'Ulysses' Review

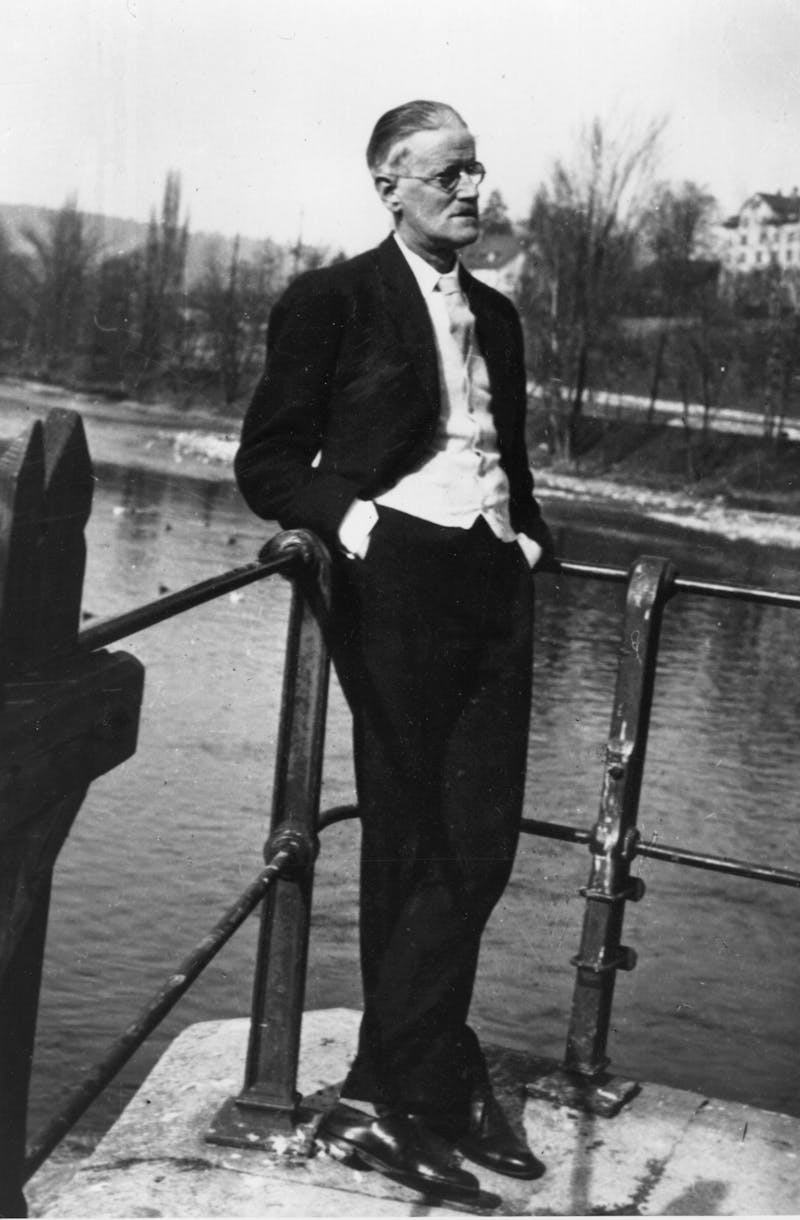

Paul Hermans / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

- Best Seller Reviews

- Best Selling Authors

- Book Clubs & Classes

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

Ulysses by James Joyce holds a very special place in the history of English literature. The novel is one of the greatest masterpieces of modernist literature . But, Ulysses is also sometimes seen as so experimental that it is completely unreadable.

Ulysses records events in the lives of two central characters--Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus--on a single day in Dublin. With its depth and complexities, Ulysses completely changed our understanding of literature and language.

Ulysses is endlessly inventive, and labyrinthine in its construction. The novel is both a mythical adventure of the every day and a stunning portrait of internal psychological processes--rendered through high art. Brilliant and sparkling, the novel is difficult to read but offers rewards tenfold the effort and attention that willing readers give it.

The novel is as difficult to summarize as it is difficult to read, but it has a remarkably simple story. Ulysses follows one day in Dublin in 1904--tracing the paths of two characters: a middle-aged Jewish man by the name of Leopold Bloom and a young intellectual, Stephen Daedalus. Bloom goes through his day with the full awareness that his wife, Molly, is probably receiving her lover at their home (as part of an ongoing affair). He buys some liver, attends a funeral and, watches a young girl on a beach.

Daedalus passes from a newspaper office, expounds a theory of Shakespeare's Hamlet in a public library and visits a maternity ward--where his journey becomes intertwined with Bloom's, as he invites Bloom to go along with some of his companions on a drunken spree. They end up at a notorious brothel, where Daedalus suddenly becomes angry because he believes the ghost of his mother is visiting him.

He uses his cane to knock out a light and gets into a fight--only to be knocked out himself. Bloom revives him and takes him back to his house, where they sit and talk, drinking coffee into the wee hours. In the final chapter, Bloom slips back into bed with his wife, Molly. We get a final monologue from her point of view. The string of words is famous, as it is entirely devoid of any punctuation. The words just flow as one long, full thought.

Telling the Story

Of course, the summary doesn't tell you a whole lot about what the book is really all about. The greatest strength of Ulysses is the manner in which it is told. Joyce's startling stream-of-consciousness offers a unique perspective on the events of the day; we see the occurrences from the interior perspective of Bloom, Daedalus, and Molly. But Joyce also expands upon the concept of stream of consciousness .

His work is an experiment, where he widely and wildly plays with narrative techniques. Some chapters concentrate on a phonic representation of its events; some are mock-historical; one chapter is told in epigrammatic form; another is laid out like a drama. In these flights of style, Joyce directs the story from numerous linguistic as well as psychological points of view. With his revolutionary style, Joyce shakes the foundations of literary realism. After all, aren't there a multiplicity of ways to tell a story? Which way is the right way? Can we fix on any one truthful way to approach the world?

The Structure

The literary experimentation is also wedded to a formal structure that is consciously linked to the mythical journey recounted in Homer's Odyssey ( Ulysses is the Roman name of that poem's central character). The journey of the day is given a mythical resonance, as Joyce mapped the events of the novel to episodes that occur in the Odyssey .

Ulysses is often published with a table of parallels between the novel and the classical poem; and, the scheme also offers insight into Joyce's experimental use of the literary form, as well as some understanding of how much planning and concentration went into the construction of Ulysses.

Intoxicating, powerful, often incredibly disconcerting, Ulysses is probably the zenith of modernism's experimentation with what can be created through language. Ulysses is a tour de force by a truly great writer and a challenge for completeness in the understanding of language that few could match. The novel is Brilliant and taxing. But, Ulysses very much deserves its place in the pantheon of truly great works of art.

- 'The Da Vinci Code' by Dan Brown: Book Review

- Review of "For One More Day" by Mitch Albom

- Book Review of "The Reader" by Bernhard Schlink

- 'The Secret Life of Bees' by Sue Monk Kidd: Book Review

- Everything You Need to Know about the Stone Barrington Books

- Angels and Demons Book Review

- How to Read George Saunders' “Lincoln in the Bardo”

- Jodi Picoult - Most Recent Releases

- The Choice by Nicholas Sparks Book Review

- 'The Kite Runner' by Khaled Hosseini - Book Review

- 'Dear John' by Nicholas Sparks Book Review

- "The Heidi Chornicles" by Wendy Wasserstein

- Why You Must Read the Book 'Hidden Figures'

- A Critical Review of 'Death of a Salesman'

