- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

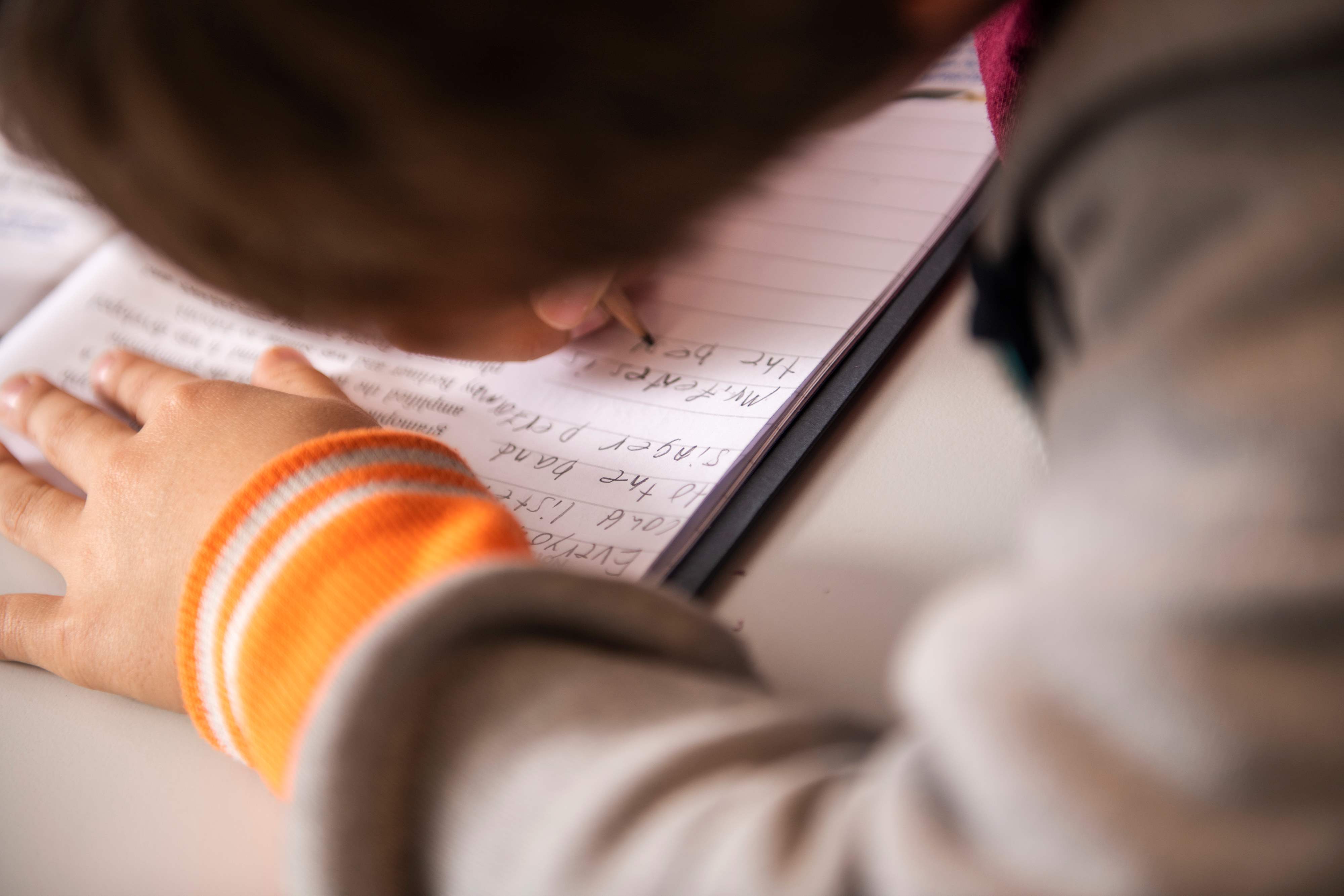

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Status | |

| Version | |

| Ad File | |

| Disable Ads Flag | |

| Environment | |

| Moat Init | |

| Moat Ready | |

| Contextual Ready | |

| Contextual URL | |

| Contextual Initial Segments | |

| Contextual Used Segments | |

| AdUnit | |

| SubAdUnit | |

| Custom Targeting | |

| Ad Events | |

| Invalid Ad Sizes |

Access provided by

Associations of time spent on homework or studying with nocturnal sleep behavior and depression symptoms in adolescents from Singapore

Download started

- Download PDF Download PDF

- Add to Mendeley

Participants

Measurements, conclusions.

- Sleep deprivation

Introduction

Participants and methods, participants and data collection, assessment of sleep behavior and time use, assessment of depression symptoms, data analysis and statistics.

| Time spent on activities (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily activities | School days | Weekends | Cohen's d | ||

| Time in bed for sleep | 6.57 ± 1.23 | 8.93 ± 1.49 | −49.0 | <0.001 | −1.73 |

| Lessons/lectures/lab | 6.46 ± 1.11 | 0.07 ± 0.39 | 194.9 | <0.001 | 7.68 |

| Homework/studying | 2.87 ± 1.46 | 4.47 ± 2.45 | −30.0 | <0.001 | −0.79 |

| Media use | 2.06 ± 1.27 | 3.49 ± 2.09 | −32.4 | <0.001 | −0.83 |

| Transportation | 1.28 ± 0.65 | 0.98 ± 0.74 | 11.4 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Co-curricular activities | 1.22 ± 1.17 | 0.22 ± 0.69 | 28.4 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| Family time, face-to-face | 1.23 ± 0.92 | 2.70 ± 1.95 | −32.5 | <0.001 | −0.97 |

| Exercise/sports | 0.86 ± 0.86 | 0.91 ± 0.97 | −2.2 | 0.031 | −0.06 |

| Hanging out with friends | 0.59 ± 0.77 | 1.24 ± 1.59 | −15.2 | <0.001 | −0.52 |

| Extracurricular activities | 0.32 ± 0.65 | 0.36 ± 0.88 | −1.9 | 0.057 | −0.06 |

| Part-time job | 0.01 ± 0.13 | 0.03 ± 0.22 | −2.4 | 0.014 | −0.08 |

- Open table in a new tab

Conflict of interest

Acknowledgments, appendix supplementary materials (1), article metrics, related articles.

- Download Hi-res image

- Download .PPT

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Information

- Download Conflict of Interest Form

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Style Guidelines for In Memoriam

- Download Online Journal CME Program Application

- NSF CME Mission Statement

- Professional Practice Gaps in Sleep Health

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Activate Online Access

- Information for Advertisers

- Career Opportunities

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

- Press Releases

- More Periodicals

- Find a Periodical

- Go to Product Catalog

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Sacrificing Sleep For Study Time Doesn’t Make the Grade

Help your teen academically by promoting sleep..

