An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Plants (Basel)

The Role of Botanical Families in Medicinal Ethnobotany: A Phylogenetic Perspective

1 Institut Botànic de Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-Ajuntament de Barcelona), Passeig del Migdia s.n., Parc de Montjuïc, 08038 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; [email protected] (O.H.); se.cisc.bbi@ejtanragt (T.G.)

Oriane Hidalgo

Ugo d’ambrosio.

2 Mediterranean Ethnobiology Programme Director, Global Diversity Foundation, 37 St. Margarets Street, Canterbury, Kent CT1 2TU, UK; moc.oohay@aipotogu

Montse Parada

3 Laboratori de Botànica (UB)—Unitat associada al CSIC, Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Institut de Recerca de la Biodiversitat—IRBio, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Joan XXIII 27-31, 08028 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; [email protected]

Teresa Garnatje

Joan vallès.

4 Secció de Ciències Biològiques, Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Carrer del Carme 47, 08001 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

Associated Data

The data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Material S2 , and further information could bo obtained on request from the corresponding authors.

Studies suggesting that medicinal plants are not chosen at random are becoming more common. The goal of this work is to shed light on the role of botanical families in ethnobotany, depicting in a molecular phylogenetic frame the relationships between families and medicinal uses of vascular plants in several Catalan-speaking territories. The simple quantitative analyses for ailments categories and the construction of families and disorders matrix were carried out in this study. A Bayesian approach was used to estimate the over- and underused families in the medicinal flora. Phylogenetically informed analyses were carried out to identify lineages in which there is an overrepresentation of families in a given category of use, i.e., hot nodes. The ethnobotanicity index, at a specific level, was calculated and also adapted to the family level. Two diversity indices to measure the richness of reported taxa within each family were calculated. A total of 47,630 use reports were analysed. These uses are grouped in 120 botanical families. The ethnobotanicity index for this area is 14.44% and the ethnobotanicity index at the family level is 68.21%. The most-reported families are Lamiaceae and Asteraceae and the most reported troubles are disorders of the digestive and nutritional system. Based on the meta-analytic results, indicating hot nodes of useful plants at the phylogenetic level, specific ethnopharmacological research may be suggested, including a phytochemical approach of particularly interesting taxa.

1. Introduction

Ethnobotany is a relatively recent denomination for a discipline that studies plant names, uses and management by human societies from ancient to current times, aiming at their projection to the future [ 1 ]. Even if a precedent of this term, botanical ethnography, was coined to name the investigation of any plant materials in archaeology in order to unveil their uses and symbolisms [ 2 ], Harshberger [ 1 ] himself emphasised the fact that ethnobotanical findings should not only constitute an inventory of old knowledge, but should be relevant for current productive activities. From those dates to the present times, ethnobotany undertook methodological innovations, but maintained the double approach of recording and preserving the ancient uses of plants by people—which contributes to describing human lifestyles—and aiming to improve human life conditions [ 3 ]. This is why the collection of plant uses related to health, mostly medicinal and food ones, are predominant in ethnobotanical research, although other uses are relevant as well [ 4 ]. According to the importance of using folk local knowledge to preserve and improve health, not a few drugs have been developed based on their ethnobotanical background, such as, to quote just two famous and recent ones, the oseltamivir, used against chicken flu [ 5 ], and the antimalarial artemisinin [ 6 ]. Additionally, in agreement with this, medical or pharmaceutical ethnobotany, the botanical side of ethnopharmacology, is one of the main pillars of the discipline, particularly in industrialised countries [ 7 , 8 ].

In Europe, the Catalan linguistic domain, the framework of the present research, is among the better-known Iberian areas from an ethnobotanical viewpoint [ 9 ]. The amount of information recollected until now allows us to start conducting research involving comparison among several territories [ 4 , 10 ], in order to establish general patterns in ethnobotanical knowledge.

In the above-referred geographical area, as in general in Europe and worldwide, the predominant ethnobotanical research has been an ethnofloristic one [ 11 , 12 ]. Nevertheless, efforts are being devoted toward finding other complementary approaches, such as studies focused on plants used for ailments related to a determined system, and on the validation of the ethnobotanical evidence with chemical or pharmacological data [ 13 ]. Moreover, the potentially predictive role of molecular phylogeny in bioprospection and in phytochemistry [ 14 , 15 ] and the concept of ethnobotanical convergence [ 16 , 17 ] has opened the way to integrate ethnobotany with genetic (including molecular phylogenetic), genomic (and other “omic” disciplines) and phytochemical approaches [ 18 , 19 ].

One of the aspects always addressed in ethnobotanical investigation is the distribution of the plant taxa recorded in botanical families, since, after the number of plant species known in a given territory, the families in which they are included is one of the most evident pieces of information. Even if some deeper analyses of the causes for some predominating families have been undertaken [ 18 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ], work in this field is still lacking, including territories other than those already considered, and taking into account, among others, phylogenetic issues.

Several statistical methods have been used to test whether a specific taxonomic group is over- or underrepresented in an ethnobotanical flora in comparison to overall local flora. Although the linear regression analysis [ 21 ] and binomial analysis [ 24 ] have been widely used, more recent studies have pointed out some limitations in these previous analytical methods, and propose a Bayesian approach in order to analyse the over- and underused plant groups [ 22 , 23 ]. This method allows us to consider the uncertainty of the proportion of medicinal plant species in the overall flora and shows its robustness in small datasets [ 22 ].

In this context, the aim of this work is to shed light on the role of botanical families in ethnobotany, depicting, in a molecular phylogenetic frame, the relationships between botanical families and medicinal uses of vascular plants in several Catalan-speaking territories (Formentera, Mallorca, and Catalonia, Northern Catalonia included). This will allow us to ascertain the most used families in pharmaceutical ethnobotany in this area and the possible phylogenetic reasons accounting for this, and to find out whether some families are more focused on some particular health conditions than others.

2. Results and Discussion

For the areas under consideration, we analysed a total of 47,630 use reports corresponding to medicinal uses of vascular plants in human medicine registered in our database, including data from ethnobotanical research performed from 1991 until today, in order to study different aspects related to the botanical families to which these uses belong, and the disorders they refer to.

Based on these data, we can state that the medical ethnobotany of the Catalan-speaking territories scrutinised is distributed in 120 botanical families of vascular plants (seven to pteridophytes, five to gymnosperms and 108 to angiosperms). These families include 894 taxa, with medicinal uses, of which 41 have only been determined at generic level (the remaining majority, at specific and infraspecific levels).

The ethnobotanicity index (EI) for the studied area is 14.44%. In addition, the total considered flora ([ 25 ], see materials and methods for precisions) is at least slightly larger than that of the territories object of the present research, since some plants present in the places not covered here (i.e., Valencian area and some of the Balearic Islands) do not grow in the areas here concerned. This just means that, in fact, the EI in the studied area has been slightly underestimated. The result, as calculated, is higher than in other Mediterranean areas like Arrábida Natural Park, Portugal (12.1%; [ 26 ]), Monti Sicani Regional Park, Italy (12.7%, [ 27 ]) or the northwest Basque Country (12%; [ 28 ]), and lower than that of Serra de São Mamede, Portugal (23.1%; [ 29 ]), in the same biogeographical region, or that of Keelakodankulam, India (20.17%; [ 30 ]), in a quite distant and floristically different area.

The EI was conceived [ 31 ], and is usually calculated, for species and infraspecific taxa. Nevertheless, as the present paper focuses on families too, we calculated the EI for this taxonomic category (excluding the 15 non-native families, not present in the flora used as a basis). We found a familiar EI of 68.21%, indicating that almost three-quarters of the families in the area considered contained plants used in pharmaceutical ethnobotany. We believe that it would be of interest to calculate this parameter for other ethnofloras, in order to be able to compare the rates of families hosting useful plants.

2.1. Most Reported Families

Among the 10 most cited families ( Table 1 ), which represent 57.34% of total use reports, we find some of the most relevant in ethnobotanical studies in the Mediterranean, namely Lamiaceae (15.40%), Asteraceae (11.90%) or Rosaceae (5.57%). These are large in terms of number of taxa, Asteraceae being the largest one [ 32 ]. These families are cosmopolitan and well represented in our territories, but also, particularly in Lamiaceae and Rosaceae, they are economically very significant, thanks to aromatic plants in Lamiaceae [ 33 ] and edible fruits and ornamental uses in Rosaceae [ 34 ]. In ethnofloristic works conducted in Mediterranean areas, these three families are almost always predominate at the top of the list, and also some others such as Fabaceae and Apiaceae [ 11 , 12 , 26 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ]. From this, the simple but clear idea can be deduced, that people use with preference (or at least importantly) the plants that they easily find not far from their place of daily life, as Johns et al. [ 46 ] and Bonet et al. [ 47 ] stated.

Top ten families by citations, with number of use reports (UR), UR percentage and number of taxa with uses present in the flora of the territories studied.

| Family | UR | UR (%) | Number of Taxa with Medicinal Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lamiaceae | 7336 | 15.40 | 75 |

| Asteraceae | 5667 | 11.90 | 116 |

| Rosaceae | 2652 | 5.57 | 57 |

| Malvaceae | 2298 | 4.82 | 13 |

| Adoxaceae | 1971 | 4.14 | 3 |

| Apiaceae | 1661 | 3.49 | 26 |

| Amaryllidaceae | 1544 | 3.24 | 8 |

| Oleaceae | 1468 | 3.08 | 9 |

| Pinaceae | 1383 | 2.90 | 10 |

| Rutaceae | 1329 | 2.79 | 12 |

In addition, partly due to the restructuring of families following the APG IV last update [ 48 ], in which Sterculiaceae and Tiliaceae have become part of the family Malvaceae, this latter family also appears in the top 10 most reported families, with 4.82%.

The remaining most quoted families are Adoxaceae (4.14%), Apiaceae (3.49%), Amaryllidaceae (3.24%), Oleaceae (3.08%), Pinaceae (2.90%) and Rutaceae (2.79%). Four of these families (Apiaceae, Oleaceae, Pinaceae, Rutaceae) have not been the object of any recent systematic restructuring, and they are classically important in terms of medicinal taxa. Conversely, the Adoxaceae, with only ca. 225 species worldwide [ 49 ], and just six of them in the studied area [ 25 ], now host Sambucus nigra , one of the most used plants in the Mediterranean region and, in particular, in the Catalan-speaking territories [ 50 , 51 ], which has recently been transferred from the Caprifoliaceae. Similarly, the Amaryllidaceae exhibit a significant rate owing to the fragmentation of the Liliaceae lato sensu in several families and the attribution of genus Allium to this family, which is also very relevant in Mediterranean pharmaceutical ethnobotany [ 42 ].

