- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

Pico iyer's 'the half known life' upends the conventional travel genre.

A mesmerizing collection of essays that vividly recalls sojourns to mostly contentious yet fabled realms, Pico Iyer's The Half Known Life upends the conventional travel genre by offering a paradoxical investigation of paradise.

Iyer's deeply reflective explorations at once affirm and challenge the French philosopher Blaise Pascal's statement that "All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone."

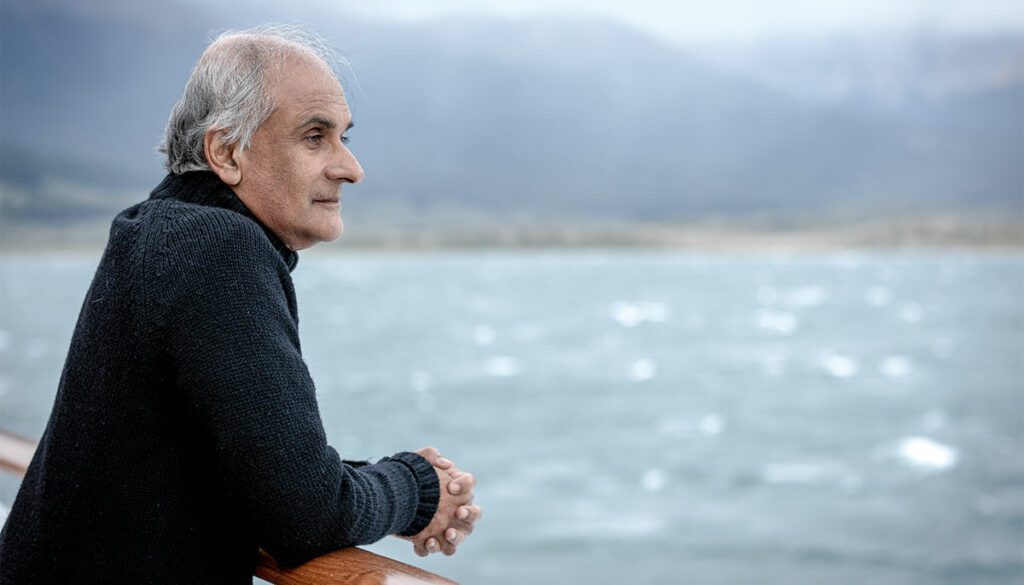

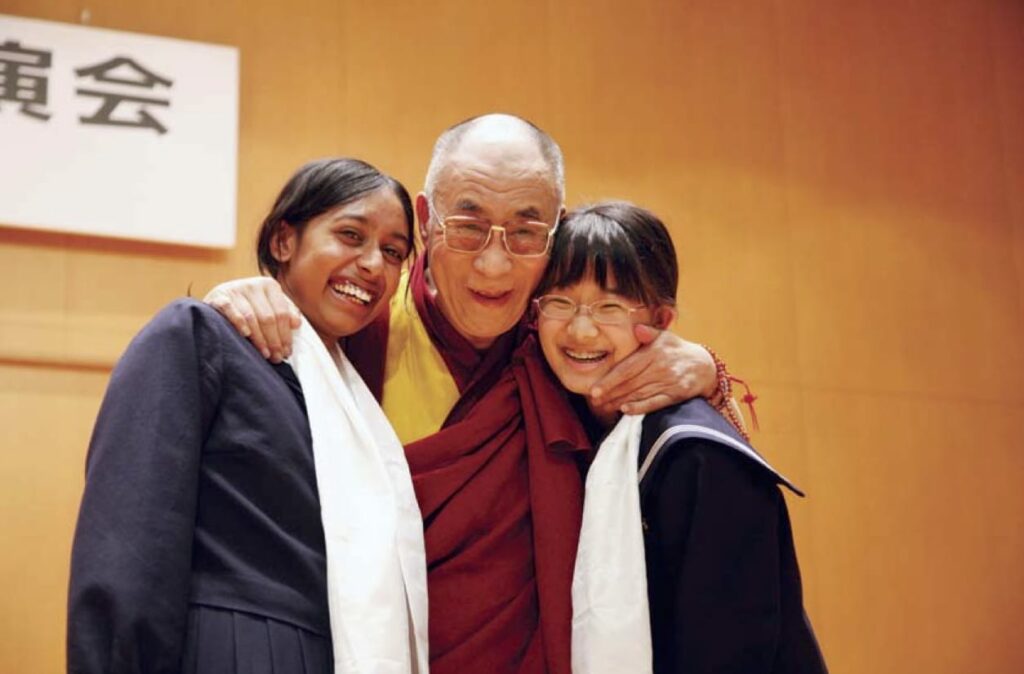

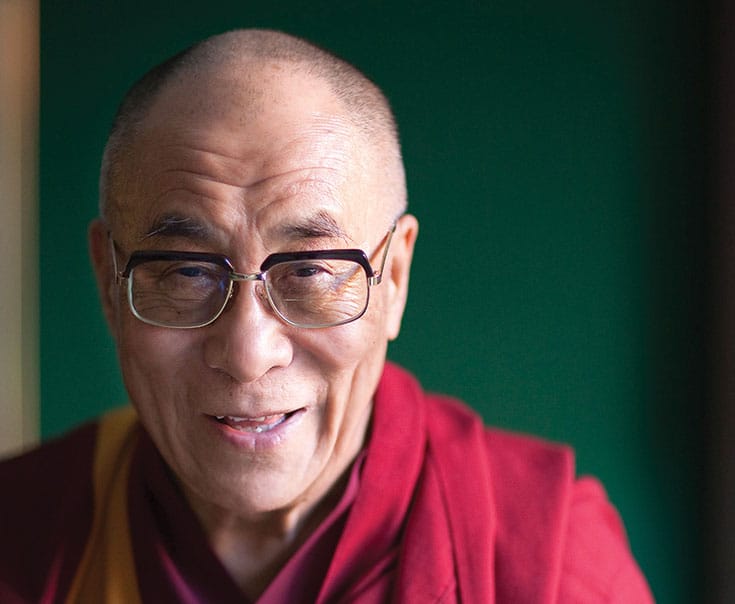

After years of traversing the globe as the Dalai Lama's biographer and observing first-hand how people struggle with the search for a meaningful existence, Iyer, a noted British-American essayist of Tamil ancestry, has often wondered what kind of paradise can be found in our increasingly fractious world.

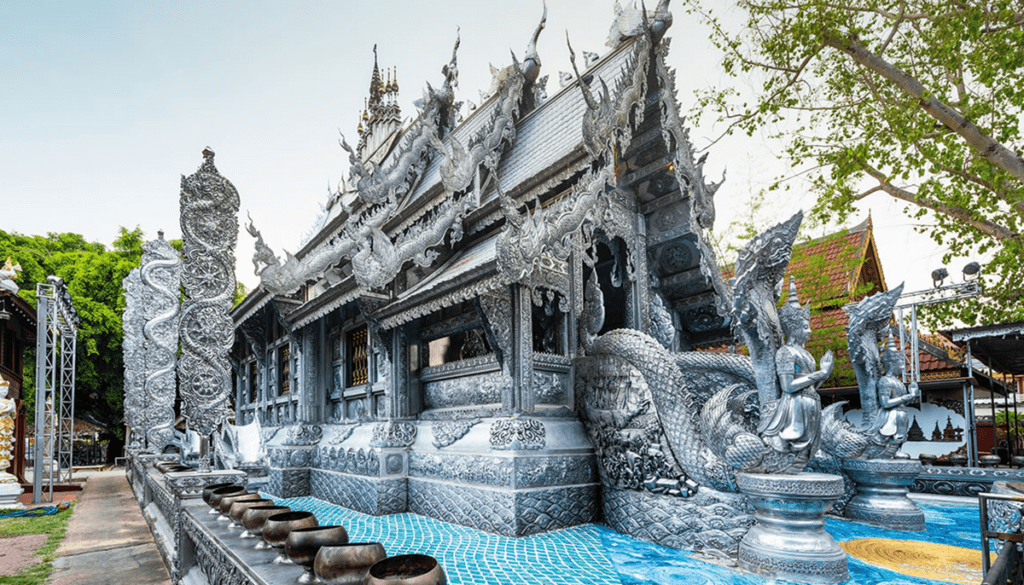

Since travel is often tied to escape/refuge as well as conquest/acquisition, the notion of paradise in today's context inevitably brings up attendant issues of loss, instability, violence and oppression. Voyaging from shadowy mosques and gardens of Iran (where the same Farsi word is used for both "garden" and "paradise") to the sterile skyline of North Korea; the deceptively peaceful lakes of Kashmir to the unyielding terrains of Ladakh and the tense sunlit lawns of Sri Lanka; the wrathful Old Testament landscape of Broome, Australia to the fog-shrouded, Bardo-like embankments of Varanasi; the clamorous streets of Jerusalem to the hushed temples of Koyasan, Japan, Iyer poetically depicts the otherworldly beauty of these places while trenchantly examining the paradox of utopia. Why do so many seeming paradises rupture in suffering and chaos? Is the serpent an inherent feature of paradise? In the process he also questions our idea of knowledge by positing that "the half known life is where so many of our possibilities lie."

