed and discussed.

This can be anything from a brief conversation during one of the concluding appointments, to a more formal exploration of termination as a concept. Regardless, this can give your client the opportunity to acclimatize and highlight any challenges related to termination that may be important to explore before the conclusion of therapy.

These challenges may involve features of your client’s background such as their attachment history, which may predispose them toward feelings of abandonment, or their experience of anxiety, which may influence their perceived ability to cope independently after therapy.

If you already have knowledge of these features of your client’s background, it may be worth considering these potential challenges well in advance of the termination of therapy.

Online counseling

Remote forms of therapy are becoming increasingly common. This has many obvious benefits for clients and counselors alike; counseling is more accessible than ever, and counselors can offer their services to a broad and diverse audience. However, online counseling is also fraught with commonly encountered ethical issues (Finn & Barak, 2010).

As remote practice frequently takes place outside the structured contexts more typical of traditional counseling, ethical issues commonly encountered in online counseling are rooted in this relative informality.

Online counseling lacks the type of dedicated ethical frameworks described above, which means e-counselors may have no choice but to operate using their own ethical compass or apply ethical frameworks used in traditional counseling that may be less appropriate for remote practice.

Research suggests that some online counselors may not consider the unique challenges of working online (Finn & Barak, 2010). For example, online counselors may feel as though they do not have the same responsibility for mandatory reporting, as their relationship with their clients may not be as directly involved as in traditional counseling.

For online counselors who are aware of their duty to report safeguarding concerns, the inherent anonymity of online clients may present a barrier. Anonymity certainly has the benefit of improved discretion, but it also means a counselor may be unable to identify their client if they feel they are threatened or otherwise endangered.

Online counselors may also be unclear regarding the limits of their jurisdiction, as qualifications or professional memberships attained in one region may not be applicable in others. It can often seem like borders do not exist online, and while to some extent this is true, it is important to respect that jurisdictions exist for a reason, and it may be unethical to take on a client who you are not licensed to work with.

If you work as an e-counselor, the best way to resolve or preemptively prepare for these issues is to acknowledge they exist and engage with them. A good place to start may be to develop a personal framework for your practice that has a plan for issues of anonymity and confidentiality, and includes an indication of how you will report safeguarding concerns.

In a group setting, clients may no longer feel estranged from society or alone in their challenges, and instead view themselves as part of a community of people with shared experiences.

Clients may benefit from insights generated by other group members, and for some individuals, group counseling may literally amplify the benefits of a one-to-one approach.

However, group settings can also bring unique ethical issues. Just as some groups can bring out the best in us, and a therapeutic context can foster shared insights, other groups can become toxic and create a space in which counter-therapeutic behaviors are enabled by the implicit or explicit encouragement of other group members.

Similarly, just as some group leaders can inspire others and foster a productive community, it is also all too easy for group leaders to become victims of their status.

This is true for any relationship in which there is an inherent imbalance of power, such as traditional one-to-one practice, but in a group context, the counselor is naturally invested with a greater magnitude of influence and responsibility. This can lead to the judgment of the counselor becoming warped and increase the risk of overstepping ethical boundaries (Mashinter, 2020).

As a group counselor, first and foremost, you should foster a diligent practice of self-reflection to ensure you are mindful of the actions you take and remain alert to any blind spots in your judgment.

If possible, it may also be useful to examine ethical issues related to your authority by referring to another authority, in the form of supervision with one of your colleagues.

Finally, to prevent counter-therapeutic dynamics from developing within your group of clients, it may be useful to develop a clear code of conduct that emphasizes a commitment to group beneficence through mutual respect (Marson & McKinney, 2019).

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Take a structured approach to preparing for and dealing with ethical issues, whether this is referring to a framework published by a professional organization or simply navigating by a set of core values.

Prepare for the most common types of ethical issues, while also keeping an open mind to the often complex nature of ethics in practice, as well as the specific ethical issues that may be unique to your practice. Case studies can be a useful tool for doing this.

If in doubt, refer to these five steps from Dhai and McQuiod-Mason (2010):

- Formulate the problem.

- Gather information.

- Consult authoritative sources.

- Consider the alternatives.

- Make an ethical assessment.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- American Counseling Association. (2014). Ethical & professional standards . Retrieved July 22, 2021, from https://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/ethics

- British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. (2018). BACP ethical framework for the counselling professions . Retrieved from https://www.bacp.co.uk/events-and-resources/ethics-and-standards/ethical-framework-for-the-counselling-professions/

- Cottone, R., & Tarvydas, V. (2016). Ethics and decision making in counseling and psychotherapy . Springer.