- 'Copenhagen' by Michael Frayn Is Both Fact and Fiction

- "Topdog/Underdog" Play Summary

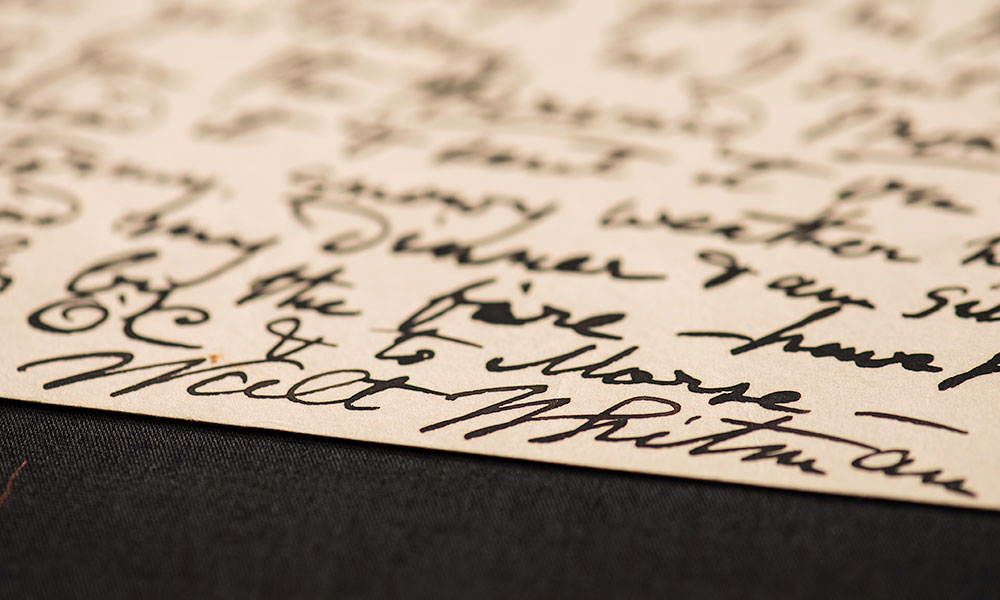

The New Republic's review of James Joyce’s Ulysses

On the 16th of June, 1904, Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom were both living in Dublin. Both differed from the people about them and walked in isolation among them because each was, according to his capacity, an intellectual adventurer—Dedalus, the poet and philosopher, with a mind full of beautiful images and abstruse speculations and Bloom, the advertisement canvasser, in a more rudimentary fashion. In the evening, Mr. Bloom and Dedalus became involved in the same drunken party and Dedalus was knocked unconscious in a quarrel with a British soldier. Then their kinship was made plain. Bloom felt wistfully that Stephen was all he would have had his own son be and Stephen, who despised his own father—an amiable wastrel—found a sort of spiritual father in this sympathetic Jew, who, mediocre as he was, had at least the dignity of intelligence. Were they not both outlaws to their environment by reason of the fact that they thought and imagined ?

Stated in the baldest possible terms, this is the story of Ulysses —an ironic and amusing anecdote without philosophic moral. In describing the novel thus, I have the authority of the author himself, who said to Miss Djuna Barnes, in an interview published in Vanity Fair : “The pity is the public will demand and find a moral in my book—or worse they may take it in some more serious way, and on the honor of a gentleman, there is not one single serious line in it.” The thing that makes Ulysses imposing is, in fact, not the theme but the scale upon which it is developed. It has taken Mr. Joyce seven years to write Ulysses and he has done it in seven hundred and thirty pages which are probably the most completely “written” pages to be seen in any novel since Flaubert. Not only is the anecdote expanded to its fullest possible bulk—there is an elaborate account of nearly everything done or thought by Mr. Bloom from morning to night of the day in question—but you have both the “psychological” method and the Flaubertian method of making the style suit the thing described carried several steps further than they have ever been before, so that, whereas in Flaubert you have merely the words and cadences carefully adapted to convey the specific mood or character without any attempt to identify the narrative with the stream of consciousness of the person described, and in Henry James merely the exploration of the stream of consciousness with only one vocabulary and cadence for the whole cast of moods and characters, in Joyce you have not only life from the outside described with Flaubertian virtuosity but also the consciousness of each of the characters and of each of the character’s moods made to speak in the idiom proper to it, the language it uses to itself. If Flaubert taught de Maupassant to find the adjective which would distinguish a given hackney-cab from every other hackney-cab in the world, James Joyce has prescribed that one must find the dialect which would distinguish the thoughts of a given Dubliner from those of every other Dubliner. So we have the thoughts of Mr. Bloom presented in a rapid staccato notation continually jetting out in all directions in little ideas within ideas with the flexibility and complexity of an alert and nimble mind; Mrs. Bloom’s in a long rhythmic brogue like the swell of some profound sea; Father Conmee’s in precise prose, perfectly colorless and orderly; Stephen Dedalus’s in a kaleidoscope of bright images and fragments of things remembered from books; and Gerty-Nausicaa’s half in school girl colloquialisms and half in the language of the cheap romances which have given their color to her mind. And these voices are used to record all the eddies and stagnancies of thought; though exercising a severe selection which makes the book a technical triumph, Mr. Joyce manages to give the effect of unedited human minds, drifting aimlessly along from one triviality to another, confused and diverted by memory, by sensation and by inhibition. It is, in short, perhaps the most faithful X-ray ever taken of the ordinary human consciousness.

And as a result of this enormous scale and this microscopic fidelity the chief characters in Ulysses take on heroic proportions. Each one is a room, a house, a city in which the reader can move around. The inside of each one of them is a novel in itself. You stand within a world infinitely populated with the swarming life of experience. Stephen Dedalus, in his scornful pride, rears his brow as a sort of Lucifer; poor Bloom, with his generous impulses and his attempts to understand and master life, is the epic symbol of reasoning man, humiliated and ridiculous, yet extricating himself by cunning from the spirits which seek to destroy him; and Mrs. Bloom, with her terrific force of mingled amorous and maternal affection, with her roots in the dirt of the earth and her joyous flowering in beauty, is the gigantic image of the earth itself from which both Dedalus and Bloom have sprung and which sounds a deep foundation to the whole drama like the ground-tone at the beginning of The Rhine-Gold. I cannot agree with Mr. Arnold Bennett that James Joyce “has a colossal ‘down’ on humanity.” I feel that Mr. Bennett has really been shocked because Mr. Joyce has told the whole truth. Fundamentally Ulysses is not at all like Bouvard et Pécuchet (as some people have tried to pretend). Flaubert says in effect that he will prove to you that humanity is mean by enumerating all the ignobilities of which it has ever been capable. But Joyce, including all the ignobilities, makes his bourgeois figures command our sympathy and respect by letting us see in them the throes of the human mind straining always to perpetuate and perfect itself and of the body always laboring and throbbing to throw up some beauty from its darkness.

Nonetheless, there are some valid criticisms to be brought against Ulysses . It seems to me great rather for the things that are in it than for its success as a whole. It is almost as if in distending the story to ten times its natural size he had finally managed to burst it and leave it partially deflated. There must be something wrong with a design which involves so much that is dull—and I doubt whether anyone will defend parts of Ulysses against the charge of extreme dullness. In the first place, it is evidently not enough to have invented three tremendous characters (with any quantity of lesser ones); in order to produce an effective book they must be made to do something interesting. Now in precisely what is the interest of Ulysses supposed to consist? In the spiritual relationship between Dedalus and Bloom? But too little is done with this. When it is finally realized there is one poignant moment, then a vast tract of anticlimax. This single situation in itself could hardly justify the previous presentation of everything else that has happened to Bloom before on the same day. No, the major theme of the book is to he found in its parallel with the Odyssey : Bloom is a sort of modern Ulysses—with Dedalus as Telemachus—and the scheme and proportions of the novel must be made to correspond to those of the epic. It is these and not the inherent necessities of the subject which have dictated the size and shape of Ulysses. You have, for example, the events of Mr. Bloom’s day narrated at such unconscionable length and the account of Stephen’s synchronous adventures confined almost entirely to the first three chapters because it is only the early books of the Odyssey which are concerned with Telemachus and thereafter the first half of the poem is devoted to the wanderings of Ulysses. You must have a Cyclops, a Nausicaa, an Aeolus, a Nestor and some Sirens and your justification for a full-length Penelope is the fact that there is one in the Odyssey . There is, of course, a point in this, because the adventures of Ulysses were fairly typical; they do represent the ordinary man in nearly every common relation. Yet I cannot but feel that Mr. Joyce made a mistake to have the whole plan of his story depend on the structure of the Odyssey rather than on the natural demands of the situation. I feel that though his taste for symbolism is closely allied with his extraordinary poetic faculty for investing particular incidents with universal significance, nevertheless—because it is the homeless symbolism of a Catholic who has renounced the faith—it sometimes overruns the bounds of art into an arid ingenuity which would make a mystic correspondence do duty for an artistic reason. The result is that one sometimes feels as if the brilliant succession of episodes were taking place on the periphery of a wheel which has no hub. The monologue of Mrs. Bloom, for example, tremendous as it is and though in Mrs. Bloom’s mental rejection of Blazes Boylan in favor of Stephen Dedalus it contains the greatest moral climax of the story, seems to me to lose dramatic force by hanging loose at the end of the book. What we have is nothing less than the spectacle of the earth tending naturally to give birth to higher forms of life, the supreme vindication of Bloom and Dedalus against the brutality and ignorance which surround them, but after the sterilities and practical jokes of the chapters immediately preceding and the general diversion of interest which the Odyssean structure has involved the episode lacks the definite force which a closer integration would have provided for.