While acknowledging that a flawed understanding of other cultures can create tragic consequences, Iyer believes "it's everything half known, from love to faith to wonder and terror," that actually guides the trajectory of one's life. Accordingly, there is usually a gap between our preconceived notion of happiness and a deeper, realer truth that we may intuit but tend to overlook in our pursuit of happiness. "The places we avoid [are] often closer to us than the ones we eagerly seek out," Iyer insightfully observes.

The notion of home/truth versus exile/illusion is fluid one — Iyer is less interested in binary thinking than in embracing contradictions. In his view, it's precisely our imperfect grasp of reality that both invites us to commune with other worlds and teaches us to be humble when we find ourselves untethered from the familiar. Therefore Iyer's idea of paradise, in embracing both engagement and conscious solitude, affirms yet also modifies Pascal's isolationist sentiment. In some way Iyer's worldview is closer to Olga Tokarczuk's Boschian universe of provisionary heretics in The Books of Jacob , and shares more kinship with limbo or hell than what we normally envision as the kingdom of perfect happiness.

In acknowledging suffering as an indispensable feature of paradise, Iyer emphatically renounces a pristine image of Eden, as embodied by North Korea's "massive stage set, all Legoland skyscrapers and false fronts." Seeing the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden as a necessary fall, and the Buddha's departure from his princely estate as a conscious acceptance of human frailties, Iyer concludes that a true paradise is only attainable through displacement.

While The Half Known Land is not without its romantic seductions — Iyer's indelible prose often conjures the hypnotic, teeming vista of a David Lean epic or the evocative interior of a Mira Nair picture — his descriptions are suffused with an awareness of loss. Although we are deeply enchanted by Iyer's recounting of his mother's fairytale childhood in Kashmir's alpine hills, we also understand his wish to relinquish this illusory past:

"Could [my mother's] memories of Kashmir still be found? Should they? The very British who had raised her and educated her so beautifully had also cut the honeymooners' valley into pieces and left it in the hands of implacable [Pakistan, Indian and Chinese] rivals ...."

In another bittersweet story about Kashmir, a Westerner's dream of escape turns into a long lasting, sustainable engagement with the region after the man suffered a devastating loss. In Iyer's riveting anecdotes, a sudden intimacy with death brings one closer to glimpses of paradise. This unflinching yet organic acceptance of death seems to nullify any hubristic attempt toward absolutes. Iyer's discussion of the Dalai Lama's pragmatism in treating various religious traditions as complementary medical systems — rather than mystical truths — seems especially apt. By concentrating on relieving human suffering, His Holiness's teachings are situated in the here and now, rather than in any theoretical exaltation of eternal life.

Finally, The Half Known Life offers us a revelatory refresher on American literature. Iyer's intimations of mortality help us embrace Herman Melville's visceral terror of the unknown in Moby Dick , and his engagement of diverse worlds brings to mind both Emily Dickinson's dwelling in possibility ("The spreading wide my narrow Hands / To gather Paradise") and Elizabeth Bishop's ambiguous epiphany in "Questions of Travel":

"Continent, city, country, society: the choice is never wide and never free."

Thúy Đinh is a freelance critic and literary translator. Her work can be found at thuydinhwriter.com. She tweets @ThuyTBDinh

Pico Iyer Journeys

News >

Explore related articles, new writings.

- Short Films

- Upcoming Events

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (April 2024)

“How Far Would you Travel for Happiness?”–A rich conversation with Marianna Pogosyan for her Psychology Today blog, posted November 8, 2023. “Our constant search for Paradise”—a long interview with the TED Radio Hour, broadcast on November 10, 2023 A long and rich e-mail conversation with Caryl Phillips, on migration and exile, in The Palgrave Handbook […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (October 2023)

An hour-long interview with Doug Fabrizio for Radio West on KUER, April 6, 2023. A long talk with the wonderful editor Melvin McLeod for the Lion’s Roar podcast, April 17, 2023, excerpted in the July/August edition of Lion’s Roar. “The Man from Everywhere”—a short essay to introduce the latest book of photography from Basil Pao, […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (April 2023)

“The Vedanta Temple: Our Second, Deeper Home”—a short essay for the Santa Barbara Independent, October 15, 2022 “A Man of Parts”–a review of A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carre, for Air Mail, December 3, 2022 A discussion of le Carre, on “Monday Meeting,” the Air Mail podcast, December 5, 2022 My annual […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (November 2022)

Around Deer’s Slope”–an essay on walking for the book Where My Feet Fall, published by William Collins in Britain and excerpted in Orion, as “Never the Same River Twice,” March 16, 2022 “At a Loss”–an essay on Juzo Itami’s film The Funeral, for a new Criterion Collection DVD and Blu-Ray released on May 17, 2022, […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (March 2022)

“On Travel-Writing”—an interview with Rick Steves, broadcast on public radio stations across the U.S. on November 7, 2021 “The Future of Hope”—a conversation with Elizabeth Gilbert broadcast for the “On Being” show and podcast on public radio stations across the U.S. on November 18, 2021 “Navigating the Poles”—an Opinion piece on traveling between Japan and […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (October 2021)

“A Scientist of Sorrow”–a review of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun for Air-Mail, February 27, 2021 “All That We Can’t Leave Behind”—an essay on the photographs of Robert Voit, to accompany the exhibition “Aequilibrium” in Berlin, March, 2021. An imaginative essay on “Why I Write” and a long interview on writing for the inaugural […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (February 2021)

“Chi ha dimenticato vuole transcinarci in un mondo di muri”–An interview with La Repubblica on the 75th anniversary of the dropping of a bomb on Hiroshima—August 6, 2020 “The Best Reason to Go to College”—an Op-Ed on the beginning of the new school year, for The New York Times, September 7, 2020 “The Power of […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (July 2020)

“Beneath Us, Beyond Us, Inside Us”—a long introductory essay to the book Masks, by National Geographic photographer Chris Rainier, October 2019 “The Shock of the Old”—an essay on the Naoshima project for the Benesse Art Site Naoshima newsletter, October 2019 “Relative Values”–an essay on Japan and its different relation to reality, for the Times Literary […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (October 2019)

“Japan still inhabits its own ancestral universe”–An essay on Japan for TIME magazine, April 22, 2019 “With New Emperor, Japan Enters the Era of `Joyful Harmony’ “—An Op-Ed on the ascent of a new Emperor in Japan, World Post, Berggruen Institute—April 26, 2019 “The beautiful art-filled Japanese islands left behind by the modern world”—An essay […]

Some Recent Pieces of Iyer (April 2019)

“A Land Apart”—a short essay on why Japan is the Destination of 2019, in Travel & Leisure, December 2018. “Home, Sweet, Temporary Home”—an essay on Tenzing Dakpa’s series of photographs, “The Hotel,” for Aperture magazine, Winter 2018. “The Reel World”—a short essay on seeing movies around the world for Airbnb Magazine, January 2019. “In the […]

The nowhere man

By the time I was nine, I was already used to going to school by transatlantic plane, to sleeping in airports, to shuttling back and forth, three times a year, between my parents' Indian home in California and my boarding school in England. While I was growing up, I was never within 6,000 miles of the nearest relative-and came, therefore, to learn how to define relations in non-familial ways. From the time I was a teenager, I took it for granted that I could take my budget vacations (as I did) in Bolivia and Tibet, China and Morocco. It never seemed strange to me that a girlfriend might be half a world (or ten hours flying time) away, that my closest friends might be on the other side of a continent or sea.

It was only recently that I realised that all these habits of mind and life would scarcely have been imaginable in my parents' youth; that the very facts and facilities that shape my world are all distinctly new developments, and mark me as a modern type.

It was only recently, in fact, that I realised that I am an example, perhaps, of an entirely new breed of people, a transcontinental tribe of wanderers that is multiplying as fast as international telephone lines and frequent flyer programmes. We are the transit loungers, forever heading to the departure gate. We buy our interests duty-free, we eat our food on plastic plates, we watch the world through borrowed headphones. We pass through countries as through revolving doors, resident aliens of the world, impermanent residents of nowhere. Nothing is strange to us, and nowhere is foreign. We are visitors even in our own homes.

