David Reimer, 38; After Botched Surgery, He Was Raised as a Girl in Gender Experiment

- Copy Link URL Copied!

David Reimer, the Canadian man raised as a girl for most of the first 14 years of his life in a highly touted medical experiment that seemed to resolve the debate over the cultural and biological determinants of gender, has died at 38. He committed suicide May 4 in his hometown of Winnipeg, Canada.

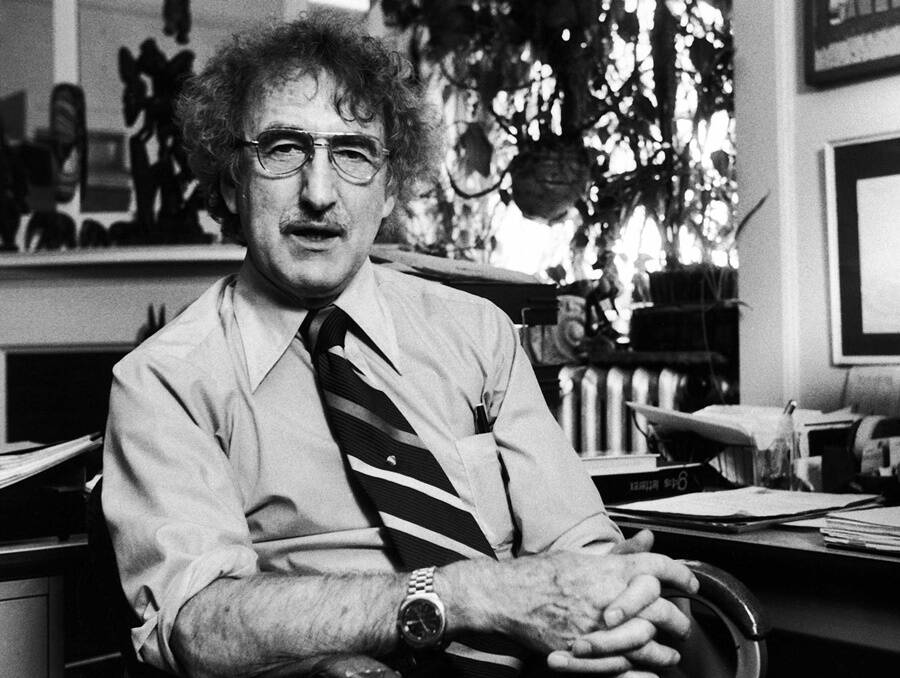

At 8 months of age, Reimer became the unwitting subject of “sex reassignment,” a treatment method embraced by his parents after his penis was all but obliterated during a botched circumcision. The American doctor whose advice they sought recommended that their son be castrated, given hormone treatments and raised as a girl. The physician, Dr. John Money, supervised the case for several years and eventually wrote a paper declaring the success of the gender conversion.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. May 15, 2004 For The Record Los Angeles Times Saturday May 15, 2004 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 0 inches; 25 words Type of Material: Correction Reimer obituary -- The obituary of David Reimer in Thursday’s California section said the doctor who botched Reimer’s circumcision was female. The doctor was male.

Known as the “John/Joan” case, it was widely publicized and gave credence to arguments presented in the 1970s by feminists and others that humans are sexually neutral at birth and that sex roles are largely the product of social conditioning.

But, in fact, the gender conversion was far from successful. Money’s experiment was a disaster for Reimer that created psychological scars he ultimately could not overcome.

Reimer’s story was told in the 2000 book “As Nature Made Him,” by journalist John Colapinto. Reimer said he cooperated with Colapinto in the hope that other children could be spared the miseries he experienced.

Reimer was born on Aug. 22, 1965, 12 minutes before his identical twin brother. His working-class parents named him Bruce and his brother Brian. Both babies were healthy and developed normally until they were seven months old, when they were discovered to have a condition called phimosis, a defect in the foreskin of the penis that makes urination difficult.

The Reimers were told that the problem was easily remedied with circumcision. During the procedure at the hospital, a doctor who did not usually perform such operations was assigned to the Reimer babies. She chose to use an electric cautery machine with a sharp cutting needle to sever the foreskin.

But something went terribly awry. Exactly where the error lay -- in the machine, or in the user -- was never determined. What quickly became clear was that baby Bruce had been irreparably maimed.

(The doctors decided not to try the operation on his brother Brian, whose phimosis later disappeared without treatment.)

The Reimers were distraught. Told that phallic reconstruction was a crude option that would never result in a fully functioning organ, they were without hope until one Sunday evening after the twins’ first birthday when they happened to tune in to an interview with Money on a television talk show. He was describing his successes at Johns Hopkins University in changing the sex of babies born with incomplete or ambiguous genitalia.

He said that through surgeries and hormone treatments he could turn a child into whichever sex seemed most appropriate, and that such reassignments were resulting in happy, healthy children.

Money, a Harvard-educated native of New Zealand, had already established a reputation as one of the world’s leading sex researchers, known for his brilliance and his arrogance. He was credited with coining the term “gender identity” to describe a person’s innate sense of maleness or femaleness.

The Reimers went to see Money, who with unwavering confidence told them that raising Bruce as a girl was the best course, and that they should never say a word to the child about ever having been a boy.

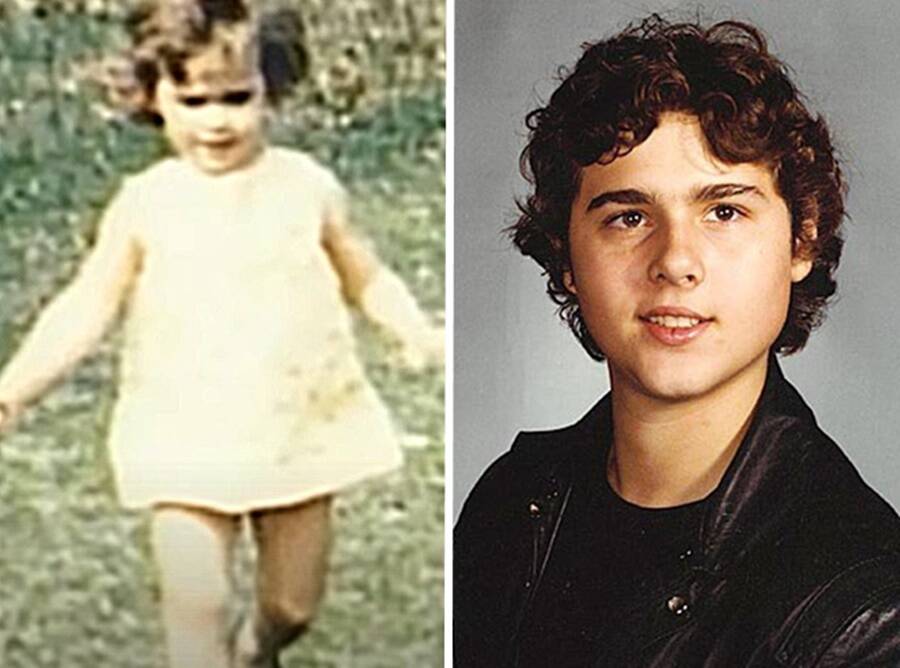

About six weeks before his second birthday, Bruce became Brenda on an operating table at Johns Hopkins. After bringing the toddler home, the Reimers began dressing her like a girl and giving her dolls.

She was, on the surface, an appealing little girl, with round cheeks, curly locks and large, brown eyes. But Brenda rebelled at her imposed identity from the start. She tried to rip off the first dress that her mother sewed for her. When she saw her father shaving, she wanted a razor, too. She favored toy guns and trucks over sewing machines and Barbies. When she fought with her brother, it was clear that she was the stronger of the two. “I recognized Brenda as my sister,” Brian was quoted as saying in the Colapinto book. “But she never, ever acted the part.”

Money continued to perform annual checkups on Brenda, and despite the signs that Brenda was rejecting her feminized self, Money insisted that continuing on the path to womanhood was the proper course for her.

In 1972, when Brenda was 7, Money touted his success with her gender conversion in a speech to the American Assn. for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., and in the book, “Man & Woman, Boy & Girl,” released the same day. The scientists in attendance recognized the significance of the case as readily as Money had years earlier. Because Brenda had an identical male twin, they offered the perfect test of the theory that gender is learned, not inborn.

Money already was the darling of radical feminists such as Kate Millett, who in her bestselling “Sexual Politics” two years earlier had cited Money’s writings from the 1950s as proof that “psychosexual personality is therefore postnatal and learned.”

Now his “success” was written up in Time magazine, which, in reporting on his speech, wrote that Money’s research provided “strong support for a major contention of women’s liberationists: that conventional patterns of masculine and feminine behavior can be altered.” In other words, nurture had trumped nature.

The Reimer case quickly was written into textbooks on pediatrics, psychiatry and sexuality as evidence that anatomy was not destiny, that sexual identity was far more malleable than anyone had thought possible. Money’s claims provided powerful support for those seeking medical or social remedies for gender-based ills.