Posted September 6, 2012

- Why Is Sleep Important?

- Take our Sleep Habits Test

- Find a sleep counsellor near me

It’s back to school season, with students (and parents) saying goodbye to the freewheeling days of summer and returning to the structure of the academic year. The school routine typically includes early mornings and, often, late nights of homework and studying.

For students, there is increasing pressure to perform well academically, especially as they enter high school and college is on the horizon. Academic workloads increase, and so do time commitments to other extracurricular activities, including sports. It can be a real challenge to find enough time for all of this activity, and it’s not hard to see how bedtime gets pushed back later and later, to make room for studying.

It might seem like a reasonable sacrifice to give up a little sleep to hit the books late into the night, but new research says this strategy doesn’t work. This study found that students who stay up late doing homework are more likely to have academic problems the next day. This is true regardless of how much overall studying the student does, according to the study results.

Researchers at UCLA examined the daily sleep and study habits of 535 students in grades 9, 10, and 12. All the students were enrolled in Los Angeles schools, and represented a range of socioeconomic and ethnic groups. For two weeks, students kept diaries recording their daily study amounts and sleep amounts. They also kept track of two different types of academic problems:

Having trouble understanding material being taught in class

Doing poorly on tests, quizzes, or homework assignments

Researchers found that opting to delay bedtime in favor of studying was linked to an increased risk of both types of academic difficulty. And this was true regardless of the total amount of students’ study time.

The remedy to this problem is not to study less, but rather to create a schedule that allows for sufficient study time and sufficient sleep time. Is that easier said than done? Probably. But as these results indicate, extra study time at the expense of sleep is like to create academic problems, not solve them. And students who regularly stay up late are exposed to other risks of low sleep. Here’s some of what we know about how insufficient sleep can negatively affect teens:

Teens who don’t get enough sleep are more likely to engage in risky and unhealthful behaviors. This study found low sleep linked to increased likelihood of smoking , drinking, drug use, and fighting, among other risky behaviors.

Teens who sleep less are more likely to gain weight. We know that low sleep is associated with weight gain, in children as well as adults. This study found that teens who sleep less are more likely to consume more total calories in a day, as well as to eat higher fat foods and more snack foods than teens who get enough sleep.

Teens who are short on sleep are more likely to feel depressed and anxious. There’s substantial evidence that teens with sleep problems are at higher risk for mental health and behavioral problems. This National Sleep Foundation survey found that teens short on sleep were significantly more likely to experience depression , stress , excessive worrying, and anxiety .

Teenagers , as any parent knows, are predisposed to staying up late and sleeping late, which complicates things even further. This is a biological reality, not just a teenage preference! It’s not always easy to manage a teenager’s sleep schedule. Here are some strategies that can help:

Keep technology out of the bedroom. Electronic and digital devices have no place in the bedroom. Exposure to the light emitted by these devices is disruptive to sleep, and their presence at bedtime can keep teens awake—or even keep them engaged in activity while they are asleep!

Work backward to find the right bedtime. Teens need more sleep than adults, about 9 hours per night. To find the appropriate bedtime, start by identifying what time your teen needs to be rising from bed. From there, work backward to set the bedtime that will ensure your teenager gets enough rest.

Let them sleep in a little on the weekends—just not a lot. With biological and hormonal changes making teens inclined to sleep later, after a week of school your teenager may want to spend most of Saturday in bed. This much sleep isn’t healthy, and will actually make your teen feel more tired, not less. Such a variation from the weekday routine will throw your teen’s schedule off course. This doesn’t mean a little sleeping in isn’t okay. Letting your teenager sleep for an extra hour or two on weekend mornings is fine.

We all want our kids to study hard and achieve academic success. It’s important to remember that sleep is a critical part of the equation.

Sweet Dreams ,

Michael J. Breus, PhD

The Sleep Doctor™

www.thesleepdoctor.com

Michael J. Breus, Ph.D. , is a clinical psychologist and a diplomate of the American Board of Sleep Medicine. He is the author of Beauty Sleep.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Mattress Education Mattress Sizes Mattress Types Choosing the Best Mattress Replacing a Mattress Caring for a Mattress Mattress Disposal Mattress Accessories Adjustable Beds Mattress Sizes Mattress Types Choosing the Best Mattress Replacing a Mattress Caring for a Mattress Mattress Disposal Mattress Accessories Adjustable Beds

- Better Sleep Sleep Positions Better Sleep Guide How to Sleep Better Tips for Surviving Daylight Saving Time The Ideal Bedroom Survey: Relationships & Sleep Children & Sleep Sleep Myths

- Resources Blog Research Press Releases

- Extras The Science of Sleep Stages of Sleep Sleep Disorders Sleep Safety Consequences of Poor Sleep Bedroom Evolution History of the Mattress

- December 12, 2018

Teens, Sleep and Homework Survey Results

Better sleep council research finds that too much homework can actually hurt teens' performance in school.

- Press Releases

ALEXANDRIA, Va. , Dec. 11, 2018 – According to new research from the Better Sleep Council (BSC) – the nonprofit consumer-education arm of the International Sleep Products Association – homework, rather than social pressure, is the number one cause of teenage stress, negatively affecting their sleep and ultimately impacting their academic performance.

American teenagers said they spend 15+ hours a week on homework, and about one-third (34%) of all teens spend 20 or more hours a week. This is more than time spent at work, school clubs, social activities and sports. When asked what causes stress in their lives, about three-quarters of teens said grades/test scores (75%) and/or homework (74%) cause stress, more than self-esteem (51%), parental expectations (45%) and even bullying (15%). In fact, according to the American Psychological Association’s Stress in America™ Survey, during the school year, teenagers say they experience stress levels higher than those reported by adults.

Further, more than half (57%) of all teenagers surveyed do not feel they get enough sleep. Seventy-nine percent reported getting 7 hours of sleep or less on a typical school night, more than two-thirds (67%) say they only get 5 to 7 hours of sleep on a school night, and only about one in five teens is getting 8 hours of sleep or more. Based on the BSC’s findings, the more stressed teenagers feel, the more likely they are to get less sleep, go to bed later and wake up earlier. They are also more likely to have trouble going to sleep and staying asleep – more often than their less-stressed peers.