- Dhai, A., & McQuoid-Mason, D. J. (2010). Bioethics, human rights and health law: Principles and practice . Juta and Company.

- Etherington, K., & Bridges, N. (2011). Narrative case study research: On endings and six session reviews. Counseling and Psychotherapy Research , 11 (1), 11–22.

- Finn, J., & Barak, A. (2010). A descriptive study of e-counselor attitudes, ethics, and practice. Counseling and Psychotherapy Research , 10 (4), 268–277.

- Marson, S. M., & McKinney, R. E. (2019). The Routledge handbook of social work ethics and values . Routledge.

- Mashinter, P. (2020). Is group therapy effective? BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education , 12 (2), 33–36.

- West, W. (2002). Some ethical dilemmas in counseling and counseling research. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling , 30 (3), 261–268.

- Zur, O. (2008). Bartering in psychotherapy & counseling: Complexities, case studies and guidelines. New Therapist , 58 , 18–26.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

I appreciated your insight on the autonomy of the client, and this article was a great help for me in my master’s program and things to consider as I choose the right path for practice.

I enjoyed the lessons

I was recently at a social gathering where a former chemical dependency group counselor also attended. I tried to be polite, however I felt stalked. I was speaking with another person at the event, and he was within earshot of the conversation and hijacked my intent and the conversation. I had to literally seek an escape route. Before the event was over, he knocked my food from my plate and then ran to take the seat intended for me. This person knew that I am a retired professional and had access to my mental and physical health files. To say I was triggered is an understatement. What else could I have done in the moment to protect my psyche from the collateral damage that his inappropriate behaviors caused me? Is there any recourse? Do I now have to avoid the venue for fear he may show up there again and harass me further? Thank you in advance for your prompt attention.

I’m truly sorry to hear about your distressing experience. No one should ever feel cornered or unsafe, especially in social settings. In the moment, prioritizing your safety and well-being is paramount. If you ever find yourself in a similar situation, consider:

– Seeking Support : Approach a trusted friend or event organizer to stay with you, making it less likely for the individual to approach. – Setting Boundaries : Politely yet firmly assert your boundaries if you feel safe to do so. Let the person know their behavior is unwelcome. – Seeking Professional Advice : Consider discussing the situation with a legal professional or counselor to understand potential recourse.

Remember, you have every right to attend venues without fear. If you’re concerned about future encounters, perhaps inform the venue’s management about your experience.

Warm regards, Julia | Community Manager

Thanks for the reminder that group counseling is also a whole different thing compared to a more typical counseling session. I’d like to look for professional counseling services soon because I might need help in processing my grief. After my dog died a month ago, it’s still difficult for me to get on with my life and get on with life normally.

https://www.barbarasabanlcsw.net/therapy-with-me

Thanks the topic is well explained have learnt alot from it

Very informative article. I particularly enjoyed the case studies on the ethical principles

Thanks a lot

Ngini Nairobi, Kenya

very useful article .thank u very much. from… Sri Lanka

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Youth Counseling: 17 Courses & Activities for Helping Teens

From a maturing body and brain to developing life skills and values, the teen years can be challenging, and mental health concerns may arise. Teens [...]

How To Plan Your Counseling Session: 6 Examples

Planning is crucial in a counseling session to ensure that time inside–and outside–therapy sessions is well spent, with the client achieving a successful outcome within [...]

65+ Counseling Methods & Techniques to Apply With Your Clients

Counselors have found it challenging to settle on a single definition of their profession or agree on the best counseling methods and techniques to treat [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

Ethics & Psychology

- General Resources

- Animal Subjects

- Human Subjects

- Case Studies

Collections of Cases

- Ethics Case Studies in Mental Health Research A large collection of cases addressing issues such as human participants in research, conflict of interest, and the responsible collection, management, and use of research data.

- Ethics Education Library -Psychology Case Studies A collection of over 90 case studies from the Ethics Education Library.

- Ethics Rounds A collection of case studies published in the American Psychological Association's "Monitor on Ethics".

Case Investigations by Government Agencies/Professional Organizations

- Office of Research Integrity Cases summaries from the past four years of investigations and inquiries done by the Office of Research Integrity. Also includes short case summaries from 1994 onwards.