What went unreported until decades later, however, was that Money’s experiment actually proved the opposite -- the immutability of one’s inborn sense of gender.

Money stopped commenting publicly on the case in 1980 and never acknowledged that the experiment was anything but a glowing success. Dr. Milton Diamond, a sexologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, had long been suspicious of Money’s claims. He was finally able to locate Reimer through a Canadian psychiatrist who had seen Reimer as a patient.

In an article published in the Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine in 1997, Diamond and the psychiatrist, Dr. H. Keith Sigmundson, showed how Brenda had steadily rejected her reassignment from male to female. In early adolescence, she refused to continue receiving the estrogen treatments that had helped her grow breasts. She stopped seeing Money. Finally, at 14, she refused to continue living as a girl.

When she confronted her father, he broke down in tears and told her what had happened shortly after her birth. Instead of being angry, Brenda was relieved. “For the first time everything made sense,” the article by Diamond and Sigmundson quoted her as saying, “and I understood who and what I was.”

She decided to reclaim the identity she was born with by taking male hormone shots and undergoing a double mastectomy and operations to build a penis with skin grafts. She changed her name to David, identifying with the Biblical David who fought Goliath. “It reminded me,” David told Colapinto, “of courage.”

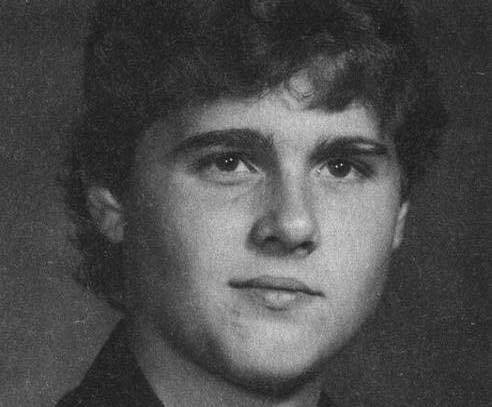

David developed into a muscular, handsome young man. But the grueling surgeries spun him into periods of depression and twice caused him to attempt suicide. He spent months living alone in a cabin in the woods. At 22, he prayed to God for the first time in his life, begging for the chance to be a husband and father.

When he was 25, he married a woman and adopted her three children. Diamond reported that while the phallic reconstruction was only partially successful, David could have sexual intercourse and experience orgasm. He worked in a slaughterhouse and said he was happily adjusted to life as a man.

In interviews for Colapinto’s book, however, he acknowledged a deep well of wrenching anger that would never go away.

“You can never escape the past,” he told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 2000. “I had parts of my body cut away and thrown in a wastepaper basket. I’ve had my mind ripped away.”

His life began to unravel with the suicide of his brother two years ago. Brian Reimer had been treated for schizophrenia and took his life by overdosing on drugs. David visited his brother’s grave every day. He lost his job, separated from his wife and was deeply in debt after a failed investment.

He is survived by his wife, Jane; his parents, and his children.

Despite the hardships he experienced, he said he did not blame his parents for their decision to raise him as a girl. As he told Colapinto, “Mom and Dad wanted this to work so I’d be happy. That’s every parent’s dream for their child. But I couldn’t be happy for my parents. I had to be happy for me. You can’t be something that you’re not. You have to be you.”

Elaine Woo is a Los Angeles native who has written for her hometown paper since 1983. She covered public education and filled a variety of editing assignments before joining “the dead beat” – news obituaries – where she has produced artful pieces on celebrated local, national and international figures, including Norman Mailer, Julia Child and Rosa Parks. She left The Times in 2015.

More From the Los Angeles Times

The new COVID vaccine is here. Why these are the best times to get immunized

Opinion: How bringing back the woolly mammoth could save species that still walk the Earth

Aug. 28, 2024

‘I don’t want him to go’: An autistic teen and his family face stark choices

Aug. 27, 2024

Growing need. Glaring gaps. Why mental health care can be a struggle for autistic youth

David Reimer And The Tragic Story Of The ‘John/Joan Case’

David reimer was born a boy in winnipeg, canada in 1965 — but following a botched circumcision at the age of eight months, his parents raised him as a girl..

Facebook Although David Reimer’s story was initially seen as a success by his family and Dr. John Money, his story would eventually prove to have a tragic end.

David Reimer’s parents just wanted to do the right thing for him.

What was supposed to be a routine circumcision in 1965 turned into a life-altering nightmare for the Reimer family when the doctor performing his surgery accidentally singed the infant’s penis.

The damage was irreparable. Concerned that their son’s injury might cause him mental anguish as an adult, Reimer’s parents consulted with famed sexologist Dr. John Money after seeing him on television.

Money consequently suggested that Reimer undergo sex reassignment surgery and instead be raised female. Desperate, Reimer’s parents took his advice and changed their son’s name from “Bruce” to “Brenda.”

YouTube/Facebook David Reimer, born Bruce Reimer and biologically male, began an imposed gender transition as an infant.

Reimer appeared to take easily to his imposed gender identity as a female, and his case was initially seen as a success story by those physicians like Money who believed that gender was a matter of learned or taught behavior and not nature.

But in reality, Reimer struggled even as a child with his gender identity. Once he discovered the truth about his birth as a teenager, Reimer began a painful journey to return to his biological sex.

However, he could never fully recover. Finally, in 2004, David Reimer took his own life at the age of just 38.

David Reimer’s Future Is Decided By Sexologist John Money

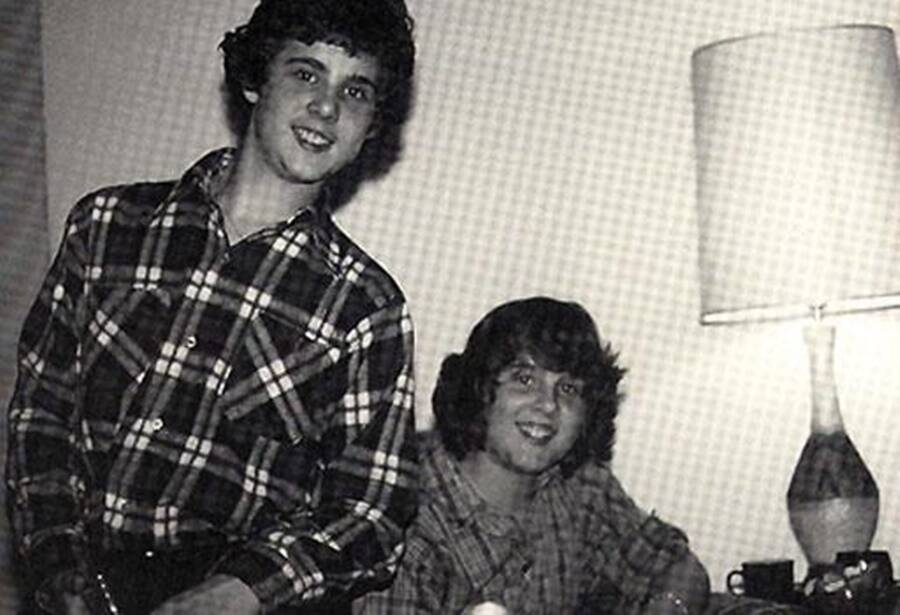

In Memory of David Reimer/Facebook At 14, David Reimer (right) chose to live as a male.

David Reimer was born Bruce Reimer in Winnipeg, Canada, in 1965. He had a twin brother named Brian, and the two were the first children of a rural teenage couple, Janet and Ron.

The baby boys were healthy but, at about eight months old, showed signs of difficulty with urinating. They were diagnosed with phimosis, a condition in which the foreskin cannot retract.

The Reimers took their children to be circumcised at the hospital, but after Bruce Reimer’s surgery went horribly awry because the surgeon used an electrocautery needle instead of a blade, Brian was not subjected to the same surgery and his phimosis healed naturally.

David Reimer’s parents desperately sought solutions for him until they saw psychologist John Money speak about his work on TV.

Money was considered one of the top sex researchers in the United States, and he specialized in the experiences of intersex children who, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies.”

Reimer’s mother wrote to Money explaining the horrible accident her son had endured. Within a few weeks, the young parents were on their way to see the doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

Diana Walker/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images Psychologist John Money claimed his gender experiment on the Reimer twins was a success — despite early warning signs that proved otherwise.

Money believed that a person’s gender identity was a social construct and the result of their upbringing. As such, he proposed that someone could be “taught” to identify differently than their biological sex.

Money thought that children were “gender-neutral” until about the age of two and theorized that parents had a period of time that he called the “gender gate” during which they could influence the sex of their child behaviorally.

The doctor thus made the radical proposition to reassign Bruce Reimer’s gender surgically, which would involve castrating his penis and giving him a prosthetic vagina instead. He would then be raised as a girl and not told of his former identity. Reimer’s parents agreed to the procedure and the infant’s imposed transition began shortly before his second birthday in 1967.

To Money, this situation also provided him with an opportunity to investigate his theory about gender identity. But his medical advice would prove fatally wrong in the case of David Reimer.