This is not, I think, a function of affluence so much as of simple circumstance. I am not, that is, a jet-setter pursuing vacations from Marbella to Phuket; I am a product of a movable sensibility, living and working in a world that is itself increasingly small and increasingly mongrel. I am a multinational soul on a multicultural globe where more and more countries are as polyglot and restless as airports. Taking planes seems as natural to me as picking up the phone, or going to school; I fold up my self and carry it round with me as if it were an overnight case.

The modern world seems increasingly made for people like me. I can plop myself down anywhere and find myself in the same relation of familiarity and strangeness: Lusaka is scarcely more strange to me than the foreigners' England in which I was born, the America where I am registered as an "alien," and the almost unvisited India that people tell me is my home. I can fly from London to San Francisco to Osaka and feel myself no more a foreigner in one place than another; all of them are just locations-pavilions in some intercontinental Expo-and I can work or live or love in any of them. All have Holiday Inns, direct-dial phones, CNN and DHL. All have sushi, Thai restaurants and Kentucky Fried Chicken. My office is as close as the nearest fax machine or modem. Roppongi is West Hollywood is Leblon.

This kind of life offers an unprecedented sense of freedom and mobility: tied down nowhere, we can pick and choose among locations. Ours is the first generation that can go off to visit Tibet for a week, or meet Tibetans down the street; ours is the first generation to be able to go to Nigeria for a holiday to find our roots-or to find that they are not there. At a superficial level, this new internationalism means that I can meet, in the Hilton coffee shop, an Indonesian businessman who is as conversant as I am with Magic Johnson and Madonna. At a deeper level, it means that I need never feel estranged. If all the world is alien to us, all the world is home.

I have learned to love foreignness. In any place I visit, I have the privileges of an outsider: I am an object of interest, and even fascination; I am a person set apart, able to enjoy the benefits of the place without paying the taxes. And the places themselves seem glamorous to me-romantic-as seen through foreign eyes: distance on both sides lends enchantment. Policemen let me off speeding tickets, girls want to hear the story of my life, pedestrians will gladly point me to the nearest golden arches. Perpetual foreigners in the transit lounge, we enjoy a kind of diplomatic immunity; and, living off room service in our hotel rooms, we are never obliged to grow up, or even, really, to be ourselves.

Thus many of us learn to exult in the blessing of belonging to what feels like a whole new race. It is a race, as Salman Rushdie says, of "people who root themselves in ideas rather than places, in memories as much as in material things; people who have been obliged to define themselves-because they are so defined by others-by their otherness; people in whose deepest selves strange fusions occur, unprecedented unions between what they were and where they find themselves." And when people argue that our very notion of wonder is eroded, that alienness itself is as seriously endangered as the wilderness, that more and more of the world is turning into a single synthetic monoculture, I am not worried: a Japanese version of a French fashion is something new, I say, not quite Japanese and not truly French. Comme des Gar?ons hybrids are the art form of the time.

And yet, sometimes, I stop myself and think. What kind of heart is being produced by these new changes? Must I always be a None of the Above? When the stewardess presents me with disembarkation forms, what do I fill in? My passport says one thing, my face another; my accent contradicts my eyes. Place of residence, final destination, even marital status are not much easier to fill in; usually I just tick "other."

Beneath all the boxes, where do we place ourselves? How does one fix a moving object on a map? I am not an exile, really, nor an immigrant; not deracinated, I think, any more than I am rooted. I have not felt the oppression of war, nor found ostracism in the places where I do alight; I scarcely feel severed from a home I have scarcely known. Yet is "citizen of the world" enough to comfort me?

Alienation, we are taught from kindergarten onwards, is the condition of our time. This is the century of exiles and refugees, of boat people and statelessness; the time when traditions have been abolished, and men become closer to machines. This is the century of estrangement: more than a third of all Afghans live outside Afghanistan; the second city of the Khmers is a refugee camp; the second tongue of Beverly Hills is Farsi.

To understand the modern state, we are often told, we must read VS Naipaul, and see how people estranged from their cultures mimic people estranged from their roots. Naipaul is the definitive modern traveller in part because he is the definitive symbol of modern rootlessness; his singular qualification for his wandering is not his stamina, nor his bravado, nor his love of exploration-it is his congenital displacement. Here is a man who was a foreigner at birth, a citizen of an exiled community set down on a colo-nised island. Here is a man for whom every arrival is enigmatic, a man without a home-except for an India to which he stubbornly returns, only to be reminded of his distance from it. The strength of Naipaul is the poignancy of Naipaul: the poignancy of a wanderer who tries to go home, but is not taken in, and is accepted by another home only so long as he admits that he is a lodger there.

There is, however, another way of apprehending foreignness, and that is the way of Nabokov. In him we see an avid cultivation of novelty: he collects foreign worlds with a connoisseur's delight, he sees foreign words as toys to play with, and exile as the state of kings. This touring aristocrat can even relish the pleasures of low culture precisely because they are the things that his own high culture lacks: the motel and the summer camp, the roadside attraction and the hot fudge sundae. I recognise in Nabokov a European's love for the US rooted in the US's very youthfulness and heedlessness; I recognise in him the sense that the newcomer's viewpoint may be the one most conducive to bright ardour. Unfamiliarity, in any form, breeds content.

Nabokov shows us that if nowhere is home, everywhere is. That instead of taking alienation as our natural state, we can feel partially adjusted everywhere. That the outsider at the feast does not have to sit in the corner alone, taking notes; he can plunge into the pleasures of his new home with abandon.

We airport hoppers can, in fact, go through the world as through a house of wonders, picking up something at every stop, and taking the whole globe as our playpen. And we can mix and match as the situation demands. "Nobody's history is my history," Kazuo Ishiguro, a great spokesman for the privileged homeless, once said to me, and then went on, "Whenever it was convenient for me to become very Japanese, I could become very Japanese, and then, when I wanted to drop it, I would just become this ordinary Englishman." Instantly, I felt a shock of recognition: I have a wardrobe of selves from which to choose. And I savour the luxury of being able to be an Indian in Cuba (where people are starving for yoga and Rabindranath Tagore), an American in Thailand; or an Englishman in New York.

And so we go on circling the world, six miles above the ground, displaced from time, above the clouds, with all our needs attended to. We listen to announcements in three languages. We disembark at airports that are self-sufficient communities, with hotels, gymnasia and places of worship. At customs we have nothing to declare but ourselves.

But what price do we pay for all this? I sometimes think that this mobile way of life is as disquietingly novel as high-rises, or the video monitors that are re-wiring our consciousness. Even as we fret about the changes our progress wreaks in the air and on the airwaves, in forests and on streets, we hardly worry about the changes it is working in ourselves, the new kind of soul that is being born out of a new kind of life. Yet this could be the most dangerous development of all, and the least examined.

For us in the transit lounge, disorientation is as alien as affiliation. We become professional observers, able to see the merits and deficiencies of anywhere, to balance our parents' viewpoints with their enemies' position. Yes, we say, of course it's terrible, but look at the situation from Saddam's point of view. I understand how you feel, but the Chinese had their own cultural reasons for Tiananmen Square. Fervour comes to seem to us the most foreign place of all.

Seasoned experts at dispassion, we are less good at involvement, or suspensions of disbelief; at, in fact, the abolition of distance. We are masters of the aerial perspective, but touching down becomes more difficult. Unable to get stirred by the raising of a flag, we are sometimes unable to see how anyone could be stirred. I sometimes think that this is how Rushdie, the great analyst of this condition, somehow became its victim. He had juggled homes for so long, so adroitly, that he forgot how the world looks to someone who is rooted-in country or belief. He had chosen to live so far from affiliation that he could no longer see why people choose affiliation in the first place. Besides, being part of no society means one is accountable to no one, and need respect no laws outside one's own. If single nation people can be fanatical as terrorists, we can end up ineffectual as peace keepers.

We become, in fact, strangers to belief itself, unable to comprehend many of the rages and dogmas that animate (and unite) people. Conflict itself seems inexplicable to us, simply because partisanship is; we have the agnostic's inability to retrace the steps of faith. I could not begin to fathom why some Muslims would think of murder after hearing about The Satanic Verses: yet sometimes I force myself to recall that it is we, in our floating scepticism, who are the exceptions, that in China or Iran, in Korea or Peru, it is not so strange to give up one's life for a cause.

We end up, then, a little like non-aligned nations, confirming our reservations at every step. We tell ourselves, self-servingly, that nationalism breeds monsters, and choose to ignore the fact that internationalism breeds them too. Ours is the culpability not of the assassin, but of the bystander who takes a snapshot of the murder. Or, when the revolution catches fire, hops on the next plane out.