Moerman [ 20 ] concluded that although in a random universe the size of a family would be the best predictor of its medicinal potential in number of taxa, the Asteraceae contain more medicinal plants than random would indicate, so that size is not the only condition for this success. Moerman et al. [ 21 ] found, through a comparative analysis of several geographically distant medicinal floras, that the five most important medicinal plant families in four very differentiated regions (North America, Korea, Kashmir, Chiapas highlands) were delineated by only nine plant families (Araceae, Bignoniaceae, Ericaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Loganiaceae, Malvaceae, Rosaceae, Solanaceae), accounting for the existence of a global pattern of human knowledge. Indeed, to include a fifth area (Ecuador), only three more families were necessary (Apiaceae, Asteraceae, Lamiaceae). In the same line, six out of the top ten families in the present study are among the 14 most quoted ones in the five North American, Mesoamerican, South American and Asian territories investigated by Moerman et al. [ 21 ], those reported above plus Liliaceae and Ranunculaceae. The only top families in this paper not appearing in Moerman et al. [ 21 ] are Adoxaceae, Oleaceae, Pinaceae and Rutaceae (considering the Amarillydaceae included in the Liliaceae lato sensu , as this family was referred to in the aforementioned work).

2.2. Over- and Underuse of Plant Groups and Plant Families

Results for the over- and underused high taxonomic groups are shown in Table 2 . Gymnosperms and monocots are the only two groups that differ from the common proportion. The observed proportion was 0.1709 and ranges from 16% and 18% with 95% of probability and, consequently, we can refuse the null hypothesis for these groups. While monocots are underused, gymnosperms are overused. The proportion of used monocots is very low, and the 95% posterior credible interval very narrow. Contrarily, gymnosperms show the highest proportion of the used plants, and a larger interval, possibly related, according to Weckerle et al. [ 22 ], to their small number of species.

Over- and underused high taxonomic groups in the Catalan-speaking territories.

| Taxonomic Group ( ) | Inf. | Sup. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gymnosperms * | 34 | 19 | 0.394 | 0.56 | 0.712 |

| Eudicots-superrosids | 1401 | 273 | 0.175 | 0.19 | 0.216 |

| Pteridophytes | 69 | 18 | 0.172 | 0.26 | 0.376 |

| Eudicots-superasterids | 2178 | 395 | 0.166 | 0.18 | 0.198 |

| ANA-grade | 1 | 1 | 0.158 | 1.00 | 0.987 |

| Magnoliids | 7 | 3 | 0.157 | 0.43 | 0.755 |

| Early-diverging eudicots | 175 | 22 | 0.085 | 0.13 | 0.183 |

| Monocots * | 782 | 63 | 0.064 | 0.08 | 0.102 |

| Total/common | 4647 | 794 | 0.160 | 0.17 | 0.182 |

n j : number of plant taxa in the overall flora; x j : number of medicinal plant taxa; θj : proportion of medicinal species; Inf. and Sup.: The 95% posterior credible interval of θj. * Taxonomic groups differing from H 0 .

The families whose 95% posterior credible interval lies above the interval of the overall proportion of flora (0.160, 0.182) are listed in Table 3 . These overused families are families represented by a small number of genera, and most of them having medicinal uses, that is, with high proportions. The preponderance of woody species over herbaceous among the most used has been discussed by several authors [ 20 , 52 , 53 , 54 ]. Fagaceae, Rutaceae and Cannabaceae are the three most overused families. The woody families such as Fagaceae, Pinaceae and Cupressaceae (the last two gymnosperms) together with some shrubby families such as Buxaceae, Rhamnaceae and Ericaceae are overrepresented in the medicinal Catalan flora, but in approximately the same proportion as weedy plant families, such as Equisetaceae, Asphodelaceae or Urticaceae.

Overused plant families in the studied area.

| Family ( ) | Inf. | Sup. | Margin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fagaceae | 15 | 11 | 0.476 | 0.73 | 0.890 | 0.294 |

| Rutaceae | 15 | 11 | 0.476 | 0.73 | 0.890 | 0.294 |

| Cannabaceae | 3 | 3 | 0.398 | 1.00 | 0.994 | 0.216 |

| Pinaceae | 15 | 9 | 0.354 | 0.60 | 0.802 | 0.172 |

| Cucurbitaceae | 13 | 8 | 0.351 | 0.62 | 0.823 | 0.169 |

| Equisetaceae | 8 | 5 | 0.299 | 0.63 | 0.863 | 0.117 |

| Cupresaceae | 15 | 8 | 0.299 | 0.53 | 0.753 | 0.117 |

| Oleaceae | 15 | 8 | 0.299 | 0.53 | 0.753 | 0.117 |

| Buxaceae | 2 | 2 | 0.292 | 1.00 | 0.992 | 0.110 |

| Apocynaceae | 13 | 7 | 0.289 | 0.54 | 0.770 | 0.107 |

| Rhamnaceae | 13 | 7 | 0.289 | 0.54 | 0.770 | 0.107 |

| Myrtaceae | 4 | 3 | 0.284 | 0.75 | 0.947 | 0.102 |

| Lamiaceae | 207 | 67 | 0.264 | 0.32 | 0.390 | 0.082 |

| Asphodelaceae | 12 | 6 | 0.251 | 0.50 | 0.749 | 0.069 |

| Urticaceae | 10 | 5 | 0.234 | 0.50 | 0.766 | 0.052 |

| Crassulaceae | 38 | 14 | 0.234 | 0.37 | 0.528 | 0.052 |

| Ericaceae | 22 | 9 | 0.232 | 0.41 | 0.615 | 0.050 |

| Rosaceae | 190 | 54 | 0.225 | 0.28 | 0.352 | 0.043 |

| Solanaceae | 37 | 13 | 0.218 | 0.35 | 0.514 | 0.036 |

| Araceae | 11 | 5 | 0.211 | 0.45 | 0.723 | 0.029 |

| Polypodiaceae | 3 | 2 | 0.194 | 0.67 | 0.932 | 0.012 |

| Adoxaceae | 6 | 3 | 0.184 | 0.50 | 0.816 | 0.002 |

n j : number of plant taxa in the overall flora; x j : number of medicinal plant taxa; θj : proportion of medicinal species; Inf. and Sup.: The 95% posterior credible interval of θj .

The families whose 95% posterior credible interval lies below the interval of the overall proportion of flora (0.160, 0.182) are listed in Table 4 . Usually, these are families comprising a large number of species in the local flora and with little representation in the medicinal one. In the present study, only nine families are underused, Cyperaceae, Plumbaginaceae and Poaceae, the most underused. Three families, Poaceae, Juncaceae and Cyperaceae belong to the underrepresented high group of monocots. In the present study, most of members of the underused families are herbaceous plants.

Underused plant families in the studied area.

| Family ( ) | Inf. | Sup. | Margin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabaceae | 383 | 45 | 0.089 | 0.12 | 0.154 | 0.006 |

| Ranunculaceae | 126 | 9 | 0.038 | 0.07 | 0.130 | 0.030 |

| Brassicaceae | 256 | 22 | 0.058 | 0.09 | 0.127 | 0.033 |

| Orobanchaceae | 78 | 4 | 0.021 | 0.05 | 0.125 | 0.035 |

| Caryophyllaceae | 233 | 18 | 0.050 | 0.08 | 0.119 | 0.041 |

| Juncaceae | 45 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.115 | 0.045 |

| Poaceae | 417 | 22 | 0.035 | 0.05 | 0.079 | 0.081 |

| Plumbaginaceae | 80 | 1 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.067 | 0.093 |

| Cyperaceae | 131 | 2 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.054 | 0.106 |

2.3. Genera with Folk Medicinal Uses

The 120 families recorded are represented herein by 432 genera. If we analyse the number of genera per family, the results vary slightly, and families with more genera are Asteraceae (52), Fabaceae (30) and Lamiaceae (25). Apart from the two families with the most use reports, here appears the Fabaceae family (765 UR, 1.61%), although not being among the top ten. Despite not having a high percentage, Fabaceae is a relevant family in the Mediterranean flora (even being indicative of the Mediterranean character of a territory; [ 55 ]) and ethnoflora [ 42 ]. Conversely, Adoxaceae with a large number of use reports (1,971 UR, 4.14%) is very asymmetrically distributed in only two genera, Sambucus (99.9%) and Viburnum (0.1%), which would be explained by the change of family, since they previously belonged to the Caprifoliaceae, yet with the APG system, a new familiar delimitation of the Adoxaceae was created for these two genera, and for three more not present in our territory. On the other hand, there are 60 botanical families in which all the reports are grouped in a single genus. Some examples, representing pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms, are the Equisetaceae, a family with 578 UR exclusive of the genus Equisetum , the only one in the family to be present in the studied area, and the Taxaceae and the Juglandaceae families, with 17 and 570 UR respectively, exclusively represented by their corresponding single species growing in the area, Taxus baccata L. and Juglans regia L. There are also families that concentrate all the medicinal records in one genus, although they have other representatives in the territories studied like Liliaceae stricto sensu, with six genera in the concerned area, but with all UR from only one, Lilium .

2.4. Plants not Appearing in the Flora of the Studied Area

Concerning plants not appearing in the flora of the territories studied ([ 25 ]; see materials and methods for details), there are 15 families not present in the flora of our territory, representing 12.5% of the total number of families. Examples are Actinidiaceae, Myristicaceae and Zingiberaceae. These families contain very renowned and used medicinal plants, some of them used first for food purposes, such as Actinidia chinensis Planch., Myristica fragrans Houtt. and Zingiber officinalis Roscoe. In addition, there are 62 taxa not present in our territory, yet belonging to families that nonetheless are present thanks to other genera; this is the case of Cinnamomum verum J.Presl (Lauraceae), Cocos nucifera L. (Arecaceae) or Coffea arabica L. (Rubiaceae), to give some examples. Even the two most quoted families, in terms of UR, Asteraceae and Lamiaceae, very abundant in wild representatives in the region under investigation, include non-native plants in the local ethnoflora, some examples are Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench and Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) Bertoni, and Monarda didyma L., Ocimum basilicum L., and Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton, respectively. It is important to emphasise that a number of plants ethnobotanically used are not present in the Catalan flora [ 25 ], and yet they are important in local ethnobotany. Indeed, in a work in progress regarding in the Catalan linguistic area we are recording a non-negligible number and percentage of UR attributed to non-native plants [ 56 ].

2.5. Most Reported Troubles

We grouped the troubles or systems addressed in 15 categories ( Table 5 ). The four most addressed troubles, representing 61.01% of all use reports, are disorders of the digestive and nutritional system (11,754 UR, 24.68%), followed at a great distance (approximately half of the use reports) by respiratory system disorders (6418 UR, 13.47%), skin or subcutaneous tissue disorders (5588 UR, 11.73%) and circulatory system and blood disorders (5299 UR, 11.13%). Most uses are addressing mild and chronic illnesses, which agrees with the most widespread idea on the main focuses of pharmaceutical ethnobotany and phytotherapy in general [ 57 ], but in some cases, they are also pointing to acute and more severe health troubles, like cardiovascular and pulmonary ones, and even cancer.

Medicinal uses grouped in troubles or systems addressed with number and percentage of use reports (UR).

| Troubles or Systems Addressed (Code) | UR | UR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Digestive system and nutritional disorders (DN) | 11,754 | 24.68 |

| Respiratory system disorders (R) | 6418 | 13.47 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (SS) | 5588 | 11.73 |

| Circulatory system and blood disorders (CB) | 5299 | 11.13 |

| Infections and infestations (II) | 3831 | 8.04 |

| Genitourinary system disorders (G) | 3618 | 7.60 |

| Musculoskeletal system disorders and traumas (MT) | 3493 | 7.33 |

| Nervous system and mental disorders (NM) | 2546 | 5.35 |

| Sensory system disorders (S) | 1975 | 4.15 |

| Pain and inflammations (PI) | 1224 | 2.57 |

| Pregnancy, birth and puerperal disorders (PBP) | 554 | 1.16 |

| Endocrine system and metabolic disorders (EM) | 470 | 0.99 |

| Tonic and restorative (TR) | 406 | 0.85 |

| Poisoning (P) | 361 | 0.76 |

| Immune system disorders and neoplasia (IN) | 93 | 0.20 |

2.6. Relationship between Families and Uses

One of the most important aims of this work is to study the possible relationships between plant families and categories of medicinal uses, i.e., troubles or systems addressed. We analysed the correspondences between families and health diseases, and will now comment on the most relevant findings.