Related Posts

Reimer’s troubled childhood and the eventual reveal of the truth.

In Memory of David Reimer/Facebook Despite his tumultuous life, David Reimer found love with his wife Jane.

Upon John Money’s recommendation, Bruce Reimer began life as Brenda Reimer.

In addition to his sex reassignment surgery, Reimer was given estrogen supplements to help “feminize” his body. The Reimers returned to Money’s office every year so that the doctor could monitor both Brian and Brenda’s growth as a boy and a girl. The radical study became known as the John/Joan case.

Money noted that the twin sister, a.k.a. Brenda, was “much neater” than her twin brother Brian. Money also noted that Brenda was the more stubborn and dominant personality, which he dismissed as “tomboy traits.”

In 1975, when the twins turned nine, Money published his study in a book called Sexual Signatures where he described Reimer’s forced transition to Brenda as a success:

“The girl already preferred dresses to pants enjoyed wearing her hair ribbons, bracelets, and frilly blouses, and loved being her daddy’s little sweetheart. Throughout childhood, her stubbornness and the abundant physical energy she shares with her twin brother and expends freely have made her a tomboyish girl, but nonetheless a girl.”

But nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed, Reimer recalled his childhood as far more distressing.

“I never quite fit in,” David Reimer said in a 2000 interview on Oprah . “Building forts and getting into the odd fistfight, climbing trees — that’s the kind of stuff that I liked, but it was unacceptable as a girl.”

According to author John Colapinto who worked with Reimer on his book As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as A Girl , the frequent visits Reimer made to Money’s office were also traumatic.

Reimer was shown pictures of naked adults to “reinforce Brenda’s gender identity” and pressed by Money to endure more surgeries that would make him more feminine. Both of the twins would later accuse Money of making them pose in various sexual positions which, according to Money, was just another element of his theory that involved “sexual rehearsal play.”

Janet Reimer reportedly wasn’t blind to her child’s discomfort with his female gender identity, either. She recalled the first time that Reimer was put in a dress he angrily tore it off. “There were doubts along the way,” Janet confessed on Oprah . “But I couldn’t afford to contemplate them because I couldn’t afford to be wrong.”

Problems at home extended to school. Reimer was teased by classmates for his “masculine gait” and his standing to pee in the girl’s bathroom. When Reimer complained about feeling like a boy, his parents and other adults convinced him that it was just a phase.

Reimer’s secret disrupted the family. His father sunk into alcoholism and his mother attempted suicide. Reimer’s twin sibling, Brian, later descended into substance abuse and petty crime.

It wasn’t until the twins entered their teens that other doctors convinced the Reimers that it was time to tell their children the truth. After picking up Brenda from a psychologist appointment in 1980, Ron Reimer drove both his children to an ice cream parlor where he told them the whole story.

“Suddenly it all made sense why I felt the way I did,” Reimer said of the revelation. “I wasn’t some sort of weirdo. I wasn’t crazy.”

The Tragic End Of David Reimer’s Story

After discovering the truth, Reimer chose to live as a boy and assumed the name “David.”

He endured multiple surgeries to restore his gender to male, including a double mastectomy to remove the breasts that had grown from years of estrogen therapy and attaching an artificial penis in place of his artificial vagina. He also took testosterone supplements.

But the physical stress wore on his mental health. By his early 20s, Reimer had attempted suicide twice and remained deeply depressed for years after.

Despite his anguish, however, Reimer found love and married a woman named Jane. They were together for 14 years. He was a stepfather to her three children and developed hobbies like camping, fishing, antiques, and collecting old coins.

In Memory of David Reimer/Facebook David Reimer took his own life in May 2004. He was 38.

Reimer later agreed to work with a second sexologist named Milton Diamond on the expectation that speaking about his experience might prevent physicians from making similar decisions for other infants.

Diamond criticized Money’s study for its lack of evidence and worked with Reimer to debunk Money’s theory that gender identity could be totally taught or learned. In 1997, around the time Reimer began speaking publicly about his childhood ordeal, Diamond’s study was published in Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine .

The breakthrough paper laid the foundation against performing sex reassignment surgery on intersex infants, which was once considered a “fix” for their gender non-conforming biology.

But the validation of the study wasn’t enough for Reimer to overcome his traumatic childhood. In May 2004, two years after his twin brother succumbed to a drug overdose, David Reimer killed himself. He was 38.

Reimer’s case was complex. His first gender transition was based on a medical accident and a scientific theory. As a result, he experienced gender dysphoria, which is the feeling that one’s biological sex differs from their gender identity. People who identify as transgender often experience gender dysphoria early in life as well.

Reimer may no longer be alive, but his journey to reclaim his gender identity contributed to a better understanding of the relationship between gender and biological sex.

After this look at the story of David Reimer, meet Maryam Khatoon Molkara , the transgender Iranian activist who helped legalize gender-confirming surgeries in Iran. Then, learn about Christine Jorgensen , America’s original transgender celebrity.

PO Box 24091 Brooklyn, NY 11202-4091

John Money Gender Experiment: Reimer Twins

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

The John Money Experiment involved David Reimer, a twin boy raised as a girl following a botched circumcision. Money asserted gender was primarily learned, not innate.

However, David struggled with his female identity and transitioned back to male in adolescence. The case challenged Money’s theory, highlighting the influence of biological sex on gender identity.

- David Reimer was born in 1965; he had a MZ twin brother. When he was 8 months old his penis was accidentally cut off during surgery.

- His parents contacted John Money, a psychologist who was developing a theory of gender neutrality. His theory claimed that a child would take the gender identity he/she was raised with rather than the gender identity corresponding to the biological sex.

- David’s parents brought him up as a girl and Money wrote extensively about this case claiming it supported his theory. However, Brenda as he was named was suffering from severe psychological and emotional difficulties and in her teens, when she found out what had happened, she reverted back to being a boy.

- This case study supports the influence of testosterone on gender development as it shows that David’s brain development was influenced by the presence of this hormone and its effects on gender identity was stronger that the influence of social factors.

What Did John Money Do To The Twins

David Reimer was an identical twin boy born in Canada in 1965. When he was 8 months old, his penis was irreparably damaged during a botched circumcision.

John Money, a psychologist from Johns Hopkins University, had a prominent reputation in the field of sexual development and gender identity.

David’s parents took David to see Dr. Money at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he advised that David be “sex reassigned” as a girl through surgical, hormonal, and psychological treatments.

John Money believed that gender identity is primarily learned through one’s upbringing (nurture) as opposed to one’s inborn traits (nature).

He proposed that gender identity could be changed through behavioral interventions, and he advocated that gender reassignment was the solution for treating any child with intersex traits or atypical sex anatomies.

Dr. John Money argued that it’s possible to habilitate a baby with a defective penis more effectively as a girl than a boy.