These sterilities and practical jokes form my second theme of complaint. Not content with inventing new idioms to reproduce the minds of his characters, Mr. Joyce has hit upon the idea of pressing literary parody into service to create certain kinds of impressions. It is not so bad when in order to convey the atmosphere of a newspaper office he merely breaks up his chapter with newspaper heads, but when he insists upon describing a drinking party in an interminable series of imitations which progresses through English prose from the style of the Anglo-Saxon chronicles to that of Carlyle one begins to feel uncomfortable. What is wrong is that Mr. Joyce has attempted an impossible genre. You cannot be a realistic novelist in Mr. Joyce’s particular vein and write burlesques at the same time. Max Beerbohm’s Christmas Garland is successful because Mr. Beerbohm is telling the other man’s story in the other man’s words but Joyce’s parodies are labored and irritating because he is trying to tell his own story in the other man’s words. We are not interested in his skill at imitation but in finding out what happens to his characters and the parody interposes a heavy curtain between ourselves and them. Even if it were at all conceivable that this sort of thing could be done successfully, Mr. Joyce would be the last man to do it. He has been praised for being Rabelaisian but he is at the other end of the world from Rabelais. In the first place, he has not the style for it—he can never be reckless enough with words. His style is thin—by which I do not mean that it is not strong but that it is like a thin metallic pipe through which the narrative is run—a pipe of which every joint has been fitted by a master plumber. You cannot inflate such a style or splash it about. Mr. Joyce’s native temperament and the method which it has naturally chosen have no room for superabundance or extravagant fancy. It is the method of Flaubert—and of Turgenev and de Maupassant: you set down with the most careful accuracy and the most scrupulous economy of detail exactly what happened to your characters, and merely from the way in which the thing is told—not from any comment of the narrator—the reader draws his ironic inference. In this genre—which has probably brought novel-writing to its highest dignity as an art—Mr. Joyce has long proved himself a master. And in Ulysses most of his finest scenes adhere strictly to this formula. Nothing, for example, could be better in this kind than the way in which the reader is made to find out, without any overt statement of the fact, that Bloom is different from his neighbors, or the scene in which we are made to feel that this difference has become a profound antagonism before it culminates in the open outburst against Bloom of the Cyclops—Sinn Feiner. The trouble is that this last episode is continually being held up by long parodies which break in upon the text like a kind of mocking commentary. It is as if Boule de Suif were padded out with sections from J. C. Squire—or rather from a parodist whose parodies are even more boring than Mr. Squire’s. No: surely Mr. Joyce has done ill in attempting to graft burlesque upon realism; he has written some of the most unreadable chapters in the whole history of fiction.—(If it be urged that Joyce’s gift for fantasy is attested by the superb drunken scene, I reply that this scene is successful, not because it is reckless nonsense but because it is an accurate record of drunken states of mind. The visions that bemuse Bloom and Dedalus are not like the visions of Alice in Wonderland but merely the repressed fears and desires of these two specific consciousnesses externalized and made visible. What the reader sees is not a new fantastic world with new and more wonderful beings but two perfectly recognizable drunken men in a squalid and dingy brothel no harsh detail of which is allowed to escape by the great realist who describes it.)

Yet, for all its appalling longueurs, Ulysses is a work of high genius. Its importance seems to me to lie, not so much in its opening new doors to knowledge—unless in setting an example to Anglo-Saxon writers of putting down everything without compunction—or in inventing new literary forms—Joyce’s formula is really, as I have indicated, nearly seventy-five years old—as in its once more setting the standard of the novel so high that it need not be ashamed to take its place beside poetry and drama. Ulysses has the effect at once of making everything else look brassy. Since I have read it, the texture of other novelists seems intolerably loose and careless; when I come suddenly unawares upon a page that I have written myself I quake like a guilty thing surprised. The only question now is whether Joyce will ever write a tragic masterpiece to set beside this comic one. There is a rumor that he will write no more—that he claims to have nothing left to say—and it is true that there is a paleness about parts of his work which suggests a rather limited emotional experience. His imagination is all intensive; he has but little vitality to give away. His minor characters, though carefully differentiated, are sometimes too drily differentiated, insufficiently animated with life, and he sometimes gives the impression of eking out his picture with the data of a too laborious note-taking. At his worst he recalls Flaubert at his worst—in L’Education Sentimentale . But if he repeats Flaubert’s vices—as not a few have done—he also repeats his triumphs—which almost nobody has done. Who else has had the supreme devotion and accomplished the definitive beauty? If he has really laid down his pen never to take it up again he must know that the hand which laid it down upon the great affirmative of Mrs. Bloom, though it never write another word, is already the hand of a master.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

by James Joyce ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 16, 1975

In 1984 was published the news-capturing scholarly work, the "Critical and Synoptic Edition" of James Joyce's Ulysses, which, as The New York Times said, corrected "almost 5,000 omissions, transpositions and other errors included in previous editions of the seminal 20th-century novel." That remarkable work of scholarship, labor, and love, however, ran to three volumes in heft and rang up at $200 in price. Here, then, comes the single-volume trade-book edition of the same edited and restored text, placing the great novel, in as close to its originally-intended form as can be achieved, within reach of the common reader. Missing only is the vast scholarly apparatus of the longer version, though this one comes with a pleasantly helpful preface by Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann and a methodologically explanatory afterward by Hans Walter Gabler. A welcome event. Publication date, readers will note, is Bloomsday.

Pub Date: June 16, 1975

ISBN: 1613821174

Page Count: -

Publisher: Random House

Review Posted Online: Nov. 2, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: May 15, 1986

GENERAL NONFICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by James Joyce

BOOK REVIEW

by James Joyce illustrated by Viktoria Töttös & developed by Crocobee

edited by Anthony Burgess & by James Joyce

by James Joyce

by E.T.A. Hoffmann ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 28, 1996

This is not the Nutcracker sweet, as passed on by Tchaikovsky and Marius Petipa. No, this is the original Hoffmann tale of 1816, in which the froth of Christmas revelry occasionally parts to let the dark underside of childhood fantasies and fears peek through. The boundaries between dream and reality fade, just as Godfather Drosselmeier, the Nutcracker's creator, is seen as alternately sinister and jolly. And Italian artist Roberto Innocenti gives an errily realistic air to Marie's dreams, in richly detailed illustrations touched by a mysterious light. A beautiful version of this classic tale, which will captivate adults and children alike. (Nutcracker; $35.00; Oct. 28, 1996; 136 pp.; 0-15-100227-4)

Pub Date: Oct. 28, 1996

ISBN: 0-15-100227-4

Page Count: 136

Publisher: Harcourt

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 1996

More by E.T.A. Hoffmann

by E.T.A. Hoffmann ; adapted by Natalie Andrewson ; illustrated by Natalie Andrewson

by E.T.A. Hoffmann & illustrated by Julie Paschkis

TO THE ONE I LOVE THE BEST

Episodes from the life of lady mendl (elsie de wolfe).

by Ludwig Bemelmans ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 23, 1955

An extravaganza in Bemelmans' inimitable vein, but written almost dead pan, with sly, amusing, sometimes biting undertones, breaking through. For Bemelmans was "the man who came to cocktails". And his hostess was Lady Mendl (Elsie de Wolfe), arbiter of American decorating taste over a generation. Lady Mendl was an incredible person,- self-made in proper American tradition on the one hand, for she had been haunted by the poverty of her childhood, and the years of struggle up from its ugliness,- until she became synonymous with the exotic, exquisite, worshipper at beauty's whrine. Bemelmans draws a portrait in extremes, through apt descriptions, through hilarious anecdote, through surprisingly sympathetic and understanding bits of appreciation. The scene shifts from Hollywood to the home she loved the best in Versailles. One meets in passing a vast roster of famous figures of the international and artistic set. And always one feels Bemelmans, slightly offstage, observing, recording, commenting, illustrated.