Books, Anthologies, & More

- << Previous: Human Subjects

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 10:40 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/psychologyethics

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

APA Code of Ethics: Principles, Purpose, and Guidelines

Codes, Principles, and Standards for Psychologists

Mediaphotos / Getty Images

Understanding the APA Code of Ethics

- APA Code of Ethics' 5 Principles

- The APA Code of Ethics' Standards

- Reporting a Therapist

Ethical Considerations

The big picture.

The APA Code of Ethics equips psychology professionals with standards and principles to follow when dealing with the moral and ethical dilemmas they're likely to face.

Ethics are an important concern in psychology, particularly regarding therapy and research. Working with patients and conducting psychological research can pose various ethical and moral issues that must be addressed.

The American Psychological Association (APA) publishes the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct which outlines aspirational principles as well as enforceable standards that psychologists should use when making decisions.

In 1948, APA president Nicholas Hobbs said, "[The APA Code of Ethics] should be of palpable aid to the ethical psychologist in making daily decisions."

In other words, the APA Code of Ethics is meant to provide a common set of rules that help ensure mutual safety and patient benefit.

When Did the APA Publish Its Code of Ethics?

The APA first published its ethics code in 1953 and has been continuously evolving the code ever since.

What's in the APA's Code of Ethics?

The APA Code of Ethics comprises two key elements:

- Principles : the underlying ethical foundation on which psychologists should base their practices and decisions, whether they work in mental health, research , or business.

- Standards : enforceable rules for ethical conduct, the violation of which can have professional and legal ramifications

Who Is the APA Code of Ethics For?

The APA Code of Ethics applies only to work-related, professional activities including research, teaching, counseling , psychotherapy, and consulting. Private conduct is not subject to scrutiny by the APA's ethics committee.

APA Code of Ethics' 5 Principles

Not all ethical issues are clear-cut, but the APA offers psychologists guiding principles to help them make sound ethical choices within their profession.

The APA Code of Ethics' Five Principles

- Principle A : Beneficence and Non-Maleficence

- Principle B : Fidelity and Responsibility

- Principle C : Integrity

- Principle D : Justice

- Principle E : Respect for People's Rights and Dignity

Principle A: Beneficence and Non-Maleficence

Psychologists should strive to protect the rights and welfare of those with whom they work professionally . This includes the clients they see in clinical practice, animals that are involved in research and experiments , and anyone else with whom they engage in professional interaction.

This principle encourages psychologists to strive to eliminate biases , affiliations, and prejudices that might influence their work. This includes acting independently in research and not allowing affiliations or sponsorships to influence results.

Principle B: Fidelity and Responsibility

Psychologists have a moral responsibility to help ensure that others working in their profession also uphold high ethical standards . This principle suggests that psychologists should participate in activities that enhance the ethical compliance and conduct of their colleagues.

Serving as a mentor, taking part in peer review, and pointing out ethical concerns or misconduct are examples of how this principle might be put into action. Psychologists are also encouraged to donate some of their time to the betterment of the community.

Principle C: Integrity

In research and practice, psychologists should never attempt to deceive or misrepresent . For instance, in research, deception can involve fabricating or manipulating results in some way to achieve desired outcomes. Psychologists should also strive for transparency and honesty in their practice.

Principle D: Justice

Mental health professionals have a responsibility to be fair and impartial. It also states that people have a right to access and benefit from advances that have been made in the field of psychology. It is important for psychologists to treat people equally.

Psychologists should also always practice within their area of expertise and also be aware of their level of competence and limitations.

Principle E: Respect for People's Rights and Dignity

Psychologists should respect the right to dignity, privacy, and confidentiality of those they work with professionally . They should also strive to minimize their own biases as well as be aware of issues related to diversity and the concerns of particular populations.

For example, people may have specific concerns related to their age, socioeconomic status, race , gender, religion, ethnicity, or disability.

The APA Code of Ethics' Standards

The 10 standards found in the APA ethics code are enforceable rules of conduct for psychologists working in clinical practice and academia.

The 10 Standards Found in the APA Code of Ethics

- Resolving Ethical Issues

- Human Relations

- Privacy and Confidentiality

- Advertising and Other Public Statements

- Record Keeping and Fees

- Education and Training

- Research and Publication

These standards tend to be broad in order to help guide the behavior of psychologists across a wide variety of domains and situations.