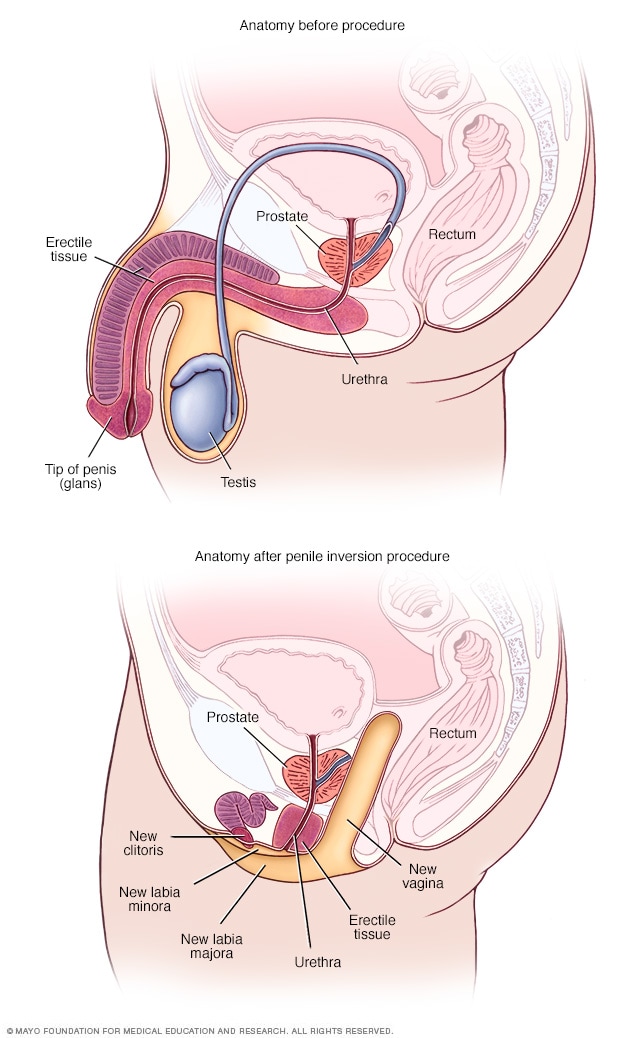

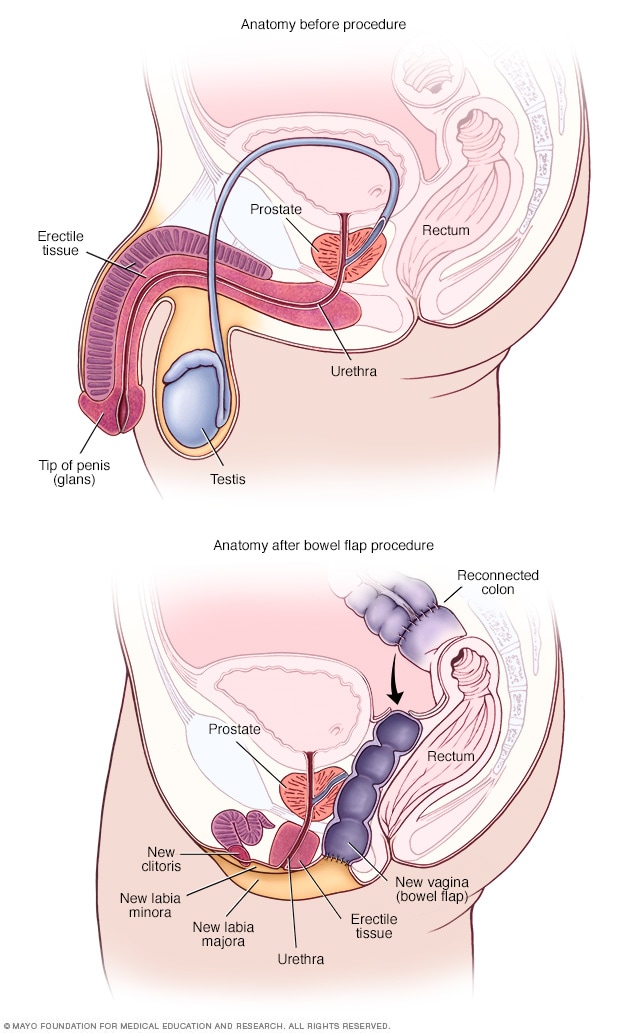

At the age of 22 months, David underwent extensive surgery in which his testes and penis were surgically removed and rudimentary female genitals were constructed.

David’s parents raised him as a female and gave him the name Brenda (this name was chosen to be similar to his birth name, Bruce). David was given estrogen during adolescence to promote the development of breasts.

He was forced to wear dresses and was directed to engage in typical female norms, such as playing with dolls and mingling with other girls.

Throughout his childhood, David was never informed that he was biologically male and that he was an experimental subject in a controversial investigation to bolster Money’s belief in the theory of gender neutrality – that nurture, not nature, determines gender identity and sexual orientation.

David’s twin brother, Brian, served as the ideal control because the brothers had the same genetic makeup, but one was raised as a girl and the other as a boy. Money continued to see David and Brian for consultations and checkups annually.

During these check-ups, Money would force the twins to rehearse sexual acts and inspect one another’s genitals. On some occasions, Money would even photograph the twins doing these exercises. Money claimed that childhood sexual rehearsal play was important for healthy childhood sexual exploration.

David also recalls receiving anger and verbal abuse from Money if they resisted participation.

Money (1972) reported on Reimer’s progress as the “John/Joan case” to keep the identity of David anonymous. Money described David’s transition as successful.

He claimed that David behaved like a little girl and did not demonstrate any of the boyish mannerisms of his twin brother Brian. Money would publish this data to reinforce his theories on gender fluidity and to justify that gender identity is primarily learned.

In reality, though, David was never happy as a girl. He rejected his female identity and experienced severe gender dysphoria . He would complain to his parents and teachers that he felt like a boy and would refuse to wear dresses or play with dolls.

He was severely bullied in school and experienced suicidal depression throughout adolescence. Upon learning about the truth about his birth and sex of rearing from his father at the age of 15, David assumed a male gender identity, calling himself David.

David Reimer underwent treatments to reverse the assignment such as testosterone injections and surgeries to remove his breasts and reconstruct a penis.

David married a woman named Jane at 22 years and adopted three children.

Dr. Milton Diamond, a psychologist and sexologist at the University of Hawaii and a longtime academic rival of John Money, met with David to discuss his story in the mid-1990s.

Diamond (1997) brought David’s experiences to international attention by reporting the true outcome of David’s case to prevent physicians from making similar decisions when treating other infants. Diamond helped debunk Money’s theory that gender identity could be completely learned through intervention.

David continued to suffer from psychological trauma throughout adulthood due to Money’s experiments and his harrowing childhood experiences. David endured unemployment, the death of his twin brother Brian, and marital difficulties.

At the age of thirty-eight, David committed suicide.

David’s case became the subject of multiple books, magazine articles, and documentaries. He brought to attention to the complications of gender identity and called into question the ethicality of sex reassignment of infants and children.

Originally, Money’s view of gender malleability dominated the field as his initial report on David was that the reassignment had been a success. However, this view was disproved once the truth about David came to light.

His case led to a decline in the number of sex reassignment surgeries for unambiguous XY male infants with a micropenis and other congenital malformations and brought into question the malleability of gender and sex.

At present, however, the clinical literature is still deeply divided on the best way to manage cases of intersex infants.

Colapinto, J. (2000). As nature made him: The boy who was raised as a girl. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Colapinto, J. (2018). As nature made him: The boy who was raised as a girl. Langara College.

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, H. K. (1997). Sex reassignment at birth: Long-term review and clinical implications . Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 151(3), 298-304.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Money, J. (1994). The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years . Journal of sex & marital therapy, 20(3), 163-177.

David Reimer and John Money Gender Reassignment Controversy: The John/Joan Case

In the mid-1960s, psychologist John Money encouraged the gender reassignment of David Reimer, who was born a biological male but suffered irreparable damage to his penis as an infant. Born in 1965 as Bruce Reimer, his penis was irreparably damaged during infancy due to a failed circumcision. After encouragement from Money, Reimer’s parents decided to raise Reimer as a girl. Reimer underwent surgery as an infant to construct rudimentary female genitals, and was given female hormones during puberty. During childhood, Reimer was never told he was biologically male and regularly visited Money, who tracked the progress of his gender reassignment. Reimer unknowingly acted as an experimental subject in Money’s controversial investigation, which he called the John/Joan case. The case provided results that were used to justify thousands of sex reassignment surgeries for cases of children with reproductive abnormalities. Despite his upbringing, Reimer rejected the female identity as a young teenager and began living as a male. He suffered severe depression throughout his life, which culminated in his suicide at thirty-eight years old. Reimer, and his public statements about the trauma of his transition, brought attention to gender identity and called into question the sex reassignment of infants and children.

Bruce Peter Reimer was born on 22 August 1965 in Winnipeg, Ontario, to Janet and Ron Reimer. At six months of age, both Reimer and his identical twin, Brian, were diagnosed with phimosis, a condition in which the foreskin of the penis cannot retract, inhibiting regular urination. On 27 April 1966, Reimer underwent circumcision, a common procedure in which a physician surgically removes the foreskin of the penis. Usually, physicians performing circumcisions use a scalpel or other sharp instrument to remove foreskin. However, Reimer’s physician used the unconventional technique of cauterization, or burning to cause tissue death. Reimer’s circumcision failed. Reimer’s brother did not undergo circumcision and his phimosis healed naturally. While the true extent of Reimer’s penile damage was unclear, the overwhelming majority of biographers and journalists maintained that it was either totally severed or otherwise damaged beyond the possibility of function.

In 1967, Reimer’s parents sought the help of John Money, a psychologist and sexologist who worked at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. In the mid-twentieth century, Money helped establish views on the psychology of gender identities and roles. In his academic work, Money argued in favor of the increasingly mainstream idea that gender was a societal construct, malleable from an early age. He stated that being raised as a female was in Reimer’s interest, and recommended sexual reassignment surgery. At the time, infants born with abnormal or intersex genitalia commonly received such interventions.

Following their consultation with Money, Reimer’s parents decided to raise Reimer as a girl. Physicians at the Johns Hopkins Hospital removed Reimer’s testes and damaged penis, and constructed vestigial vulvae and a vaginal canal in their place. The physicians also opened a small hole in Reimer’s lower abdomen for urination. Following his gender reassignment surgery, Reimer was given the first name Brenda, and his parents raised him as a girl. He received estrogen during adolescence to promote the development of breasts. Throughout his childhood, Reimer was not informed about his male biology.

Throughout his childhood, Reimer received annual checkups from Money. His twin brother was also part of Money’s research on sexual development and gender in children. As identical twins growing up in the same family, the Reimer brothers were what Money considered ideal case subjects for a psychology study on gender. Reimer was the first documented case of sex reassignment of a child born developmentally normal, while Reimer’s brother was a control subject who shared Reimer’s genetic makeup, intrauterine space, and household.