In any case, the issues, in the transit lounge, are passing; a few hours from now, they will be a thousand miles away. Besides, this is a foreign country, we have no interests here. The only thing we have to fear are hijackers-passionate people with beliefs.

Sometimes, though, just sometimes, I am brought up short by symptoms of my condition. I have never bought a house of any kind, and my ideal domestic environment, I sometimes tell my friends, is a hotel room. I have never voted, or ever wanted to vote, and I eat in restaurants three times a day. I have never supported a nation (in the Olympic games, say) or represented "my country" in anything. Even my name is weirdly international, because my "real name" is one that makes sense only in the home where I have never lived.

I choose to live in the US in part because it feels more alien the longer I stay there. I love being in Japan because it reminds me, at every turn, of my foreignness. When I want to see if any place is home, I must subject the candidates to a battery of tests. Home is the place of which one has memories but no expectations.

If I have any deeper home, it is, I suppose, in English. My language is the house I carry around with me as a snail his shell; and in my lesser moments I try to forget that mine is not the language spoken in America, or even, really, by any member of my family.

Yet even here, I find, I cannot place my accent, or reproduce it as I can the tones of others. And I am so used to modifying my English inflections according to whom I am talking to-an American, an Englishman, a villager in Nepal, a receptionist in Paris-that I scarcely know what kind of voice I have.

I wonder, sometimes, if this new kind of non-affiliation may not be alien to something fundamental in the human state. The refugee at least harbours passionate feelings about the world he has left-and generally seeks to return there; the exile at least is propelled by some kind of strong emotion away from the old country and towards the new-indifference is not an exile emotion. But what does the transit lounger feel? What are the issues that we would die for? What are the passions that we would live for?

Airports are among the only sites in public life where emotions are hugely sanctioned, in block capitals. We see people weep, shout, kiss in airports; we see them at the furthest edges of excitement and exhaustion. Airports are privileged spaces where we can see the primal states writ large-fear, recognition, hope. But there are some of us, perhaps, sitting at the departure gate, boarding passes in hand, who feel neither the pain of separation nor the exultation of wonder; who alight with the same emotions with which we embarked; who go down to the baggage carousel and watch our lives circling, circling, circling, waiting to be claimed.

THE TEN GREATEST ESSAYS, EVER

Alas, with essays I could probably choose a hundred old favorites, or a different every hour of the day. But on this particular blazing autumn morning in Japan, the sun burning down out of a cloudless blue sky onto the rusting reds and oranges and lemon-yellows of my local park, the ones that come to me instantly include:

“Self-Reliance,” by Ralph Waldo Emerson (from Essays: First Series , 1841)

“Walking” by Henry David Thoreau (from a lecture, 1861)

“Total Eclipse” by Annie Dillard (from Teaching a Stone to Talk , 1982)

“Late Victorians” by Richard Rodriguez (from Harper’s , October 1990)

“Speaking in Tongues” by Zadie Smith (from The New York Review of Books , February 2009)

“On Going a Journey” by William Hazlitt (from The New Monthly Magazine , 1822)

“The Critic as Artist” by Oscar Wilde (from Intentions , 1891)

“Mrs Gupta Never Rang” by Jan Morris (from City Improbable , 2005)

The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory by Derek Walcott (published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1993)

“Reflections on Writing” by Henry Miller (from Wisdom of the Heart , 1942)

(With sincerest apologies to Donald Richie, Joan Didion, Somerset Maugham, James Wood, Thomas Merton, S.J. Perelman, Norman Mailer, Joseph Brodsky, Virginia Woolf, Woody Allen, Kenneth Tynan, Hunter Thompson, Thomas de Quincey and many others, any one of whom I would probably include in this list if you asked me again an hour from now.)

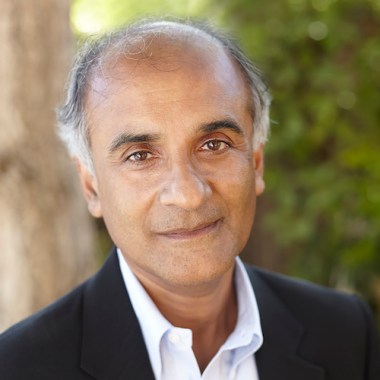

About Pico Iyer

Pico Iyer is one of the world’s foremost travel writers. The author of over ten books, including the seminal Video Night in Katmandu: And Other Reports from the Not-So Far East , Tropical Classical: Essays from Several Directions , and Falling Off the Map: Some Lonely Places of the World . He was named by The Utne Reader one of the world’s “100 Visionaries Who Could Change Your Life” and The New Yorker has said that “As a guide to far flung places, Iyer can hardly be surpassed. His essays regularly appear in Harper’s, The New York Review of Books, National Geographic, Time, The Times Literary Supplement, and many others. He lives in suburban Japan.

- Current Winner

- Past Winners

- Current Nominees

- Past Nominees

- The 10 Great Essays

- Writing, Research & Publishing Guides

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

Tropical Classical: Essays from Several Directions Paperback – June 30, 1998

- Print length 336 pages

- Language English

- Publication date June 30, 1998

- Dimensions 5.19 x 0.76 x 8 inches

- ISBN-10 9780679776109

- ISBN-13 978-0679776109

- See all details

Products related to this item

Editorial Reviews

From the inside flap, from the back cover, about the author, product details.

- ASIN : 0679776109

- Publisher : Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group; First Vintage. edition (June 30, 1998)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 336 pages

- ISBN-10 : 9780679776109

- ISBN-13 : 978-0679776109

- Item Weight : 9.8 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.19 x 0.76 x 8 inches

- #3,024 in Travel Writing Reference

- #4,976 in Travelogues & Travel Essays

- #16,825 in Short Stories Anthologies

About the authors

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Pico Iyer was born in Oxford, England--to parents from India--raised in California and educated at Eton, Oxford and Harvard. Since 1987 he has been based in Western Japan, while traveling everywhere from Bhutan to Easter Island, North Korea to Los Angeles Airport. Apart from the two novels and ten works of non-fiction he has published, he has written the introductions to more than fifty other books, as well as screenplays, librettos and many liner-notes for Leonard Cohen. He speaks regularly everywhere from West Point to Davos and Shanghai to Bogota and between 2013 and 2016, he delivered three talks for TED.com

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 85% 8% 0% 0% 8% 85%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 85% 8% 0% 0% 8% 8%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 85% 8% 0% 0% 8% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 85% 8% 0% 0% 8% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 85% 8% 0% 0% 8% 8%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Advertisement

Supported by

Voices Inside Their Heads

- Share full article

By Pico Iyer

- April 11, 2013

Mohsin Hamid’s latest novel boasts a startlingly distinctive voice, as commanding and unadorned as its title, “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia.” But what may be most exciting about that voice — the whole book is delivered in the terse declarations of a mock self-help manual — is that it’s nothing like the voices we met in his two earlier novels. The first, “Moth Smoke,” was a moody, multipart evocation of party kids and S.U.V.’s in Lahore, poetically given life by Hamid as if to the manner born; his second, “The Reluctant Fundamentalist,” was a fast-moving monologue from a young Pakistani, educated at Princeton and once well employed in New York (as Hamid was), who’s returned to his homeland post-9/11 and lures a Daniel Pearl-like American into a confrontation.

Hamid clearly has a voice, but it’s really a collection of voices; the tension in his work comes from the way he brings one side of himself (the Western-educated and the globally shrewd) against the other (the Pakistani). It’s as if he’s picked up different selves — competing perspectives — at every step along life’s way, so that sometimes the British resident in him surveys his native Pakistan; sometimes the Pakistani in him regards the Ivy League as it could be seen only from afar. Pick up one of his novels, and you never know what voice you’ll encounter.

Writing teachers across the land still urge students, “Find your voice”; publishers are notoriously eager to discover any new writer with as engaging and exceptional a voice as, say, Alice Munro or (the wonderfully mongrel, as it happens) Junot Díaz. But Hamid ushers us into a contemporary world in which, for many, to settle on any one voice is a lie, a betrayal of all the other voices inside us that are equally authentic. As Zadie Smith suggests in her brilliant essay “Speaking in Tongues,” a Barack Obama can speak to black folks in a church and to a Harvard Law School class in entirely different accents, and yet still be himself on both occasions. The burden of being many-voiced is that any style you choose fails to do justice to the many other positions you could take; the blessing is that you can be wise to yourself, as Smith so obviously is, repudiating her previous novels with each new offering. Her extraordinary collection of essays is, perfectly, titled “Changing My Mind.”

To some extent this is true of all of us. Look at your out-box: in the past hour you may have sent e-mails to mother, partner, boss and child, possibly even describing the same party. But each one is likely to have been written in a very different voice, and even to have treated the event quite differently — not to do so would be a form of insensitivity. “A man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him,” as William James had it. It’s the man who doesn’t change his voice according to his audience who seems scary, locked inside his own assumptions.