They apply to areas such as education, therapy, advertising, privacy, research, and publication.

1: Resolving Ethical Issues

This standard of the APA ethics code provides information about what psychologists should do to resolve ethical situations they may encounter in their work. This includes advice for what researchers should do when their work is misrepresented and when to report ethical violations.

2: Competence

Psychologists must practice within their areas of expertise. When treating clients or working with the public, psychologists must make clear what they are and are not trained to do.

An Exception to This Standard

This standard stipulates that in an emergency situation, professionals may provide services even if it falls outside the scope of their practice in order to ensure that access to services is provided.

3: Human Relations

Psychologists frequently work with a team of other mental health professionals. This standard of the ethics code is designed to guide psychologists in their interactions with others in the field.

This includes guidelines for dealing with sexual harassment, and discrimination, avoiding harm during treatment and avoiding exploitative relationships (such as a sexual relationship with a student or subordinate).

4: Privacy and Confidentiality

This standard outlines psychologists’ responsibilities in maintaining patient confidentiality . Psychologists are obligated to take reasonable precautions to keep client information private.

However, the APA also notes that there are limitations to confidentiality. Sometimes psychologists need to disclose information about their patients in order to consult with other mental health professionals, for example.

In cases where information must be divulged, psychologists must strive to minimize these intrusions on privacy and confidentiality.

5: Advertising and Other Public Statements

Psychologists who advertise their services must ensure that they accurately depict their training, experience, and expertise. They also need to avoid marketing statements that are deceptive or false.

This also applies to how psychologists are portrayed by the media when providing their expertise or opinion in articles, blogs, books, or television programs.

When presenting at conferences or giving workshops, psychologists should also ensure that the brochures and other marketing materials for the event accurately depict what the event will cover.

6: Record Keeping and Fees

Maintaining accurate records is an important part of a psychologist’s work, whether the individual is working in research or with patients. Patient records include case notes and other diagnostic assessments used in the course of treatment.

In terms of research, record-keeping involves detailing how studies were performed and the procedures that were used. This allows other researchers to assess the research and ensures that the study can be replicated.

7: Education and Training

This standard focuses on expectations for behavior when psychologists are teaching or training students.

When creating courses and programs to train other psychologists and mental health professionals , current and accurate evidence-based research should be used.

This standard also states that faculty members are not allowed to provide psychotherapy services to their students.

8: Research and Publication

This standard focuses on ethical considerations when conducting research and publishing results .

For example, the APA states that psychologists must obtain approval from the institution that is carrying out the research, present information about the purpose of the study to participants, and inform participants about the potential risks of taking part in the research.

9: Assessment

Psychologists should obtain informed consent before administering assessments. Assessments should be used to support a psychologist’s professional opinion, but psychologists should also understand the limitations of these tools.

They should also take steps to ensure the privacy of those who have taken assessments.

10: Therapy

This standard outlines professional expectations within the context of providing therapy. Areas that are addressed include the importance of obtaining informed consent and explaining the treatment process to clients.

Confidentiality is addressed, as well as some of the limitations to confidentiality, such as when a client poses an immediate danger to himself or others.

Minimizing harm, avoiding sexual relationships with clients, and continuation of care are other areas that are addressed by this standard.

For example, if a psychologist must stop providing services to a client for some reason, they are expected to prepare clients for the change and help locate alternative services.

What Happens When a Therapist Violates the APA Code of Ethics?

After a report of unethical conduct is received, the APA may censure or reprimand the psychologist, or the individual may have their APA membership revoked. Complaints may be referred to others, including state professional licensing boards.

State psychological associations, professional groups, licensing boards, and government agencies may also choose to impose penalties against the psychologist.

Health insurance agencies and state and federal payers of health insurance claims may also pursue action against professionals for ethical violations related to treatment, billing, or fraud.

Those affected by ethical violations may also opt to seek monetary damages in civil courts.

Illegal activity may be prosecuted in criminal courts. If this results in a felony conviction, the APA may take further actions including suspension or expulsion from state psychological associations and the suspension or loss of the psychologist's license to practice.

How Can I Report a Therapist for Unethical Behavior?

Unfortunately, therapists do commit ethical violations. If you would like to file a complaint against a therapist, contact your state's psychologist licensing board.

How to Find Your State's Psychologist Board

Here is a list of the U.S. psychology boards . Choose your state and refer to the contact information provided.