Pub Date: Feb. 23, 1955

ISBN: 0670717797

Publisher: Viking

Review Posted Online: Oct. 25, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 1955

More by Ludwig Bemelmans

developed by Ludwig Bemelmans ; illustrated by Steven Salerno

by Ludwig Bemelmans ; illustrated by Steven Salerno

by Ludwig Bemelmans

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Rereading 'Ulysses' by James Joyce: The Best Novel Since 1900

The season of lists is now upon us: best book, best film, best album ... of 2010.

But, I was recently tempted by another, older list: the Modern Library's best novels in English since 1900 (first published in 1998 and judged by the likes of Daniel Boorstin, A.S. Byatt, Vartan Gregorian, and William Styron).

Ranked number one is James Joyce's Ulysses , written from 1914 to 21, published in 1922 and a source of controversy every since (for example, banned as obscene in the U.S. until 1933).

My last reading of the novel was in 1962 as an 18-year-old college freshman in one of the best courses I have ever had—a "close reading" introductory humanities class that in the spring semester focused on just four books ( Paradise Lost , Huckleberry Finn , Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man , and Ulysses ). We spent more than a month on Ulysses itself. I first found it dense, perplexing, and often incomprehensible, but after reading and re-reading, after studying interpretations by others, I came to love it (and understand some of it).

Yet as the years passed, and the inevitable dinner conversations occurred about the five best novels we had read, Ulysses was never mentioned by anyone (except the stray English major). And when I would ask about it, most would answer: "have started it several times, but never got very far. Too hard."

So, inspired by the "best novels since 1900 list" , with affection dimmed by time and having forgotten almost everything I may have once known about the novel, I decided to try again almost 50 years later (!!!!).

What I found was two novels: a deeply humanistic one which brilliantly and beautifully captures the life of a day in Dublin primarily through three main characters; and a second, highly literary one of surpassing complexity and, without careful study, limited accessibility.

The deeply humanistic novel gives us remarkable insight into Stephen Dedalus (a young writer who aspires to literary greatness, is haunted by the death of his mother, rejects the superficiality of journalism and is teetering on the edge of alcoholism and dissipation); into Leopold Bloom (an advertising salesman, lapsed Jew, lover of food and drink, son of a suicide, father of a dead son and a ripening teenage daughter and wanderer who traverses Dublin during the day and night, befriends Stephen, and returns to his marital bed which, as he knows well, was the scene of an afternoon affair between one Blazes Boylan and his wife); and into Bloom's wife Molly (a singer and earthy mother/wife who fears aging, is jealous of her younger daughter, longs for a sexual relationship with Bloom, relishes her afternoon affair, talks frankly about her bodily functions, speaks in vivid contradictions about love, children, life, aging and women, and at the end remembers romantically the time when she and Bloom first made love).

Unlike many 19th century novels, this humanistic one does not end in either marriage or death, but in ambiguity about what will happen in the future to Stephen, Bloom and Molly and to their relationships. But this uncertainty grows out of a vivid recreation of the multiple sights, sounds, smells and voices of Dublin on June day in 1904. Bloom's pork kidney breakfast frying in a pan. The sound of the trolley cars. The vomit in the bedside bowl of Stephen's dying mother. Tugs moving across the horizon on the "snotgreen sea." The funeral of an old drunkard. The birth of a child. The arguments in a pub. Bloom masturbating on the beach as he watches a young woman show off her knickers. Stephen and Bloom in the nightmare of Nighttown. Stephen and Bloom at Bloom's home watching the wandering stars and peeing below Molly's window. Molly relieved that her menstruation shows she is not pregnant by Boylan.

Joyce set out to create life in all its fullness without heroic scenes or gestures or declamations but through a fully realized expression of a city and its people on one typical day—and through ironic puncturing of human pomposity and pretense. Despite its reputation as a difficult read, many of the chapters or important passages in Ulysses are accessible to a regular reader who is not a candidate for a PhD. For example: the opening chapter where Stephen is mocked by his friend and critic "stately plump Buck Mulligan; the passages in the pub where Bloom engages in verbal warfare with the anti-Semitic "citizen;" the distant seduction of Bloom on the beach by Gerty McDowell who reveals herself as she leans back to watch the fire works shoot into the sky and then reveals that she is lame as she limps away; and even the last two chapters, one in the form of a catechism revealing the relationship between Stephen and Bloom and the second the famous stream-of-consciousness thoughts of Molly as she lies next to Bloom in the early hours of the morning.

Yet, the second Ulysses , the highly literary one, is still complex and inaccessible to a one-time generalist reader. Like many great works of literature, it requires repeated reading and deep study fully to understand—and ultimately to enjoy—the many dimensions and layers. The most obvious complexity, of course, is the analogy to Homer's Odyssey (Latinized from Greek as Ulysses). The novel is loosely structured to mimic Homer's epic. And the main characters in Joyce's novel have referents in the Odyssey, although with profound differences: Bloom as a non-heroic Ulysses, Stephen as Ulysses' son Telemachus, but son without a strong attachment to his own father; and the faithless Molly as the faithful Penelope. Understanding the ways in which Ulysses is an ironic commentary on the Odyssey, and the ways in which Bloom, Stephen and Molly are, and are not, like Ulysses, Telemachus, and Penelope is a huge enterprise unto itself, upon which books have, of course, been written.

Joyce's novel is also stuffed with allusions and parodies and riddles, many of which require substantial knowledge outside the book. As Joyce himself said, he had "put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep professors busy for centuries arguing over what I mean" which would earn the novel "immortality." One whole chapter on child labor and child birth is written in many different styles of English to show the birth of the language. The novel in various places and various ways addresses complex themes like the relationship between Christians and Jews, the aspirations, failures and pedantry of Irish Nationalism and the Irish Literary Revival, the interconnection between love and betrayal. And the style of the novel is, in fact, many different styles: in abandoning the omniscient narrator, the novel is often read as the true beginning of modernist literature.

So, Joyce's Ulysses is still a very hard read. How hard may be seen by contrasting it with the second "best" novel on the Modern Library list: The Great Gatsby . This novel is surely on everyone's list of top five favorite novels: it is short (one-quarter the length of Ulysses ); it is accessible; it has an engaging narrator; it tells a powerful story from start to finish; it is written in beautiful, lyrical and penetrating prose; and, although it has many complex sub-texts, it sounds a single powerful theme—the failure of a materialistic American dream. Gatsby , too, bears reading and rereading to uncover the layers of complexity, but a first reading—or a reading after long absence—is a powerful, moving narrative experience in a way far different than Ulysses .

Still, I urge that people read the first Ulysses I rediscovered, the deeply humanistic novel which is bursting with the enormous variety of life. I do have to say that my re-introduction to the novel was aided by 24 recorded lectures—simply entitled "Joyce's Ulysses"—delivered by James A.W. Heffernan, emeritus professor of English at Dartmouth (and available from The Teaching Company ). Heffernan focuses primarily on the character and psychology of Stephen, Bloom and Molly but the lectures provide a guide through the chapters of the book and relate them to the Homeric myth and put them in context of other recurrent themes (e.g. Irish Nationalism). Perhaps that reading of the "first" Ulysses will provide a stimulus to explore the almost infinite dimensions of the second, literary one.

Both Gatsby and Ulysses have famous endings.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther...And one fine morning— So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

...and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

Both endings are not without deep ironies. But, the final sentences of Gatsby are about the futility of our dreams. The end of Ulysses is about the affirmation of our humanity.

About the Author

More Stories

The Fatal Flaws of Fatal Attraction

General Sisi's Greatest Enemy: The Egyptian Economy

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

The Best Fiction Books » Classic English Literature

By james joyce.