“We’re finding that teenagers are experiencing this cycle where they sacrifice their sleep to spend extra time on homework, which gives them more stress – but they don’t get better grades,” said Mary Helen Rogers , vice president of marketing and communications for the Better Sleep Council. “The BSC understands the impact sleep has on teenagers’ overall development, so we can help them reduce this stress through improved sleep habits.”

The BSC recommends that teens between the ages of 13-18 get 8-10 hours of sleep per night. For teens to get the sleep their bodies need for optimal school performance, they should consider the following tips:

- Establish a consistent bedtime routine . Just like they set time aside for homework, they should schedule at least 8 hours of sleep into their daily calendars. It may be challenging in the beginning, but it will help in the long run.

- Keep it quiet in the bedroom. It’s easier to sleep when there isn’t extra noise. Teens may even want to wear earplugs if their home is too noisy.

- Create a relaxing sleep environment. Make sure the bedroom is clutter-free, dark and conducive to great sleep. A cool bedroom, between 65 and 67 degrees , is ideal to help teens sleep.

- Cut back on screen time. Try cutting off screen time at least an hour before bed. The blue light emitted from electronics’ screens disturbs sleep.

- Examine their mattress. Since a mattress is an important component of a good night’s sleep, consider replacing it if it isn’t providing comfort and support, or hasn’t been changed in at least seven years.

Other takeaways on the relationship between homework, stress and sleep in teenagers include:

- Teens who feel more stress (89%) are more likely than less-stressed teens (65%) to say homework causes them stress in their lives.

- More than three-quarters (76%) of teens who feel more stress say they don’t feel they get enough sleep – which is significantly higher than teens who are not stressed, since only 42% of them feel they don’t get enough sleep.

- Teens who feel more stress (51%) are more likely than less-stressed teens (35%) to get to bed at 11 p.m. or later. Among these teens who are going to bed later, about 33% of them said they are waking up at 6:00 a.m. or earlier.

- Students who go to bed earlier and awaken earlier perform better academically than those who stay up late – even to do homework.

About the BSC The Better Sleep Council is the consumer-education arm of the International Sleep Products Association, the trade association for the mattress industry. With decades invested in improving sleep quality, the BSC educates consumers on the link between sleep and health, and the role of the sleep environment, primarily through www.bettersleep.org , partner support and consumer outreach.

Related Posts

The State of America’s Sleep: COVID-19 and Sleep

The state of america’s sleep: isolation and sleep, the state of america’s sleep.

ABOUT THE BETTER SLEEP COUNCIL

- Mattress Education

- Better Sleep

- Privacy Policy

- Confidentiality Statement

- Breathing Disorders

- Hypersomnias

- Movement Disorders

- Circadian Rhythm Disorders

- Parasomnias

- In-Lab Tests

- Home Based/Out of Lab

- Connected Care

- Consumer Sleep Tracking

- Therapy Devices

- Pharmaceuticals

- Surgeries & Procedures

- Behavioral Sleep Medicine

- Demographics

- Sleep & Body Systems

- Prevailing Attitudes

- Laws & Regulations

- Human Resources

- White Papers

Select Page

Early Start Times, Homework Impact Sleep for Teens

Dec 11, 2018 | Age | 0 |

New survey data released from Sleep Cycle, an alarm clock app, reveals how school schedules affect the quality and quantity of sleep for kids and teens.

The survey of more than 1,000 US adults and teens conducted by Propeller Research on behalf of Sleep Cycle in September 2018 found that schoolwork keeps kids and teens up too late, early school start times have them falling asleep in class, and even teens are on board with nap time.

Americans Kids Aren’t Getting Enough Sleep

The majority of parents (70%) agree that their children need a minimum of 8-9 hours of sleep to be well-rested, but nearly half (46%) report that their children get 7 hours or less.

Additionally, while more than three-quarters (77%) of American parents got naps when they were children in kindergarten, 4 in 10 say their child did not.

When they don’t get enough sleep, parents report that their children:

- Are moody — 64%

- Are grumpy and disagreeable — 61%

- Get into more trouble at school — 28%

- Make worse life choices — 20%

- Homework doesn’t help: The vast majority (88%) of teens say they must stay up late to finish school projects — 59% on a weekly or daily basis.

Late to Bed and Early to Rise

School start times also have more than a little to do with it:

- More than half (52%) of American parents and 61% of American teens think school starts too early.

- 55% of teens feel their school work suffers because of the early start time

- 59% say that early school start times inhibit them from being productive later in the day

- 70% feel they would have more productive school days if school started later — 64% of parents agree

- About a quarter of teens (27%) say they begin to feel alert after 9 am, but the majority (39%) don’t start feeling alert until after 10 am.

- Another 10% say they don’t ever feel alert in class.

Are Naps the Answer?

Almost half (46%) of parents feel the school day is also too long. Teens agree:

- 87% have had difficulty staying awake during class because they are tired

- More than two-thirds (69%) have actually fallen asleep

- 56% report feeling worn out at the end of each school day

- All but 3% say they come home tired at least one day a week

- More than three-quarters (76%) of parents feel their child would benefit from a designated nap or rest time at school — teens included. The vast majority (78%) of teens agree that they would benefit from a nap or rest in the course of the school day.

“American students are burning the candle at both ends—staying up late to do homework and waking up early to be back in class. It’s a vicious cycle,” says Carl Johan Hederoth, CEO of Sleep Cycle, in a release. “Parents can help by trying to establish a regular bedtime and by using Sleep Cycle to wake kids in their lightest phase of sleep so they can start each day feeling refreshed, even for those early classes.”

Related Posts

Tired Teens 4.5 Times More Likely to Commit Crimes as Adults

February 27, 2017

A Sleep Expert Reveals the Ideal Start Time for Work and School

December 30, 2015

Experts Unravel Sleep’s Role in Brain Aging During Australia’s Sleep Health Week

October 9, 2023

Apnea Sciences Expands Into New Corporate Offices

December 24, 2014

Upcoming Events

Society of behavioral sleep medicine 6th annual scientific conference, collaboration cures 2024, championship updates in sleep medicine 2024, 2024 texas society of sleep professionals conference at epic central, dentistry on the rise 2024.

A Few Ideas for Dealing with Late Work

August 4, 2019

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Listen to this post as a podcast:

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

Most of my 9-week grading periods ended the same way: Me and one or two students, sitting in my quiet, empty classroom together, with me sitting at the computer, the students nearby in desks, methodically working through piles of make-up assignments. They would be focused, more focused than I’d seen them in months, and the speed with which they got through the piles was stunning.