Because psychologists often deal with extremely sensitive or volatile situations, ethical concerns play a big role in professional life.

The most significant ethical issues include:

- Client Welfare : Given the roles they serve, psychologists often work with individuals who are vulnerable due to their age, disability, intellectual ability, and other concerns. When working with these individuals, psychologists must always strive to protect the welfare of their clients.

- Informed Consent : Psychologists are responsible for providing a wide range of services in their roles as therapists, researchers, educators, and consultants. When people are acting as consumers of psychological services, they have a right to know what to expect. In therapy, obtaining informed consent involves explaining what services are offered, what the possible risks might be, and the patient’s right to leave treatment. When conducting research, informed consent involves letting participants know about any possible risks of taking part in the research.

- Confidentiality : Therapy requires providing a safe place for clients to discuss highly personal issues without fear of having this information shared with others or made public. However, sometimes a psychologist might need to share some details such as when consulting with other professionals or when they are publishing research. Ethical guidelines dictate when and how some information might be shared, as well as some of the steps that psychologists should take to protect client privacy.

- Competence : The training, education, and experience of psychologists is also an important ethical concern. Psychologists must possess the skill and knowledge to properly provide the services that clients need. For example, if a psychologist needs to administer a particular assessment in the course of treatment, they should have an understanding of both the administration and interpretation of that specific test.

Although the APA Code of Ethics provides respected principles and enforceable standards for professional conduct, psychology is not free from ethical controversy. For example, debates over psychologists’ participation in torture and the use of animals in psychological research remain hot-button ethical concerns.

Nevertheless, reputable psychologists commonly turn to the APA Code of Ethics for help with moral and ethical issues and decisions commonly faced in their profession.

American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Including 2010 and 2016 Amendments. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association 2020 https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

Hobbs N. The development of a code of ethical standards for psychology . American Psychologist. 1948;3(3):80–84.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0060281

Conlin WE, Boness CL. Ethical considerations for addressing distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56(4):449-458. doi:10.1037/pst0000252

Stark L. The science of ethics: Deception, the resilient self, and the APA code of ethics, 1966-1973. J Hist Behav Sci . 2010;46(4):337-370. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20468

Smith RD, Holmberg J, Cornish JE. Psychotherapy in the #MeToo era: Ethical issues . Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56(4):483-490. doi:10.1037/pst0000262

Erickson Cornish JA, Smith RD, Holmberg JR, Dunn TM, Siderius LL. Psychotherapists in danger: The ethics of responding to client threats, stalking, and harassment. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56(4):441-448. doi:10.1037/pst0000248

American Psychological Association. Complaints regarding APA members .

American Psychological Association. Council Policy Manual. Policy Related to Psychologists' Work in National Security Settings and Reaffirmation of the APA Position Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Adopted by APA Council of Representatives, August 2013. Amended by APA Council of Representatives, August 2015. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association 2020 https://www.apa.org/about/policy/national-security

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychiatr Psychol Law

- v.25(3); 2018

Moral Challenges for Psychologists Working in Psychology and Law

Alfred allan.

School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia

States have an obligation to protect themselves and their citizens from harm, and they use the coercive powers of law to investigate threats, enforce rules and arbitrate disputes, thereby impacting on people's well-being and legal rights and privileges. Psychologists as a collective have a responsibility to use their abilities, knowledge, skill and experience to enhance law's effectiveness, efficiency, and reliability in preventing harm, but their professional behaviour in this collaboration must be moral. They could, however, find their personal values to be inappropriate or there to be insufficient moral guides and could find it difficult to obtain definitive moral guidance from law. The profession's ethical principles do, however, provide well-articulated, generally accepted and profession-appropriate guidance, but practitioners might encounter moral issues that can only be solved by the profession as a whole or society.

Disciplines and professions have an obligation to serve the interests of both society and its individual members (MacDonald, 1995 ; Parsons, 1968 ). Modern societies and individuals therefore expect psychologists to provide services to law that I define broadly to include the correction, investigative and justice systems. Psychologists provide services to these systems directly as administrators, consultants, policy advisers or practitioners using psychological resources (data, methods and instruments) that other psychologists have created as researchers, documented, edited, reviewed or taught. Some practitioners use these resources to provide therapeutic or rehabilitation services, but my focus is on the psychologists (assessors) who use psychological resources to generate information that law uses to make decisions that invariably impact on people's well-being and their legal rights and privileges.