Ulysses by James Joyce is one of the masterpieces of modernist literature, a movement at the beginning of the 20th century when the traditional storylines of the Victorian novel were left behind to experiment with new ways of expressing human experience. Though hard to read, those who have made the effort are often enthralled by it and regard it as among the very best books they’ve ever read. For that reason alone, Ulysses is worth pursuing, possibly with the help of a guide:

How to Read Ulysses by James Joyce

We asked Patrick Hastings, author of The Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses and a long-term teacher of Ulysses, for some tips about how to read Joyce’s modernist masterpiece.

Why have you dedicated yourself to this book? Is it really something special?

I’ve yet to encounter another work of art that so successfully and thoroughly represents the human condition in the modern era. Ulysses is emotionally moving, intellectually invigorating, and super funny. I never fail to discover something new every time I read a page in the text. It is humbling and exciting in that way.

There are quite a few guides to Ulysses out there, did you feel they needed replacing?

There are lots of great resources out there, and every reader will find the one that best fits the type of reading experience that they are pursuing. In The Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses, I sought to satisfy the reader’s desire for some clarity on what is actually happening in the plot in balance with succinct explanation of the innovative stylistic and allusive techniques. In this way, I hope for my readers to enjoy the story of the novel while also gaining an appreciation for the literary elements that make Ulysses such a masterpiece. I guess I felt that the time was right for a fresh voice to present the novel to a new generation of readers, and I wanted to package together for my readers lots of the scholarship that I’ve found really helpful to my own understanding of the book. Read more

Recommendations from our site

“It’s challenging, learned, filthy, and hilarious. In it, Joyce pushes the boundaries of language and the novel form. It’s easy to see how it was thwarted and censored four times during publication. At first, no one wanted to print it, because they could’ve been found liable for publishing pornography. Ulysses is one of those great novels that demands a level of concentration one can only get in isolation. Yes, it’s difficult and frustrating, but that’s because it wants to frustrate you—and the payoff is immense pleasure: no book gets closer to the ineffable experience of human play and tragedy, of being a fleshy mass of blood and bones in the modern world” Read more...

The Best Long Books To Read in Lockdown

“This novel is still—after nearly a century—powerful, innovative and exhilarating. There is more going on in one sentence in Ulysses than there is in most contemporary novels.” Read more...

Robin Robertson on Books that Influenced Him

Robin Robertson , Novelist

“It is seen as the archetypal stream of consciousness novel. With more ambition than possibly any other writer, Joyce tries to get us into the inner monologues and dialogues of Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom, and Stephen Dedalus. He didn’t invent the technique. but he makes it flourish in the most extraordinary way.” Read more...

The best books on Streams of Consciousness

Charles Fernyhough , Novelist

“It’s a novel published after about 1910. It’s a novel that takes the traditional elements of place and time and mashes them up and reorders them. It attempts to capture the flow of human thought and human experience on the page in words and has no apparent interest in the conventions of the Victorian novel. It’s trying to represent the ordinary world in prose. Ulysses is a very brilliant, highly original attempt to put one man’s experience on one day to the pages of a book.” Read more...

The Best Novels in English

Robert McCrum , Journalist

Other books by James Joyce

A portrait of the artist as a young man by james joyce, dubliners by james joyce, finnegans wake by james joyce, our most recommended books, great expectations by charles dickens, jane eyre by charlotte brontë, wuthering heights by emily brontë, the great gatsby by f. scott fitzgerald, emma by jane austen, middlemarch by george eliot.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- What did Modernism do?

- Where is Modernism today?

- What was James Joyce’s family like?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- BBC News - Ulysses: Celebrating 100 years of a literary masterpiece

- Literary Devices - Ulysses

- Internet Archive - "Ulysses"

- Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University - Ulysses

- Academia - Introduction to Ulysses

- Table Of Contents

Ulysses , novel by Irish writer James Joyce , first published in book form in 1922. Stylistically dense and exhilarating, it is regarded as a masterpiece and has been the subject of numerous volumes of commentary and analysis. The novel is constructed as a modern parallel to Homer ’s epic poem Odyssey .

All the action of Ulysses takes place in and immediately around Dublin on a single day (June 16, 1904). The three central characters— Stephen Dedalus (the hero of Joyce’s earlier autobiographical novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man ); Leopold Bloom , a Jewish advertising canvasser; and his wife, Molly Bloom , a professional singer—are intended to be modern counterparts of Telemachus , Ulysses (Odysseus) , and Penelope , respectively, and the events of the novel loosely parallel the major events in Odysseus’s journey home after the Trojan War .

The book begins at 8:00 in the morning in a Martello tower (a Napoleonic-era defensive structure), where Stephen lives with medical student Buck Mulligan and his English friend Haines. They prepare for the day and head out. After teaching at a boys’ school, Stephen receives his pay from the ignorant and anti-Semitic headmaster, Mr. Deasy, and takes a letter from Deasy that he wants to have published in two newspapers. Afterward Stephen wanders along a beach, lost in thought.

Also that morning, Bloom brings breakfast and the mail to Molly, who remains in bed; her concert tour manager, Blazes Boylan, is to see her at 4:00 that afternoon. Bloom goes to the post office to pick up a letter from a woman with whom he has an illicit correspondence and then to the pharmacist to order lotion for Molly. At 11:00 am Bloom attends the funeral of Paddy Dignam with Simon Dedalus (Stephen’s father), Martin Cunningham, and Jack Power.

The characters in Ulysses serve as modern parallels to those in Homer ’s Odyssey . Many of them were also based on other figures from Greek mythology or early 20th-century Ireland . Here’s a guide to who’s who in Ulysses .

- Leopold Bloom : Odysseus (Ulysses)

- Stephen Dedalus : Telemachus ; St. Stephen (first Christian martyr ); Daedalus (mythical Greek craftsman); James Joyce

- Molly Bloom : Penelope ; Nora Barnacle (Joyce’s wife)

- Buck Mulligan: Antinous; Oliver St. John Gogarty (Joyce’s former roommate)

- Mr. Deasy: Nestor ; Francis Irwin (Irish headmaster and Joyce’s former employer)

- Blazes Boylan: Eurymachus; Augustus Boylan (Irish tenor); James Daly and Ted Keogh (two Irish horse dealers)

- Simon Dedalus: John Stanislaus Joyce (Joyce’s father)

- River Liffey : Bosporus

- AE : George William Russell (Irish poet and Joyce’s publisher at The Irish Homestead )

- The citizen: Cyclops ; Michael Cusack (cofounder of the Gaelic Athletic Association)

- Bella Cohen: Circe ; Ellen Cohen (English sex worker and brothel owner)

Bloom goes to a newspaper office to negotiate the placement of an advertisement, which the foreman agrees to as long as it is to run for three months. Bloom leaves to talk with the merchant placing the ad. Stephen arrives with Deasy’s letter, and the editor agrees to publish it. When Bloom returns with an agreement to place the ad for two months, the editor rejects it. Bloom walks through Dublin for a while, stopping to chat with Mrs. Breen, who mentions that Mina Purefoy is in labor. Bloom later has a cheese sandwich and a glass of wine at a pub. On his way to the National Library afterward, he spots Boylan and ducks into the National Museum.

In the National Library, Stephen discusses his theories about Shakespeare and Hamlet with the poet AE , the essayist and librarian John Eglinton, and the librarians Richard Best and Thomas Lyster. Bloom arrives, looking for a copy of an advertisement he had placed, and Buck shows up. Stephen and Buck leave to go to a pub as Bloom also departs.

Simon Dedalus and Matt Lenehan meet in the bar of the Ormond Hotel, and later Boylan arrives. Leopold had earlier seen Boylan’s car and followed it to the hotel, where he then dines with Richie Goulding. Boylan leaves with Lenehan, on his way to his assignation with Molly. Later, Bloom goes to Barney Kiernan’s boisterous pub, where he is to meet Cunningham in order to help with the Dignam family’s finances. Bloom finds himself being cruelly mocked, largely for his Jewishness, most viciously by a patron known as “the citizen.” He defends himself, and Cunningham rushes him out of the bar.