As they finished each assignment I took it, checked it for accuracy, then entered their scores—taking 50 percent off for being late—into my grading program. With every entry, I’d watch as their class grade went up and up: from a 37 percent to a 41, then to 45, then to 51, and eventually to something in the 60s or even low 70s, a number that constituted passing, at which point the process would end and we’d part ways, full of resolve that next marking period would be different.

And the whole time I thought to myself, This is pointless . They aren’t learning anything at all. But I wasn’t sure what else to do.

For as long as teachers have assigned tasks in exchange for grades, late work has been a problem. What do we do when a student turns in work late? Do we give some kind of consequence or accept assignments at any time with no penalty? Do we set up some kind of system that keeps students motivated while still holding them accountable? Is there a way to manage all of this without driving ourselves crazy?

To find answers, I went to Twitter and asked teachers to share what works for them. What follows is a summary of their responses. I wish I could give individual credit to each person who offered ideas, but that would take way too long, and I really want you to get these suggestions now! If you’ve been unsatisfied with your own approach to late work, you should find some fresh ideas here.

First, a Few Questions About Your Grades

Before we get into the ways teachers manage late work, let’s back up a bit and consider whether your overall program of assignments and grading is in a healthy place. Here are some questions to think about:

- What do your grades represent? How much of your grades are truly based on academic growth, and how much are based mostly on compliance? If they lean more toward compliance, then what you’re doing when you try to manage late work is basically a lot of administrative paper pushing, rather than teaching your content. Although it’s important for kids to learn how to manage deadlines, do you really want an A in your course to primarily reflect the ability to follow instructions? If your grades are too compliance-based, consider how you might shift things so they more accurately represent learning. (For a deeper discussion of this issue, read How Accurate Are Your Grades? )

- Are you grading too many things? If you spend a lot of time chasing down missing assignments in order to get more scores in your gradebook, it could be that you’re grading too much. Some teachers only enter grades for major, summative tasks, like projects, major writing assignments, or exams. Everything else is considered formative and is either ungraded or given a very low point value for completion, not graded for accuracy; it’s practice . For teachers who are used to collecting lots of grades over a marking period, this will be a big shift, and if you work in a school where you’re expected to enter grades into your system frequently, that shift will be even more difficult. Convincing your students that ungraded practice is worthwhile because it will help their performance on the big things will be another hurdle. With all of that said, reducing the number of scored items will make your grades more meaningful and cut way down on the time you spend grading and managing late work.

- What assumptions do you make when students don’t turn in work? I’m embarrassed to admit that when I first started teaching, I assumed most students with missing work were just unmotivated. Although this might be true for a small portion of students, I no longer see this as the most likely reason. Students may have issues with executive function and could use some help developing systems for managing their time and responsibilities. They may struggle with anxiety. Or they may not have the resources—like time, space, and technology—to consistently complete work at home. More attention has been paid lately to the fact that homework is an equity issue , and our policies around homework should reflect an understanding that all students don’t have access to the same resources once they leave school for the day. Punitive policies that are meant to “motivate” students don’t take any of these other issues into consideration, so if your late work penalties don’t seem to be working, it’s likely that the root cause is something other than a lack of motivation.

- What kind of grading system is realistic for you ? Any system you put in place requires YOU to stay on top of grading. It would be much harder to assign penalties, send home reminders, or track lateness if you are behind on marking papers by a week, two weeks, even a month. So whatever you do, create a plan that you can actually keep up with.

Possible Solutions

1. penalties.

Many teachers give some sort of penalty to students for late work. The thinking behind this is that without some sort of negative consequence, too many students would wait until the end of the marking period to turn work in, or in some cases, not turn it in at all. When work is turned in weeks or even months late, it can lose its value as a learning opportunity because it is no longer aligned with what’s happening in class. On top of that, teachers can end up with massive piles of assignments to grade in the last few days of a marking period. This not only places a heavy burden on teachers, it is far from an ideal condition for giving students the good quality feedback they should be getting on these assignments.

Several types of penalties are most common:

Point Deductions In many cases, teachers simply reduce the grade as a result of the lateness. Some teachers will take off a certain number of points per day until they reach a cutoff date after which the work will no longer be accepted. One teacher who responded said he takes off 10 percent for up to three days late, then 30 percent for work submitted up to a week late; he says most students turn their work in before the first three days are over. Others have a standard amount that comes off for any late work (like 10 percent), regardless of when it is turned in. This policy still rewards students for on-time work without completely de-motivating those who are late, builds in some accountability for lateness, and prevents the teacher from having to do a lot of mathematical juggling with a more complex system.

Parent Contact Some teachers keep track of late work and contact parents if it is not turned in. This treats the late work as more of a conduct issue; the parent contact may be in addition to or instead of taking points away.

No Feedback, No Re-Dos The real value of homework and other smaller assignments should be the opportunity for feedback: Students do an assignment, they get timely teacher feedback, and they use that feedback to improve. In many cases, teachers allow students to re-do and resubmit assignments based on that feedback. So a logical consequence of late work could be the loss of that opportunity: Several teachers mentioned that their policy is to accept late work for full credit, but only students who submit work on time will receive feedback or the chance to re-do it for a higher grade. Those who hand in late work must accept whatever score they get the first time around.

2. A Separate Work Habits Grade

In a lot of schools, especially those that use standards-based grading, a student’s grade on an assignment is a pure representation of their academic mastery; it does not reflect compliance in any way. So in these classrooms, if a student turns in good work, it’s going to get a good grade even if it’s handed in a month late.

But students still need to learn how to manage their time. For that reason, many schools assign a separate grade for work habits. This might measure factors like adherence to deadlines, neatness, and following non-academic guidelines like font sizes or using the correct heading on a paper.

- Although most teachers whose schools use this type of system will admit that students and parents don’t take the work habits grade as seriously as the academic grade, they report being satisfied that student grades only reflect mastery of the content.

- One school calls their work habits grade a “behavior” grade, and although it doesn’t impact GPA, students who don’t have a certain behavior grade can’t make honor roll, despite their actual GPA.

- Several teachers mentioned looking for patterns and using the separate grade as a basis for conferences with parents, counselors, or other stakeholders. For most students, there’s probably a strong correlation between work habits and academic achievement, so separating the two could help students see that connection.

- Some learning management systems will flag assignments as late without necessarily taking points off. Although this does not automatically translate to a work habits grade, it indicates the lateness to students and parents without misrepresenting the academic achievement.

3. Homework Passes

Because things happen in real life that can throw anyone off course every now and then, some teachers offer passes students can use to replace a missed assignment.

- Most teachers only offer these passes to replace low-point assignments, not major ones, and they generally only offer 1 to 3 passes per marking period. Homework passes can usually only recover 5 to 10 percent of a student’s overall course grade.