At its core, writing is about cutting beneath every social expectation to get to the voice you have when no one is listening. It’s about finding something true, the voice that lies beneath all words. But the paradox of writing is that everyone at her desk finds that the stunning passage written in the morning seems flat three hours later, and by the time it’s rewritten, the original version will look dazzling again. Our moods, our beings are as changeable as the sky (long hours at any writing project teach us), so we can no longer trust any one voice as definitive or lasting.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Peeking into Pico Iyer’s Perspectives

Like an ivory frontispiece to a magniloquent tome, wherein lay the annals of a nation splayed across its vellum pages, stood the Raffles Hotel, monumentalising old-world resplendence and modern mystique in its grand visage. Stark against the Singapore sun and sky stood its frosty white marble pillars and alabaster walls, chilled by both its grandeur and the modern air-conditioning.

Sweating from the heat and the imposing event ahead, we students approached, with caution, unsure of where amidst these colonnades, balustrades and quadrangles we would find our session with internationally acclaimed travel writer Pico Iyer, author of The Man Within My Head (2012), Sun After Dark (2004) and The Lady and the Monk (1991). This exclusive engagement on 14 August 2019 for National University of Singapore (NUS) literature students arose on occasion of Mr Iyer becoming the first Writer-in-Residence in the new Raffles Writer’s Residency fellowship, set up by the Raffles Hotel. For the joint organisation and coordination of this opportunity, Associate Professor Anne Thell and the Raffles Hotel receive our sincerest thanks!

We eventually found the venue for the session: Jubilee Lounge. This in turn found us jubilant at our arrival in time – and, mutually, the hotel staff equally jubilant at their successful wrangling of a dishevelled group of students through the labyrinthine hotel and into this immaculate room. Thence began the magic of the moment, manifest by the man of the moment: Mr Iyer opened—with characteristic courtesy, asking leave of the audience to read a passage from his notable work, The Global Soul (2000)—with a reading of a quasi-autobiographical scene of his burning house set ablaze by California forest fires and his harrowing escape.

With a meditative coda, Mr Iyer’s tone dispossessed itself from that different time and turned with warmth to us, instead. With his eyes gleaming with learning and reflection, and his smile—genial, assured and knowing—he invited us into conversation on the notion of home, initiating this topic with intellectual and spiritual verve as he expounded on Buddha’s Fire Sermon, in which the image of a burning house features most prominently as a symbol for the stripping away of the pleasure and perspective of visual indulgence for one to bear witness to the truth. Indeed, for Mr Iyer, a cosmopolitan supra-cityscape like Singapore—with its global connections, globalist orientations and sparse land space—was conducive for the making a global, mobile people who would be especially prepared to take their sense of home with them wherever they went, rather than tether ‘home’ to an expression of a thing or a place.

What constitutes home—for us, for anyone? Our responses were too varied to capture in this brief essay, but I will offer a skeletal report: One English Literature major alumnus, Ong Lin Kang, proffered the observation that the mobility of a people whose homes could be ensouled and so carried with them despite their travels had to be supported by a certain status and privilege. Given this, the increasingly vociferous reactions and sentiments of xenophobia, especially with respect to immigration, could be seen as a conflict between those who sense of home is physical and those for whom it is not physical. Mr. Iyer averred and supplemented this idea—and this in turn prompted Augustine Chay, a current postgraduate student, to ask about Mr Iyer’s views on the ethics of representation in the craft of a literary practitioner of travel writing, as to whether one should take pains to reorient unconscious biases to one’s conscious values. Showing utmost respect to the audience, Mr Iyer asked leave to answer the question posed, in another way. He related his own complex cultural programming: American by residence; British by birth; Indian by ethnicity, citizenry and ancestry; and Japanese by residence and through marriage. Only with an exceptional exercise of self-awareness and self-abnegation could he identify how one or another cultural lens contributed to his perspective – the perspective through which he views the subjects of which he writes, and with which he narrates his views to readers through his work. More often than not, however, it would be a nigh-impossible task. The question then was for readers to identify, and then de-orient themselves from, the writer’s unconscious biases, in relation to the reader’s conscious values. This was why he stood by the words he said in an interview in 2006 that “imaginative imperialism when writing about the West’s meeting with the East […] never concerned [him] too much” – not because it did not concern him at all, but because there was little, if anything at all, that he could do to operationalise that concern. How he could do anything about it, however, would occur in his teaching: guiding others towards developing a critical literary intelligence and independence to do the work of reading with relish, responsibility and resistance.

On the matter of how a writer operationalised his craft, Owen David Harry, another postgraduate student in English Literature, was interested in what Mr Iyer’s actual writing practices were. Mr Iyer was glad to divulge his experience – and revealed that of the questions students had prepared for this session, he was looking forward the most to attempting an answer to this one. He informed us that he sets aside a few hours, at least, each morning for writing, by hand, and insists that he continues this practice even if his writing that day does not come to him easily or well, or if he is travelling and in a new time zone. He perseveres in this way because he has realised that when he does so, even if he does not get much writing done on a current project, he produces something , and is better able the next day to discriminate between what was good in style or subject and what was not, and what should be in this work and what might belong in a subsequent work, like the next book or an essay.

Related to this concern of what goes into constructing place and in writing a book about places, a current English Literature undergraduate, Ariane Noelle Vanco, asked if elision in travel writing is a concern, as surely not everything experienced and observed may be accounted for in writing—and, furthermore, not much that is pejorative or unpleasant finds its way into travel writing. Mr Iyer prefaced his answer as both a response to Ariane and a continuation of his response to Owen about his writing practices: in writing Video Night in Kathmandu (1988), he shuttled from one city to the next, from Rangoon to New York to Manila to Hong Kong to Bombay to Beijing to Bali; and from one country to the next, from Thailand to the Philippines to Nepal to India to Burma to China to America. He was young, and traveling eagerly through fast-paced cities, and furiously scribbled down everything, attempting to record, as much as he could, every perceptual observation—sight, sound, smell, touch and taste—as it happened. He found, though, that while this method captured fresh perceptions, it also encouraged only nascent thoughts about them. Later, he changed his methods and began to exercise more discipline and focus. Now, he jots down phrases and fragments, and what creative and descriptive expressions dawned on him about his observations – how sights could be smelt; and how sounds could be touched and felt, for instance. He then writes from memory and carefully selects just a few details to include—the sound of a saxophone on a busy street, for instance. He acknowledges that reconstructing from memory is difficult, especially if you want to make writing come alive. Oftentimes too perceptions once missed cannot be recovered. Thus he returns to his notes to start writing about his impressions, as these allow him to reconstruct, or approximate, that feeling of first perception that is so central to capturing place. If he can still feel those first sensations via his writing, it is more likely a reader can, too—and that is his wish for any reader of any of his works: to feel place. He concluded jocularly that despite this conscious effort to connect with readers, each time he writes a book he strives to write a very different book than the one before, which may not be viewed as a wise marketing strategy since a reader who loves one book might hate the next! Optimistically, though, he hopes that a reader who hated a first book might find himself or herself loving another.

Picking up from Mr Iyer’s initiation of the topic of Video Night in Kathmandu (1988), I asked if he still held the suspicion that every Asian culture and city he encountered was “too deep, too canny or too self-possessed to be turned by passing trade winds from the west”, as he wrote in that book; and if, in the thirty years since its publication, that suspicion had been ossified or overturned. Mr Iyer smiled and said, “Of course.”

“These are grand, old civilisations that you have in Asia,” he continued. “They will not so spurn themselves to become someone else. Look at China and its resurgent ascendance. Look at India and its innovations for an electronic democracy. Look at Japan, and its cultural and aesthetic power. They have reassurance in and respect for who they regard themselves to be – and who they were and who they want to be.” He also mentioned that the underlying identities of cities and countries are not so easily changed; for instance, a city which might appear to have transformed entirely—a new skyline, new streets, new trends—still retains its unique character. Cities you know well are like old friends: recognizable even after years of distance. He concluded that this was much the case with Singapore, too: Singapore, as he writes in his recently published book This Could Be Home: Raffles Hotel and the City of Tomorrow (2019), “belonged to many cultures all at once, but wasn’t entirely hostage to any one of them.”

(Contributed by Loon Kin Yip, Brendan.)

The New York Times

Opinionator | the joy of less.