After the visit to the Dignam family, Bloom, after a brief dalliance at the beach, goes to the National Maternity Hospital to check in on Mina. He finds Stephen and several of his friends, all somewhat drunk. He joins them, accompanying them when they repair to Burke’s pub. After the bar closes, Stephen and a friend head to Bella Cohen’s brothel. Bloom later finds him there. Stephen, very drunk by now, breaks a chandelier , and, while Bella threatens to call the police, he rushes out and gets into an altercation with a British soldier, who knocks him to the ground. Bloom takes Stephen to a cabman’s shelter for food and talk, and then, long after midnight, the two head for Bloom’s home. There Bloom makes hot cocoa, and they talk. When Bloom suggests that Stephen stay the night, Stephen declines, and Bloom sees him out. Bloom then goes to bed with Molly; he describes his day to her and requests breakfast in bed.

While the allusions to the ancient work that provides the scaffolding for Ulysses are occasionally illuminating , at other times they seem designed ironically to offset the often petty and sordid concerns that take up much of Stephen’s and Bloom’s time and continually distract them from their ambitions and aims. The book also conjures up a densely realized Dublin, full of details, many of which are—presumably deliberately—either wrong or at least questionable. But all this merely forms a backdrop to an exploration of the inner workings of the mind, which refuses to acquiesce in the neatness and certainties of classical philosophy.

Although the main strength of Ulysses lies in its depth of character portrayal and its breadth of humor, the book is most famous for its use of a variant of the interior monologue known as the stream-of-consciousness technique. Joyce thereby sought to replicate the ways in which thought is often seemingly random and to illustrate that there is no possibility of a clear and straight way through life. By doing so, he opened up a whole new way of writing fiction that recognized that the moral rules by which we might try to govern our lives are constantly at the mercy of accident and chance encounter, as well as the byroads of the mind. Whether this is a statement of a specifically Irish condition or of some more universal predicament is throughout held in a delicate balance, not least because Bloom is Jewish and is thus an outsider even—or perhaps especially—in the city and country he regards as home.

Read about the obscenity court case and banning of Ulysses .

Ulysses was excerpted in The Little Review in 1918–20, at which time further publication of the book was banned , as the work was excoriated by authorities for being prurient and obscene . It was first published in book form in 1922 by Sylvia Beach , the proprietor of the Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company . There have since been other editions published, but scholars cannot agree on the authenticity of any one of them. An edition published in 1984 that supposedly corrected some 5,000 standing errors generated controversy because of the inclusion by its editors of passages not in the original text and because it allegedly introduced hundreds of new errors. Most scholars regard Ulysses as a masterwork of Modernism , while others hail it as the pivotal point of postmodernism. Perhaps the most notable of the works of analysis is Don Gifford’s Ulysses Annotated (1988).

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Seductions of “Ulysses”

The Twitter account UlyssesReader is what programmers call a “corpus-fed bot.” The corpus on which it feeds is James Joyce’s modernist epic, “ Ulysses ,” which was published a hundred years ago this month. For nine years, UlyssesReader has consumed the novel’s inner parts with relish, only to spit them out at a rate of one tweet every ten minutes. The novel’s eighteen episodes, each contrived according to an elaborate scheme of correspondences—Homeric parallels, hours of the day, organs of the body—are torn asunder. Characters are dismembered into bellies, breasts, and bottoms. When UlyssesReader reaches the end, it presents the novel’s historic signature, “Trieste-Zurich-Paris 1914-1921,” intact, like a bone fished out of the throat. Then it begins again, arranging, in its mechanical way, the tale of a young Dubliner named Stephen Dedalus and an older one named Leopold Bloom, brought together in a hospital, a brothel, a cabmen’s shelter, and, finally, the kitchen of Bloom’s home—on June 16, 1904, “an unusually fatiguing day, a chapter of accidents.”

My relationship with UlyssesReader is intense and, I suspect, typical. Waking up, sleepy and displeased, I roll over to see what it has been up to during the night. Sometimes it greets me with a sentence whose origin and significance I know with the same certainty that I know my name. The beginning of the novel, say:

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and razor lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him on the mild morning air.

Placing these sentences is simple. It is eight in the morning at the Martello tower in Sandycove. The tower, an obsolete British defense fortress, overlooks the “snotgreen,” “scrotumtightening” Irish Sea—“a great sweet mother,” Buck Mulligan intones, playing the roles of both priest and jester before an unamused Stephen Dedalus, who is grieving the death of his mother. Grasping whose point of view these sentences issue from is trickier, but key to the novel’s technical ambitions. The passage is marked by Buck’s rhetorical bombast—“stately,” “bearing a bowl”—but deflated by the gently ironizing description of him as “plump.” It was on the back of this observation that the critic Leo Bersani claimed that “Ulysses” brought to modern literature its most refined technique: a narrative perspective that was “at once seduced” by its characters’ distinctive thoughts and “coolly observant of their person.”

From these two sentences, a whole history of literature beckons—a sudden blooming of forms and genres, authors and periods, languages and nations. Why is “dressinggown,” like “scrotumtightening,” a single retracting word, as if English were steadying itself to transform into German? (A triviality, you might protest, but the trustees of the Joyce estate once sued the editor of a “reader friendly” edition of “Ulysses” that severed it into “dressing gown.”) Is the yellow gown an afterimage of Homer’s Dawn, flinging off her golden robe? What to make of that peculiar word “ungirdled”? The cords of the ungirdled gown draw my mind to the ungirdled tunics of the warriors in the Iliad; to Shakespeare’s fairy Puck, who boasts that he can “put a girdle round about the earth / in forty minutes”; to the plump, ungirdled Romans in “The Last Days of Pompeii,” by the Victorian novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton. How many novels encourage such wanderings?

“Ulysses” is all about wandering, of course, and about the loneliness that attends it. While running errands that same morning, Leopold Bloom summons a memory of his wife, Molly, thrusting into his mouth a crushed seedcake on the day he proposed to her: “I lay, full lips open, kissed her mouth. Yum. Softly she gave me in my mouth the seedcake warm and chewed. Mawkish pulp her mouth had mumbled sweet and sour with spittle. Joy: I ate it: Joy.” Yet the sweetness of his memory is soured by a sudden recollection. This is the day, he suspects, that Molly is going to have sex with the businessman Blazes Boylan, the “worst man in Dublin.” Bloom is adrift from his wife, adrift from his past self, and alone with his memory—just as readers, devouring the novel with pleasure, look up to realize that they are alone and adrift on its thrashing sea of references. “The anxiety which ‘Ulysses’ massively, encyclopedically struggles to transcend,” Bersani writes, “is that of disconnectedness”—the “traumatic seductions” of desiring to read all one would have to read to master those references. How many people have read not just Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Sterne, Fielding, Blake, Goethe, Wilde, and Yeats but also Irish, Indian, and Jewish folklore? How many are proficient in French, German, Spanish, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin? Whom do you share these connections with?

Seduced and abandoned, the reader makes one connection after another, but they affirm nothing more than Joyce’s appetite for knowledge, a cultural literacy presented as godlike in its extent. “Ulysses,” Bersani concludes, is “modernism’s most impressive tribute to the West’s long and varied tribute to the authority of the Father.” The Father’s most dutiful offspring are known as Joyceans, and the churn of the “Joyce industry” has spawned a vast apparatus of commentary that even they have deemed oppressive. “Those of us who love Joyce must also hate both him and the industrialized critical tradition that now trails in his wake,” the scholar Sean Latham has written, attempting to shake Joyce’s hold on his acolytes. But everyone knows that hating a father only strengthens his power over you.

What about those mornings when I wake up and the bot’s nocturnal emissions are unplaceable? “Desire’s wind blasts the thorntree but after it becomes from a bramblebush to be a rose upon the rood of time. Mark me now. In woman’s womb word is made flesh but in the spirit of the maker all flesh.” What? I could fetch a rumpled copy of Don Gifford’s “Ulysses Annotated” and find an allusion lurking beneath the brambles. Or I could reach for Sam Slote, Marc A. Mamigonian, and John Turner’s forthcoming “ Annotations to James Joyce’s Ulysses ” (Oxford), which, with some twelve thousand entries, is more than twice the length of the novel. But I like the idea of a hole in my knowledge of literature’s history. And I like the idea that someone, in some other fleshwarmed bed, is making connections I cannot. This is the pleasure of surrender and passivity. Or, as Bloom thinks, when he returns home that night to a bed bearing “the imprint of a human form, male, not his,” it is the pleasure of feeling “more abnegation than jealousy, less envy than equanimity.” This surrender is love. If desire is the pain of ignorance, then love, as the scholar Sam See proclaimed in a stirring response to Bersani, “is the pleasure of ignorance: the pleasure of renouncing our desire to fill the hole of knowledge, to make knowledge whole, to master those to whom we bear relation.” To relinquish mastery is to sing, as Molly does, “love’s old sweet song.”