- Other teachers have a policy of allowing students to drop one or two of their lowest scores in the gradebook. Again, this is typically done for smaller assignments and has the same net effect as a homework pass by allowing everyone to have a bad day or two.

- One teacher gives “Next Class Passes” which allow students one extra day to turn in work. At the end of every marking period she gives extra credit points to students who still have unused passes. She says that since she started doing this, she has had the lowest rate ever of late work.

4. Extension Requests

Quite a few teachers require students to submit a written request for a deadline extension rather than taking points off. With a system like this, every student turns something in on the due date, whether it’s the assignment itself or an extension request.

- Most extension requests ask students to explain why they were unable to complete the assignment on time. This not only gives the students a chance to reflect on their habits, it also invites the teacher to help students solve larger problems that might be getting in the way of their academic success.

- Having students submit their requests via Google Forms reduces the need for paper and routes all requests to a single spreadsheet, which makes it easier for teachers to keep track of work that is late or needs to be regraded.

- Other teachers use a similar system for times when students want to resubmit work for a new grade.

5. Floating Deadlines

Rather than choosing a single deadline for an assignment, some teachers assign a range of dates for students to submit work. This flexibility allows students to plan their work around other life activities and responsibilities.

- Some teachers offer an incentive to turn in work in the early part of the time frame, such as extra credit or faster feedback, and this helps to spread out the submissions more evenly.

- Another variation on this approach is to assign a batch of work for a whole week and ask students to get it in by Friday. This way, students get to manage when they get it done.

- Other names mentioned for this strategy were flexible deadlines , soft deadlines , and due windows .

6. Let Students Submit Work in Progress

Some digital platforms, like Google Classroom, allow students to “submit” assignments while they are still working on them. This allows teachers to see how far the student has gotten and address any problems that might be coming up. If your classroom is mostly paper-based, it’s certainly possible to do this kind of thing with paper as well, letting students turn in partially completed work to demonstrate that an effort has been made and show you where they might be stuck.

7. Give Late Work Full Credit

Some teachers accept all late work with no penalty. Most of them agree that if the work is important, and if we want students to do it, we should let them hand it in whenever they get it done.

- Some teachers fear this approach will cause more students to stop doing the work or delay submission until the end of a marking period, but teachers who like this approach say they were surprised by how little things changed when they stopped giving penalties: Most students continued to turn work in more or less on time, and the same ones who were late under the old system were still late under the new one. The big difference was that the teacher no longer had to spend time calculating deductions or determining whether students had valid excuses; the work was simply graded for mastery.

- To give students an incentive to actually turn the work in before the marking period is over, some teachers will put a temporary zero in the gradebook as a placeholder until the assignment is turned in, at which point the zero is replaced with a grade.

- Here’s a twist on the “no penalty” option: Some teachers don’t take points off for late work, but they limit the time frame when students can turn it in. Some will not accept late work after they have graded and returned an assignment; at that point it would be too easy for students to copy off of the returned papers. Others will only accept late work up until the assessment for the unit, because the work leading up to that is meant to prepare for that assessment.

8. Other Preventative Measures

These strategies aren’t necessarily a way to manage late work as much as they are meant to prevent it in the first place.

- Include students in setting deadlines. When it comes to major assignments, have students help you determine due dates. They may have a better idea than you do about other big events that are happening and assignments that have been given in other classes.

- Stop assigning homework. Some teachers have stopped assigning homework entirely, recognizing that disparities at home make it an unfair measurement of academic mastery. Instead, all meaningful work is done in class, where the teacher can monitor progress and give feedback as needed. Long-term projects are done in class as well, so the teacher is aware of which students need more time and why.

- Make homework optional or self-selected. Not all students need the same amount of practice. You may be able to get your students to assess their own need for additional practice and assign that practice to themselves. Although this may sound far-fetched, in some classes, like this self-paced classroom , it actually works, because students know they will be graded on a final assessment, they get good at determining when they need extra practice.

With so many different approaches to late work, what’s clear is that there are a lot of different schools of thought on grading and assessment, so it’s not a surprise that we don’t always land on the best solution on the first try. Experiment with different systems, talk to your colleagues, and be willing to try something new until you find something that works for you.

Further Reading

20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half This free e-book is full of ideas that can help with grading in general.

On Your Mark: Challenging the Conventions of Grading and Reporting Thomas R. Guskey This book came highly recommended by a number of teachers.

Hacking Assessment: 10 Ways to Go Gradeless in a Traditional Grades School Starr Sackstein

Come back for more. Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half , the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

What to Read Next

Categories: Classroom Management , Instruction , Podcast

Tags: assessment , organization

53 Comments

I teach high school science (mine is a course that does not have an “end of course” test so the stakes are not as high) and I teach mostly juniors and seniors. Last year I decided not to accept any late work whatsoever unless a student is absent the day it is assigned or due (or if they have an accomodation in a 504 or IEP – and I may have had one or two students with real/documented emergencies that I let turn in late.) This makes it so much easier on me because I don’t have to keep up with how many days/points to deduct – that’s a nightmare. It also forces them to be more responsible. They usually have had time to do it in class so there’s no reason for it to be late. Also, I was very frustrated with homework not being completed and I hated having to grade it and keep up with absent work. So I don’t “require” homework (and rarely assign it any more) but if students do ALL (no partial credit) of it they get a 100% (small point value grade), if they are absent or they don’t do it they are exempt. So it ends up being a sort of extra credit grade but it does not really penalize students who don’t do it. When students ask me for extra credit (which I don’t usually give), the first thing I ask is if they’ve done all the homework assigned. That usually shuts down any further discussion. I’ve decided I’m not going to spend tons of time chasing and calculating grades on small point values that do not make a big difference in an overall grade. 🙂

Do I understand correctly….

Homework is not required. If a student fully completes the HW, they will earn full points. If the student is absent or doesn’t do it, they are excused. Students who do complete the HW will benefit a little bit in their overall grade, but students who don’t compete the work will not be penalized. Did I understand it correctly?

Do you stipulate that a student must earn a certain % on the assignment to get the full points? What about a student who completed an assignment but completes the entire thing incorrectly? Still full credit? Or an opportunity to re-do?

Thank you in advance.

From reading this blog post I was thinking the same thing. When not penalizing students for homework do you have students who do turn it in getting extra points in class?

From what I have seen, if there is a benefit for turning in homework and students see this benefit more will try to accomplish what the homework is asking. So avoid penalization is okay, but make sure the ones turning it in are getting rewarded in some way.