The Joy of Less

“The beat of my heart has grown deeper, more active, and yet more peaceful, and it is as if I were all the time storing up inner riches…My [life] is one long sequence of inner miracles.” The young Dutchwoman Etty Hillesum wrote that in a Nazi transit camp in 1943, on her way to her death at Auschwitz two months later. Towards the end of his life, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “All I have seen teaches me to trust the creator for all I have not seen,” though by then he had already lost his father when he was 7, his first wife when she was 20 and his first son, aged 5. In Japan, the late 18th-century poet Issa is celebrated for his delighted, almost child-like celebrations of the natural world. Issa saw four children die in infancy, his wife die in childbirth, and his own body partially paralyzed.

In the corporate world, I always knew there was some higher position I could attain, which meant that, like Zeno’s arrow, I was guaranteed never to arrive and always to remain dissatisfied.

I’m not sure I knew the details of all these lives when I was 29, but I did begin to guess that happiness lies less in our circumstances than in what we make of them, in every sense. “There is nothing either good or bad,” I had heard in high school, from Hamlet, “but thinking makes it so.” I had been lucky enough at that point to stumble into the life I might have dreamed of as a boy: a great job writing on world affairs for Time magazine, an apartment (officially at least) on Park Avenue, enough time and money to take vacations in Burma, Morocco, El Salvador. But every time I went to one of those places, I noticed that the people I met there, mired in difficulty and often warfare, seemed to have more energy and even optimism than the friends I’d grown up with in privileged, peaceful Santa Barbara, Calif., many of whom were on their fourth marriages and seeing a therapist every day. Though I knew that poverty certainly didn’t buy happiness, I wasn’t convinced that money did either.

So — as post-1960s cliché decreed — I left my comfortable job and life to live for a year in a temple on the backstreets of Kyoto. My high-minded year lasted all of a week, by which time I’d noticed that the depthless contemplation of the moon and composition of haiku I’d imagined from afar was really more a matter of cleaning, sweeping and then cleaning some more. But today, more than 21 years later, I still live in the vicinity of Kyoto, in a two-room apartment that makes my old monastic cell look almost luxurious by comparison. I have no bicycle, no car, no television I can understand, no media — and the days seem to stretch into eternities, and I can’t think of a single thing I lack.

I’m no Buddhist monk, and I can’t say I’m in love with renunciation in itself, or traveling an hour or more to print out an article I’ve written, or missing out on the N.B.A. Finals. But at some point, I decided that, for me at least, happiness arose out of all I didn’t want or need, not all I did. And it seemed quite useful to take a clear, hard look at what really led to peace of mind or absorption (the closest I’ve come to understanding happiness). Not having a car gives me volumes not to think or worry about, and makes walks around the neighborhood a daily adventure. Lacking a cell phone and high-speed Internet, I have time to play ping-pong every evening, to write long letters to old friends and to go shopping for my sweetheart (or to track down old baubles for two kids who are now out in the world).

When the phone does ring — once a week — I’m thrilled, as I never was when the phone rang in my overcrowded office in Rockefeller Center. And when I return to the United States every three months or so and pick up a newspaper, I find I haven’t missed much at all. While I’ve been rereading P.G. Wodehouse, or “Walden,” the crazily accelerating roller-coaster of the 24/7 news cycle has propelled people up and down and down and up and then left them pretty much where they started. “I call that man rich,” Henry James’s Ralph Touchett observes in “Portrait of a Lady,” “who can satisfy the requirements of his imagination.” Living in the future tense never did that for me.

Perhaps happiness, like peace or passion, comes most when it isn’t pursued.

I certainly wouldn’t recommend my life to most people — and my heart goes out to those who have recently been condemned to a simplicity they never needed or wanted. But I’m not sure how much outward details or accomplishments ever really make us happy deep down. The millionaires I know seem desperate to become multimillionaires, and spend more time with their lawyers and their bankers than with their friends (whose motivations they are no longer sure of). And I remember how, in the corporate world, I always knew there was some higher position I could attain, which meant that, like Zeno’s arrow, I was guaranteed never to arrive and always to remain dissatisfied.

Being self-employed will always make for a precarious life; these days, it is more uncertain than ever, especially since my tools of choice, written words, are coming to seem like accessories to images. Like almost everyone I know, I’ve lost much of my savings in the past few months. I even went through a dress-rehearsal for our enforced austerity when my family home in Santa Barbara burned to the ground some years ago, leaving me with nothing but the toothbrush I bought from an all-night supermarket that night. And yet my two-room apartment in nowhere Japan seems more abundant than the big house that burned down. I have time to read the new John le Carre, while nibbling at sweet tangerines in the sun. When a Sigur Ros album comes out, it fills my days and nights, resplendent. And then it seems that happiness, like peace or passion, comes most freely when it isn’t pursued.

If you’re the kind of person who prefers freedom to security, who feels more comfortable in a small room than a large one and who finds that happiness comes from matching your wants to your needs, then running to stand still isn’t where your joy lies. In New York, a part of me was always somewhere else, thinking of what a simple life in Japan might be like. Now I’m there, I find that I almost never think of Rockefeller Center or Park Avenue at all.

Related reading in this series: “ The Limits of Control ” by Leonard Mlodinow

“ Simplicity at a Price ,” Reader Comments

“ Happy Like God ” by Simon Critchley

“ Beyond the Sea ” by Simon Critchley

Pico Iyer’s most recent book, “The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama,” is just out in paperback.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

hey Pico, beautiful piece:) i really agree on the point u made towards the end. once you have decided on treading an unknown path with full determination, chances are you end up finding that ur decision was correct. even though financially the situation may not be up to the mark, but that mental peace and happiness is second to none:) take care ciao

I loved this article. It sums me up completely. Simplicity is divine. When I was younger I moved from Canada to the United States, in search of action. What I got was stress. I’m older now and living back in Canada, and let me tell you, having health insurance locked in for life rules. Enough said.

My best friend is an english teacher in Korea and lives a life most people ought to envy: no car and no stuff. Just a quiet and spacious apartment, peace and simplicity.

For all you who crave action, wealth and status: have at it.

There are many similarities between Mr Iyer’s way of life and mine. Although not known in the world of journalism and letters as well as Mr Iyer is, I too began a similar odyssey about 14 years ago. I have come to think of this as my quest to “right-size” my lifestyle. I jumped off the editorial executive ladder at a major computer magazine company, a path I had taken after 15 years climbing the management ranks as an editor in the news business. I now make an adequate living with the writing craft. My accomplishments are not as broadly known as Mr Iyer’s, but they satisfy me, and they pay the rent. I happen to split my time in rural Monterey County, California, and as a writer/photographer in residence at a Shinto community outside Kyoto, where I spend several months each year contributing to their English editorial products. I don’t make a great deal of money, but I do make enough to be able to pay through the nose for health insurance and to take care of other basic needs. People seem envious of the flexibility I have. Some remark that it seems like I have already retired. Far from it; I work hard but not excessively. I take each assignment as it comes and am grateful. My life differs in that I have embraced technology, and find that for me it enhances the sense of freedom and flexibility to pursue this simpler life. I’ve learned that technology need not complicate life, but used properly can help with the simplification. The Internet and cell telephony allow me to tackle an occasional writing project for U.S.-clients when I’m living in Japan, for example. Mr Iyer is dead on right in his last paragraph where he sums up freedom versus security. I would only add — as I tell my curious friends — that every decision we make in life has both a price and payoff.

It’s beautiful what simplicity–either forced or voluntary–can teach us about ourselves…about Life.

Somehow, when removed from the things we think we want, with time, we find the things we need. This has always been my favorite part about traveling, the clarity that arrives just after the longing dissipates.

I’m in a boat similar to yours: living in central Nigeria just seven months after I declared that I’d never leave the bourgeois lifestyle of Western Los Angeles. But here I am, trading beautiful (hot) people, cashmere blankets, and “organic food” for beautiful people, a blanket of stars, and organic food.

Life has a funny way of giving us exactly what we need.

Obi Okorougo //theuberman.com

I don’t think it’s about living in Japan especially, I think it’s about leaving behind all those things that tend over time to clutter up our lives – employment, culture, family, friends, mortages, houses, cars, furniture, expectations – in a word, stuff … I ran away to sea with my wife at 30 in a sail boat, had kids in the Pacific Islands, and worked, in the Middle East mostly. Twenty-five years later we returned home and social pressures had receded – parents had died, siblings were distant and old friends had gone their way. We built a house, set up our kids, and enjoyed our own culture again for a few years – the food, wine, concerts, movies, books, new friends – but now stuff is staring to accumulate. It’s time to have a garage sale, rent out the house and go to sea – we kept the sail boat. I would probably sit here, a grumpy old man counting our dwindling savings, but my brave wife will drag me away again and I’ll learn to love it.

It is amazing, money has no correlation with happiness after a certain period. But I would not want to live without money.

There is never an end to needs and our needs are more a reflection of what our friends have and what is expected that we have.