Link copied

Knowledge and ignorance, desire and love, control and submission—these are the straits that “Ulysses” asks its readers to navigate. There are more technologies of navigation available today than when Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia Beach’s bookshop in Paris, first published the novel. There are studies, among which Anthony Burgess’s “ Re Joyce ” (1965) and Richard Ellmann’s “ Ulysses on the Liffey ” (1972) remain the most unapologetically joyous. There are the audio and visual recordings: the thrill of hearing Pegg Monahan’s low, husky voice merge with Molly’s consciousness in the 1982 Irish-public-radio production; the wonder of watching a windswept Rob Doyle atop Dalkey’s Martello tower during the Thornwillow Centennial Reading. There are the illustrations, from Matisse’s comically irrelevant ones—having never bothered to read “Ulysses,” he just drew scenes from the Odyssey—to Eduardo Arroyo’s enchanting Surrealist cartoons for “ Ulysses: An Illustrated Edition ” (Other Press) and John Morgan’s beautiful, fragile “Usylessly,” which replicates the physical form of the first edition but erases all the text. If all these projects make new ways of taking in “Ulysses” desirable, then they also retrieve the pleasure of loving it from the maw of the machine.

“Ulysses” is often described as an encyclopedic novel. “Encyclopedia in the form of farce,” Ezra Pound pronounced, comparing it to Gustave Flaubert’s “ Bouvard and Pécuchet ,” whose zany title characters fail to complete their delightfully stupid quest to master all knowledge. “Ulysses” does not depict anyone stringing together entries, yet the novel’s repetition of certain terms and phrases is hard to miss. They rise from the page like “wavewhite wedded words shimmering,” gaining in intensity and significance.

“Desire” is one of these words. If there were entries for it in “Ulysses,” sexual desire would attach to Bloom—who receives flirtatious letters, reads erotica, masturbates on the beach, and scrutinizes the mirabilis anus of nearly every female he encounters—while literary desire would attach to Stephen, the aspiring writer. “All desire to see you bring forth the work you meditate, to acclaim you Stephaneforos,” his fair-weather friend Vincent Lenehan jeers in the fourteenth episode, while they are sitting in the Holles Street Maternity Hospital, waiting for a baby to be born. Childbirth and writing, the essence of creation myths, emerge as twinned rituals in “Ulysses.”

It is tempting to think that the desire to create, whether a life or a novel, demands mastery—the exercise of control over the materials of one’s mind and body. Stephen is pricked by both this desire to master and a melancholy revolt against the artifice of knowledge. The novel’s first three chapters extend the largely autobiographical arc of the Künstlerroman project that Joyce began with the publication, in 1916, of “ A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man .” Then Stephen was merely youthful and dilettantish. Now he is young, unwashed, grieving, too clever by half, and incapable of writing. “He is going to write something in ten years,” Buck Mulligan laughs. “Will write fully tomorrow,” Stephen slurs, extremely drunk, toward the end of “Ulysses.” “I am a most finished artist.”

Only a stranded writer would make such a conceited claim. Stephen’s frustrated desire is a creative longing in search of a subject. The desire is spurred by the absence of Stephen’s own creator: his mother, who has died between the end of “Portrait” and the beginning of “Ulysses,” while he was living in gloomy, penurious self-exile in Paris. “ Amor matris: subjective and objective genitive,” Stephen thinks. The double meaning of the Latin—a mother’s love and love for a mother—doubles his sense of loss. He can neither possess nor be possessed by his creator, and he can find no pleasure yet in this unknowing, can recover nothing but pain from the wake of death. “Pain, that was not yet the pain of love, fretted his heart,” the narrator observes. Lines of Yeats that Stephen set to song at his mother’s deathbed chime through his head: “And no more turn aside and brood / Upon love’s bitter mystery.”

Stephen ignores this advice. How could a grieving child help but brood? Like Hamlet, he spends the day lost in rumination, unable to master his thoughts, and incapable of using his knowledge to create something that will fill the hole opened by death. The next episode, “Nestor,” finds him teaching history in a classroom. The children must memorize and repeat names, dates, and places of battle. Their performance of knowledge breeds cruelty; their laughter when a classmate answers incorrectly is “mirthless but with meaning.” “Yes,” Stephen thinks. “They knew: had never learned nor ever been innocent.” His mind flashes to a library he frequented in Paris, where students seemed like “fed and feeding brains about me: under glowlamps, impaled, with faintly beating feelers.” In this vision, both readers and books are irradiated, dissected, and bled dry.

“To learn one must be humble,” Stephen’s employer, Mr. Deasy, declares. “But life is the great teacher.” Deasy, though pompous, is not incorrect. Life, in “Ulysses,” is the experience of the body, from tip to toe, as it wanders through the world. It is sensation mediated by language, and language refined by sensation. This is what the lovely and challenging beginning of the next episode, “Proteus,” tries hard to seize. It opens with Stephen walking along the beach, looking around:

Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot. Snotgreen, bluesilver, rust: coloured signs. Limits of the diaphane. But he adds: in bodies. Then he was aware of them bodies before of them coloured. How? By knocking his sconce against them, sure. Go easy.

Joyce’s telescoped words—seaspawn, seawrack, snotgreen, bluesilver—create the illusion of descriptive precision. But the illusion dims when it comes time to fix definitions or concepts to them. What is seawrack? What is the essence of bluesilver? The reader can knock her sconce against these questions, but her head will crack in half before the words do. She can contemplate them only as an aesthetic experience—an invitation to rub up against the sound-images, vowels and consonants dilating luxuriously over time. Lest we become too complacent in our aestheticism, Joyce pushes his word-painting to the point of absurdity, with a “fourworded Wavespeech: seesoo, hrss, rsseeiss, ooos.” Reading the sound of the sea is no match for riding seaward on the waves.

The most evocative allegory for contemplation in “Proteus” is provided by Tatters, a dog whom Stephen watches sniff the carcass of another dog that has washed up dead on the beach: “He stopped, sniffed, stalked round it, brother, nosing closer, went round it, sniffling rapidly like a dog all over the dead dog’s bedraggled fell.” The sight is grotesque in its physical closeness and touching in its metaphysical distance. The fear, of course, is that Tatters will start to eat his brother, consuming the dog’s body just as the feeding brains in the library consume books. But Tatters is playful, curious, and tender. The way he approaches his brother—a light touch from his wet nose—answers Stephen’s silent plea toward the end of “Proteus”: “I am lonely here. O, touch me soon, now. What is the word known to all men?”

“Love, yes. Word known to all men,” Stephen says later, answering his own question. This is in the novel’s ninth episode, “Scylla and Charybdis,” which takes place in the library. Here Stephen feeds the brains of his friends with his theory of how Shakespeare, cuckolded by his wife, projected his dispossession onto “ Hamlet ,” splitting his psyche between Hamlet and the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Proudly self-conscious of his mastery of storytelling, Stephen unfurls his schema of Shakespeare’s creative spirit as both “bawd and cuckold. He acts and is acted on. Lover of an ideal or a perversion.” The chapter provides a handy gloss on “Ulysses” itself. Bloom’s marital dilemma echoes Stephen’s theory; words and images from previous chapters are dragged into his boastful speech.

A librarian, unimpressed, asks, “Do you believe your own theory?” “No,” Stephen responds. Love remains a word known to all in theory but an ethic unknown to these young men. Like the most pedantic readers, they remain stuck in preening performance of their knowingness. Getting us to believe in love requires Joyce to put his older, more experienced character into action.