The other question regarding what to do with students who may not be completing the assignments correctly, you could use this almost as a formative assessment. You could still give them the credit but use this as a time for you to focus on that student a little more and see where he/she isn’t understanding the content.

Our school has a system called Catch Up Cafe. Students with missing work report to a specific teacher during the first 15 minutes of lunch to work on missing work. Students upgrade to a Wednesday after school time if they have accumulated 4 or more missing assignments on any Monday. They do not have to serve if they can clear ALL missing work by the end of the day Wednesday. Since work is not dragging out for a long period of time, most teachers do not take off points.

How do you manage the logistics of who has missing and how many assignments are needed to be completed-to make sure they are attending the Catch up Cafe or Wednesday after school? How do you manage the communication with parents?

When a student has missing work it can be very difficult to see what he/she is missing. I always keep a running record of all of their assignments that quarter and if they miss that assigement I keep it blank to remind myself there was never a submission. Once I know that this student is missing this assignment I give them their own copy and write at the top late. So once they do turn it in I know that it’s late and makes grading it easier.

There are a lot of different programs that schools use but I’ve always kept a paper copy so I have a back-up.

I find that the worst part of tracking make-up work is keeping tabs on who was absent for a school activity, illness or other excused absence, and who just didn’t turn in the assignment. I obviously have to accept work turned in “late” due to an excused absence, but I can handle the truly late work however I wish. Any advice on simplifying tracking for this?

I tell my students to simply write “Absent (day/s)” at the top of the paper. I remind them of this fairly regularly. That way, if they were absent, it’s their responsibility to notify me, and it’s all together. If you create your own worksheets, etc., you could add a line to the top as an additional reminder.

It might be worth checking out Evernote .

In order to keep track of what type of missing assignments, I put a 0 in as a grade so students and parents know an assignment was never submitted. If a student was here on the due date and day assignment was given then it is a 0 in the grade book. If a student was absent the day the assignment was given or when it was due, I put a 00 in the grade book. This way I know if it was because of an absence or actual no work completed.

This is exactly what I do. Homework can only count 10% in our district. Claims that kids fail due to zeros for homework are specious.

This is SUCH a difficult issue and I have tried a few of the suggested ways in years past. My questions is… how do we properly prepare kids for college while still being mindful of the inequities at home? We need to be sure that we are giving kids opportunity, resources, and support, but at the same time if we don’t introduce them to some of the challenges they will be faced with in college (hours of studying and research and writing regardless of the hours you might have to spend working to pay that tuition), are we truly preparing them? I get the idea of mastery of content without penalty for late work and honestly that is typically what I go with, but I constantly struggle with this and now that I will be moving from middle to high school, I worry even more about the right way to handle late work and homework. I don’t want to hold students back in my class by being too much of a stickler about seemingly little things, but I don’t want to send them to college unprepared to experience a slap in the face, either. I don’t want to provide extra hurdles, but how do I best help them learn how to push through the hurdles and rigor if they aren’t held accountable? I always provide extra time after school, at lunch, etc., and have also experienced that end of term box checking of assignments in place of a true learning experience, but how do we teach them the importance of using resources, asking for help, allowing for mistakes while holding them to standards and learning work habits that will be helpful to them when they will be on their own? I just don’t know where the line is between helping students learn the value of good work habits and keeping them from experiencing certain challenges they need to understand in order to truly get ahead.

Thanks for sharing – I can tell how much you care for your students, wanting them to be confident independent learners. What I think I’m hearing is perhaps the struggle between that fine line of enabling and supporting. When supporting kids, whether academically or behaviorally, we’re doing something that assists or facilitates their growth. So, for example, a student that has anxiety or who doesn’t have the resources at home to complete an assignment, we can assist by giving that student extra time or an alternative place to complete the assignment. This doesn’t lower expectations, it just offers support to help them succeed.

Enabling on the other hand, puts systems in place that don’t involve consequences, which in turn allow the behaviors to continue. It involves excuses and solving problems for others. It may be about lowering expectations and letting people get by with patterns of behavior.

Late work is tricky. The article does mention the importance of time management, which is why separating academic grades from work habits is something a lot of schools are doing. Sometimes real life happens and kids need a “pass.” If whatever you’re doing seems to be helping to support a student rather than enabling patterns, then that might help you distinguish between that fine line. Hope this helps!

Thank you again for such a great post. Always high-quality, relevant, and helpful. I so appreciate you and the work you do!

So glad to hear you enjoyed the post, Liz! I’ll make sure Jenn sees this.

I thought that these points brought up about receiving late work were extremely helpful and I hope that every classroom understands how beneficial these strategies could be.

When reading the penalties section under point deductions it brought up the idea of taking points off slowly as time goes by. Currently in my classroom the only point deduction I take off is 30% of the total grade after it is received late. No matter how much time has gone by in that grading period it will have 30% off the total.

I’m curious if changing this technique to something that would increase the percentage off as time goes by will make students turn in their work on time.

My question to everyone is which grading technique would be more beneficial for the students? Do you believe that just taking off 30% for late work would help students more when turning in their work or do you think that as time goes by penalizing their final score will have students turn in their work more?

If anyone has any answers it would be extremely beneficial.

Thank you, Kirby

When I was in school my school did 1/3 of a grade each day it was like. So 1 day late A >A-. Two days late: A->>B+ so on and so forth. This worked really well for me because I knew that I could still receive a good grade if I worked hard on an assignment, even if it was a day or two late.

I dread it when I have missing work or unsubmitted work. I would try to get a last-minute effort to chase those needed pieces of work which could be done from those students housed in dorms on campus. It is better than not failing them for lacking to turn in graded submissions or taking scheduled quizzes. I dread this not for the students, sadly, but for likely call to explain why I did not keep physical evidence of students’ supposed learning. In my part of the globe, we have a yearly “quality assurance” audit by the country’s educational authorities or their representatives.

I am a pre-service teacher and I am in the process of developing my personal philosophies in education, including the topic of late work. I will be certified as a secondary social studies teacher and would like to teach in a high school. Your post brought my attention to some important insights about the subject. For example, before this post I had not thought to use feedback as a way to incentivize homework submission on time. This action coupled with the ability to re-do assignments is a great way to emphasize the importance of turning work in on time. I do have a follow-up question, how do you adequately manage grading re-do’s and feedback on all assignments? What kinds of organizational and time-management strategies do you use as a teacher? Further, how much homework do you assign when providing this as an option?

Additionally, have you administered or seen the no penalty and homework acceptance time limit in practice (for example, all homework must be turned in by the unit test)? I was curious if providing a deadline to accept all homework until the unit test may result in an access of papers I need to grade. From your experience, what practice(s) have you seen work well in the classroom?