Society's Use of Law and Coercion

The roots of law go back to the hunter-gatherer groups, which could only survive external threats and achieve their goals by ensuring internal order, strengthening the cohesion of the group, promoting mutually beneficial cooperation, and checking destructive selfish behaviour (Cosmides, 2015 ; Krasnow, Delton, Cosmides, & Tooby, 2015 ). Modern neuroscientists and psychologists (see, e.g. Rilling & Sanfey, 2011 ) confirm the belief of generations of scholars that people crave structure and order (see, e.g. Freud, 1927 ; Kelsen, 1943 ; Mill, 1859/ 1974 ) and feel wronged when others violate social norms (Rilling & Sanfey, 2011 ; Sanfey, 2007 ). Researchers (see, e.g. Pietrini, Guazzelli, Basso, Jaffe, & Grafman, 2000 ; Strang, Fischbacher, Utikal, Weber, & Falk, 2014 ) also confirm the historical view (see, e.g. Kelsen, 1943 ; Piaget, 1932/ 1965 ) that people's primitive survival need to protect themselves and significant others from further abuse (Von Fürer-Haimendor, 1967 ) predisposes victims to retaliate by taking revenge (for a discussion see McCullough, Kurzban, & Tabak, 2013 ; Tripp & Bies, 1997 ).

States try to prevent vigilante behaviour (Hogan & Emler, 1981 ) that can lead to harmful cycles of violence by creating law that provides victims access to grievance procedures and remedies that they can use to offset the consequences of wrongful behaviour. Law therefore allows State organs to intervene in disputes by forcing people to undertake activities (e.g. community service, paying damages or fines) or to discontinue activities (e.g. trespassing on property or contacting specific people), or suspending or modifying their rights or privileges (e.g. imprisoning them or restricting their access to, or opportunity to parent, their children).

Since the 16th century, States involuntarily detain people whose lack of insight as a consequence of their mental disorders might cause them to harm themselves or others, on the basis that they lack the competency to make rational decisions (Allan, 2002 ). States, however, also increasingly use the risk of harm to people and the broader society to justify regulating the activities of competent people, such as compelling cyclists to wear head protection, preventing people from smoking in public spaces or paying for consensual sex (Mis, 2016 ). States further use criminal law to investigate and control the behaviour of people, and psychologists have recently expressed moral concerns about their peers’ involvement in three types of regulation of activities.

Law, firstly, uses psychologists to assess people's risk of reoffending in an attempt to control those with a propensity to commit crimes. Law tries to prevent these people from committing future crimes by detaining them (even if they had not been found guilty of crimes, see, e.g. McSherry, 2014 ), or compelling them to wear radio transmitters, or preventing them from going to locations (e.g. close to schools).

Law, secondly, uses psychologists to develop behavioural profiles of suspects using covertly collected information (Allan, 2015 ) or using information for another purpose than that for which they had obtained consent to use it (see, e.g. Inmate Welfare Committee, William Head Institution v Canada, 2003 – Inmate case). The Canadian Federal Court in the Inmate case held that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and Bill of Rights (Charter; Canadian Constitution Act, 1982 ) did not stop Correctional Services Canada (Corrections Canada) psychologists from completing a Psychopathy Checklist–Revised (PCL–R; Hare, 1991 ) using file data without offenders’ consent if Corrections Canada needed it to fulfil its legislative mandate of protecting the public.