It has become clearer that my needs are very transitionary. I have moved 6 times in the last 10 years and twice across the continent.

When moving across the continent, I have to choose what I can carry, it is far more expensive to ship then to re-purchase. And what is surprising is the number of boxes that go un opened when I move to the next house. I probably do not need them or probably because it is not accepted that I have them.

But still I purchase, hoping, that this time my purchase will bring me value and happiness.

21 years in kyoto and you dont speak the language? I would call that ignorant, and wouldn’t admit to it on line lol

Thank you for this absolutely beautiful essay and I plan to print it out as a reminder/meditation of my own two rooms within a large home and my life quieting down- in fits and starts- to a goal of tranquility.Making peace with the world and self is not an easy task- to be aware of collisions of history and the daily jars of crime and accidents or the frantic insistence of social tasks emptied of meaning- these must be set aside. But one needn’t cross an ocean to find this serenity- I tred a path of Persian carpets between a mistress suite and kitchen like a pilgrim or empress. “The soul selects her own society” – Emily Dickinson

You state your life choices with sobriety and modesty, almost as if they didn’t amount to much more than a quirky personal path. In my view, however, they’re highly charged with relevance and urgency for people in “rich” countries like the US. Conspicuous consumption, material envy, gigantic houses and cars, the willingness to eat, drink, and swallow anything, and so on are symptoms of a grave spiritual disease with terrible consequences for everyone concerned, and your life choices point toward a remedy.

The question is, how can we persuade more people to embark upon such a rewarding and healthy life? Individuals and families would benefit, of course, but if we achieve critical mass, so would communities, societies, and the whole of humanity!

Of course, we all can’t live the Good Life in an Indiana Chateau.

3 months ago I moved from a Park Avenue apartment to Hong Kong, and I share many of the sentiments you experienced in your move to Japan. Last week I caved and had cable installed; this week I am asking myself why. I think the wants and needs of life are in constant battle with eath other, and our role is to balance them so as to create the most comfortable environment for us. But as we tread this path, we must also have our loved ones in mind, which makes our goal of personal balance that much more complicated.

Over the years Pico Iyer’s travel insights aided by his skill in the craft of writing and his ease of language made for fun reading and evoked one’s own memories of exotic adventures. His “the joy of less”, while a welcome and refreshingly more peaceful view of life is devoid of profundity. Several years ago Pico spoke with professional delight at a book signing talk in Bellingham, Washington. There, hoping to meet a wise man, I sensed that this bright writer had an inner weakness and yearning. Now he is apparently stronger and wiser but still his eloquence imprisons him in golden chains. Freedom comes from discipline and one is spiritual and creative only when one is free. Understanding is silent. I wish him well on his journey.

I wonder if Pico Iyer would feel the same if he did not return to the United States “every three months or so”.

To be able to appreciate just being is one of life’s greatest joys.

A lovely article. I lived in Japan for a while too – I also LOVED having very little media I understood: little TV, few films, and virtually no advertising!!!

I do feel it necessary to point out two things:

One does not need to live in a foreign country to find simplicity. (It can, however, make it easier – it’s easier to buck the status quo if you can’t figure out what it is, will never be a “true” member of it, can’t understand it, etc…)

Many, many, people in Japan live like you once did in Manhattan – under A LOT of pressure, underpaid, etc… (I know several Japanese who found their solace in the US! Works both ways, I suppose).

One of my most peaceful experiences was during a three week permaculture course I took in the San Juan Islands. Lived in a tent, primarily vegan diet, wood-fired shower, composting toilets – spent all day surrounded by interesting intelligent people learning, and my free time swimming, reading, and drawing.

It is a truism that what is good for the individual is not good for the group and vice versa. We cannot all opt-out. Ironically, mass consumerism and economies of scale make opting-out less expensive and easier for those that so choose. To each their own, but we also need leaders to run our companies, to run our economies and to lead our nations. We need people who want to work hard. That enjoy a challenge. People who enjoy their work and work towards goals be they better understanding the world in which we live or how to build a better iPod that helps the global community come together and communicate with one another. We need people who are content to sit in a small apartment and reflect on the world in which we live, and we need those that go to the four corners of the globe to make that world possible. As Japan is a net importer of energy and a net exporter of manufactured goods that means many people are essentially needed to support those that are satisfied with less, so long as their basic needs are met. Think about that. Nameste.

Inspiring words, Pico, that you will probably never read – will you really want to upset your tranquility by reading online blather at the bottom of your column?

Anyway, there is a lot to appreciate in your sentiment, and it resonates with this middle-aged child of the (late) ’60s who grew up with BOTH (Jewish-American) middle class striving and laid-back hippie crunchy-granola-ness running at cross purposes.

We came to Israel a decade ago for a life of meaning, but have been more surprised by how we can enjoy a (slightly) less material life than in America. OK, we have a car, but it’s one car and not two. We can leave work to pick up a sick child. We have many friends (unfortunately not us) with one or both parents in the neighborhood and actively involved in their and their kids’ lives in a way that just doesn’t happen in most Jewish-American middle class existence.

Israel is also at a different stage of development (I use that word advisedly) than America. We are still mostly driven by survival needs, and that has positive ideas as well as (very obvious) negative ones. The real values still apply here, more so than we believe are possible in America.

Pico, what you said was not new – as you quoted many others saying similar things, but it is nice to be reminded of it. Continued good wishes for enjoying the simple(r) life…

Lovely essay. Thank you.

Yes, Pico, yes. As long as our dreams are not bad (it is the guilty conscience that denies happiness), we can be bounded in a nutshell and call ourselves the kings of infinite space.

I have always enjoyed Pico Iyer’s writing immensely, and remember in particular a cover story he did for the New York Times magazine several years ago about the psychological and physical effects of constant inter-continental jet travel. This article supplies a powerful counterpoint to that one.

Anthony De Mello’s Awareness was the milestone book in my life. Had to read it about 6 times before I really began to understand and accept I was asleep. Once I woke up my life began to make sense. Now trying to wake up those around me too.

Thank you for this lovely reflection. My wife and I spend the bulk of each year teaching at a university near Kyoto, and I often marvel, as we sit in the tatami room of our three room apartment (luxury!), how content we are with the absolute simplicity of our lives. We have no car and no cell phone, but the teaching fills our lives with creativity and service and inter-generational juice and Kyoto is a magnificent playground. This simple day to day richness fills our lives with a vitality that surpasses understanding.

The tenth of an inch of difference between heaven and hell is accepting things as they are or wishing them to be otherwise.

— Zen

I believe it all…

…except for not thinking about…or missing…Park Ave, Rockefeller Center (Maison du Chocolat!…although there is one in Tokyo), and, of course, the splendors of Central Park (Shakespeare In The Park begins this Wednesday.), PBS, The Met, The Frick, and all the diversity and intricate wonders of my home sweet home, NYC…

…maybe I should Invite Pico and his companion to have dinner over here and gaze out at my midtown view of this fabulous place. Late, we can all stroll over to Maison du Chocolat for the best pistachio ice cream in the world as dessert.

Even as he says, I agree: The Pursuit of What Matters is not about a place but about a state of mind. And that requires the kind of practical life he describes which can be pursued anywhere, and must be attended to everywhere….

What's Next

Autumn Light: Pico Iyer on Finding Beauty in Impermanence and Luminosity in Loss

By maria popova.

Rilke considered winter the season for tending to one’s inner garden . A century after him, Adam Gopnik reverenced the bleakest season as a necessary counterpoint to the electricity of spring , harmonizing the completeness of the world and helping us better appreciate its beauty — without winter, he argued, “we would be playing life with no flats or sharps, on a piano with no black keys.”

What, then, of autumn — that liminal space between beauty and bleakness, foreboding and bittersweet, yet lovely in its own way? Colette, in her meditation on the splendor of autumn and the autumn of life , celebrated it as a beginning rather than a decline. But perhaps it is neither — perhaps, between its falling leaves and fading light, it is not a movement toward gain or loss but an invitation to attentive stillness and absolute presence, reminding us to cherish the beauty of life not despite its perishability but precisely because of it; because the impermanence of things — of seasons and lifetimes and galaxies and loves — is what confers preciousness and sweetness upon them.

So argues Pico Iyer , one of the most soulful and perceptive writers of our time, in Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells ( public library ).