During the twin’s psychiatric visits with Money, and as part of his research, Reimer and his twin brother were directed to inspect one another’s genitals and engage in behavior resembling sexual intercourse. Reimer claimed that much of Money’s treatment involved the forced reenactment of sexual positions and motions with his brother. In some exercises, the brothers rehearsed missionary positions with thrusting motions, which Money justified as the rehearsal of healthy childhood sexual exploration. In a Rolling Stone interview, Reimer recalled that at least once, Money photographed those exercises. Money also made the brothers inspect one another’s pubic areas. Reimer stated that Money observed those exercises both alone and with as many as six colleagues. Reimer recounted anger and verbal abuse from Money if he or his brother resisted orders, in contrast to the calm and scientific demeanor Money presented to their parents. Reimer and his brother underwent Money’s treatments at preschool and grade school age. Money described Reimer’s transition as successful, and claimed that Reimer’s girlish behavior stood in stark contrast to his brother’s boyishness. Money reported on Reimer’s case as the John/Joan case, leaving out Reimer’s real name. For over a decade, Reimer and his brother unknowingly provided data that, according to biographers and the Intersex Society of North America, was used to reinforce Money’s theories on gender fluidity and provided justification for thousands of sex reassignment surgeries for children with abnormal genitals.

Contrary to Money’s notes, Reimer reports that as a child he experienced severe gender dysphoria, a condition in which someone experiences distress as a result of their assigned gender. Reimer reported that he did not identify as a girl and resented Money’s visits for treatment. At the age of thirteen, Reimer threatened to commit suicide if his parents took him to Money on the next annual visit. Bullied by peers in school for his masculine traits, Reimer claimed that despite receiving female hormones, wearing dresses, and having his interests directed toward typically female norms, he always felt that he was a boy. In 1980, at the age of fifteen, Reimer’s father told him the truth about his birth and the subsequent procedures. Following that revelation, Reimer assumed a male identity, taking the first name David. By age twenty-one, Reimer had received testosterone therapy and surgeries to remove his breasts and reconstruct a penis. He married Jane Fontaine, a single mother of three, on 22 September 1990.

In adulthood, Reimer reported that he suffered psychological trauma due to Money’s experiments, which Money had used to justify sexual reassignment surgery for children with intersex or damaged genitals since the 1970s. In the mid-1990s, Reimer met Milton Diamond, a psychologist at the University of Hawaii, in Honolulu, Hawaii, and an academic rival of Money. Reimer participated in a follow-up study conducted by Diamond, in which Diamond cataloged the failures of Reimer’s transition.

In 1997, Reimer began speaking publicly about his experiences, beginning with his participation in Diamond’s study. Reimer’s first interview appeared in the December 1997 issue of Rolling Stone magazine. In interviews, and a later book about his experience, Reimer described his interactions with Money as torturous and abusive. Accordingly, Reimer claimed he developed a lifelong distrust of hospitals and medical professionals.

With those reports, Reimer caused a multifaceted controversy over Money’s methods, honesty in data reporting, and the general ethics of sex reassignment surgeries on infants and children. Reimer’s description of his childhood conflicted with the scientific consensus about sex reassignment at the time. According to NOVA , Money led scientists to believe that the John/Joan case demonstrated an unreservedly successful sex transition. Reimer’s parents later blamed Money’s methods and alleged surreptitiousness for the psychological illnesses of their sons, although the notes of a former graduate student in Money’s lab indicated that Reimer’s parents dishonestly represented the transition’s success to Money and his coworkers. Reimer was further alleged by supporters of Money to have incorrectly recalled the details of his treatment. On Reimer’s case, Money publicly dismissed his criticism as anti-feminist and anti-trans bias, but, according to his colleagues, was personally ashamed of the failure.

In his early twenties, Reimer attempted to commit suicide twice. According to Reimer, his adult family life was strained by marital problems and employment difficulty. Reimer’s brother, who suffered from depression and schizophrenia, died from an antidepressant drug overdose in July of 2002. On 2 May 2004, Reimer’s wife told him that she wanted a divorce. Two days later, at the age of thirty-eight, Reimer committed suicide by firearm.

Reimer, Money, and the case became subjects of numerous books and documentaries following the exposé. Reimer also became somewhat iconic in popular culture, being directly referenced or alluded to in the television shows Chicago Hope , Law & Order , and Mental . The BBC series Horizon covered his story in two episodes, “The Boy Who Was Turned into a Girl” (2000) and “Dr. Money and the Boy with No Penis” (2004). Canadian rock group The Weakerthans wrote “Hymn of the Medical Oddity” about Reimer, and the New York-based Ensemble Studio Theatre production Boy was based on Reimer’s life.

- Carey, Benedict. “John William Money, 84, Sexual Identity Researcher, Dies.” New York Times , 11 July 2006.

- Colapinto, John. "The True Story of John/Joan." Rolling Stone 11 (1997): 54–73.

- Colapinto, John. As Nature Made Him: The Boy who was Raised as a Girl . New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000.

- Colapinto, John. "Gender Gap—What were the real reasons behind David Reimer’s suicide?" Slate (2004).

- Dr. Money and the Boy with No Penis , documentary, written by Sanjida O’Connell (BBC, 2004), Film.

- The Boy Who Was Turned Into a Girl , documentary, directed by Andrew Cohen (BBC, 2000.), Film.

- “Who was David Reimer (also, sadly, known as John/Joan)?” Intersex Society of North America . http://www.isna.org/faq/reimer (Accessed October 31, 2017).

How to cite

Articles rights and graphics.

Copyright Arizona Board of Regents Licensed as Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Last modified

Share this page.

'You can't undo surgery': More parents of intersex babies are rejecting operations

Kristina Turner will never forget the moment doctors at a hospital in Washington state told her something was different about her baby. Shortly after Ori was born in 2007, the medical staff noticed that the infant had abnormal genital swelling. Other than that, doctors assured Turner, everything was fine.

“They identified Ori as being female and told us we had a happy, healthy baby, and we went on our way,” Turner told NBC News.

But as a mother, Turner recalled, “I kind of knew something was different.”

A specialist later told Turner, a massage therapist, and her husband, Josh, a construction worker, that their infant had a rare intersex condition called partial androgen insensitivity syndrome with mosaicism. The condition caused Ori to have both XX chromosomes and XY chromosomes and genitalia that doctors did not consider clearly “male” or “female.”

Ori was perfectly healthy, but Turner said surgeons pressured her to agree to cosmetic surgery to make Ori appear more clearly female. She immediately refused.

“Intersex” is an umbrella term for people whose bodies do not match the strict definitions of male or female. Dozens of intersex variations exist, affecting the reproductive organs in ways that may or may not be visible. While the Trump administration seeks to permanently identify people as “male” or “female” based on their physical appearance at birth — a leaked draft proposal was sharply criticized by LGBTQ advocates this week — at least one in 2,000 people are born with atypical genitalia because of one of these conditions, according to Human Rights Watch, an international research and advocacy group.

“Gender normalizing” surgeries have been performed on intersex babies and children since at least the 1950s, often in secrecy, without ever telling the children. In the following decades, some people who underwent these surgeries as children began to speak out against them as human rights violations. Some said they had been assigned the wrong gender, while others had endured severe complications, including sexual dysfunction and infertility.

As their stories piled up, advocacy groups began calling for better education and support for parents of intersex children, as well as for limits on these types of operations. The advocates do not oppose surgery for intersex people in general, but they believe that if the goal is more cosmetic than medical, it’s a choice children should be allowed to make for themselves when they’re older.

This view is gaining traction. Three U.S. surgeons general, the United Nations, the World Health Organization, Physicians for Human Rights, the American Academy of Family Physicians , Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have condemned medically unnecessary surgery on these children. In August, California became the first state to pass a resolution condemning the operations, though they are still legal there.

NBC OUT 'A baby cannot provide ... consent': Calif. lawmakers denounce infant intersex surgeries

But within the medical community — and within support groups for these children — opinion is not unanimous. The Societies for Pediatric Urology, which represents the physicians who treat these patients, strongly disagreed with the California legislation. The organization believes parents should have the option of choosing surgery for their baby if they believe it’s best for the child’s long-term physical and mental health.

In the absence of clear guidance, hundreds of parents in the U.S. each year face a decision that will have a lifelong impact on their child. There are no official figures, but experts believe that while more parents are deciding against surgery, they are still in the minority.

Dr. Yee-Ming Chan, a pediatric endocrinologist at Harvard Medical School, said there is little research to help parents decide.

“There’s certainly stories of individuals who found it distressing to have ambiguous genitalia, but we don’t know how representative that is,” Chan said. “So I think there really is a ton of unanswered questions.”

ORI’S STORY

Turner, who lives an hour and a half north of Seattle, faced criticism from some extended family members who believed she was placing an enormous burden on her newborn in choosing not to have the surgery.

“But I just completely disagreed,” Turner, 35, said, “because I was like, ‘You can’t undo surgery.’”