A general consideration of the relationship between families and UR in a phylogenetic frame ( Figure 1 ) shows, within the angiosperms, that the superasterids clearly host the largest number of uses, as well as the largest number of families with an important number of UR, in comparison with the remaining large groups. In each of these, only one or a few families play a protagonist role, such as Malvaceae, Rosaceae and Rutaceae in the superrosids, Ranunculaceae in the eudicots, and Amaryllidaceae and Poaceae in the monocots. Magnoliids and basal angiosperms are not of much significance in terms of UR. It is worth mentioning that, in the asterids, most UR are concentred in the most evolved clade, formed by the campanulids plus the lamiids. As for the gymnosperms, the Pinaceae accumulate most UR.

Heatmap depicting the distribution of use records among plant families and the addressed troubles/systems. Abbreviations, as quoted in the figure, are as follows. CB, circulatory system and blood disorders; PI, pain and inflammations; DN, digestives system and nutritional disorders; P, poisoning; EM, endocrine system and metabolic disorders; PBP, pregnancy, birth and puerperal disorders; G, genitourinary system disorders; II, infections and infestations; IN, immune system disorders and neoplasia; NM, nervous system and mental disorders; MT, musculoskeletal system disorders and traumas; SS, skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders; R, respiratory system disorders; S, sensory system disorders; TR, tonic and restorative.

The analysis of the percentages of UR related to the different troubles/systems within each family ( Figure 2 ) denotes that the highest rates are rather widespread at the phylogenetic scale. In any case, it clearly appears that a large number of families have exhibit digestive and nutritional problems as the most treated ones (mean percentage: 24.56), which is in agreement with the above-mentioned idea that ethnobotany and phytotherapy importantly address mild, daily health constraints. Nevertheless, in the vast majority of families, there are also strong rates of uses focused on circulatory and blood, and respiratory ailments (mean percentages: 14.30 and 11.03, respectively), most of which are not so mild. Finally, some disorders are very scarcely addressed in the pharmaceutical ethnoflora under consideration, such as those linked to endocrine and metabolic, and immune systems, as well as to neoplasia (mean percentages: 0.35 and 0.16, respectively).

Heatmaps depicting percentages of use reports related to the different troubles/systems within each family, and percentages of use reports of families for each trouble/system. Abbreviations, as quoted in the figure, are as follows. CB, circulatory system and blood disorders; PI, pain and inflammations; DN, digestives system and nutritional disorders; P, poisoning; EM, endocrine system and metabolic disorders; PBP, pregnancy, birth and puerperal disorders; G, genitourinary system disorders; II, infections and infestations; IN, immune system disorders and neoplasia; NM, nervous system and mental disorders; MT, musculoskeletal system disorders and traumas; SS, skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders; R, respiratory system disorders; S, sensory system disorders; TR, tonic and restorative.

If we analyse the percentage of use reports of families for each disorder ( Figure 2 ), 10 out of the 15 trouble/system categories established are dominated by the two families with most UR in general, Lamiaceae (six categories: Circulatory system and blood disorders; pain and inflammation; digestive system and nutritional disorders; skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders; respiratory system disorders; tonic and restorative) and Asteraceae (four categories: Endocrine system and metabolic disorders; infections and infestations; musculoskeletal system disorders and traumas; sensory system disorders). The well-known important presence and diversity of essential oil compounds in the Lamiaceae [ 58 ] account—together with the size of the family, as already commented—for its relevance in many medicinal fields related to antiseptic properties, which could explain the prevalence in digestive, dermic and respiratory disorders. Similarly, the abundance, among other compounds, of terpene compounds (including sesquiterpene lactones) in the Asteraceae [ 59 ] is logically at the basis of their uses for different ailments, again considering the size and diversity within the family.

Concerning Asteraceae, we want to underline two troubles in particular. First, the uses for the musculoskeletal system disorders and traumas, explained by Arnica montana L. (335 UR, 52.59%) and other species of this family ( Arctium minus (Hill) Bernh., Doronicum grandiflorum Lam., all of the Inula genus, Jasonia saxatilis (Lam.) Guss., Pallenis spinosa (L.) Cass. and Pulicaria dysenterica (L.) Gaertn.) referred to with the popular name “ àrnica ” (189 UR, 29.67%). In total, the ethnotaxon constituted by Arnica montana and the aforementioned related taxa accumulates 82.26% of the Asteraceae UR employed for musculoskeletal system disorders and traumas, specially bruises. This medicinal plant complex has been well studied in the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands from a botanical and ethnopharmacological point of view [ 60 ]. Secondly, the uses for the endocrine system and metabolic disorders are due to hypoglycaemic activity (259 UR, 98.48%) of several species of the genus Centaurea , representing, with 180 UR, the 68.44% of this property, abundantly registered in this genus [ 61 ].

In the other five categories, the prominence of a family in the treatment of a problem is basically due to one or a very few taxa. Amaryllidaceae are the most quoted in fighting against poisoning cases (21.33%), with all the reports concentrated on a few species of the genus Allium , which has been reported with this function, and is, for instance, used worldwide against snakebites [ 62 , 63 ]. The dominance of Rutaceae in the pregnancy/childbirth/puerperal treatment is basically explained (27.44%) by the genus Ruta , with three species. This family is closely followed by the Saxifragaceae (22.56%), because of a few species of Saxifraga . Irrespective of the fact of containing plants used for food purposes in ethnobotany, both genera mentioned are among those most famous abortifacients recorded in folk medicine [ 64 , 65 ], this proving their relationship with the life period concerned (e.g., labour inducing, post-labour coadjuvant, dangerous in pregnancy).

Poaceae are the most relevant regarding the genitourinary system (17.66%), mostly by Zea mays L., followed at a considerable distance by Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers., both (especially the first one) are much reputed as diuretic [ 66 ]. Ranunculaceae are the top family in addressing neoplasia (21.51%), because of Ranunculus parnassifolius L., a high mountain plant much appreciated popularly for this purpose in a Pyrenean region [ 45 , 67 ]. Finally, Malvaceae leads the ranking in troubles related to the nervous system and mental disorders (29.58%). The success in this use is basically explained by the genus Tilia (733 UR, 97.34%)—recently incorporated into the Malvaceae, where Tiliaceae have been merged—very popular and largely studied as hypnotic, sedative and tranquilizer [ 68 , 69 ].

2.7. Phylogenetic Distribution of Families with Medicinal Use

To investigate the degree of phylogenetic clustering of families for each trouble or system, and to detect hot nodes for further studies, we mapped the reported medicinal uses grouped in the 15 troubles or systems addressed on the phylogeny of the families.

A robust hot node appears in three medicinal groups: immune system disorders and neoplasia; pain and inflammation; and pregnancy, birth and puerperal disorders. The hot node is constituted by the Iridaceae and three families classically included in the Liliaceae l.s., Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae, and Asphodelaceae. The last three families also constitute a hot node clade for tonic and restorative. In addition, only Amaryllidaceae and Asparagaceae are hot nodes for the endocrine system and metabolic disorders.

Tonic and restorative activities also have another robust hot node, constituted by Betulaceae, Juglandaceae and Fagaceae. For the endocrine system and metabolic disorders, the clade of Apiaceae and Araliacaeae was detected as relevant.

Finally, two robust hot nodes appear for poisoning, on the one hand, Cucurbitaceae and Coriariaceae, and on the other hand Malvaceae, Cistaceae and Thymelaeaceae.

2.8. Diversity Indices

The results of the Shannon and Margalef indices for each family are shown in Supplementary Materials . Although the values of the two indices are zero for several families and some of them present low values, such as the Vitaceae (H = 0.01 and k = 0.11), other families show a moderate diversity. The family Asteraceae is the one that presents the highest diversity according to the Shannon index (H = 1.45), while, according to the Margalef index, the Campanulaceae is the family with the greatest diversity (k = 0.70). These differences are due to the fact that the Margalef index is higher when the number of taxa and the number of use reports are equal or close within a family, while if there are many use reports for a few taxa, the diversity decreases. Despite showing a different sensitivity to the variation in the number of taxa and use reports, both indices are well correlated, (r = 0.841, p < 0.001 for a whole dataset). For this reason, we believe the two indices are robust and can be used to measure ethnobotanical diversity, even taking into account their limitations.

2.9. Needs for Further Research

This study draws our attention to the relevance of the family taxonomic level in ethnobotany. A few points in which further research is needed have arisen from our analyses.

The taxonomy of specific and infraspecific taxa in ethnobotanical works is usually given, as is logical, according to local floras but, as from the consolidation of the APG family updates, almost all papers use its system for families, which is not coincidental to those used in floras before APG rearrangements. This creates a difficulty in the comparison of data related to families in ethnobotanical research, either in one area or in different ones: the number of families and, more importantly, their rates of presence in each ethnoflora vary when applying the last classical [ 70 ] or the APG systems. An international effort should be carried out to implement the APG family system in the ethnobotanical databases in order to facilitate suitable meta-analytic work. Although new prospects will always be positive for a bigger and better knowledge of plant medicinal uses, at present a considerable amount of ethnobotanical information is already accumulated in many parts of the world, so that this is the appropriate moment to undertake comparative analyses between close and not so close ethnofloras, following the initiative, here seconded, pioneered by of Moerman [ 20 ] and followed by Weckerle et al. [ 22 ] or Dal Cero et al. [ 23 ], for which adopting the APG familiar treatment is important.

Given their relevance in most ethnofloristic surveys, the role of commercially-acquired plants in the ethnoflora, and the comparison of their uses with those of autochthonous or allochthonous plants currently present in the flora —and, then, the comparison between these two categories—is a subject that should be addressed in detail in the different major geographical areas of the world. At the family level, as treated in this work, 15 families not present in the local flora (apart from some others present hosting non-native taxa) have been recorded in a relatively small territory. This is a consequence of cultural exchanges through time, recently accelerated by the globalisation process.

Finally, a relevant aspect is a relationship between ethnobotany and phytochemistry (the latter leading to pharmacology and linked to phylogeny). Although there is not an obvious and unidirectional relationship, and little is known about phytochemical composition as compared with evolutionary aspects [ 71 ], ethnobotanical knowledge has systematic and evolutionary significance [ 16 , 17 , 71 ], and thus can help in progressing in the necessary multidisciplinary approach to ethnopharmacology and ethnomedicine. Projecting data such as those treated here in a phylogenetic framework has allowed us to detect hot nodes, richer in families useful in pharmaceutical ethnobotany. Further deeper combination of ethnobotanical and phylogenetic information within one family or a group of a few related families could lead to detecting and predicting taxa useful for particular troubles. Several ethnobotanical works include the phytochemical and/or pharmacological validation of the folk uses reported or discuss ethnobotanical knowledge in the light of chemical plant composition [ 13 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 ], and this will probably be more common in the near future. Family level is particularly adequate to be addressed for establishing relationships between chemical composition, phylogenetic aspects and ethnobotanical knowledge, the three fields confronted either two by two or altogether.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. data sources and field work methods.