Having spent a long stretch of life in bicultural seasonality, traveling between the California home of his octogenarian mother and the Japanese home he has made with his wife Hiroko, Iyer reflects on what the country of his heart — home to the beautiful philosophy of wabi-sabi — has taught him about the heart’s seasons:

I long to be in Japan in the autumn. For much of the year, my job, reporting on foreign conflicts and globalism on a human scale, forces me out onto the road; and with my mother in her eighties, living alone in the hills of California, I need to be there much of the time, too. But I try each year to be back in Japan for the season of fire and farewells. Cherry blossoms, pretty and frothy as schoolgirls’ giggles, are the face the country likes to present to the world, all pink and white eroticism; but it’s the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic-blue skies that is the place’s secret heart. We cherish things, Japan has always known, precisely because they cannot last; it’s their frailty that adds sweetness to their beauty. In the central literary text of the land, The Tale of Genji , the word for “impermanence” is used more than a thousand times, and bright, amorous Prince Genji is said to be “a handsomer man in sorrow than in happiness.” Beauty, the foremost Jungian in Japan has observed, “is completed only if we accept the fact of death.” Autumn poses the question we all have to live with: How to hold on to the things we love even though we know that we and they are dying. How to see the world as it is, yet find light within that truth.

The sudden death of Iyer’s father-in-law focuses that existential light to a burning beam and pulls him, unseasonably, to Japan in the flaming height of autumn, to the small wooden house where his wife’s parents lived and loved for half a century. With the suprasensory porousness to life that the death of a loved one gives us, Iyer travels across time and space, to another season and another loss in the California wildfires, and writes:

Everything is burning now, though the days have lost little in clarity or warmth. The leaves are scraps of flame, the hills electric with color; as we fall into December, everything is ready to be reduced to ash. From the windows of the health club, I see bonfires sending smoke above the gas stations; I walk up through magic-hour streets and wonder how long these days of gold can last. It still has the capacity to chill me: the memory of the flames tearing through the black hillsides all around as I drove down after forty-five minutes of watching our family home, some years ago, reduced to cinders. Death paying a house call; and then, when the house was rebuilt on its perilous ridge — where my mother sleeps right now — again and again, new fires rising all around it. One time after another, we receive the reverse-911 call telling us we have to leave right now, and we stuff a few valuables in the car, then watch, from downtown, as the sky above our home turns a coughy black, the sun pulsing like an electrified orange in the heavens.

Between terror and transcendence, between epochs and cultures, Iyer locates the common hearth of human experience:

“Everything must burn,” wrote my secret companion Thomas Merton, as he walked around his silent monastery in the dark, on fire watch. “Everything must burn, my monks,” the Buddha said in his “Fire Sermon”; life itself is a burning house, and soon that body you’re holding will be bones, that face that so moves you a grinning skull. The main temple in Nara has burned and come back and burned and come back, three times over the centuries; the imperial compound, covering a sixth of all Kyoto, has had to be rebuilt fourteen times. What do we have to hold on to? Only the certainty that nothing will go according to design; our hopes are newly built wooden houses, sturdy until someone drops a cigarette or match.

He time-travels once again to several years earlier, when his father-in-law had just turned ninety and Japan had just suffered one of the most devastating disasters in recorded history, to wrest from a moment of life beautiful affirmation for Mary Oliver’s Blake- and Whitman-inspired insistence that “all eternity is in the moment” :

I glance at Hiroko’s watch; later this afternoon, I’ll have to drop the aging couple at their home, and take the rented car to Kyoto Station. Then a six-hour trip, via a series of bullet trains, up to a broken little town in Fukushima, where a nuclear plant melted down after the tsunami seven months ago. A war photographer is waiting for me there, and we’re going to talk to some of the workers who are risking their lives to go into the poisoned area to try to repair the plant, and ask them why they’re doing it. How learn to live with what you can never control? For now, though, there’s nowhere to go on the silent mountain, and a boy who’s just turned ninety is surveying the landscape with the rapt eagerness of an Eagle Scout, while his wife of sixty years sings, “We’re so lucky to have a long life!” Hold this moment forever, I tell myself; it may never come again.

Complement Iyer’s exquisite Autumn Light with physicist and poet Alan Lightman on reconciling our yearning for permanence with a universe predicated on constant change , Marcus Aurelius on the key to living with presence while facing our mortality , and Italian artist Alessandro Sanna’s watercolor love letter to seasonality , then revisit Iyer on what Leonard Cohen taught him about the art of stillness .

— Published October 11, 2019 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2019/10/11/autumn-light-pico-iyer/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture philosophy pico iyer, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

- Our Mission

Pico Iyer is the author of fifteen books, most recently Autumn Light and A Beginner’s Guide to Japan, twinned works on living with uncertainty and impermanence.

Recent Articles

How Travel Opens Your Mind and Heart

Travel wakes us up to the world. Three personal stories of transformational travel in Thailand, Ethiopia, and Yemen.

An Interview with Pico Iyer, The Contemplative Traveler

For writer Pico Iyer, travel is a spiritual experience that shakes up our usual certainties and connects us to a richer, vaster world. Iyer talks with editor-in-chief Melvin McLeod about his book, "The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise," and his eclectic contemplative practice.

My Flight from the Real

Pico Iyer thought he would find what is truly real by going off to a monastery, but he was really fleeing it. Dropping his spiritual romaticism, he found it in ordinary life.

Whatever Way the Wind Blows

So-called objective reality, Pico Iyer finds, is as fickle as the weather. Maybe that’s because it’s as much mind as matter.

My Private Cineplex

The writer's job, says Pico Iyer, is to watch his moods and thoughts, as captivating yet passing as the seasons, and decide which are worth sharing.

Truth in Fiction

Pico Iyer loves reading spiritual books, but he’s found just as much good dharma in the books of three favorite novelists.

Leonard Cohen Burns, and We Burn with Him

“God is a fire,” said Nikos Kazantzakis. “He burns and we burn with Him.” Art, passion, and Zen are fires too—burning the self, leaving behind only ashes and essence.

Heart of the Dalai Lama

In this exclusive and heartfelt essay, Pico Iyer reveals the simple human secret that makes the Dalai Lama the most beloved spiritual figure in the world.

An ICU for the Soul

When a friend is dealt a heavy emotional blow, Pico Iyer suggests to her that silence and stillness might be the best medicine.

Pico Iyer on Graham Greene, the Dalai Lama, and “The Man Within My Head”

Pico Iyer's name is likely familiar to you; he's been a frequent contributor to Lion's Roar, writing about the Dalai Lama, music, travel.

Radar of Compassion

Pico Iyer on the Dalai Lama’s unerring ability to home in on those who most need his love.

Love Makes the Difference

The Dalai Lama draws lessons for all of us from his own experience dealing with difficult times. A conversation with Mary Robinson, Pico Iyer.

About a Poem: Pico Iyer on a haiku by Kobayashi Issa

Pico Iyer on a haiku by Kobayashi Issa.

Feeding the Spiritually Hungry

For all their material success, says Pico Iyer, many Japanese feel alienated and spiritually starved. They responded hungrily to the Dalai Lama’s teachings on his recent tour of Japan.

Thanks for the Dance: Pico Iyer considers Leonard Cohen

Pico Iyer considers Leonard Cohen—the ladies’ man, the balladeer, the Zen poet, and the essence of cool with a new love giving voice to his songs of parting and old age.

Why We Travel: A Love Affair with the World

Like falling in love, travel throws us into a state of delight, uncertainty and self-discovery. Like lovers, travelers both give and receive.

Leonard Cohen: Several Lifetimes Already

Over a long and brilliant career, the poet and singer has lived many lives already, from essence of hip to celebrated lover to serious Zen man.

- Foundations for Being Alive Now

- On Being with Krista Tippett

- Poetry Unbound

- Subscribe to The Pause Newsletter

- What Is The On Being Project?

- Support On Being

Image by Mochizuki Kaoru /Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)..

Sacred Spaces Within and Without

March 15, 2015

The famed journalist and chronicler Pico Iyer wrote an essay entitled “Where Silence Is Sacred” that resonates with me to this day. It was a decidedly non-secular approach to a secular topic; how does someone, living in these warp speed, hyper-connected times find spiritual solace?

Iyer talks about the importance of chapels, especially in today’s frenetic world:

“So much of our time is spent running from ourselves, or hiding from the world; a chapel brings us back to the source, in ourselves and in the larger sense of self.”

Chapels allow us a refuge and a place not to disconnect but perhaps to connect with what is most important to us.

He talks about how he left the frenzied world of journalism for a monastery in Kyoto, Japan to learn about silence and “who (he) was when (he) wasn’t thinking about it.” Iyer returned to that monastery time and again over the next several years and also sought out other spiritual refuges.

Like Iyer, I long held an interest in sacred spaces. However, while I was drawn to the most compassionate elements of various faiths, I had a hard time justifying my interest in sacred spaces to myself. In my professional and personal life I spent much of my time thinking about how people could elevate humanity rather than dwelling on divine intervention. I convinced myself that my attraction to certain sacred spaces had more to do with my interest in their architectural and historical significance rather than their religious or spiritual significance.