Since she couldn’t predict the gender her child would embrace, she said, it didn’t seem like her decision to make. And she recalled that none of the doctors could tell her how the surgery, which involved altering sensitive tissue, might affect the baby as an adult.

Based on the advice of medical professionals, Turner and her husband decided to raise Ori as a girl, because they were told that was how the child would likely identify. But the parents always planned to give Ori leeway to explore. If there was a chance that Ori felt male, Turner wanted it to be clear that that was OK. She concocted a bedtime story in which doctors aren’t sure what a baby’s sex is, so the parents let the baby decide over time.

Around the age of 7, Ori came to Turner one night and said, “I feel like I was supposed to be a boy.”

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, thank God I didn’t make a huge mistake,’” Turner said of her decision not to do the surgery.

For several years, Ori wore boy’s clothing and wanted to be called Alex. Then, around fifth grade, Ori started to dress and behave in ways stereotypical of boys and girls — “a cute hair clip with a really masculine outfit,” Turner recalled.

In 2017, the Turners took Ori to a gathering of people who are intersex in Phoenix. There, Ori met some attendees who identified as transgender or nonbinary (neither male nor female). Ori decided to stop using the name Alex and asked to be called by gender-neutral they/them pronouns.

Ori, now 11, loves playing video games like Minecraft and is enamored with the movie franchise “How to Train Your Dragon.” Ori has not been bullied and said that being intersex is “really fun and awesome.”

The middle schooler wants to be a lawyer and an actor someday — as well as an activist “so I can help intersex kids and adults.” In March, Ori gave a TEDx Talk about growing up intersex. Turner helped with the presentation, but the gregarious preteen did most of the talking.

“I wish that [people] knew that intersex people are just like them,” Ori said. “They’re human.”

THE SURGERY QUESTION

In rare cases, intersex babies need emergency surgery when they are born — for example, if they are unable to urinate properly.

But in the vast majority of cases, the operations are done to prevent a child from suffering presumed psychological distress later in life, experts said. Surgeons prefer to do these operations when children are between 6 and 18 months old — when healing is believed to be optimal and when children are too young to remember, experts said.

"It’s a violation of their human rights to choose what they want their bodies to be like."

In these cases, based on assumptions about a child’s future desires, “medically necessary” is hard to define, Chan said.

“Ultimately, my concern is that we find that things like doing some of the surgeries in infancy might be really helpful and beneficial for some individuals, and really harmful for others, and how do you balance that out?” he asked.

Parents often say that their decision to agree to surgery was at least partly driven by fear, according to a 2017 Human Rights Watch report on surgery on intersex children. There’s a growing acceptance among young Americans for those who identify outside the male-female binary — 56 percent of Generation Z kids know someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns, one survey found — and New York City recently joined four states in allowing gender-neutral birth certificates . But amid the Trump administration’s reported push to more stringently define gender identity, parents still worry about bullying, as well as the judgment their child could face in day care centers and locker rooms.

Opponents of surgery say that it is more likely to cause distress than to prevent it. For instance, if a child who undergoes feminizing surgery later identifies as male, “that’s really a catastrophe,” said Dr. Arlene Baratz, a physician and an advocate at interACT, a group that supports intersex youth.

“To do that before children have a say is, I believe it’s a violation of their human rights to choose what they want their bodies to be like,” Baratz said.

THE CASE FOR SURGERY

Because of the variety of intersex conditions and the range of medical advice, some experts fear California’s legislation and other efforts to restrict surgery could have a negative effect on some intersex children.

Dr. Earl Cheng, a surgeon and urologist with H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, called the efforts “a catch-all umbrella in which one size fits all.”

“One size does not fit all,” Cheng said. “You need to have a discussion based upon exactly what that individual has.”

Some adults who underwent the surgery as children say they’re happy with the results.

Lesley Holroyd, 61, a nurse who lives in Florida, was born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), which means she is genetically female but was overexposed to male hormones in utero.

“I’ve had no issues,” Holroyd said of having surgery as a child, adding that the thought of not having done so was “horrifying.” She said she has always seen herself as female and does not identify as intersex.

“Parents know their children certainly better than the government does."

A 2018 study found that 79 percent of adult CAH women who received surgery as children were satisfied with surgical outcomes.

The CARES Foundation, an organization that supports families with children with CAH, lobbied to make them exempt from the California resolution, saying surgery should be up to their parents.

“Parents know their children certainly better than the government does,” said Dina Matos, the group’s executive director.

‘JUST LIKE RAISING ANY OTHER KID’

While adults debate what’s best for kids like Ori Turner, the sixth-grader has already figured it out. Asked about surgery, Ori replied that it was unnecessary because “I’m perfect.”

Ori, who goes to school part time and is home-schooled the rest, is writing a children’s book about growing up as an intersex kid, tentatively titled “The Story of Ori.” The preteen wants Washington State to outlaw cosmetic surgeries on intersex infants and plans to start a petition with interACT.

Turner said parenting an intersex child has been challenging at times, especially when some relatives have criticized her choices, but she said she has learned to “stand strong” in her beliefs.

“Raising Ori is just like raising any other kid,” Turner said. “It’s raising the rest of the world that’s the problem.”

FOLLOW NBC OUT ON TWITTER , FACEBOOK AND INSTAGRAM

- The Moving Image

A Perfect Daughter: Gender Reassignment by Gillian Laub

N ikki was born Niko. A biological boy at birth, she began at the age of 10 the complicated transition to becoming girl. With the utmost support of her family and friends, two years later, she is living happily as the person she always knew herself to be — singing, acting and dancing, often draped in pink.

Earlier this summer, PEOPLE magazine commissioned photographer Gillian Laub to spend several days with Nikki’s family in California, documenting her life after the transition through video and photographic stills. Her portrait shows what it was like for Nikki coming out with her gender identity, finding solace in puberty-blocking medication and looking to the gender reassignment surgery on the horizon for her teenage years.

“It’s always an honor when someone is open and wants to share their life in such an intimate way under the gaze of a camera,” Laub tells TIME, “so the minute the editor told me about Nikki, I said of course I would love to do it.”

To gain their trust and to make them feel comfortable, Laub spent the first day just talking with the family without her cameras.

“Nikki told me she spent the first ten years of her life feeling like she was in the wrong body, almost betrayed by it,” she says. “After the transition, she finally felt happy, safe and proud in her body. I wanted to convey the new feeling of freedom and liberation.”

What stood out to Laub most and what she aimed to capture in the video above was how immensely loving Nikki’s family was. With the knowledge that 50% of transgender youth will attempt to commit suicide by the age of 20, they strove to provide all the support they could for their child to lead the life she wanted.

“Although this story ultimately is a very happy ending,” Laub says, “the family went through years of heartache and stress. They lived with a secret that they all struggled with for very long. The reason they were sharing their story publicly is because they wished they had known sooner that this was actually something many families deal with; they wouldn’t have had so many years of worry and confusion.”

Gillian Laub is a photographer based in New York and a frequent contributor to TIME. See more of her work here .

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik .

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Sex reassignment at birth. Long-term review and clinical implications

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Anatomy and Reproductive Biology, Pacific Center for Sex and Society, University of Hawaii-Manoa, USA.

- PMID: 9080940

- DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170400084015

This article is a long-term follow-up to a classic case reported in pediatric, psychiatric, and sexological literature. The penis of an XY individual was accidentally ablated and he was subsequently raised as a female. Initially this individual was described as developing into a normally functioning female. The individual, however, was later found to reject this sex of rearing, switched at puberty to living as a male, and has successfully lived as such from that time to the present. The standard in instances of extensive penile damage to infants is to recommend rearing the male as a female. Subsequent cases should, however, be managed in light of this new evidence.

PubMed Disclaimer

- To be male or female--that is the question. Reiner W. Reiner W. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997 Mar;151(3):224-5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170400010002. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997. PMID: 9080927 No abstract available.

- Sex reassignment at birth: long-term review and clinical implications. Van Howe RS, Cold CJ. Van Howe RS, et al. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997 Oct;151(10):1062. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170470096021. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997. PMID: 9343024 No abstract available.

- Sex reassignment at birth. Benjamin JT. Benjamin JT. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997 Oct;151(10):1062-4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170470096023. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997. PMID: 9343025 No abstract available.

- Sex reassignment at birth. Schwarz HP. Schwarz HP. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997 Oct;151(10):1064. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170470098026. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997. PMID: 9343026 No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Experiment of nurture: ablatio penis at 2 months, sex reassignment at 7 months, and a psychosexual follow-up in young adulthood. Bradley SJ, Oliver GD, Chernick AB, Zucker KJ. Bradley SJ, et al. Pediatrics. 1998 Jul;102(1):e9. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.e9. Pediatrics. 1998. PMID: 9651461

- Ambiguous genitalia, gender-identity problems, and sex reassignment. Dittmann RW. Dittmann RW. J Sex Marital Ther. 1998 Oct-Dec;24(4):255-71. doi: 10.1080/00926239808403961. J Sex Marital Ther. 1998. PMID: 9805286

- [Gender selection and postoperative follow-up analysis in 85 children with 46, XY disorders of sex development]. Zhao M, Gong CX, Liang AM, Song YN, Liu Y, Wang JL, Ma Y, Ji WJ. Zhao M, et al. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2019 Jun 2;57(6):434-439. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2019.06.007. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2019. PMID: 31216800 Chinese.