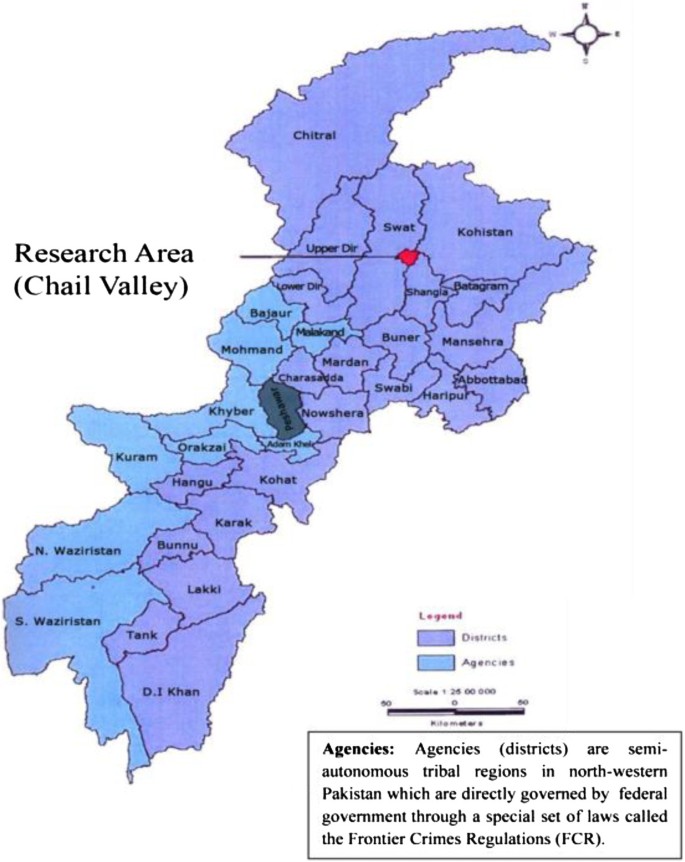

In this study, we used data on plants and their folk medicinal uses obtained from 44 ethnobotanical research prospects ( Supplementary Material S1 ) carried out in the Catalan linguistic domain ( Figure 3 ). We utilized the use report (hereinafter, UR), i.e., the report of the use of one taxon by an informant, as the unit of measurement [ 76 ]. Veterinary uses are excluded, and human medicinal uses are classified in 15 troubles or systems categories, according to Cook [ 77 ] with minor modifications. We grouped some categories by affinity in order to achieve more robustness in the analyses, as some of them had very few reports. The names of the troubles or system categories have remained as in Cook’s classification ( Table 5 ), and we just added a new category: tonic and restorative.

Map of the territories studied within Europe and the Catalan linguistic area. Dots indicate the areas with prospections analysed in the present paper.

The fieldwork method used in these researches was the semistructured interview [ 9 , 78 ], always taking into account the code of ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology [ 79 ], complemented by the collection of plant specimens to be identified and deposited in public herbaria. All interviews were digitalised, transcribed and introduced into our database that contains all ethnobotanical data (on medicinal, food and other uses) collected.

3.2. Data Analysis

The simple quantitative analyses of descriptive statistics for categories (species, families, and medicinal uses) and the construction of families and disorders matrix ( Supplementary Material S2 ) were carried out with Excel software (Microsoft Office, 2010). Results were summarized as heatmaps using the R Phytools package ([ 80 ]; R version 3.6.0, [ 81 ]) and the family-level phylogeny of land plants from Zanne et al. [ 82 ], pruned to our taxonomic dataset. We tested whether each node in the phylogeny was significantly more represented by a family in a given category of trouble/system than would be expected by chance alone (i.e., hot nodes; [ 83 ]), using the nodesig test originally implemented in the PHYLOCOM software [ 84 ] and adapted for R by Abellán et al. [ 85 ].

With the aim of assessing the general state of pharmaceutical ethnobotanical knowledge in the studied area, we calculated the ethnobotanicity index (EI; [ 31 ]), which is the quotient between the number of plants used and the total number of plants that constitute the flora of the territory, expressed as a percentage. For this purpose, only the plants present in the Catalan linguistic area’s flora [ 25 ] were considered, and 5,500 taxa at specific and infraspecific level (Sáez, 2019, pers. comm.) were adopted. Furthermore, we adapted this index to calculate it for families as well.

3.3. Bayesian Method to Evaluate over- and Underused Taxonomic Groups

To evaluate over- and underused flora for the Catalan linguistic domain, 794 medicinal plant taxa at specific and infraspecific levels with uses reported and included of the flora of the studied area [ 25 ], belonging to 103 families, were recovered from the ethnobotanical database. The total flora for the same families of the studied area is 4,647 taxa [ 25 ]. These families were assigned to eight taxonomic groups: ANA-grade, early-diverging eudicots, eudicots-superasterids, eudicots-superrosids, gymnosperms, magnoliids, monocots and pteridophytes, following Chase et al. [ 48 ].

In this scenario our null hypothesis ( H 0 ) is the following: For a taxomic group ( j ), the proportion of medicinal taxa ( θj ) is equal to the overall proportion ( θ ), where θj is a random variable uniformily distributed between 0 and 1 (prior probability). The posterior probability can be estimated, its distribution will be conditioned by the observed data (see [ 22 ] for more details). Probability distribution differences from the common proportion are assessed by all families.

Calculations of the intervals of the most probable values of θ and θ j were carried out by the function which returns the inverse of density of beta probability (INV.BETA.N) implemented in Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2011).

3.4. Diversity Indices

In order to quantify the diversity of taxa within the families referred by the informants, we calculated two diversity indices ( Supplementary Material S2 ). The first one, the Shannon diversity index [ 86 ] from the theory of communication and largely used in ecology, has also been calculated in some previous ethnobotanical studies [ 87 , 88 ]. This index, calculated according to the formula H fam = −Σ p tax log 2 p tax , where p tax , represents the citation frequency of each taxon and assesses the ethnobotanical taxa diversity within each family, i.e., the family richness from the ethnobotanical point of view. The second index, k = log S/log N where S is the number of species and N the number of individuals, proposed by Margalef [ 89 ] was adapted and used for the first time in an ethnobotanical study to calculate the diversity within the botanical families following the formula: k = log T/log UR, where T represents the number of taxa. Pearson’s coefficient correlation (r) was calculated between these two datasets.

4. Conclusions

The medicinal ethnoflora of the Catalan-speaking territories includes 894 taxa belonging to 120 botanical families of vascular plants. The ethnobotanicity index (EI) is 14.44% and the familial EI is 68.21% for the studied area. This parameter allows us to compare the present data with other ethnofloras.

The most common families in the Mediterranean area, such as Lamiaceae (14.40%), Asteraceae (11.90%) or Rosaceae (5.57%) are among the most cited families which represent 57.34% of total use reports. Fagaceae, Rutaceae and Cannabaceae are the three most overused families and Cyperaceae, Plumbaginaceae and Poaceae the most underused.

The digestive and nutritional system disorders (11,754 UR, 24.68%), the respiratory system disorders (6418 UR, 13.47%), skin or subcutaneous tissue disorders (5588 UR, 11.73%) and circulatory system and blood disorders (5299 UR, 11.13%) representing 61.01% of all use reports are the most cited troubles.

To investigate the degree of phylogenetic clustering of families for each trouble or system and detect hot nodes for further studies we mapped the reported medicinal uses grouped in the 15 troubles or systems addressed on the phylogeny of the families.

In the phylogenetic reconstruction, a robust hot node appears in three medicinal groups: immune system disorders and neoplasia; pain and inflammation; and pregnancy, birth and puerperal disorders constituted by the Iridaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae, and Asphodelaceae. The last three families also constitute a hot node clade for tonic and restorative. Tonic and restorative activities also have another robust hot node, constituted by Betulaceae, Juglandaceae and Fagaceae. For the endocrine system and metabolic disorders, the clade of Apiaceae and Araliacaeae was detected as relevant. Two robust hot nodes appear for poisoning, on the one hand Cucurbitaceae and Coriariaceae, and on the other hand Malvaceae, Cistaceae and Thymelaeaceae. These results centred on the familial level are appropriate when establishing relationships between chemical composition, phylogenetic aspects and ethnobotanical knowledge.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the people who participated as informants in this work, who are, in fact, true collaborators, for sharing their time and knowledge. We are grateful to Jaume Pellicer (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew) for providing us with the family-level phylogenetic reconstruction, and Samuel Pyke (Barcelona’s Botanic Garden) for the revision of the English language.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/10/1/163/s1 , S1 . References used to elaborate the data matrix analysed; S2 . Families and disorders matrix, and diversity indices.

Author Contributions

The subject and its reach have been designed by A.G., J.V. and T.G., with the assistance of the remaining authors in different points. A.G., M.P. and U.D. performed the database work to select and treat the ethnobotanical information of the areas chosen. O.H. carried out the phylogenetically informed analyses. A.G. and T.G. carried out the statistical analyses. A.G., J.V. and T.G. wrote a first version of the manuscript, which was read and discussed by the remaining authors. Finally, A.G. and J.V. prepared the final version of the manuscript, which was read and approved by all the authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was supported by projects 2017SGR001116 from the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan Government), PRO2017-S02VALLES and PRO2020-S02VALLES from the Institut d’Estudis Catalans (IEC, Catalan Academy of Sciences and Humanities), and CSO2014-59704-P and CGL2017-84297-R from the Spanish Government. AG received a predoctoral grant of the Universitat de Barcelona (APIF 2015-2018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This meta-analytic study, not implying any clinical or similar experiment, was conducted according to the guidelines of the International Society of Ethnobiology.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

- Ethnobotany

- Cultural anthropology

- Plant science

- Get an email alert for Ethnobotany

- Get the RSS feed for Ethnobotany

Showing 1 - 13 of 25

View by: Cover Page List Articles

Sort by: Recent Popular

A scoping review of the use of traditional medicine for the management of ailments in West Africa

Selassi A. D’Almeida, Sahr E. Gbomor, [ ... ], Morẹ́nikẹ́ Oluwátóyìn Foláyan

Traditional utilization of bamboo in the Central Siwalik region, Nepal

Bishnu Maya K. C., Janardan Lamichhane, Sanjay Nath Khanal, Dhurva Prasad Gauchan

Ethnobotanical study of Mandi Ahmad Abad, District Okara, Pakistan

Mubashrah Munir, Sehrish Sadia, [ ... ], Rahmatullah Qureshi

Indigenous knowledge and quantitative ethnobotany of the Tanawal area, Lesser Western Himalayas, Pakistan

Fozia Bibi, Zaheer Abbas, [ ... ], Rainer W. Bussmann

Ethnobotanical and conservation studies of tree flora of Shiwalik mountainous range of District Bhimber Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan

Humaira Khanum, Muhammad Ishtiaq, [ ... ], Samy Sayed

Alien woody plants are more versatile than native, but both share similar therapeutic redundancy in South Africa

Kowiyou Yessoufou, Annie Estelle Ambani, Hosam O. Elansary, Orou G. Gaoue

An ethnobotanical study of wetland flora of Head Maralla Punjab Pakistan

Muhammad Sajjad Iqbal, Khawaja Shafique Ahmad, [ ... ], Rainer W. Bussmann

Eighty-four per cent of all Amazonian arboreal plant individuals are useful to humans

Sara D. Coelho, Carolina Levis, [ ... ], Juliana Schietti

Inventorization of traditional ethnobotanical uses of wild plants of Dawarian and Ratti Gali areas of District Neelum, Azad Jammu and Kashmir Pakistan

Muhammad Ajaib, Muhammad Ishtiaq, [ ... ], Rohina Bashir

Gender differences in traditional knowledge of useful plants in a Brazilian community

Fernanda Vieira da Costa, Mariana Fernandes Monteiro Guimarães, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias

Quilombola communities in Serra do Mar State Park">Evaluation of conservation status of plants in Brazil’s Atlantic forest: An ethnoecological approach with Quilombola communities in Serra do Mar State Park

Bruno Esteves Conde, Sonia Aragaki, [ ... ], Eliana Rodrigues

Participatory methods on the recording of traditional knowledge about medicinal plants in Atlantic forest, Ubatuba, São Paulo, Brazil

Thamara Sauini, Viviane Stern da Fonseca-Kruel, [ ... ], Eliana Rodrigues

Biodiverse food plants in the semiarid region of Brazil have unknown potential: A systematic review

Michelle Cristine Medeiros Jacob, Maria Fernanda Araújo de Medeiros, Ulysses Paulino Albuquerque

Connect with Us

- PLOS ONE on Twitter

- PLOS on Facebook

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in mersin (turkey).

- 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, Faculty of Pharmacy, Marmara University, Basibuyuk-Istanbul, Turkey

- 2 Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, Faculty of Pharmacy, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Cigli-Izmir, Turkey

- 3 Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mersin University, Yenisehir-Mersin, Turkey

- 4 Department of Sociology, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul University, Fatih-Istanbul, Turkey

- 5 Department of Turkish Language and Literature, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Adana Alparslan Turkes University, Adana, Turkey

- 6 Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, Faculty of Pharmacy, Selcuk University, Selcuklu-Konya, Turkey

This comprehensive ethnobotanical study carried out in Mersin province, which is located in the southern part of Anatolia, east of the Mediterranean Sea, compiles details on plants used in folk medicine and ethnopharmacological information obtained through face-to-face interviews. The aim was to collect and identify plants used for therapeutic purposes by local people and to record information on traditional herbal medicine. Plant specimens were collected in numerous excursions. Additionally, informant consensus factor and use value (UV) were calculated for information gathered. This study identifies 93 plant taxa belonging to 43 families and records their usage in folk medicine; 83 taxa are wild and the remaining 10 are cultivated. The most commonly used plants belong to Lamiaceae, representing 15.0% of the total, while the Rosaceae, Malvaceae, Hypericaceae, Asteraceae and Cupressaceae families each represented another 5.4%. As a result of this investigation, we determine 189 medicinal usages of 93 taxa. The UV values indicate that the most important medicine plants are Hypericum perforatum (0.80), Cedrus libani (0.78), Quercus coccifera (0.77), Arum dioscoridis (0.76) and Juniperus drupaceae (0.74). We observed that most of the drugs are prepared using the infusion method (27.6%). As a conclusion, the study finds that traditional folk medicine usage is still common, especially among the rural population of Mersin.

Introduction

The Mediterranean area, which possesses a unique ecology with various natural features, has been inhabited for millennia and is strongly influenced by human–nature relationships ( Scherrer et al., 2005 ). The tradition of using wild plants for medicinal reasons continues in today’s small rural communities, especially among societies that maintain the cultural bridge between past and present. While the recently developed fast communication technologies connect people in seconds and spread data across vast distances, traditional knowledge still holds importance in daily life. Over the past few decades, efforts to preserve traditional knowledge have escalated around the world, especially in Europe and Mediterranean countries ( Varga et al., 2019 ).

Besides being home to many plants in floristic terms, Turkey is rich in traditional herbal medicine, in addition to its cultural, historical and geographical heritage ( Bulut et al., 2013 ). Ethnobotanical studies show that traditional knowledge of medicinal plants still exists in the Mediterranean Region, especially among elderly ( Agelet, et al., 2003 ). Many scientists have focused on such studies and governmental foundations have increased financial support of this kind of research. The Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has organized studies across the country in the scope of the “Recording of Traditional Knowledge Based on Biological Diversity Project.”

The Taurus Mountains are one of the highlights of the Mediterranean Region with a rich plant diversity ( Everest et al., 2005 ). Mersin has previously been the subject of this kind of scientific research, such as a study on herbal drugs on herbal markets in Mersin, which was conducted throughout the entire province ( Everest et al., 2005 ). Thorough documentation of the traditional use of medicinal plants across the entirety of Mersin province is not presently available. Three districts ( Sargın 2015 ; Sargın et al., 2015 ; Sargin and Büyükcengiz, 2019 ) and some specific areas of the province have been investigated from an ethnobotanical perspective. Another study investigates a small section of the region ( Akaydın et al., 2013 ); however, as one of the largest cities in Turkey, Mersin needs further investigation from an ethnobotanical perspective.

We aim to record the traditional usage of medicinal plants by conducting an ethnobiological study in Mersin that covers various different altitudes and areas representing all ten of its districts.

To this end, we compare the gathered ethnomedicinal data with previous findings from the Balkan and Mediterranean regions. We highlight new plants and usages from the region for future phytochemical and phytopharmacological studies. With further cultivation studies, these findings may demonstrate the potential for economic development for the benefit of local communities.

Hypothesis of this study tests;

a Traditional knowledge is still being used in villages far from the city and main settlement centers,

b Plants are still being used in the more isolated villages.

Materials and Methods

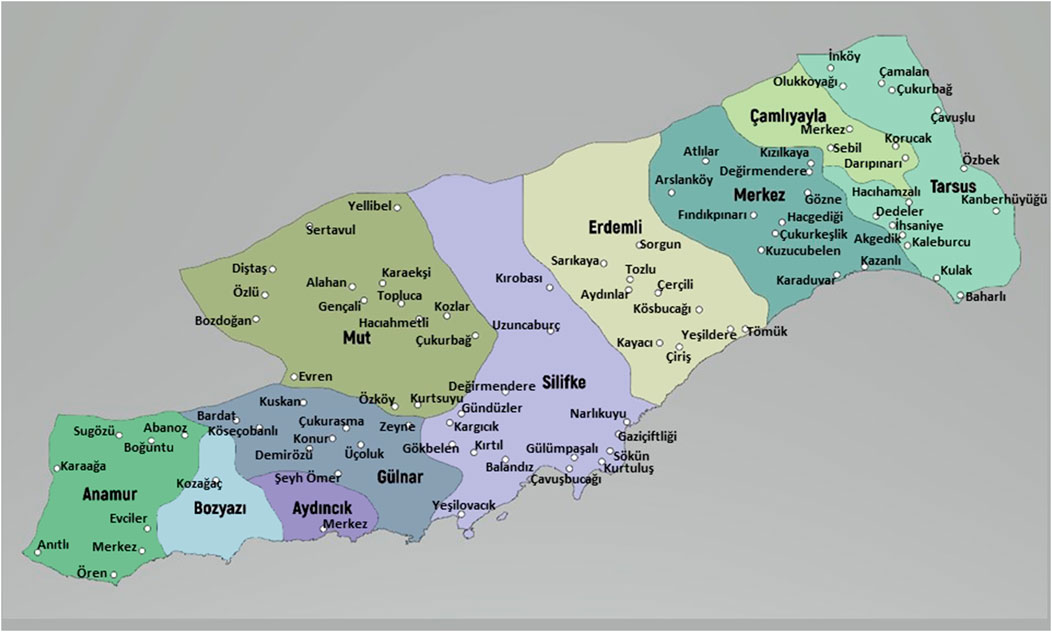

Mersin is a province in southwestern Anatolia, located at a latitude of 36 ° 37′ north and a longitude of 33 ° 35’ east; covering a 15.853 km 2 area with a population of 1,814,468 ( http://www.tuik.gov.tr ) ( Figure 1 ). The majority of the acreage is mountainous (87%) and forestland is 54%. There are ten districts: Anamur, Aydincik, Bozyazi, Camliyayla, Erdemli, Gulnar, Merkez, Silifke, Mut, and Tarsus. This ethnobotanical survey includes 91 villages located in all ten districts of Mersin ( Figure 2 ).

FIGURE 1 . Map of mersin ( https://tr.wikipedia.org ).

FIGURE 2 . Map of visited villages of study area.

The territory of the province consists primarily of the high, rugged, rocky Western and Central Taurus Mountains. The highest point in Mersin is Mount Medetsiz (3,585 m) in the Bolkar Mountains. The altitude decreases from northwest toward the south. Kumpet Mountain (2,473 m), Elma Mountain (2,160 m), Alamusa Mountain (2,013 m), Big Egri Mountain (2,025 m), Kızıl Mountain (2,260 m), Naldoken Mountain (1,754 m), and Kabakli Mountain (1,675 m) are the topographic heights from the Bolkar Mountains in the west.

Karaziyaret Mountain, Tol Mountain, Sunturas Mountain, Balkalesi, Ayvagedigi Mountain, Makam Mountain and Kaskaya Mountain are other important elevations heading toward the south. Mersin is connected to Central Anatolia through Gulek Pass (1,050 m) from the northeast and Sertavul Pass (1,610 m) from northwest.

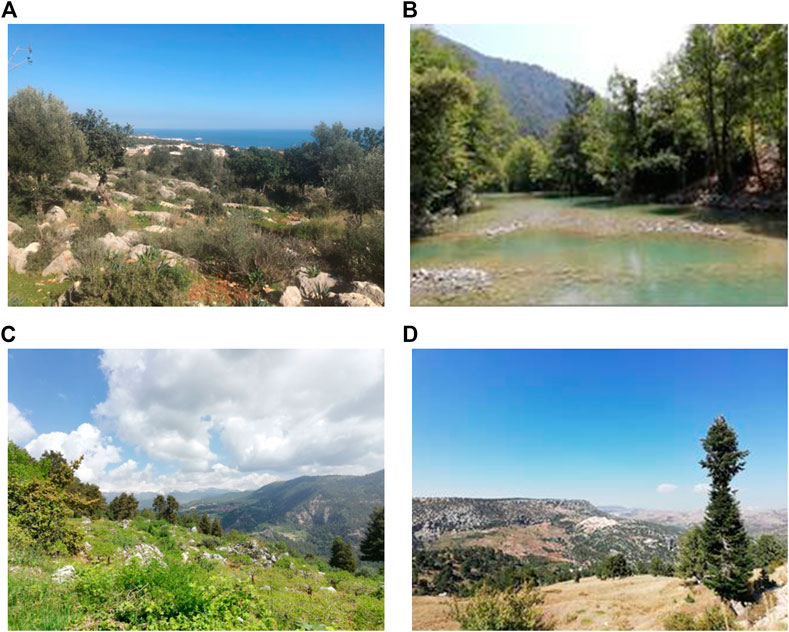

Rivers, streams, atmospheric conditions and the tectonic faults in the region give rise to various plains in the upper reaches of the Taurus Mountains, with altitudes ranging from 700 to 1,500 m. Major plateau areas of Mersin include the highlands of Aslankoy, Gozne, Findikpinari, Sogucak, Bekiralani, Mihrican, Ayvagedigi and Guzelyayla, Camlıyayla, Gulek and Sebil, Sorgun, Kucuk Sorgun, Toros, Kucukfındıklı and Guzeloluk, Balandiz, Uzuncaburc, Gokbelen and Kirobasi, Abanoz, Kas and Besoluk, Bozyazi, Elmagozu and Kozagac, Bardat, Tersakan and Bolyaran, Kozlar, Civi, Dagpazari, Sogutozu and Sertavul ( Figure 3 ). The province is not rich in terms of rivers. The most important rivers are the Goksu and Berdan streams.