My goal is to prepare students for life beyond high school and to support their intellectual, social, and emotional development during their high school learning experience. Similar to a previous commenter (Kate), I am also trying to define a balance between holding students accountable in order to best prepare them for their future lives and providing opportunities to raise their grade if they are willing to do the work.

Hey Jessica, you have some great questions. I’d recommend checking out the following blog posts from Jenn that will help you learn more about keeping track of assessments, differentiation, and other aspects of grading: Kiddom: Standards-based Grading Made Wonderful , Could You Teach Without Grades , Boost Your Assessment Power with GradeCam , and Four Research-Based Strategies Every Teacher Should be Using . I hope this helps you find answers to your questions!

Overall I found this article extremely helpful and it actually reinforced many ideas I already had about homework and deadlines. One of my favorite teachers I had in high school was always asking for our input on when we felt assignments should be due based on what extra curricular activities were taking place in a given time period. We were all extremely grateful for his consideration and worked that much harder on the given assignments.

While it is important to think about our own well-being when grading papers, I think it is just as important (if not more) to be conscious of how much work students might have in other classes or what students schedules are like outside of school. If we really want students to do their best work, we need to give them enough time to do the work. This will in turn, help them care more about the subject matter and help them dive deeper. Obviously there still needs to be deadlines, but it does not hurt to give students some autonomy and say in the classroom.

Thanks for your comment Zach. I appreciate your point about considering students’ involvement in extracurricular activities and other responsibilities they may have outside the school day. It’s definitely an important consideration. The only homework my son seemed to have in 8th grade was for his history class. I agree that there’s a need for teachers to maintain more of a balance across classes when it comes to the amount of homework they give to students.

Thank you for an important, thought-provoking post! As a veteran teacher of 20+ years, I have some strong opinions about this topic. I have always questioned the model of ‘taking points off’ for late work. I do not see how this presents an accurate picture of what the student knows or can do. Shouldn’t he be able to prove his knowledge regardless of WHEN? Why does WHEN he shows you what he knows determine WHAT he knows?

Putting kids up against a common calendar with due dates and timelines, regardless of their ability to learn the material at the same rate is perhaps not fair. There are so many different situations facing our students – some students have challenges and difficulty with deadlines for a plethora of potential reasons, and some have nothing but support, structure, and time. When it comes to deadlines – Some students need more time. Other students may need less time. Shouldn’t all students have a chance to learn at a pace that is right for them? Shouldn’t we measure student success by demonstrations of learning instead of how much time it takes to turn in work? Shouldn’t students feel comfortable when it is time to show me what they’ve learned, and when they can demonstrate they’ve learned it, I want their grade to reflect that.

Of course we want to teach students how to manage their time. I am not advocating for a lax wishy-washy system that allows for students to ‘get to it when they get to it’. I do believe in promoting work-study habits, and using a separate system to assign a grade for responsibility, respect, management, etc is a potential solution. I understand that when introducing this type of system, it may be tough to get buy-in from parents and older students who have traditionally only looked at an academic grade because it is the only piece of the puzzle that impacts GPA. Adopting a separate work-study grading system would involve encouraging the entire school community – starting at the youngest level – to see its value. It would be crucial for the school to promote the importance of high level work-study habits right along side academic grades.

I teach a specials course to inner city middle schoolers at a charter school. All students have to take my class since it is one of the core pillars of the school’s culture and mission. Therefore it is a double edge sword. Some students and parents think it is irrelevant like an art or music class but will get upset to find out it isn’t just an easy A class. Other students and parents love it because they come to our charter school just to be in this class that isn’t offered anywhere else in the state, except at the college level.

As you may have already guessed, I see a lot of students who don’t do the work. So much that I no longer assign homework, which the majority would not be able to do independently anyways or may develop the wrong way of learning the material, due to the nature of the subject. So everything is done in the classroom together as a class. And then we grade together to reinforce the learning. This is why I absolutely do not accept missing work and there is no reason for late work. Absent students make up the work by staying after school upon their return or they can print it off of Google classroom at home and turn in by the end of the day of their return. Late and missing work is a big issue at our school. I’ve had whole classrooms not do the work even as I implemented the new routine. Students will sit there and mark their papers as we do it in the classroom but by the end they are not handing it in because they claim not to have anything to hand in. Or when they do it appears they were doing very little. I’d have to micromanage all 32 students every 5 minutes to make sure they were actually doing the work, which I believe core teachers do. But that sets a very bad precedent because I noticed our students expect to be handheld every minute or they claim they can’t do the work. I know this to be the case since before this class I was teaching a computer class and the students expected me to sit right next to them and give them step-by-step instructions of where to click on the screen. They simply could not follow along as I demonstrated on the Aquos board. So I do think part of the problem is the administrators’ encouraging poor work ethics. They’re too focused on meeting proficient standard to the point they want teachers to handhold students. They also want teachers to accept late and missing work all the way until the end of each quarter. Well that’s easy if you only have a few students but when you have classrooms full of them, that means trying to grade 300+ students multiplied by “x” amount of late/missing work the week before report card rolls out – to which we still have to write comments for C- or below students. Some of us teach all the grade levels 6-8th. And that has actually had negative effects because students no longer hold themselves accountable.

To be honest, I really do think this is why there is such a high turnover rate and teachers who started giving busy work only. In the inner city, administrators only care about putting out the illusion of proficiency while students and parents don’t want any accountability for their performance. As soon as a student fails because they have to actually try to learn (which is a risk for failing), the parent comes in screaming.

Yea, being an Art teacher you lost me at “ irrelevant like an art or music .”

I teach middle school in the inner city where missing and late work is a chronic issue so the suggestions and ideas above do not work. Students and parents have become complacent with failing grades so penalizing work isn’t going to motivate them to do better the next time. The secret to teaching in the inner city is to give them a way out without it becoming massive work for you. Because trust me, if you give them an inch they will always want a mile at your expense. Depending on which subject you teach, it might be easier to just do everything in class. That way it becomes an all or nothing grade. They either did or didn’t do the work. No excuses, no chasing down half the school through number of calls to disconnected phone numbers and out of date emails, no explaining to parents why Johnny has to stay after school to finish assignments when mom needs him home to babysit or because she works second shift and can’t pick him up, etc. Students have no reason for late work or for missing work when they were supposed to do it right there in class. Absent students can catch up with work when they return.