- Gender identity outcome in female-raised 46,XY persons with penile agenesis, cloacal exstrophy of the bladder, or penile ablation. Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Arch Sex Behav. 2005 Aug;34(4):423-38. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-4342-9. Arch Sex Behav. 2005. PMID: 16010465 Review.

- Gender identity/role differentiation in adolescents affected by syndromes of abnormal sex differentiation. Wisniewski AB, Migeon CJ. Wisniewski AB, et al. Adolesc Med. 2002 Feb;13(1):119-28, vii. Adolesc Med. 2002. PMID: 11841959 Review.

- Recommendations for 46,XY Disorders/Differences of Sex Development Across Two Decades: Insights from North American Pediatric Endocrinologists and Urologists. Khorashad BS, Gardner M, Lee PA, Kogan BA, Sandberg DE. Khorashad BS, et al. Arch Sex Behav. 2024 Aug;53(8):2939-2956. doi: 10.1007/s10508-024-02942-1. Epub 2024 Jul 22. Arch Sex Behav. 2024. PMID: 39039338 Free PMC article.

- Gender Identity Orientation and Sexual Activity-A Survey among Transgender and Gender-Diverse (TGD) Individuals in Norway. Almås EM, Benestad EEP, Bolstad SH, Karlsen TI, Giami A. Almås EM, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Feb 16;12(4):482. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12040482. Healthcare (Basel). 2024. PMID: 38391857 Free PMC article.

- "I Think It's Too Early to Know": Gender Identity Labels and Gender Expression of Young Children With Nonbinary or Binary Transgender Parents. Riskind RG, Tornello SL. Riskind RG, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Aug 17;13:916088. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.916088. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 36059766 Free PMC article.

- Low Perinatal Androgens Predict Recalled Childhood Gender Nonconformity in Men. Shirazi TN, Self H, Rosenfield KA, Dawood K, Welling LLM, Cárdenas R, Bailey JM, Balasubramanian R, Delaney A, Breedlove SM, Puts DA. Shirazi TN, et al. Psychol Sci. 2022 Mar;33(3):343-353. doi: 10.1177/09567976211036075. Epub 2022 Feb 22. Psychol Sci. 2022. PMID: 35191784 Free PMC article.

- The "Normalization" of Intersex Bodies and "Othering" of Intersex Identities in Australia. Carpenter M. Carpenter M. J Bioeth Inq. 2018 Dec;15(4):487-495. doi: 10.1007/s11673-018-9855-8. Epub 2018 May 7. J Bioeth Inq. 2018. PMID: 29736897

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Silverchair Information Systems

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- GENDER REVOLUTION

In the Operating Room During Gender Reassignment Surgery

Behind the scenes with identical twin Emmie Smith during her medical transition.

Before August 30, 2016, getting stitches at age seven was the most time Emmie Smith had ever spent in a hospital.

That morning, she swapped her plaid shirt and jean shorts for a gown, tucked her hair into a cap, and prepared for surgery to conform her anatomy to the gender she already identified with: woman. In the operating room with her was National Geographic photographer Lynn Johnson. She and Emmie hoped they could demystify the procedure by documenting it, close-up and unflinching. “It was stressful and scary at times, but it almost created a mission other than just recovery,” Emmie says. “We were making something together.”

It had been a year and a half since Emmie had first come out as a transgender woman on Facebook. Telling her family and friends had been an enormous relief. “I’m not sure I could have taken another few years of being closeted,” she says.

Still, it was a challenging time for her family. Her mother, Reverend Kate Malin, is a prominent figure in their Massachusetts town, and her identical twin sons Caleb and Walker were familiar fixtures at her Episcopal church. A month after Walker came out as Emmie, Malin stepped out from behind her pulpit and walked into the aisle. Halfway through her sermon she decided it was time to address the change in her family.

“As most of you know, Bruce and I have three children,” she began. “Caleb and Walker, who are 17, and 13-year-old Owen. Walker’s new name is Emerson, and she prefers Emmie or Em. She’s wearing feminine clothing and makeup and will likely continue to move in the direction of a more feminized body.”

Follow Emmie's transition in pictures

Kate nervously revealed her struggle to the attentive New England crowd. “I feel broken much of the time,” she confessed. “I’ve wanted to run away, and I’ve prayed for this child that I would gladly die for, guilty for how much I miss the person I thought was Walker and everything I thought might be.”

After the sermon, the congregation engulfed her in a hug. Then they moved to offer words of support to the sandy-haired 17-year-old sitting in the pews. In the first of many awkward mistakes the family would later laugh about, it was Caleb—Emmie’s identical twin.

After that sermon, a “new normal” set in. On a Saturday night soon after, they had their first “out” outing. Kate took Emmie—whose hair was still short and chest was flat—to buy a prom dress at David’s Bridal. She feared someone would point or laugh, but the crowds of brides and bridesmaids in the dressing room offered only compliments.

Though she hadn’t initially considered surgery, after a couple of months Emmie had grown frustrated by the tucking and taping required to fit into women’s clothes. That fall, her senior year of high school, she decided to do it.

But waking up after the operation, Emmie felt none of the immediate relief she’d expected. In the recovery room her earbuds played a soothing loop of Bon Iver and Simon and Garfunkel, but it didn’t drown out her disappointment and fear. In retrospect, she thought, hadn’t life before been OK?

It wasn’t until months later, when she was home and could walk and sit again, that Emmie knew she’d made the right choice. “If you’re not living freely that’s time wasted, and I felt my time was wasted pretending to be a boy,” she says. “It was the best decision in my life.”

Now, halfway through a gap year, she’s applying to college theater programs. It’s strange, she says, knowing that her future classmates may watch Johnson’s film and learn the most intimate details of her life. She’s hopeful that her participation will evolve the public’s understanding of gender reassignment surgery. “It’s not science fiction or mythology,” Emmie says. “It’s what happens to women just trying to be at peace with themselves and their bodies.”

Related Topics

You may also like.

Meet the 5 iconic women being honored on new quarters in 2024

Source page for gender identity map.

How science is helping us understand gender

Redefining gender.

Prehistoric female hunter discovery upends gender role assumptions

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Your browser is out-of-date!

Internet Explorer 11 has been retired by Microsoft as of June 15, 2022. To get the best experience on this website, we recommend using a modern browser, such as Safari, Chrome or Edge.

What Is Gender Confirmation Surgery?

Learn about transgender surgery: male-to-female, female-to-male.

Transgender individuals feel that the sex they were assigned at birth, such as male or female, does not match the gender with which they identify. For example, a baby assigned “male” at birth may grow up with a sense of feeling they are female.

As a result of feeling that they were born in the wrong gender, some transgender individuals experience psychological distress known as “ gender dysphoria ” and take various actions to better align their gender identification with their external appearance. For some individuals, the transition process from one gender to another may include medical treatments, such as hormone therapy and gender confirmation surgery.

What is hormone therapy?

Usually the first step in the gender transition process, hormone therapy is intended to suppress the assigned sex characteristics, promote the desired characteristics, or both. For example, men who identify as women may take anti-androgens to block production of the male hormone testosterone, as well as estrogen to appear more feminine. Similarly, women who identify as men may take testosterone to develop more masculine features, such as facial hair.

What is gender confirmation surgery?

If hormone therapy does not have the desired effectiveness, gender confirmation surgery may be an option. Also called gender reassignment surgery, the goal of this procedure is to create the outward physical appearance of the gender with which the person identifies. “Top surgery” refers to surgery above the waist, while “bottom surgery” refers to surgery below the waist.

Transgender surgery is major surgery and generally not considered reversible, so many healthcare providers require transgender individuals to complete several steps before they will proceed with surgery. These may include requiring a formal diagnosis of gender dysphoria and having counseling to determine their psychological readiness for surgery.

“Gender confirmation surgery involves both physical and psychological aspects,” says Manish Champaneria, MD , a plastic surgeon at Scripps Clinic. “Scripps follows the recommendations of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) regarding preparation for surgery, including having a referral from a mental health provider. Patients undergoing surgery are urged to live as the gender they identify as for at least 12 months before having the procedure.”

Gender confirmation surgery options

Scripps offers gender confirmation surgery procedures for both male-to-female (MTF) or transwomen patients, and female-to-male (FTM) or transmen patients.