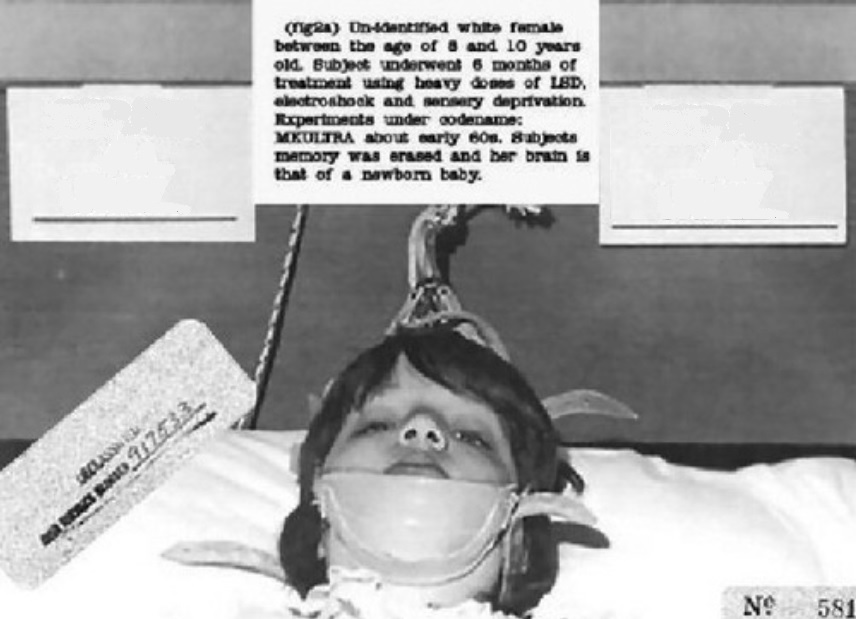

The final concern is psychologists’ involvement in forensic interviews and interrogations as supervisors or consultants of investigators (e.g. observing actual or video recordings of interviews and making suggestions to interviewers) or as investigative interviewers (e.g. in family and child protection or criminal matters). Law has used interviews since the dawn of history (Donohue, 2008 ), but people who associate them with the Inquisition (Burman, 2004 ) and police abuse (Ofshe & Leo, 1997 ) often view them negatively. Psychology's involvement with interviews is not new because interviewers, interrogators and investigators have used psychological data (Münsterberg, 1908/1925) , and psychologists have adopted investigative roles (see, e.g. Marbe, 1930 ; Münsterberg, 1908/ 1925 ) since the emergence of psychology as a separate discipline. Psychologists’ purported involvement in so-called enhanced interviewing and its association with torture, however, has led to contemporary debates about psychologists’ role and the use of psychological knowledge during interviews and interrogations (see, e.g. Arrigo, DeBatto, Rockwood, & Mawe, 2015 ; O'Donohue, Maragakis, Snipes, & Soto, 2015 ; O'Donohue et al., 2014 ; Suedfeld, 2007 ).

A theme underlying these three activities is that they involve psychologists in law's use of ‘organized coercion ‘ (Lloyd, 1964 , p. 41) to achieve its goals (Dworkin, 1986 ; Hart, 2012 ). Philosophers accept that States can use coercive legal powers to control autonomous people's behaviour, but since the 18th (Von Humboldt, 1792/1854) and 19th (Mill, 1859/1974) centuries they argued that this is only justified when directed toward prevention of harm to other individuals (the private harm principle ). Modern philosophers argue that there is also a public harm principle that allows States to use coercion to prevent harm to public interests (see, e.g. Feinberg, 1973 ). States that use coercion to prevent harm, however, often also cause unavoidable and unintended harm (see, e.g. Gatti, Tremblay, & Vitaro, 2009 ), and therefore the net result might be immoral (wrong and/or bad). Citizens should therefore scrutinise the morality (rightness and goodness) of the purpose, provisions and administration of coercive legislation.

Some argue that legislators sometimes introduce coercive criminal legislation for the purpose of attracting votes rather than preventing harm (see, e.g. Nutall, 2000 ), whilst others contend that it reflects the public's punitive and intolerant opinion about certain forms of offending behaviour (see, e.g. De Keijser, 2014 ; De Keijser & Elffers, 2009 ), such as terrorism (Carlé, Charron, Milochevitch, & Hardeman, 2004 ; Van de Lagemaat, 2012 ). Perceived public opinion, however, might not accurately reflect public morality (i.e. what society as a whole considers as right and good) because it fluctuates depending on variables such as people's education and socio-economic status (Carpenter, 1889 ) and could be swayed by external influences such as biased messages from police in search of more resources and the media that make money out of crime coverage (Roberts & Plesničar, 2015 ). People should further consider the provisions of the relevant legislation that determine the kind, magnitude, probability and immediacy of the targeted harm that justify the unavoidable and unintended harm caused by the lawful intervention (Brookbanks, 2002 ). In particular, they need to consider who should determine the relevant risks and what degree of certainty they should have that interventions will cause direct and immediate harm of a lesser magnitude than the targeted harm (McAlinden, 2001 ). Psychologists might not necessarily engage in the debate regarding the purpose and provisions of relevant legislation, but they should consider the moral appropriateness of their direct or indirect involvement in the administration of the relevant legislation.

Personal Decision Making