FIGURE 3 . View of Camliyayla highland.

The climate is Mediterranean with an annual mean temperature of 22°C and a mean rainfall of 1,096 mm per year ( Meteroloji Genel Müdürlüğü, 2020 ).

The primary sources of income in Mersin are industry (40%), agriculture (30%), and trade/business sector (10%).

The main crops of Mersin are wheat, barley and cotton. Mersin plays an important role in greenhouse cultivation of various agricultural products, of which banana production in Anamur is one of the most famous. Citrus trees, tropical fruits and vegetables are also commonly cultivated.

The vegetation of Mersin district presented here is based on the authors’ own observations and field records. Mersin, which is generally covered with maquis or forest vegetation, contains Mediterranean elements. In areas with maquis, plants such as Ceratonia siliqua L. , Cistus creticus L., Laurus nobilis L., Myrtus communis L. , Nerium oleander L. , Paliurus spina-christi P. Mill., Phillyrea latifolia L. , and Quercus coccifera L. are widespread. Tree species such as Pinus nigra J.F.Arnold subsp. pallasiana (Lamb.) Holmboe, Cedrus libani A. Rich. var. libani , Abies cilicica (Antoine and Kotschy) Carriere subsp. cilicica , Juniperus excelsa M. Bieb. subsp. excelsa, J. foetidissima Willd. , J. oxycedrus L. subsp. oxycedrus, are observed in high altitudes (above 900 m). Lowland forest areas usually consist of Pinus brutia Ten. ( Davis, 1965 ; Davis et al., 1988 ; Güner et al., 2000 ).

Mersin province also has significant dune and halophyte vegetation, including taxa such as Cyperus capitatus Vand., Eryngium maritimum L., Euphorbia paralias L., Pancratium maritimum L., Halimione portulacoides (L.) Aellen, Juncus acutus L. subsp. acutus , J. maritimus Lam., Limonium virgatum (Willd.) Fourr. and Tamarix smyrnensis Bunge ( Davis, 1965 ; Davis et al., 1988 ; Güner et al., 2000 ) ( Figures 4A–D ).

FIGURE 4 . (A‐D) Some scenery of Mersin.

Some plants of Mersin are endemic to Turkey; such as Alkanna hispida Hub.-Mor., Anthemis rosea Sm. subsp. carnea (Boiss.) Grierson ( Figure 5 ), Astragalus schottianus Boiss., Centaurea pinetorum Hub.-Mor. ( Figure 6 ), Colchicum balansae Planch., Crocus boissieri Maw, Delphinium dasystachyon Boiss. and Balansa, Eryngium polycephalum Hausskn. ex H. Wolff, Ferulago pauciradiata Boiss. and Heldr., Lamium eriocephalum Benth., Ophrys cilicica Schltr., Origanum boissieri Ietsw., Papaver pilosum Sibth. and Sm. subsp. glabrisepalum Kadereit, Pimpinella isaurica V.A.Matthews subsp. isaurica , Salvia heldreichiana Boiss. ex Benth., and Sideritis cilicica Boiss. and Balansa ( Davis, 1965 ; Davis et al., 1988 ; Güner et al., 2000 ).

FIGURE 5 . Habit view of endemic Anthemis rosea subsp. carnea .

FIGURE 6 . Habit view of endemic Centaurea pinetorum .

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

As mentioned above, Mersin is one of the most populous provinces of Turkey with a population density of 114.45/km 2 . Due to the migration mobility in the region, 55,779 people moved into and 61,917 people left the city center between 2017–2018. Regarding the population growth rate, there was a notable population increase in districts close to the city center. The number of men and women living in the province is almost equal, more than half of the population are under the age of 35, 38% are 35–64 and 9% of the population are over 65. The literacy rate is 97.72 ( TUIK, 2020 ).

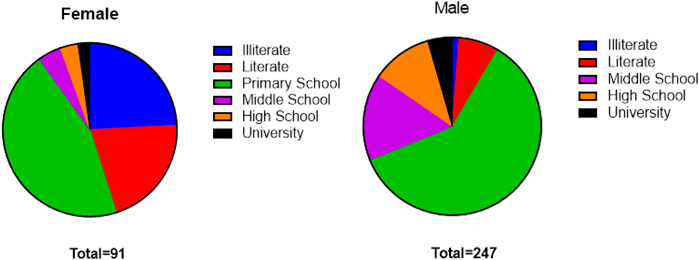

The villages of Mersin province have different characteristics depending on local geographical features, such as whether they are located at high or low (near the coast) altitudes, or are near to or far from the city. There are also migrant villages and a few semi-nomadic families living in the highlands. Most of the villages in Mersin are Yoruk, alongside villages consisting of Tahtacı, Cretan and Circassian peoples. As all of the participants spoke Turkish (some elderly participants could speak Cretan and Circassian languages in addition to Turkish), we did not experience language or communication problems. Most of the remaining population of these villages is elderly. Although many of them were literate, most were at the level of primary school education.

Data Collection

This study was conducted following the guidelines for best practices in ethnopharmacological research ( Heinrich et al., 2018 ). Ethnobotanical data were collected in face-to-face interviews ( Appendix 1 ) conducted in Turkish with inhabitants of Mersin on several trips to the province between 2018 and 2019. Field work was carried out over a total of 71 days. Plant vouchers were collected in collaboration with the informants. We adhered to The International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics in interviews ( International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics with 2008 additions http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ ).

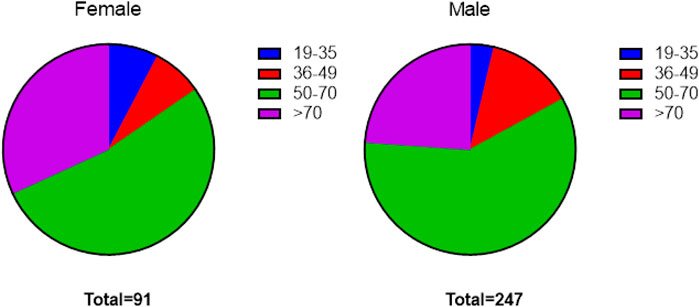

A total of 338 interviews were performed. Of the participants, 247 were male and 91 were female.

The informants’ occupations were farmers, housewives, shepherds, mukhtar (village headmen), labourers (forestry workers) and cafe owners. Interviews were performed in various settings, such as coffee houses, gardens, houses and fields. Experienced adults, patients and local healers were the main source of information about local names, part(s) of plants used, ailments treated, therapeutic effects, methods of preparation and methods of administration. Interviews also covered adverse effects of folk medicines. Although the primary focus of our study was to collect information on the folkloric use of medicinal plants, animal-based remedies were also discussed and recorded.

Collected plants were identified according to “The Flora of Turkey and East Aegean Islands” ( Davis, 1965 ; Davis et al., 1988 ; Guner et al., 2000 ) and “Illustrated Flora of Turkey Vol 2” ( Güner et al., 2018 ). Voucher specimens were deposited at the Herbarium of the Faculty of Pharmacy at Marmara University (MARE) and Herbarium of Konya at Selçuk University (KNYA).

Data Analyses

Informant consensus factor ( Trotter and Logan, 1986 ; Heinrich et al., 1988 ) was calculated according to the following formula: FIC =Nur–Nt/Nur-1 , where Nur refers to the number of citations used in each category and Nt to the number of species used. This method demonstrates the homogeneity of the information: if plants are chosen randomly or if informants do not contribute information about their use, FIC values will be close to zero. If there is a well-defined selection criterion in the community and/or if information is given between the informants’ values, the value will be close to one ( Afifi and Abu-Irmaileh, 2000 ; Abu-Irmaileh and Afifi, 2003 ). Medicinal plants with higher FIC values are considered to be more likely to be effective in treating a certain disease ( Teklehaymanot and Giday, 2007 ).

A quantitative method called “use value” (UV s ), calculated according to the formula UVs (medicinal use value) parameter using the Phillips and Gentry, 1993 formula as modified and used by Thomas et al., 2009 :

in which UV s is the use value of a given species s, U is is the number of uses of species s listed by the informant i, and ns is the total number of informants.

We used the most common method of dendogram clustering to demonstrate the relationship of the taxa and traditional usages in ten different districts of Mersin. The Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) was used for statistical analysis with v2. ( Sokal and Michener, 1958 ; Bailey, 1994 ).

The proportion and pairwise-proportion (with Holm adjustment) tests were used to compare the true (population) proportions. These tests were performed in R and the significance level was fixed at 0.05.

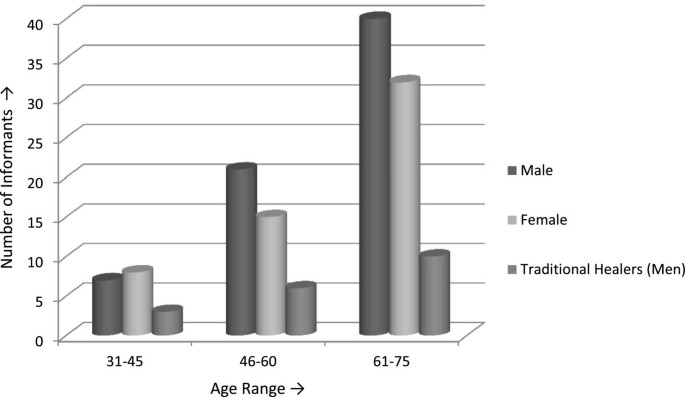

Demographic Features of the Informants

Details on the demographic characteristics of the participants were asked in face-to-face interviews. Among 338 participants, 16 were 19–35 years of age, 40 were 36–49, 194 were 50–70 and 88 were over the age of 70. The majority of the respondents were male (247) and 91 were female.

The age of the informants ranged between 19 and 91 years old with a mean age of 68 years.

Among all the participants; 25 were illiterate (7%), 37 were literate (11%), 190 had graduated from elementary school (57%), 43 from middle school (12%), 30 from high school (9%) and 13 from university (4%) ( Figures 7A,B , 8A,B ).

FIGURE 7 . Age groups of participants.

FIGURE 8 . (A–B) Educational status of participants.

The occupational groups of the participants consist of farming, animal husbandry, beekeeping, shepherding, retired, tradesmen and housewives. We gained access to four local healers, who can be regarded as practitioners of traditional medicine, for this study.