The entry for “love” in the “Ulysses” encyclopedia would be naughtier and more allusive than the entry for “desire.” It would begin with the portmanteaus: lovekin, lovelock, lovelorn, lovephiltres, loveshivery, lovesoft, lovesome, and lovewords. Then the characters: the Reverend Hugh C. Love, who reveals “his grey bare hairy buttocks between which a carrot is stuck”; James Lovebirch, the author of “Fair Tyrants” and other sadomasochistic erotica. They are followed by the books (“The Beaufoy books of love”), the songs (“Love’s Old Sweet Song”), and the epigrams (“Love laughs at locksmiths,” “Plain and loved, loved for ever they say,” “Wilde’s love that dare not speak its name”). The entry, to borrow Stephen’s phrase, “dallies between conjugal love and its chaste delights and scortatory love and its foul pleasures”—the limbo where “Ulysses” lets its readers dally, with Bloom as their guide.

Love, soppy as it may seem, is the novel’s great subject. But it is not great in the way imagined by romantic young Gerty MacDowell, who, in “Nausicaa,” rapturously exposes her bottom to Bloom as he masturbates. “Her every effort would be to share his thoughts,” Gerty thinks, weaving a thick shroud of fantasy around this stranger. “For love was the master guide.” But these are a young girl’s ideals, and grownup love in “Ulysses” does not strain for perfect and possessive communion. Gerty’s clenching fantasy of Bloom evokes the schlocky story printed on the newspaper with which he wipes his ass in the fourth episode, “Calypso.” He has just delivered a note to his wife from Blazes Boylan, who Bloom knows will come to the house that afternoon.

Love is also the answer to a narrative problem: What do you do on the day you suspect, but do not want to confirm, that your wife is getting “fucked yes and damn well fucked too”? Run some errands, perhaps. Receive a flirty letter from a woman named Martha. Attend a funeral. Go to a museum. Do some work. Eat lunch. Bloom will not, as Stephen claims Shakespeare did in response to his cuckolding, write “Hamlet.” But “Ulysses” will amass a great deal of its antic, thrilling language through Bloom’s attempt to not think about and to not know about his wife’s transgression. In the eighth episode, “Lestrygonians,” Bloom, as he eats lunch, will conjure a stammering memory of the night Boylan first took Molly’s hand: “Glowworm’s la-amp is gleaming, love. Touch. Fingers. Asking. Answer. Yes. Stop. Stop.” And later: “Today. Today. Not think.” Choosing dispossession requires distraction. It makes Bloom hypervigilant toward his surroundings, opening his consciousness to the sensual gratification of words—“glowworm’s la-amp,” “touch”—that are borrowed from the novel’s idiom, gyring into Bloom’s mind. They fill the hole in his knowledge.

Bloom becomes an increasingly passive character as the day progresses, his voice and consciousness drowned out by the city and its inhabitants. In the eleventh episode, “Sirens,” he sits in a tavern and tries to respond to Martha’s letter, but the suspicion of Boylan’s imminent arrival mingles with some music he hears, shattering the privacy of his thoughts: “Tipping her tepping her tapping her topping her. Tup. Pores to dilate dilating. Tup. The joy the feel the warm the. Tup.” This, the novel proffers, is the “language of love,” and its insistence (tup, tup, tup) makes it, as Bloom responds, “utterl imposs. Underline imposs . To write today.” Nearly every one of Joyce’s narrative techniques is pressed into the service of deriving pleasure—for Bloom and for the reader—from Bloom’s pain.

The climax of his passivity comes in the twelfth episode, “Cyclops,” which takes place in a pub at the same hour Boylan is at Bloom’s house. An anonymous first-person narrator watches as the belligerent, drunken anti-Semites of Dublin, led by an Irish nationalist known as “the citizen,” goad Bloom for being half Jewish. This is the only moment in the day when he loses his composure, lashing out:

—Robbed, says he. Plundered. Insulted. Persecuted. Taking what belongs to us by right. At this very moment, says he, putting up his fist, sold by auction in Morocco like slaves or cattle. —Are you talking about the new Jerusalem? says the citizen. —I’m talking about injustice, says Bloom. . . . Force, hatred, history, all that. That’s not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it’s the very opposite of that that is really life. —What? says Alf. —Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred.

Everything that “Ulysses” is said to be “about”—colonial politics, capitalist exploitation, animal ecologies, men and women, marriage and sex—is bound up in Bloom’s affirmation of love and the virtues of turning the other cheek, or a blind eye. He is, at this juncture, being plundered by Boylan and insulted by his fellow-citizens. But he asserts himself by pulling out from a fight, “as limp as a wet rag.” His Christian heroics are at once absurd and courageous.

The metaphorical cheek becomes a literal one in “Circe,” the hallucinatory fifteenth episode, set in a brothel, where the passivity of love metamorphoses into a furious masochistic desire. Bloom has spent the day indulging his love of bottoms—spying the “white button under the butt” of his cat’s tail, ogling the “mesial groove” of a Venus statue in the museum—but in “Circe” he becomes everybody’s bottom. The brothel turns into a courtroom, and the novel into a play with stage directions and an invisible director. Bloom is tried and convicted for his lewdness; whipped and spanked; ridden like a horse, before blooming a vagina and giving birth to eight children; and then forced to drink piss. It is both painful and pleasurable not to know what happens where—whether the carnivalesque action of “Circe” lives in the story’s reality or its dreamworld, in its characters’ conscious or unconscious minds; who is in control and who has submitted; who acts and who is acted on.

The brothel is where the man with the theory of love and the man manifesting it finally come together, with Bloom helping Stephen after he has been knocked out in a brawl. It is common to see Bloom as a father in search of a son—his son, Rudy, who appears at the end of “Circe,” died years ago, eleven days after he was born—and Stephen as a son in search of a proper father. But if “Ulysses” teaches us anything it is that nobody is ever only a father or a son, and the musk of the brothel still clings to both men when they arrive at the cab shelter to have a cup of coffee. In “Circe,” Bloom offers to serve as Molly’s “business menagerer”—an offer that he later appears to pursue when he presents a seductive picture of Molly to Stephen: “Ah, yes! My wife, he intimated, plunging in medias res , would have the greatest pleasure in making your acquaintance.” The beauty of the intimation is that it is impossible for the reader to know with certainty whether it is an innocent or an illicit proposition.

It is probably a betrayal of the feminist literary tradition to pronounce the final episode of “Ulysses,” “Penelope,” the best—the funniest, most touching, arousing, and truthful—representation of a woman anyone has written in English. But it is, and the eight long, unpunctuated, and outrageous sentences of Molly Bloom’s silent monologue make much of the feminist canon look like a sewing circle for virgins and prudes. In what is often described as a gush of thought, she thinks of her husband, her past lovers, Boylan, her childhood, her children—of every experience of life.

If the earliest feminist critics of “Ulysses” were, for better or worse, struck by Molly’s eroticism, then today I am struck, and moved, by how her sexual frankness and fluidity circle around her fear of pregnancy and, nested within that fear, the death of her baby boy. Molly and Bloom share a certain horror at reproduction. “Fifteen children he had,” Bloom thinks of Stephen’s “philoprogenitive” father—the blind rutting with which people bring children into a world that cannot provide for them. In Molly’s mind, reproduction is tied to the one and only memory she actively refuses to brood upon: “I suppose I oughtnt to have buried him in that little woolly jacket I knitted crying as I was but give it to some poor child but I knew well Id never have another our 1st death too it was we were never the same since O Im not going to think myself into the glooms about that any more.”

“Could never like it again after Rudy,” Bloom thinks of his wife. It is common for critics to say that Molly and Bloom have not had sex since their son’s death, but this assertion only shows how limited the sexual imaginations of critics can be. He came on her bottom only two weeks ago and regularly kisses the “plump mellow yellow smellow melons of her rump”; judging by his attention to her “mellow yellow furrow,” he would welcome Molly’s invitation to “drag open my drawers and bulge it right out in his face as large as life he can stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part.” The hole she does not want filled is the one that reproduces—the hole that produces direct connections. “Theyre all mad to get in there where they come out of youd think they could never go far enough,” she thinks, relieved that Boylan, despite his size, “hasnt such a tremendous amount of spunk in him when I made him pull out.”