Top surgery

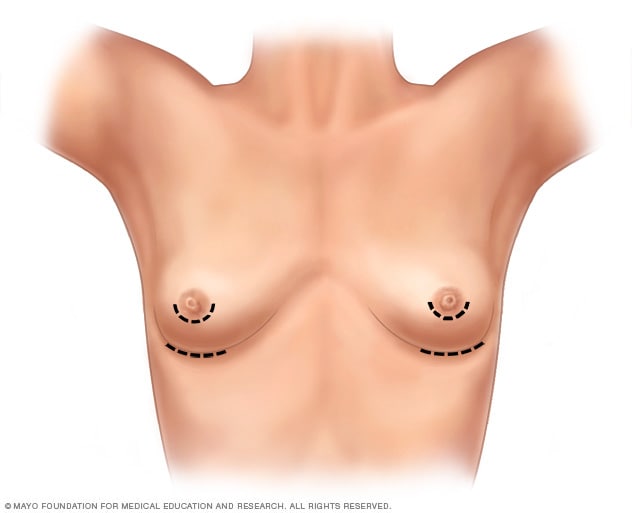

Performed on the chest, top surgery is intended to create a more gender-confirming physique. Top surgery procedures include mastectomies for transmen and breast augmentation for transwomen. In most cases, top surgeries are completed in a single procedure.

MTF top surgery

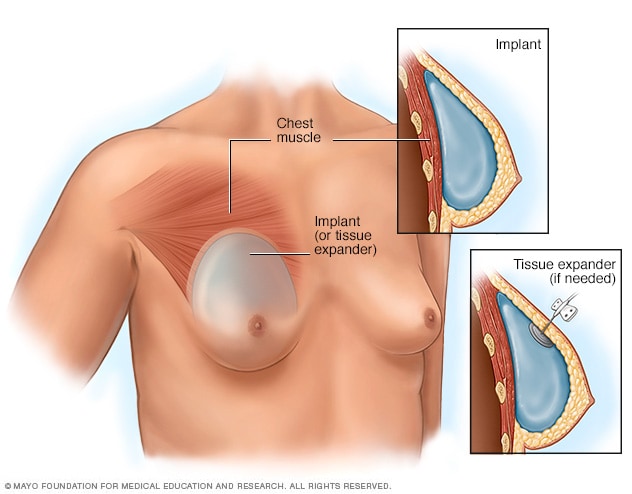

MTF top surgery to augment the breasts may involve fat transfer or breast implants. In a fat transfer procedure, the surgeon removes fat from other parts of the body and injects it into the breasts. Fat transfer may be recommended for patients who wish to increase breast size without breast implants.

Patients who seek larger breasts may choose to have breast implants, which are surgically placed under the chest muscles to enhance breast size and shape. The surgeon and patient together determine the most appropriate size and type of implants.

FTM top surgery

In FTM top surgery, the surgeon removes breast tissue and manipulates the remaining tissue to create a more masculine appearance.

Facial feminization surgery

During MTF facial feminization surgery, the surgeon restructures masculine facial features to achieve a more feminine look. This involves reshaping bones and soft tissues and may be performed as a single procedure or in several stages.

Body contouring

Using various procedures, body contouring reshapes the body to create a more masculine or feminine physique. Specific procedures depend on the patient’s original body shape and desired outcomes. For example, fat transfer may be used to reduce curves in some areas and create them in others.

“We understand that gender confirmation surgery is a life-changing procedure that requires multidisciplinary medical expertise and experience, and we work very closely with our transgender patients every step of the way,” says Dr. Champaneria. “We urge anyone considering this surgery to start by talking with a trusted and physician who is experienced in transgender procedures.”

Related tags:

- Health and Wellness

- Women’s Health

- Men’s Health

The Debate About Sex Assigned at Birth

Accounting for sex in biological research is complicated..

Posted June 29, 2024 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

- There has been a lot of rethinking about how we define biological sex of late.

- Some biological scientists struggle with these changes because of the way studies are traditionally conducted.

- We need a middle path to understand the true nature of sex and gender.

It is becoming increasingly common in many medical and academic circles to stop referring to a person as “male” or “female” and instead refer to their “sex assigned at birth.” The motivation behind this is a welcome desire to understand the needs of transgender and gender-diverse people who are often the victims of discrimination and stigma , which can lead to significant disparities in health care and imperil the health of sexual minority people.

Yet the move away from talking about sex in biological research and medicine may also be problematic in certain circumstances. As discussed in a May 15 article in the journal Nature , “ Neglecting sex and gender in research is a public-health risk ,” there is no question that differences exist between men and women in a variety of health outcomes.

The authors write that three things about sex and gender must be considered in biological research and medical practice: “How sex and gender can have huge effects on health outcomes; how these effects are often disregarded in basic research and clinical trials; and that change can come only through increasing awareness among all stakeholders of the importance” of rethinking how we approach the topics of sex and gender.

Is Sex Assigned at Birth Problematic?

A philosopher, Alex Byrne, and an evolutionary biologist, Carole K. Hooven, recently decried the use of the phrase “sex assigned at birth” in a New York Times op-ed. “Sex is a fundamental biological feature with significant consequences for our species,” they wrote last April, “so there are costs to encouraging misconceptions about it.”

They go on to reiterate the points made in the Nature article, emphasizing that there are unmistakable differences in many aspects of health that are based on an individual’s biological sex, and state that the phrase sex assigned at birth “can also suggest that there is no objective reality behind ‘male’ and ‘female,’ no biological categories to which the words refer.” Byrne and Hooven reject the idea promulgated by philosophers like Michel Foucault and Judith Butler that “sex is somehow a cultural production, the result of labeling babies male and female” and insist that “Sexed organisms were present on Earth at least a billion years ago, and males and females would have been around even if humans never evolved.”

Health Outcomes Differ Between Males and Females

As noted in the Nature article, “For Alzheimer’s [disease] and many other diseases that are common causes of death, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory conditions, and diabetes, a person’s sex and gender can influence their risk of developing the disease, how quickly and accurately they are diagnosed, what treatment they receive and how they fare.”

Note that these authors refer both to sex and gender. Sex is generally conceived of as encompassing the biological differences between males and females, based on genetics and sex hormones , whereas gender includes “the social, psychological, cultural and behavioral aspects of being a man or woman (whether cisgender or transgender), non-binary or identifying with one or more other evolving terms.”

The Nature authors point to a host of differences in the expression of diseases like heart attacks, strokes, and cancer. Examples include that men develop cardiovascular disease earlier than women, women are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than men, cancer chemotherapies work better in women than men and so on—to which we would add that depression and anxiety disorders are more common in women than men.

Some of these may be explained by sociocultural factors. For instance, men are more likely to smoke tobacco than women and this increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and many forms of cancer.

Other differences, however, in disease expression and health outcomes may be due to more clearly biological factors and these are, according to the Nature authors, substantially understudied. “Take the sex of the cell lines that are stored in commercial cell banks,” they point out, “which have been studied for decades and are the source of today’s textbook knowledge.” In many cases, male lines outnumber female lines.

On a clinical level, women are underrepresented in many trials of new therapeutics, leading to a significant lack of knowledge about differences in treatment responses between the sexes. This can have disastrous consequences. “Between 1976 and 2000… eight prescription drugs were retracted from the U.S. market because inadequate clinical testing in women had failed to identify that the drugs put women at greater risk of developing health problems than men.”

The debate about how to talk about sex is clearly heated. On the one hand, there are risks to ignoring biological differences between men and women and to taking the position that sex lacks any objective reality. On the other hand, insisting that everything about sex is biological and determined by genes and hormones ignores the complexities of human psychology and denies the reality of people who do not conform to binary sex categories.

More Nuanced Research Needed

Clearly, a more nuanced approach is necessary. An example of this is research recently reported from the University of Montreal that examined both biological factors and psychosocial factors that determine cognitive differences.

It is known that in general women perform better than men on tests of verbal and fine motor ability, whereas men do better on spatial and mental rotation tasks. The Montreal investigators recruited 222 adults who represented several different subgroups: cisgender heterosexual men, cisgender non-heterosexual men, cisgender heterosexual women, cisgender non-heterosexual women, and gender diverse people. The research study participants were administered a series of cognitive tests, gave saliva samples for measurement of sex hormones, and completed self-report questionnaires about psychosocial variables.

The study found that “biological factors seem to better explain differences in male-typed cognitive tasks (i.e., spatial), while psychosocial factors seem to better explain differences in female-typed cognitive tasks (i.e., verbal).” Hence, sex was associated with cognitive abilities commonly found to be stronger in men than women whereas gender was associated with cognitive abilities commonly found to be stronger in women than men.

Of course, studies like this one need to be replicated before we draw conclusions, but this one represents a welcome accounting of a variety of factors to try to disentangle differences between males and females, some based on biology and others on cultural and psychological factors. Until we have more of this kind of work, we will be left in the dark about the fundamental ways in which men and women differ, making us ignorant of factors with profound influence on the expression and course of many human diseases.

For now, we will continue to use the phrase “sex assigned at birth” because we recognize the importance of the inclusion of people who don’t identify as binary. However, we will also support research aimed at furthering our understanding of the ways the complexity of sex and gender affects human health.

Sara Gorman, PhD, MPH, is a public health specialist, and Jack M. Gorman, MD, is a psychiatrist.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center