It should be noted that the reason women informants constituted only one third of the total number is that the study started mostly in the coffeehouses, which were generally in the center of the villages and in Turkey are frequented only by men.

Medicinal Plants and Related Knowledge

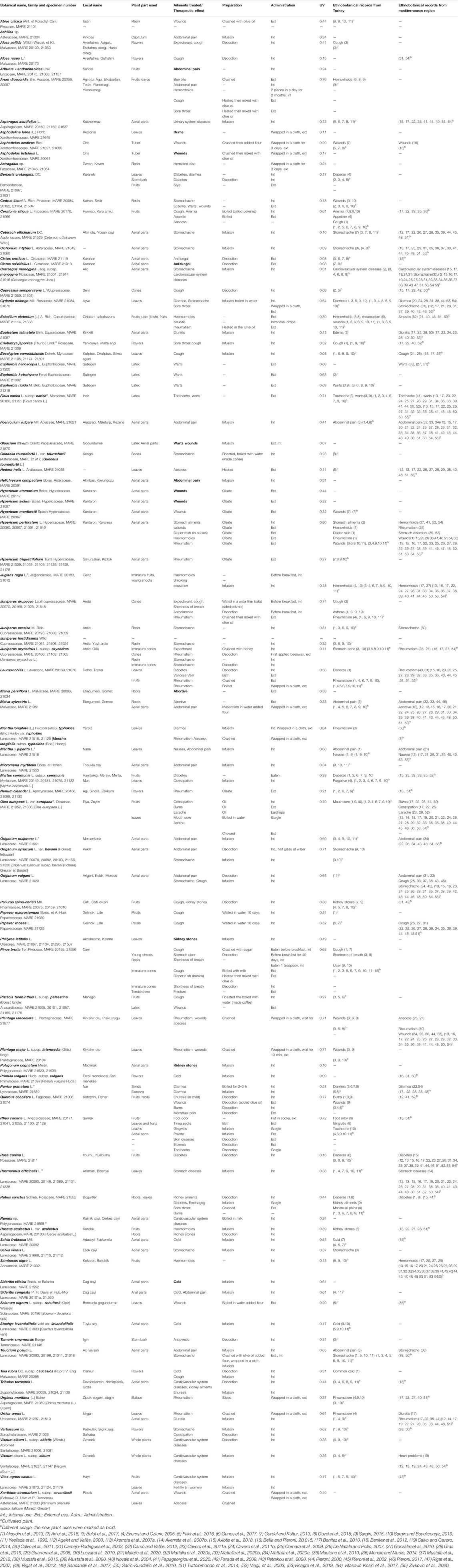

The plants used for medicinal treatment of human beings in Mersin are listed in Table 1 , while Table 2 shows the plants that see veterinary use. Both are arranged alphabetically by botanical name and include relevant information. Taxonomic changes according to The Plant List ( The Plant List, 2013 ) are shown in parentheses with scientific names in Table 1 . In total, 324 plant specimens were collected in the research area during the study period. Among these, 93 medicinal plants belonging to 43 families were identified; of these 83 taxa were wild and 10 were cultivated. The most commonly used medicinal plants were in the Lamiaceae (14 taxa), Rosaceae (5 taxa), Malvaceae (5 taxa), Hypericaceae (5 taxa), Asteraceae (5 taxa) and Cupressaceae (5 taxa) families.

TABLE 1 . Folk medicinal plants of Mersin (Turkey).

TABLE 2 . The plants used in veterinary medicine in Mersin (Turkey).

The UV data is summarized in the statistical data analysis section. Amongst the most commonly used plants were Hypericum species. During our interviews, participants shared that they learned about using the oleate of Hypericum species for external wound treatment from their ancestors, emphasizing that it was even used for sword wounds in ancient times. We even observed that many of the participants’ kept this oleate in their homes.

The fruit of Arum dioscoridis Sm, is the leading herb used in the treatment of haemorrhoids in the region. The leaves are boiled and consumed as food while fruits are used as toys.

We recorded that the latex of Euphorbia helioscopia L., E. kotschyana Fenzl , E. rigida M. Bieb. , Glaucium flavum Crantz and Ficus carica L. are used for the treatment of warts in the region. F. carica latex is also used for toothaches.

Molasses “pekmez” prepared from the fruits of C. siliqua and J. drupaceae , which are very common in the flora of the region, was traditional product used in children and adults, especially in upper respiratory tract diseases, and was also sold in the local markets.

Female participants over 60 years of age, who contributed to our research in the region, mentioned that the roots of Malva species were previously used to terminate pregnancies when birth control methods were not common, and that their mothers frequently applied this method.

Helichrysum compactum Boiss., S. cilicica and S. congesta P. H. Davis et Hub.-Mor. are endemic species of the region with therapeutic usages (presented in Table 1 ). S. cilicica and S. congesta were the most consumed herbal teas in the region and are cultivated in the gardens of some participants.

Gundelia tournefortii L. var , tournefortii and Pistacia terebinthus L. subsp. palaestina (Boiss.) Engler were used to prepare a special traditional coffee. In addition, fruits of P. terebinthus were used as a snack and sold in local bazaars.

M.communis is used in treatments for diabetes and constipation , and its fruits are also consumed as a snack. Another application we recorded in almost every village in our study was its usage during cemetery visits.

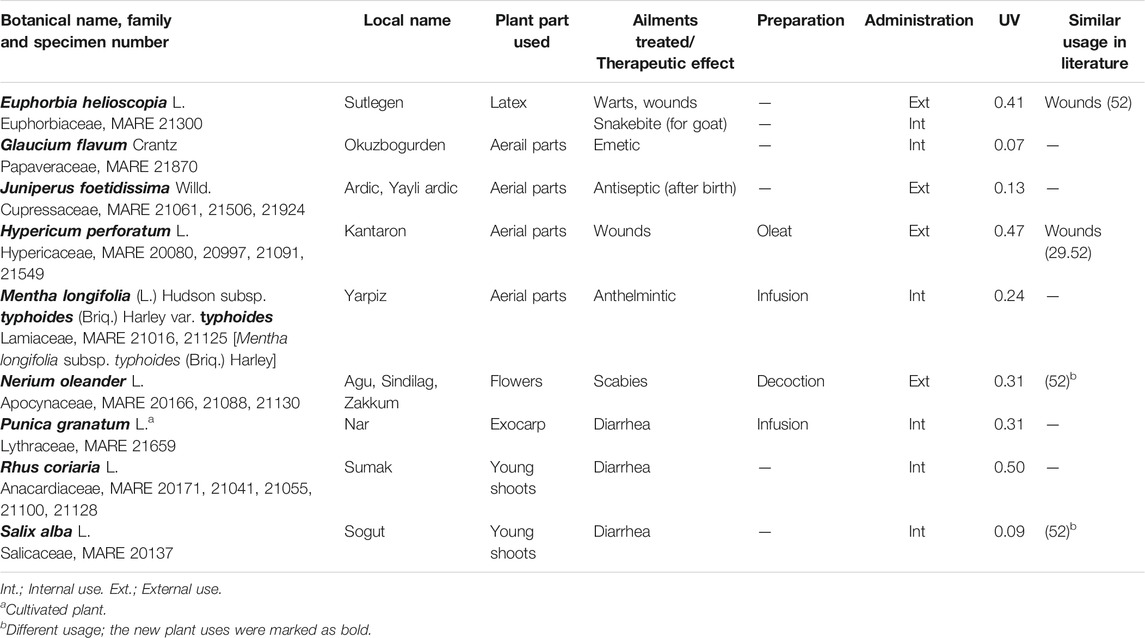

Euphorbia helioscopia L., Glaucium flavum Crantz, J. foetidissima , H. perforatum , N. oleander , Mentha longifolia (L.) Hudson subsp. typhoides (Briq.) Harley var. typhoides , Punica granatum L. and Rhus coriaria L. are used in the treatment of both humans and animals. Among the medicinal plants used for veterinary purposes, we found that only Salix alba L. is used exclusively for the treatment of animals ( Table 2 ).

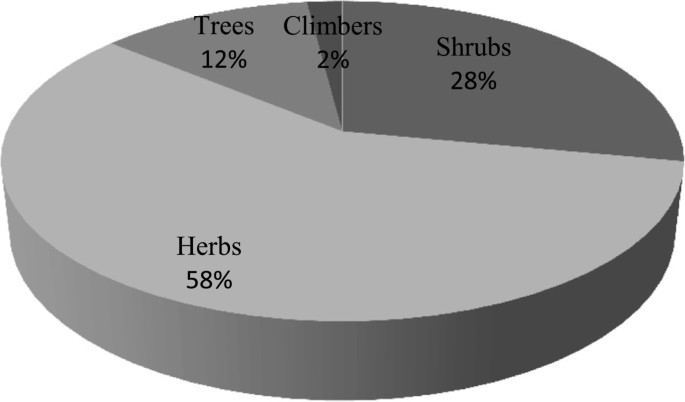

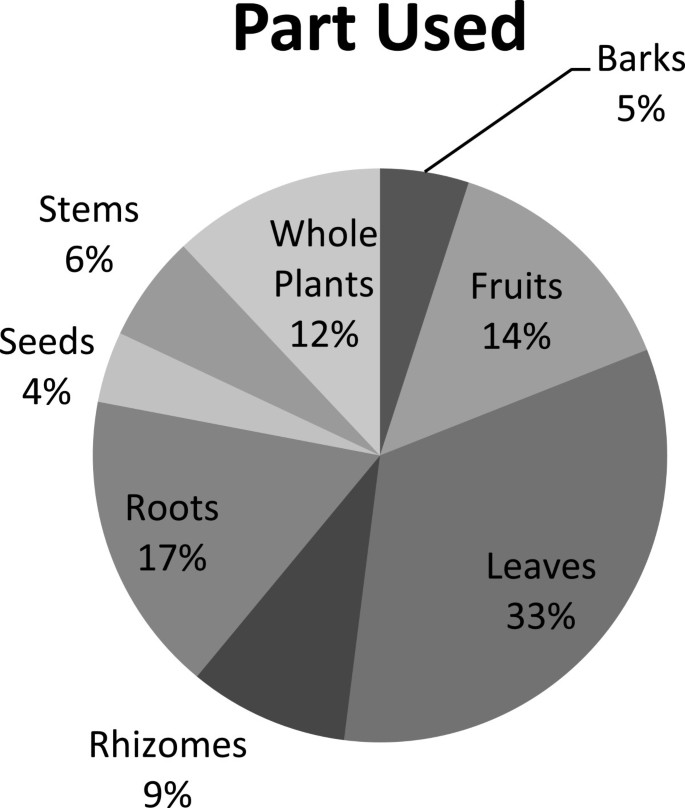

Plant Parts Used and Methods of Preparation

The parts of plants used for medicinal purposes were aerial parts (26.8%), leaves (18.4%), fruits (15.1%) and flowers (7%). The main preparation methods using these parts were infusion (27.6%), direct application (22.2% without any preparation procedure), decoction (18.9%), application after crushing (11.4%), and other less common methods (19.9%).

A total of 189 drugs were recorded in this study. Most were used internally (55.7%) ( Table 1 , Table 2 ). Olive oil, flour, honey and sugar were used as additional ingredients in the preparation of these remedies.