Milton, I agree with all of what you are saying and have experienced. Not to say that that is for all students I have had, but it is a slow progression as to what is happening with students and parents as years go by. I understand that there are areas outside of the classroom we cannot control and some students do not have certain necessities needed to help them but they need to start learning what can they do to help themselves. I make sure the students know they can come and talk to me if needing help or extra time, tutor after school and even a phone number to contact along with email if needing to ask questions or get help. But parents and students do not use these opportunities given until the week before school ends and are now wanting their student to pass and what can be done. It is frustrating and sad. I let students and parents know my expectation up front and if they do not take the opportunity to talk to me then the grade they earned is the result.

I am a special education resource teacher and late work/missing work happens quite a lot. After reading this article, I want to try a few different things to help minimize this issue. However, I am not the one making the grades or putting the grades in. I am just giving the work to the students in small group settings and giving them more access to the resources they need to help them be successful on these assignments based on their current IEP. I use a make-up folder, and usually I will pull these students to work on their work during a different time than when I regularly pull them. That way they do not miss the delivery of instruction they get from me and it does not punish my other students either if there is make-up work that needs to be completed. I try to give my students ample time to complete their work, so there is no excuse for them not to complete it. If they are absent, then I pull them at a time that they can make it up.

I too agree with that there’s a need for teachers to maintain more of a balance across classes when it comes to the amount of homework they give to students.

I had a few teachers who were willing to tolerate lateness in favor of getting it/understanding the material. Lastly, my favorite teacher was the one who gave me many chances to do rewrites of a ‘bad essay’ and gave me as much time as needed (of course still within like the semester or even month but I never took more than two weeks) because he wanted me to do well. I ended up with a 4 in AP exam though so that’s good.

Late work has a whole new meaning with virtual learning. I am drowning in late work (via Google Classroom). I don’t want to penalize students for late work as every home situation is different. I grade and provide feedback timely (to those who submitted on time). However, I am being penalized every weekend and evening as I try to grade and provide feedback during this time. I would love some ideas.

Hi Susan! I’m in the same place–I have students who (after numerous reminders) still haven’t submitted work due days…weeks ago, and I’m either taking time to remind them again or give feedback on “old” work over my nights and weekends. So, while it’s not specific to online learning, Jenn’s A Few Ideas for Dealing with Late Work is a post I’ve been trying to put into practice the last few days. I hope this helps!

Graded assignment flexibility is essential to the process of learning in general but especially in our new world of digital divide

It is difficult to determine who is doing the work at home. Follow up videos on seesaw help to see if the student has gained the knowledge or is being given the answers.

This is some good information. This is a difficult subject.

I love the idea of a catch-up cafe! I think I will try to implement this in my school. It’s in the same place every day, yes? And the teachers take turns monitoring? I’m just trying to get a handle on the logistics – I know those will be the first questions I get.

I really enjoyed this post. I think it provides a lot of perspective on a topic that teachers get way too strict about. I just wonder: wouldn’t it be inevitable for students to become lazy and care less about their understanding if there wasn’t any homework (or even if it was optional)? I know students don’t like it, and it can get redundant if they understand the content, but it truly is good practice.

Hi Shannon,

Glad the post helped! Homework is one of those hot educational topics, but I can’t say I’ve personally come across a situation or found any research where kids become lazy or unmotivated if not assigned homework. In fact, research indicates that homework doesn’t really have much impact on learning until high school. I just think that if homework is going to be assigned, it needs to be intentional and purposeful. (If students have already mastered a skill, I’m not sure how homework would provide them much benefit.) Here’s an article that I think is worth checking out. See what you think.

I like how you brought up how homework needs to be given with the understanding that not all kids have the same resources at home. Some kids don’t have computers or their parents won’t let them use it. There is no way of knowing this so teachers should give homework that requires barely any utensils or technology.

I think having students help determine the due dates for major assignments is a great idea. This works well with online schools too. Remote jobs are the future so helping students learn how to set their own due dates and to get homework done from home will prepare them for the future.

This year I am trying something new. After reading this article, I noticed that I have used a combination of some of these strategies to combat late work and encourage students to turn work in on time. I only record a letter grade in the grade book: A, B, C, D, F. If a student turns in an assignment late, I flag it as late, but it does not affect their “grade”.

If a student wants to redo an assignment, they must turn something in. If they miss the due date, they can still turn it in, but lose the opportunity to redo the assignment. Students will meet with me one last time before they turn it in to get final feedback.

At the end of the grading period, I conference with the student about their final grade, looking at how many times they have handed work in on-time or late. This will determine if the student has earned an A or an A+ .

I really appreciate how your post incorporates a lot of suggestions for the way that teachers can think about and grade homework. Thank you for mentioning how different students have different resources available as well. As teachers, we need to be aware of the different resources our students have and tailor our approach to homework to match. I like the idea of grading homework based on completion and accepting late work for full credit at any time (substituting a zero in the grade book until it is turned in). This is definitely a strategy that I’ll be using!

So glad the article was helpful for you! I will be sure to pass on your comments to Jenn.

I also have been teaching for a long time and I have found that providing an END OF WEEK (Friday at 11:59) due date for assignments allows students to get the work completed by that time. It helps with athletes, and others involved in extra curricular activities. I feel this is fair. I give my tests/quizzes on the days assigned and the supplemental work on Fridays.

I personally, as a special education teach, would allow my SPED students extra time to complete the work they have missed. This is in alignment with their IEP accommodations. I would work with each one independently and have remediation with the content that they are having difficulty. This setting would be in a small group and separate classroom.

I really like the idea of a work habits grade. I struggle with students who turn things in late regularly earning the same grade as those who always turn things in on time. A work habits grade could really motivate some learners.

I’ve been in education for 37 years and in all manner of positions. I share this only to also say that things have changed quite a bit. When I started teaching I only had one, maybe two students in a class of 34 elementary students that would not have homework or classwork finished. Now, I have two classes of about 15 each. One group is often half the class on a regular basis not having homework or not finishing classwork on a regular basis- so far. Additionally parents will pull students out to go to amusement parks, etc and expect all work to be made up and at full credit. I believe that the idea of homework is clearly twofold- to teach accountability and to reengage a learner. Classwork is critical to working with the content and, learning objective. We can all grade various ways; however, at some point, the learner has to step up. Learning is not passive, nor is it all on the teacher. I have been called “mean” because I make students do their work in class, refocusing them, etc. I find that is my duty. Late work should be simply dealt with consistently and with understanding to circumstance IMO. You were out or it was late because mom and dad were upset, ok versus we went to Disney for three days and I was too tired. hmm- used to be easy with excused/unexcused absences, now there is no difference. Late with no absence? That can be a problem and I reach out to home and handle it individually at my level.