The medicinal plants used in multiherbal recipes containing two or more species are presented in Table 3 . A decoction prepared from R. coriaria and Q. coccifera is used in the treatment of warts and a mixture prepared from P. brutia and H. perforatum is used in stomach disorders.

TABLE 3 . Multiherbal recipes used as folk medicine in Mersin.

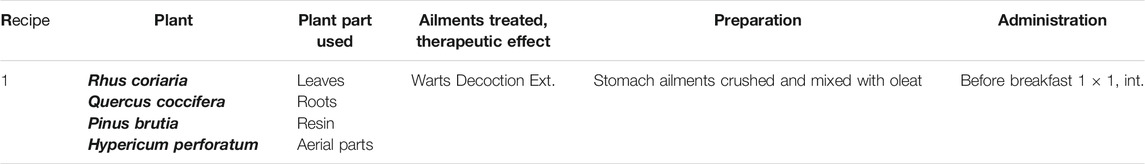

Plant Names

Local names of medicinal plants are also recorded in this study. The names of the all plants in Turkish, as well as some Cretan plant names, were recorded during the study. Some of these plants have vernacular names that are also used for different plant species, potentially leading to complications. These are presented in Table 4 , where we see that in some cases different species of the same genus have the same common names.

TABLE 4 . The same vernacular name was used for more than one plant species.

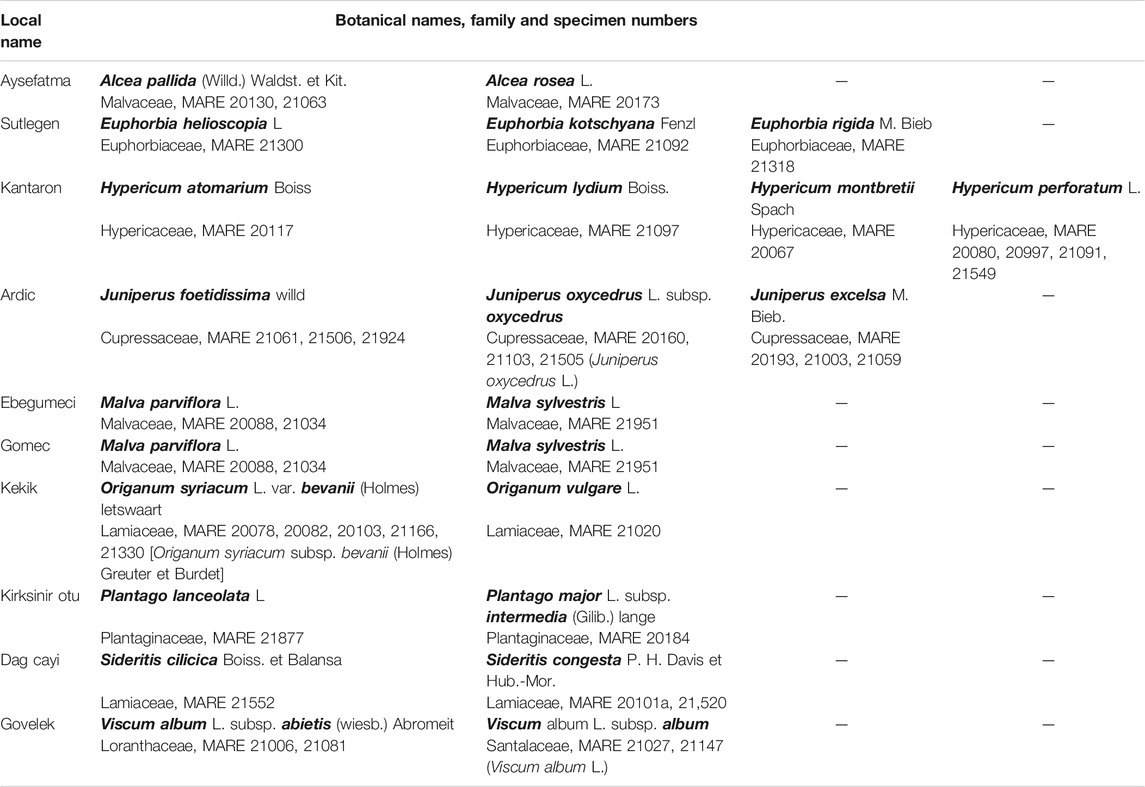

Statistical Data Analysis

Analysis of the diversity and similarity among districts, based on the ten districts, using species abundance and amount of information on treatment usage, was carried out by hierarchical clustering ( Figure 9 ). The analysis resulted in five main clusters at the truncation point of 20. Erdemli, Mut, Gulnar and Silifke, which are close to one another, showed greater similarity among themselves. Similarly, Aydincik and Bozyazi, which are proximate to one another, also displayed very similar characteristics. Interestingly, there was a close similarity between Anamur and Camliyayla, despite them being far apart. Merkez and Tarsus were both different from the other districts, but Tarsus was the most distinct among the districts.

FIGURE 9 . Dendogram showing UPGMA clustering (with Euclide distance) of districts (those where over 10 interviews were carried out).

The proportion test was used to compare the true (population) proportion of the population who recognize and use these species in the various districts. The proportions are given below: 1-Camliyayla (0.72), 2-Tarsus (0.82), 3-Merkez (0.88), 4-Mut (0.66), 5-Anamur (0.60), 6-Silifke (0.91), 7-Gülnar (0.92) and 8-Erdemli (0.86). Bozyazı and Aydıncık districts wasn’t included.

The p -value was 0.0005773 < 0.05. We conclude that there is a significant difference between the districts in terms of awareness of the species. The pairwise comparison with Holm adjustment was conducted to detect the differences between the districts. The difference between 5–3 ( p value = 0.044) and 5–6 ( p value = 0.042) are significant. This result indicates that the major source of difference was the district (Anamur). We can interpret this to mean that Anamur uses fewer species in the traditional treatments than the other districts.

The proportion test was also used to compare the true (population) UV index for the species. As a result of our analysis, the plants with the highest UV values are H. perforatum (0.80), C. libani (0.78), Q. coccifera (0.77), Arum dioscoridis (0.76) and J. drupaceae (0.74), which are presented in Table 1 .

After analysis, the p -value is obtained as 0.4423 > 0.05. It is concluded that there is no significant difference between the five most commonly used species in terms of UV.

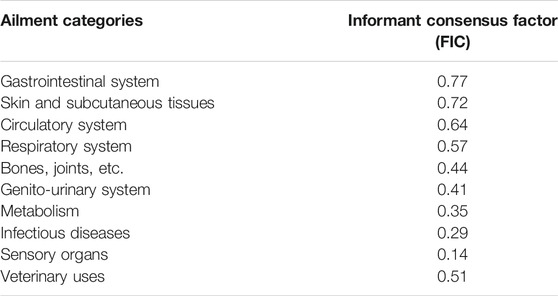

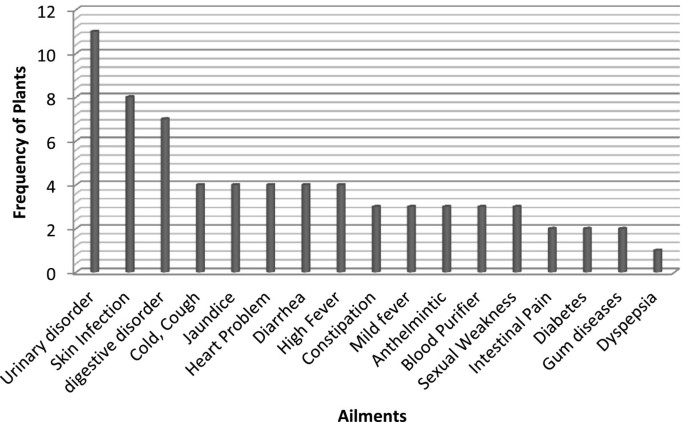

According to the FIC results, gastrointestinal system diseases (mainly stomach ailments) had the highest value at 0.77, followed by skin and subcutaneous tissues (mainly wound healing) at 0.72, circulatory system (mainly haemorrhoids) at 0.60, respiratory system (mainly cold) at 0.57, urinary/genital system (0.41), musculo-skeletal (mainly rheumatism, 0.44) and finally metabolism (mainly diabetes, 0.35) disorders ( Table 5 ).

TABLE 5 . FIC values of category of ailments.

Folk Remedies and Related Knowledge Originating From Animals

This research determines that some animals, which constitute an important part of biological diversity, are used for medical purposes in addition to plants used as traditional folk medicine in Mersin. Because animal-based folk remedies are a part of traditional therapy, we present them in this study alongside plants. The folk remedies derived from animals ( n = 110) recorded during fieldwork via interviews with informants are presented in Table 6 .

TABLE 6 . Animal-based folk remedies used in Mersin for treating human diseases.

We observed that local people dealing with animal husbandry and hunting as a hobby in the area reaching from villages near the coast to the slopes of the Taurus Mountains were more knowledgeable in this regard.

We found that the use of hedgehog meat for haemorrhoid treatment is very common in the region. The participants added that it is very tasty alongside its therapeutic properties. In addition to the use of animals or animal products for human health, it is very common to use tortoize shell against the evil eye, especially among Yoruks. Furthermore, women and young girls of the village were said to knit with hair from the tails of horses when they could not find thread in Camliyayla, where needle lace is a common traditional handicraft. For this reason, the owners of white horses have to keep their horses tied up in their barns.

We were also informed that the calabash ( Lagenaria sp.), known as “Kaplankabak” in the Gülnar area, is used as an instrument to make sound that keeps predators away to protect people living in tents. A piece of tanned goat skin is stretched across the calabash and a rope is inserted into a hole in the skin. An intense noise is produced when the rope is pulled ( Supplementary Video S1 ).

Comparison With Previous Studies

Comprehensive ethnobotanical studies previously carried out in neighboring areas ( Yeşilada et al., 1993 ; Everest and Ozturk, 2005 ; Akaydın et al., 2013 ; Arı et al., 2018; Gürdal and Kültür, 2013 ; Güzel et al., 2015 ; Sargin, 2015 ; Fakir et al., 2016 ; Bulut et al., 2017 ; Güneş et al., 2017 ; Sargin and Büyükcengiz, 2019 ) found that P. brutia was the most commonly used herbal medicinal plant at ten localities in Mersin and its environs. Our findings compared with previous studies can be seen in Table 1 , Table 2 .

In previous studies, widely distributed species A. cilicica, C. libani, C. siliqua, H. perforatum, J. drupaceae, J. oxycedrus, L. nobilis, M. communis and O. syriacum subsp. bevanii were found to be the major plants used in traditional folk medicines. The most commonly used method for preparation in Mersin is infusion ( Akaydın et al., 2013 ; Sargin, 2015 ; Sargın et al., 2015 ; Sargin and Büyükcengiz, 2019 ).

Sargın et al., 2015 ; Sargin, 2015 ; Sargin and Büyükcengiz, 2019 noted that the fruits of C. siliqua and J. drupaceae in particular were used for “molasses” in the region. In addition, L. nobilis, locally known as “teynel,” is commonly used for medicinal purposes. Its leaves are used as a spice and during summer in the process of drying fruits to be eaten in winter. The plant is also commonly used in herbal soaps and sold in local markets. Our results agree with these previous findings.